-

磷作为植物生长及发育必需大量营养元素,通常以无机磷肥形式施用于土壤[1]。无机磷肥进入土壤后,极易被土壤固相吸附或与钙镁等金属阳离子形成难溶性络合物,导致其植物可利用性降低。此外,20%—80%磷肥转化为有机磷,占土壤全磷的40%—90%,仅约0.1%可被植物直接吸收利用[2]。因此,为保障农作物营养和产量,常施用过量磷肥,造成严重且广泛的环境污染问题[3]。磷肥的大量施用导致土壤酸化和植物营养失衡,且易在土壤中富集,造成土壤磷污染,并通过地表/地下水进入到水体中,引起水体的富营养化[4]。据此,提高土壤有机磷的植物利用率可优化农作物生产、降低磷肥施用量、降低磷流失及水体污染风险。

矿化作用是在土壤微生物作用下,土壤中有机态化合物转化为无机态化合物的总称。植酸(肌醇六磷酸)是土壤有机磷的主要存在形态(50%—70%)[5]。然而,植物根系难以直接吸收植酸,通常植酸需被专一性酶(植酸酶)水解生成植物能够吸收利用的正磷酸盐(磷酸氢根、磷酸二氢根)[6]。植酸酶(肌醇六磷酸水解酶)属于一类特殊的酸性磷酸单酯水解酶,能有效催化植酸及其盐类水解并产生肌醇衍生物和磷酸盐,可由土壤微生物分泌至植物根际环境中发挥作用[7]。植酸酶基因(phyA)由Richardson等[8]在黑曲霉(Aspergillus niger)中发现,并将其转入拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliaha),转基因拟南芥相较于野生型拟南芥的植酸酶活性由3.9—14.3 U·mg−1提高至224—14980 U·mg−1,其生长和磷营养得到显著改善,表明转基因植物可通过表达微生物植酸酶基因,高效分泌植酸酶进而有效利用植酸。Nelson等[9]首次证实饲料中的植酸可经过微生物植酸酶水解,释放出磷元素,极大推动微生物植酸酶的研究进展。随后一系列关于植酸酶提高植酸磷生物利用率的研究证实,微生物植酸酶基因可以显著促进植酸酶分泌,进而提高基质中植酸的分解效率,可为植物提供充足的磷营养[10]。因此,微生物是驱使土壤植酸矿化的关键因子,可高效分解难利用态有机磷,补偿植物根际有效/活性磷,是植物生长的重要磷源[11]。

近年来,伴随着对微生物植酸酶的研究逐步深入,关于其在农业领域的应用已引起广泛关注。目前,研究多集中于各类微生物植酸酶对谷类作物植酸矿化和在家禽动物营养中的作用,关于其对土壤植酸矿化与土壤有机磷利用的系统性综述报道较少。由此,本文主要关注微生物植酸酶对土壤植酸的矿化作用,重点阐述其过程、机制和效率,包括微生物植酸酶的种类来源、酶学性质、作用机理和实际应用等方面的研究进展。该综述可为提高土壤有机磷的生物利用率、减少农业磷肥施用、降低土壤磷流失及水体污染风险提供理论依据和技术支撑,为深入探究植酸酶功能并应用于农业生产实践及保障生态环境安全提供参考。

-

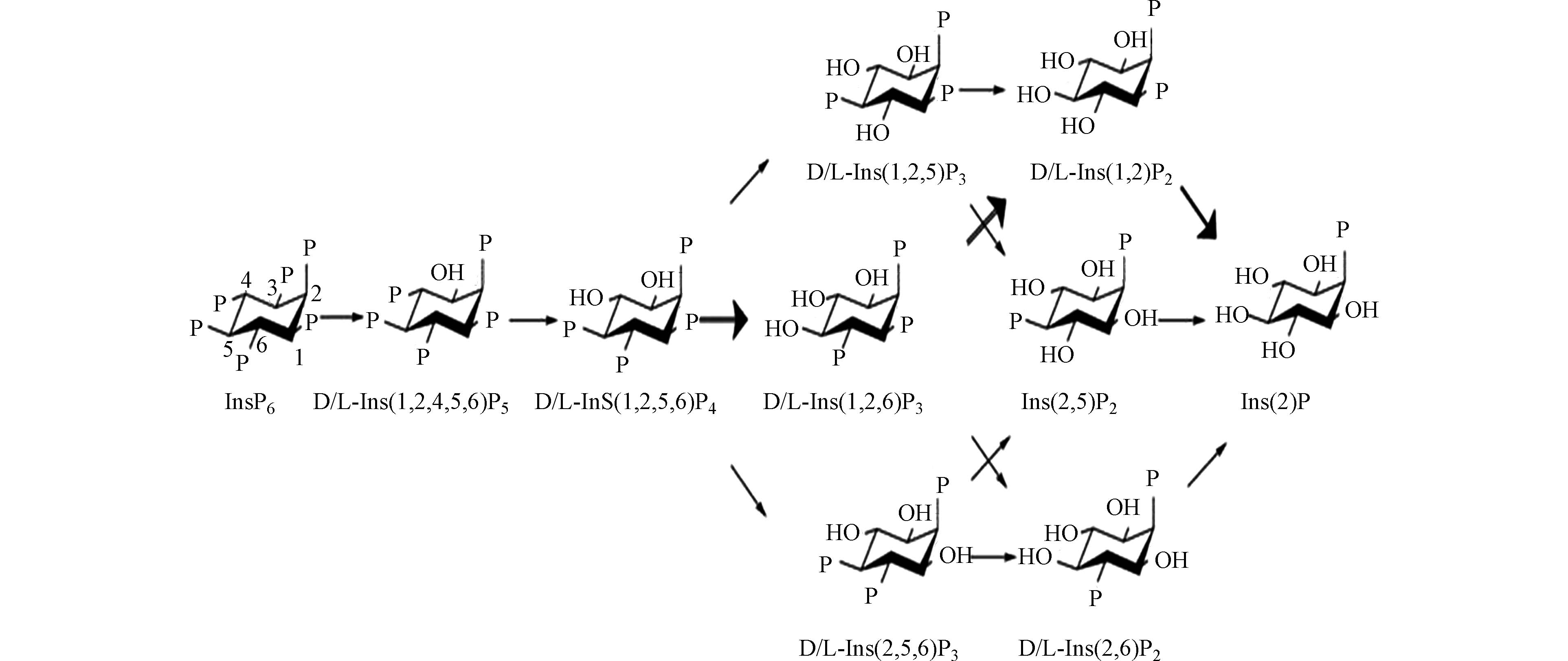

植酸是一种有机磷化合物,属维生素B族的一类环己六醇磷酸酯,为饱和环状酸,易溶于水、甘油和丙二醇等,不溶于苯、氯仿和乙烷等。植酸的分子式是C6H18O24P6,分子量660,化学名称为环已六醇–1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6–六磷酸二氢酯,其化学构造由1分子肌醇和6分子磷酸结合而形成,即肌醇的6个碳原子上羟基均被磷酸酯化生成的肌醇衍生物(图1A)[12]。在植物中植酸主要存在于种子里,其中以豆科、谷物、油籽和坚果作物种子的含量最丰富,其含量达1%—3%,占植物体内总磷含量的40%—90%,是植物种子/谷类作物中肌醇和磷酸的重要储备库[13]。

植酸的结构稳定,高温(>120 ℃)可分解,其中6个磷酸基团拥有比较强的螯合能力,可与金属阳离子(如Ca2+、Mg2+、Cu2+、Zn2+、Fe3+等)形成极稳定的螯合物,降低营养元素的生物有效性,降低植物和家禽等动物对矿质元素的吸收,因而被称为抗营养因子[14]。此外,植酸可与蛋白质进行络合反应,其作用形式与蛋白质的等电点有关,比蛋白质等电点低时,植酸和蛋白质分子上的碱性基团发生反应,形成很稳定的蛋白质络合物,影响动物体内的蛋白酶活性(如胃蛋白酶、胰蛋白酶和淀粉蛋白酶等);较蛋白质等电点高时,植酸通过Ca2+、Mg2+等金属阳离子连接形成“植酸–金属离子–蛋白质”复合物,同样可以降低蛋白酶活性[15]。植酸的络合能力与乙二胺四乙酸(EDTA)相似,但因其独特性质(稳定护色、抗氧化性、耐腐蚀性等),相较于EDTA应用更为广泛,主要应用于食品工业中作为果蔬及水产的护色剂和保鲜剂、医药领域中作为止渴剂、生物学领域中作为发酵促进剂促进微生物代谢、金属加工领域中作为防锈剂和防蚀剂等[16]。

-

植酸酶,属磷酸单酯水解酶,能催化植酸及其盐类水解为肌醇和磷酸盐,具有特殊空间结构(图1A),可使植酸脱磷酸化,并释放无机磷酸盐[17]。植酸酶主要存在于微生物以及动植物中,由于微生物分布的广泛性及其植酸酶具有易分离提纯、稳定性强、活性高等动植物植酸酶不具备的特点,目前对微生物(细菌、真菌、酵母菌等)植酸酶的研究最为广泛[18]。

-

美国国立生物技术信息中心(national center for biotechnology information, NCBI)的蛋白质数据库里细菌植酸酶数量远多于真菌植酸酶。目前已报道的产植酸酶细菌主要包括淀粉乳杆菌(Lactobacillus amylovorus)、大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)、肠杆菌(Enterobacter sp.)、枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis)、地衣芽孢杆菌(Bacillus licheniformis)、解淀粉芽孢杆菌(Bacillus amyloliquefaciens)、克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella sp.)、假单胞菌(Pseudomonas sp.)、反刍月形单胞菌(Selenomonas ruminantium)、链球菌(Streptococcus sp.)、嗜酸乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus acidophilus)和干酪乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus casei)等。细菌植酸酶具有较高的热稳定性(如芽孢杆菌(Bacillus sp.)植酸酶)—70 ℃温浴10 min后仍具有100%的酶活性,以及高蛋白水解稳定性(如大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)植酸酶)—植酸酶蛋白质浓度可达菌体总蛋白的47%,在植酸水解和有机磷利用等方面有着良好应用前景[19]。例如,表达植酸酶基因的大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)具有繁殖快、表达量高、成本低的特点[20]。但糖基化是细菌表达载体生产植酸酶的主要问题,由于蛋白质产物在大量表达时极易产生错误的折叠致使酶活性丧失,因此糖基化的不同程度对于细菌植酸酶的热稳定性有着重要影响[13]。

在微生物中,真菌植酸酶的活性最强,而且真菌植酸酶通常为便于分离纯化的胞外酶,所以真菌多用于工业化生产植酸酶[21]。产植酸酶真菌主要包括无花果曲霉(Aspergillus ficuum)、土曲霉(Aspergillus terreus)、米曲霉(Aspergillus oryzae)、烟曲霉(Aspergillus fumigatus)、黑曲霉(Aspergillus niger)、青霉菌(Penicillium)等[22]。研究已证明黑曲霉(Aspergillus niger)植酸酶活性较高,其植酸酶基因phyA已在多种真菌中成功表达,而其他真菌植酸酶活性较低,且曲霉(Aspergillus sp.)植酸酶生产安全性较好,因此是目前工业化生产应用较多的真菌[23]。

酵母菌的致病性比较低,是植酸酶产生菌理想的研究对象,但当前对酵母菌植酸酶的研究较少,尚缺少工业化生产。已知主要的产植酸酶酵母菌分别有热带假丝酵母(Candida tropicalis)、毕赤酵母(Pichia pastoris)、酿酒酵母(Saccharomyces cerevisiae)等[24]。在众多产植酸酶的酵母菌中,斯巴达克毕赤酵母(Pichia spartinae)植酸酶的活性最高[25]。酵母菌的遗传信息较为全面,而且便于操作,来自细菌和真菌的异源植酸酶基因已在酵母菌中成功表达,由于外源蛋白表达时容易出现过度糖基化,阻碍合成蛋白的分泌和运输,故目前可作为表达载体的酵母菌种类较少,主要为毕赤酵母(Pichia pastoris)[26]。

-

为分离具有胞外植酸酶活性的细菌、真菌和酵母菌,已开展较多关于产植酸酶微生物筛选的研究。Richardson和Hadobas[27]使用含植酸钠的筛选培养基,从土壤中分离出238种产植酸酶细菌,其中,4株假单胞菌(Pseudomonas spp.)植酸酶活性较高,分别是荧光假单胞菌(fluorescent Pseudomonas)—恶臭假单胞菌(Pseudomonas putida)CCAR53和CCAR59、非荧光假单胞菌(nonfluorescent Pseudomonas)—门多萨假单胞菌(Pseudomonas mendocina)CCAR31和CCAR60,其植酸酶活性分别是13.4×10−3、13.3×10−3、7.3×10−3、6.9×10−3 U·mg−1,分别从植酸钠释放出57%和54%无机磷。1994年,Volfová等[28]筛选得到132种产植酸酶微生物,其中胞外活性植酸酶主要来自真菌。随后,Gargova等[29]通过两步筛选(合成植酸酶琼脂培养基初步筛选和玉米淀粉液体培养基二次筛选)得到203种产植酸酶真菌。Lambrechts等[30]首次发现酵母菌Schwanniomyces castellii分泌物具有极高的植酸酶活性(237 U·mg−1),是其他菌株植酸酶活性的2.8倍。Sano等[31]筛选得到约1200株酵母菌株,以植酸作为唯一磷源进行培养,发现除酵母白囊杆菌(Arxula adeninivorans)外,大多数微生物无法生长,表明该微生物具有分泌植酸酶和降解植酸的能力。

Bae等[32]建立了一种定性分析微生物植酸酶活性的方法,即用特异性琼脂培养基中沉淀态植酸钙/植酸钠的减少作为具有酶活指示。Engelen等[33]建立了简便快捷的定量分析微生物植酸酶活性的方法,即测定pH 5.5时,植酸钠分解释放无机磷含量。然而,仍有大量的产植酸酶微生物有待鉴定。目前,通过NCBI的蛋白质数据库和基因组数据库中同源序列鉴定,发现许多可以在自然环境下分泌胞外植酸酶的微生物。

分离筛选的微生物可用液态深层发酵技术(submerged fermentation,SmF)及固态发酵技术(solid state fermentation,SSF)生产植酸酶[34]。其中,SmF作为主要的生产技术已被广泛使用,其特点是发酵的周期短、劳动的强度低与生产率高等,特别适用于细菌和酵母菌的植酸酶生产[35]。SSF是微生物在没有或基本没有游离水的固态基质上的发酵方法,近年来,作为“高产量低成本”的生产技术,SSF在微生物植酸酶生产方面表现出极大优势,如微生物易生长、酶活性高、酶系丰富,发酵过程中无需严格的无菌条件,设备构造及后续处理简单、且易操作、能耗低、投资少、污染小等[36]。真菌植酸酶生产可通过SmF或SSF[37]。培养条件、菌种类型、底物性质和养分有效性是影响微生物植酸酶产量的关键因素。Han等[38]采用半固体底物发酵的方式生产植酸酶,发现固态发酵产生植酸酶含量比液态发酵高2—20倍。Papagianni等[39]研究SmF和SSF中培养基组成、黑曲霉形态和植酸酶产量之间的相关性关系,发现培养基组成和真菌形态对SmF生产方式中植酸酶的产生影响较大,随后添加有机磷酸盐,均可促进SmF及SSF中黑曲霉生长与植酸酶产生,其植酸酶活性分别由6770 U·mg−1和162 U·mg−1提高至8090 U·mg−1和1800 U·mg−1。这些研究表明在选择特定生产技术时,应当考虑培养的条件、菌种的类型、底物的性质和养分有效性等重要因素的影响。

-

微生物植酸酶的种类繁多,其结构各不相同,催化机制也各有不同,目前各种微生物的植酸酶种类与酶学性质(最适温度/pH、分子量、米氏常数Km值、特异性酶活性)分别见表1、2。

依据植酸发生水解脱磷酸化的位置,微生物植酸酶可以分成3类:3–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.8)、6–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.26)及5–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.72),分别是在植酸的第3位、6位及2位碳原子上水解释放磷酸基因[27]。根据其来源,可分为3类:细菌植酸酶、真菌植酸酶、酵母菌植酸酶[103]。根据酶活最适pH,可分成酸性植酸酶(最适pH=5—6)和碱性植酸酶(最适pH=8—10),真菌及多数细菌分泌酸性植酸酶,少数细菌分泌中性(最适pH=7—7.5)或碱性植酸酶[104]。根据催化机制,可分为4类:组氨酸酸性磷酸酶(histidine acid phosphate,HAP),大多来源于肠杆菌(Enterobacter sp.)及真菌,当前应用较为普遍;β螺旋植酸酶(β–propeller phytase,BPP),多数来源于芽孢杆菌(Bacillus sp.),具有较强的稳定性;然而半胱氨酸植酸酶(cysteine phytase,CP),只发现存在于瘤胃微生物(rumen microbiome);紫色酸性磷酸酶(purple acid phosphate,PAP),在真菌以及细菌中分布广泛[52]。

植酸酶来源不相同,其最适pH差异亦较大[105]。细菌、真菌、酵母菌植酸酶最适pH分别为2.7—8.0、2.5—6.0、2.5—5.5,通常微生物植酸酶活性pH值是4.0–7.5,在当pH<3.0或>7.5时,其酶活性急剧下降至失活[106]。微生物植酸酶活性温度为50—70 ℃,细菌、真菌、酵母菌植酸酶最适温度为分别为37—75 ℃、40—70 ℃、40—77 ℃,45—60 ℃活性较为稳定,更高温度(>80 ℃)易失活[107]。

-

谷物饲料中含有大量植酸(盐),家畜难以直接消化利用,故植酸(盐)以未分解形式通过家畜排泄物进入土壤,此外,农业生产过程施用的大量无机磷肥可转化为植酸有机磷,造成土壤植酸积累[103]。微生物通过分泌植酸酶水解土壤植酸,释放无机磷供植物直接吸收(图1B)。Chen等[108]指出,土壤植酸矿化分解与植酸酶数量和活性具有显著相关性。Bünemann[109]指出,>60%土壤有机磷可被磷酸酶水解,其中植酸酶释放的磷高达80%。Tarafdar等[110]发现,微生物植酸酶能有效水解土壤植酸从而释放无机磷酸盐,比动植物植酸酶效率高约50%。以上研究表明,微生物是驱动土壤植酸矿化的关键因子,对提高土壤有机磷的利用率具有重要作用。

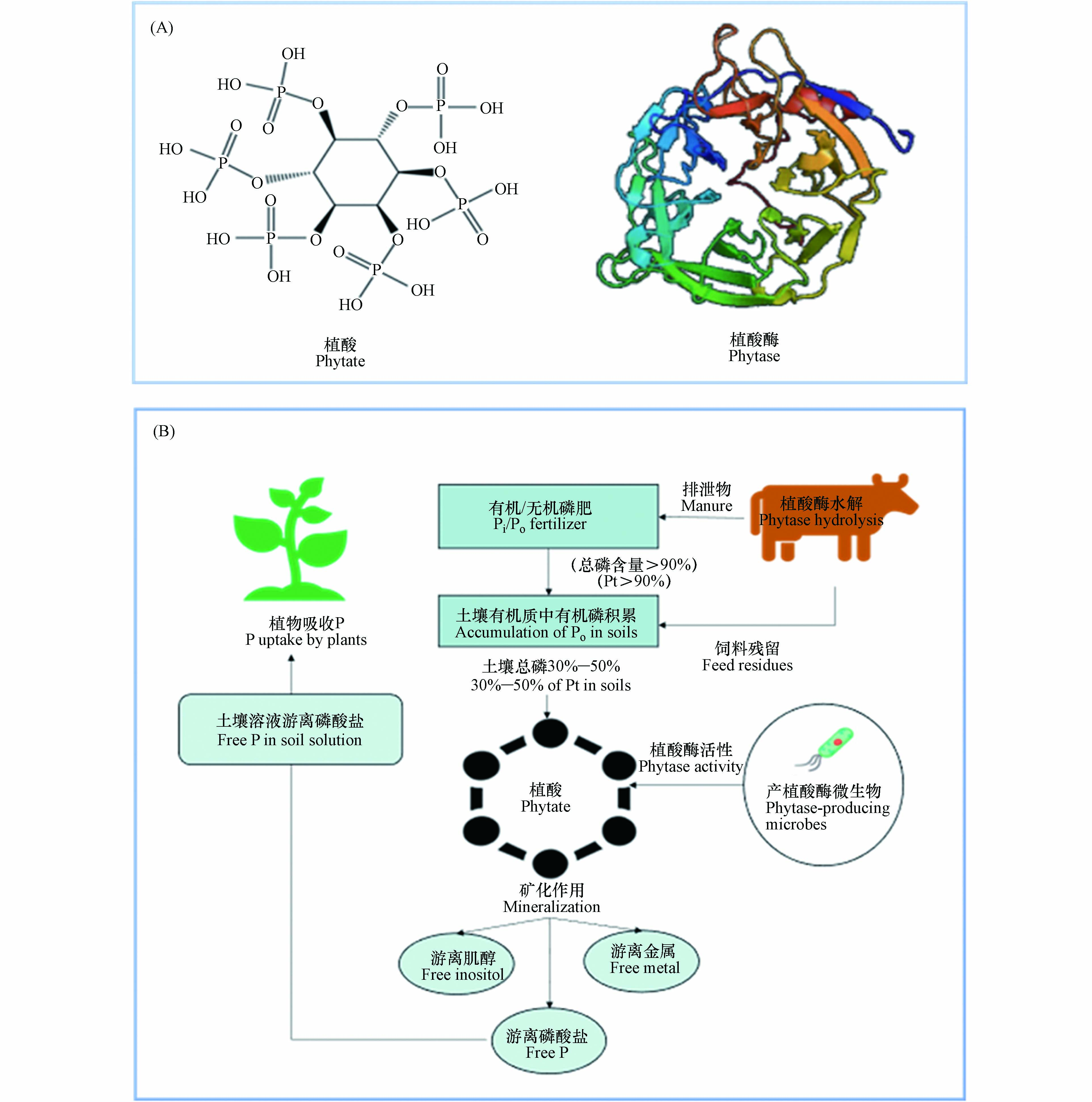

植酸的矿化机制虽在上世纪60年代已被研究,但当前植酸的代谢途径和形成产物仍然是植酸酶研究的重点。随着分离方法的发展,尤其是色谱技术在矿化产物分析中的广泛应用,发现不同来源植酸酶的作用机理存在差别[111],其中,微生物植酸酶矿化植酸的途径为:植酸→DL-1,2,4,5,6–五磷酸肌醇→DL-1,2,5,6-四磷酸肌醇→DL-1,2,5-三磷酸肌醇/DL-1,2,6-三磷酸肌醇/DL-2,5,6-三磷酸肌醇→DL-1,2-二磷酸肌醇/2,5-二磷酸肌醇/DL-2,6-二磷酸肌醇→2-磷酸肌醇(图2)[112]。

-

微生物植酸酶活性是植酸矿化效率的主要影响因子(表2),而微生物植酸酶活性受生物和物理化学过程的影响[113],前者引起酶生产速率、同工酶(催化相同反应而分子结构不同的酶)生产和微生物群落组成的变化,后者引起吸附解吸反应、底物扩散速率和酶降解速率的变化[114]。影响酶活性的关键因素包括:

(1)微生物植酸酶活性由底物种类和数量等几个相互关联的因素共同决定[115]。通常使用添加不同底物的方法来测定微生物的植酸酶活性,包括萘磷酸、6–磷酸葡萄糖、2–甘油磷酸、植酸钠、植酸钙、β–甘油磷酸盐、对硝基苯酚磷酸盐、6–磷酸果糖、一磷酸腺苷(adenosine–5’–monophosphate,AMP)、二磷酸腺苷(adenosine–5’–diphosphate,ADP)、三磷酸腺苷(adenosine–5’–triphosphate,ATP)、三磷酸鸟苷(guanosine–5’–triphosphate,GTP)和烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸(nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate,NADP)等[116]。根据底物的差异,将其分成特异性及非特异性酸性磷酸酶[117]。研究发现,一些微生物植酸酶对植酸具高特异性,如芽孢杆菌(Bacillus sp.)、曲霉菌(Aspergillus sp.)和大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)[118],其中枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis)植酸酶活性随植酸浓度增加而增加,最高活性可达10 mmol[119]。

(2)反应体系的pH对微生物植酸酶活性具有一定影响。微生物植酸酶比植物植酸酶具有更宽泛的pH适宜范围,但其最适pH因微生物种类而存在差异[30]。植酸酶主要分成碱性植酸酶以及酸性植酸酶,其最适pH值范围是5.0–8.0[59]。真菌植酸酶的最适pH值为4.5–6.5,如烟曲霉(Aspergillus fumigatus)[120]。丝核菌(Rhizoctonia sp.)和镰刀菌(Fusarium verticillioides)在pH分别为4.0和5.0时分泌植酸酶[121]。而细菌植酸酶在pH值分别为6.0和8.0时活性最强,如芽孢杆菌(Bacillus sp.)[62]。因此,控制适宜反应体系的pH值对保障微生物植酸酶的产量及其活性有利。

(3)温度是微生物植酸酶活性的重要影响因素,既影响微生物活性(即植酸酶的生成与产量),亦影响酶的活性(即植酸矿化速率)[122]。一般通过计算活化能(Ea)来确定酶对温度的响应,两个过程(生产和降解)的速率本应随着温度的升高而增加,但由于Ea的差异,它们表现出不同的温度敏感性[123]。研究表明,微生物植酸酶的温度敏感性随季节变化,并且在单一环境中存在差异[124]。与温暖气候相比,微生物在寒冷气候中分泌植酸酶的最适温度较低、结构灵活性和改变结构的能力较差[125]。微生物植酸酶的最适温度范围为35—77 ℃,镰刀菌(Fusarium verticillioides)植酸酶最适温度为50 ℃,其稳定性可保持至60 ℃,而克雷伯菌属(Klebsiella sp.)植酸酶在较低温度37 ℃保持最大活性[126]。Johnson等[127]研究指出,产植酸酶微生物的代谢速率随温度升高而加快,平均Ea为0.62 eV。因此,与酶动力学本身相比,温度对微生物植酸酶的代谢速率起着更为重要的作用。

(4)土壤理化性质的影响,包括全氮含量和土壤质地类型[128]。氮是微生物植酸酶生产中不可缺少的元素,对不同氮源影响微生物植酸酶产量的研究发现,在麦麸培养基和桔皮粉培养基中添加0.1%磷酸二氢铵(NH4H2PO4)时微生物植酸酶产量最高,分别达2.41 U·mL−1和3.15 U·mL−1[129]。不同无机氮源对真菌和细菌植酸酶生产具有影响,相较于硝酸铵(NH4NO3)和其他天然氮源(酵母浸出物、蛋白胨、豆粉等),尿素(CH4N2O)和硫酸铵((NH4)2SO4)更有利于无花果曲霉(Aspergillus ficuum)生产植酸酶(20 IU·g−1 vs. 25 IU·g−1)[130]。微生物植酸酶的活性在很大程度上受土壤类型的影响,土壤中各成分对植酸酶活性的影响各不相同[131]。与砂土相比,粘土中微生物植酸酶活性显著降低35%[132]。Rao等[133]指出,黏土中Al3+氧化物可降低20%的微生物植酸酶活性。George等[129]发现,微生物植酸酶在砂土中吸附28 d后仍保持40%活性,而在粘土中活性仅为5%。

综上所述,微生物植酸酶活性的影响因素包括底物的种类和数量、反应体系的pH、温度以及土壤理化性质,这些因素影响微生物植酸酶生产速率、底物扩散速率与酶降解速率等,进而影响土壤植酸的矿化速率。

-

土壤中的有机磷由于生物可利用性较低,成为农作物的主要营养限制因子,合理开发利用土壤中的有机磷资源对可持续农业发展具有重要意义。植酸是土壤有机磷的主要成分,可在微生物植酸酶的矿化作用下水解为无机磷供植物吸收利用,微生物植酸酶可提高土壤植酸的生物利用率,降低磷肥的施加和投入,亦可减少土壤磷残留量,降低地表/地下水体的磷污染风险。

利用产植酸酶功能微生物进行对土壤植酸的降解,有耗能低、投资少、操作简单和二次污染小等优势。然而,现阶段对于充分发挥微生物植酸酶在土壤植酸水解中优势的实际应用仍显不足,鉴于此,今后可加强以下几方面的研究:(1)深入研究微生物植酸酶的空间结构,进一步阐明微生物植酸酶结构及其功能间的关系;(2)筛选酶活性高、热稳定性好的产植酸酶微生物,并采用基因重组技术生产微生物植酸酶;(3)研发经济、快速的微生物植酸酶分离提纯方法,提高纯化精度与速率,以提高微生物植酸酶产量;(4)使用固定化技术解决在微生物植酸酶生产、运输、使用及储存时保持其酶活性的问题;(5)通过蛋白质工程和基因工程改造微生物植酸酶基因,以降低生产成本、提高其产量。磷为不可再生资源,深入研究微生物植酸酶对土壤重要有机磷–植酸的矿化作用过程机制及矿化速率关键影响因素,对实现土壤有机磷的高效利用,降低外源磷肥施用及农业生产成本,且控制过量磷肥施用存在的潜在面源污染及水体富营养化风险具有重要的现实意义。

微生物植酸酶及其对土壤植酸的矿化作用综述

Microbial phytase and its role in phytate mineralization in soils: A review

-

摘要: 有机磷是土壤磷的主要存在形式,占比40%—90%,是作物磷营养的重要来源和储备库,亦是引起水体富营养化的潜在因子。磷作为植物生长发育的必需大量营养元素,通常以无机磷肥形式施用于土壤,易吸附于土壤表面或与钙、镁、铝、铁等金属阳离子形成难溶性络合物,导致其生物可利用性降低,其中20%—80%磷肥转化为有机磷,不易被植物吸收利用。矿化作用是在土壤微生物作用下,土壤中有机态化合物转化为无机态化合物的总称。土壤中有机磷主要以植酸及其盐类形式存在(占比50%—70%),植酸(盐)可被专一性酶(植酸酶)矿化水解为肌醇和磷酸(盐),并释放出无机磷,以供植物的根系直接吸收和利用。前期研究发现,缺磷胁迫下微生物可大量分泌植酸酶分解植酸,释放磷酸根,促使土壤有机磷水解矿化为无机磷,提高了土壤有机磷的生物可利用率。目前关于微生物植酸酶矿化植酸的研究多集中于谷类作物和动物营养,对土壤植酸矿化与土壤有机磷利用的综述性报道较少。因此,本文主要关注微生物植酸酶对土壤植酸的矿化作用与土壤有机磷利用,重点阐述其过程、机制和效率,包括微生物植酸酶的种类来源、酶学性质、作用机理和实际应用等方面的研究进展,可为提高土壤有机磷的生物利用效率、减少农业磷肥施用量、降低土壤磷流失及水体污染风险提供理论依据和技术支撑,为深入探究植酸酶功能并应用于农业生产实践及保障生态环境安全提供基础信息和参考。Abstract: Soil organic phosphorus (Po) is the predominant form of phosphorus (P) in soils which accounts for 40%—90% of soil total P (Pt). Therefore, it is an important P source for crop nutrition and also a potential factor for water eutrophication. Phosphorus is an essential element for plant growth, which is often applied to land as inorganic phosphate (Pi) fertilizers. Once into soils, P is readily sorbed on soils or bound with metal cations such as calcium, magnesium, aluminum, and iron, thereby being less bioaccessible. 20%—80% of P fertilizer can be transformed to Po, rendering it reluctant to be utilized by plants. Mineralization is the transformation of soil organic compounds into inorganic compounds with the help of microbes. Phytate is the predominant fraction of Po (50%—70%), which can be mineralized or hydrolyzed to inositol and P by the specific enzyme—phytase, releasing P for root uptake and plant growth. Microbes can secret phytase to hydrolyze phytate to release phosphate under P-deficiency stresses, thereby improves the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of soil phytate. At present, studies on microbial phytate mineralization by phytase mainly focus on cereal and poultry nutritional aspects, limited review papers on soil phytate mineralization and its P utilization by plants. Therefore, this paper reviews microbial phytase and its roles in soil phytate mineralization, with the emphasis on mineralization processes, mechanisms and efficiencies. These include the research progress on phytase’s species, sources, enzymatic properties, functional mechanisms, and its practical application efficiencies. The information provides theoretical foundation and technical support for improving soil Po utilization efficiency and reducing P fertilizer consumption and risk of P runoff and water eutrophication. In addition, this paper provides basic information and reference for further investigating microbial phytase to better its practical application in agricultural production and ecological environment safety protection.

-

Key words:

- phosphorus /

- microorganism /

- phytase /

- phytate /

- mineralization /

- agricultural production

-

磷作为植物生长及发育必需大量营养元素,通常以无机磷肥形式施用于土壤[1]。无机磷肥进入土壤后,极易被土壤固相吸附或与钙镁等金属阳离子形成难溶性络合物,导致其植物可利用性降低。此外,20%—80%磷肥转化为有机磷,占土壤全磷的40%—90%,仅约0.1%可被植物直接吸收利用[2]。因此,为保障农作物营养和产量,常施用过量磷肥,造成严重且广泛的环境污染问题[3]。磷肥的大量施用导致土壤酸化和植物营养失衡,且易在土壤中富集,造成土壤磷污染,并通过地表/地下水进入到水体中,引起水体的富营养化[4]。据此,提高土壤有机磷的植物利用率可优化农作物生产、降低磷肥施用量、降低磷流失及水体污染风险。

矿化作用是在土壤微生物作用下,土壤中有机态化合物转化为无机态化合物的总称。植酸(肌醇六磷酸)是土壤有机磷的主要存在形态(50%—70%)[5]。然而,植物根系难以直接吸收植酸,通常植酸需被专一性酶(植酸酶)水解生成植物能够吸收利用的正磷酸盐(磷酸氢根、磷酸二氢根)[6]。植酸酶(肌醇六磷酸水解酶)属于一类特殊的酸性磷酸单酯水解酶,能有效催化植酸及其盐类水解并产生肌醇衍生物和磷酸盐,可由土壤微生物分泌至植物根际环境中发挥作用[7]。植酸酶基因(phyA)由Richardson等[8]在黑曲霉(Aspergillus niger)中发现,并将其转入拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliaha),转基因拟南芥相较于野生型拟南芥的植酸酶活性由3.9—14.3 U·mg−1提高至224—14980 U·mg−1,其生长和磷营养得到显著改善,表明转基因植物可通过表达微生物植酸酶基因,高效分泌植酸酶进而有效利用植酸。Nelson等[9]首次证实饲料中的植酸可经过微生物植酸酶水解,释放出磷元素,极大推动微生物植酸酶的研究进展。随后一系列关于植酸酶提高植酸磷生物利用率的研究证实,微生物植酸酶基因可以显著促进植酸酶分泌,进而提高基质中植酸的分解效率,可为植物提供充足的磷营养[10]。因此,微生物是驱使土壤植酸矿化的关键因子,可高效分解难利用态有机磷,补偿植物根际有效/活性磷,是植物生长的重要磷源[11]。

近年来,伴随着对微生物植酸酶的研究逐步深入,关于其在农业领域的应用已引起广泛关注。目前,研究多集中于各类微生物植酸酶对谷类作物植酸矿化和在家禽动物营养中的作用,关于其对土壤植酸矿化与土壤有机磷利用的系统性综述报道较少。由此,本文主要关注微生物植酸酶对土壤植酸的矿化作用,重点阐述其过程、机制和效率,包括微生物植酸酶的种类来源、酶学性质、作用机理和实际应用等方面的研究进展。该综述可为提高土壤有机磷的生物利用率、减少农业磷肥施用、降低土壤磷流失及水体污染风险提供理论依据和技术支撑,为深入探究植酸酶功能并应用于农业生产实践及保障生态环境安全提供参考。

1. 植酸来源与应用(Origin and application of phytate)

植酸是一种有机磷化合物,属维生素B族的一类环己六醇磷酸酯,为饱和环状酸,易溶于水、甘油和丙二醇等,不溶于苯、氯仿和乙烷等。植酸的分子式是C6H18O24P6,分子量660,化学名称为环已六醇–1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6–六磷酸二氢酯,其化学构造由1分子肌醇和6分子磷酸结合而形成,即肌醇的6个碳原子上羟基均被磷酸酯化生成的肌醇衍生物(图1A)[12]。在植物中植酸主要存在于种子里,其中以豆科、谷物、油籽和坚果作物种子的含量最丰富,其含量达1%—3%,占植物体内总磷含量的40%—90%,是植物种子/谷类作物中肌醇和磷酸的重要储备库[13]。

植酸的结构稳定,高温(>120 ℃)可分解,其中6个磷酸基团拥有比较强的螯合能力,可与金属阳离子(如Ca2+、Mg2+、Cu2+、Zn2+、Fe3+等)形成极稳定的螯合物,降低营养元素的生物有效性,降低植物和家禽等动物对矿质元素的吸收,因而被称为抗营养因子[14]。此外,植酸可与蛋白质进行络合反应,其作用形式与蛋白质的等电点有关,比蛋白质等电点低时,植酸和蛋白质分子上的碱性基团发生反应,形成很稳定的蛋白质络合物,影响动物体内的蛋白酶活性(如胃蛋白酶、胰蛋白酶和淀粉蛋白酶等);较蛋白质等电点高时,植酸通过Ca2+、Mg2+等金属阳离子连接形成“植酸–金属离子–蛋白质”复合物,同样可以降低蛋白酶活性[15]。植酸的络合能力与乙二胺四乙酸(EDTA)相似,但因其独特性质(稳定护色、抗氧化性、耐腐蚀性等),相较于EDTA应用更为广泛,主要应用于食品工业中作为果蔬及水产的护色剂和保鲜剂、医药领域中作为止渴剂、生物学领域中作为发酵促进剂促进微生物代谢、金属加工领域中作为防锈剂和防蚀剂等[16]。

2. 微生物植酸酶(Microbial phytase)

植酸酶,属磷酸单酯水解酶,能催化植酸及其盐类水解为肌醇和磷酸盐,具有特殊空间结构(图1A),可使植酸脱磷酸化,并释放无机磷酸盐[17]。植酸酶主要存在于微生物以及动植物中,由于微生物分布的广泛性及其植酸酶具有易分离提纯、稳定性强、活性高等动植物植酸酶不具备的特点,目前对微生物(细菌、真菌、酵母菌等)植酸酶的研究最为广泛[18]。

2.1 种类与来源

美国国立生物技术信息中心(national center for biotechnology information, NCBI)的蛋白质数据库里细菌植酸酶数量远多于真菌植酸酶。目前已报道的产植酸酶细菌主要包括淀粉乳杆菌(Lactobacillus amylovorus)、大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)、肠杆菌(Enterobacter sp.)、枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis)、地衣芽孢杆菌(Bacillus licheniformis)、解淀粉芽孢杆菌(Bacillus amyloliquefaciens)、克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella sp.)、假单胞菌(Pseudomonas sp.)、反刍月形单胞菌(Selenomonas ruminantium)、链球菌(Streptococcus sp.)、嗜酸乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus acidophilus)和干酪乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus casei)等。细菌植酸酶具有较高的热稳定性(如芽孢杆菌(Bacillus sp.)植酸酶)—70 ℃温浴10 min后仍具有100%的酶活性,以及高蛋白水解稳定性(如大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)植酸酶)—植酸酶蛋白质浓度可达菌体总蛋白的47%,在植酸水解和有机磷利用等方面有着良好应用前景[19]。例如,表达植酸酶基因的大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)具有繁殖快、表达量高、成本低的特点[20]。但糖基化是细菌表达载体生产植酸酶的主要问题,由于蛋白质产物在大量表达时极易产生错误的折叠致使酶活性丧失,因此糖基化的不同程度对于细菌植酸酶的热稳定性有着重要影响[13]。

在微生物中,真菌植酸酶的活性最强,而且真菌植酸酶通常为便于分离纯化的胞外酶,所以真菌多用于工业化生产植酸酶[21]。产植酸酶真菌主要包括无花果曲霉(Aspergillus ficuum)、土曲霉(Aspergillus terreus)、米曲霉(Aspergillus oryzae)、烟曲霉(Aspergillus fumigatus)、黑曲霉(Aspergillus niger)、青霉菌(Penicillium)等[22]。研究已证明黑曲霉(Aspergillus niger)植酸酶活性较高,其植酸酶基因phyA已在多种真菌中成功表达,而其他真菌植酸酶活性较低,且曲霉(Aspergillus sp.)植酸酶生产安全性较好,因此是目前工业化生产应用较多的真菌[23]。

酵母菌的致病性比较低,是植酸酶产生菌理想的研究对象,但当前对酵母菌植酸酶的研究较少,尚缺少工业化生产。已知主要的产植酸酶酵母菌分别有热带假丝酵母(Candida tropicalis)、毕赤酵母(Pichia pastoris)、酿酒酵母(Saccharomyces cerevisiae)等[24]。在众多产植酸酶的酵母菌中,斯巴达克毕赤酵母(Pichia spartinae)植酸酶的活性最高[25]。酵母菌的遗传信息较为全面,而且便于操作,来自细菌和真菌的异源植酸酶基因已在酵母菌中成功表达,由于外源蛋白表达时容易出现过度糖基化,阻碍合成蛋白的分泌和运输,故目前可作为表达载体的酵母菌种类较少,主要为毕赤酵母(Pichia pastoris)[26]。

2.2 产植酸酶微生物的分离与鉴定

为分离具有胞外植酸酶活性的细菌、真菌和酵母菌,已开展较多关于产植酸酶微生物筛选的研究。Richardson和Hadobas[27]使用含植酸钠的筛选培养基,从土壤中分离出238种产植酸酶细菌,其中,4株假单胞菌(Pseudomonas spp.)植酸酶活性较高,分别是荧光假单胞菌(fluorescent Pseudomonas)—恶臭假单胞菌(Pseudomonas putida)CCAR53和CCAR59、非荧光假单胞菌(nonfluorescent Pseudomonas)—门多萨假单胞菌(Pseudomonas mendocina)CCAR31和CCAR60,其植酸酶活性分别是13.4×10−3、13.3×10−3、7.3×10−3、6.9×10−3 U·mg−1,分别从植酸钠释放出57%和54%无机磷。1994年,Volfová等[28]筛选得到132种产植酸酶微生物,其中胞外活性植酸酶主要来自真菌。随后,Gargova等[29]通过两步筛选(合成植酸酶琼脂培养基初步筛选和玉米淀粉液体培养基二次筛选)得到203种产植酸酶真菌。Lambrechts等[30]首次发现酵母菌Schwanniomyces castellii分泌物具有极高的植酸酶活性(237 U·mg−1),是其他菌株植酸酶活性的2.8倍。Sano等[31]筛选得到约1200株酵母菌株,以植酸作为唯一磷源进行培养,发现除酵母白囊杆菌(Arxula adeninivorans)外,大多数微生物无法生长,表明该微生物具有分泌植酸酶和降解植酸的能力。

Bae等[32]建立了一种定性分析微生物植酸酶活性的方法,即用特异性琼脂培养基中沉淀态植酸钙/植酸钠的减少作为具有酶活指示。Engelen等[33]建立了简便快捷的定量分析微生物植酸酶活性的方法,即测定pH 5.5时,植酸钠分解释放无机磷含量。然而,仍有大量的产植酸酶微生物有待鉴定。目前,通过NCBI的蛋白质数据库和基因组数据库中同源序列鉴定,发现许多可以在自然环境下分泌胞外植酸酶的微生物。

分离筛选的微生物可用液态深层发酵技术(submerged fermentation,SmF)及固态发酵技术(solid state fermentation,SSF)生产植酸酶[34]。其中,SmF作为主要的生产技术已被广泛使用,其特点是发酵的周期短、劳动的强度低与生产率高等,特别适用于细菌和酵母菌的植酸酶生产[35]。SSF是微生物在没有或基本没有游离水的固态基质上的发酵方法,近年来,作为“高产量低成本”的生产技术,SSF在微生物植酸酶生产方面表现出极大优势,如微生物易生长、酶活性高、酶系丰富,发酵过程中无需严格的无菌条件,设备构造及后续处理简单、且易操作、能耗低、投资少、污染小等[36]。真菌植酸酶生产可通过SmF或SSF[37]。培养条件、菌种类型、底物性质和养分有效性是影响微生物植酸酶产量的关键因素。Han等[38]采用半固体底物发酵的方式生产植酸酶,发现固态发酵产生植酸酶含量比液态发酵高2—20倍。Papagianni等[39]研究SmF和SSF中培养基组成、黑曲霉形态和植酸酶产量之间的相关性关系,发现培养基组成和真菌形态对SmF生产方式中植酸酶的产生影响较大,随后添加有机磷酸盐,均可促进SmF及SSF中黑曲霉生长与植酸酶产生,其植酸酶活性分别由6770 U·mg−1和162 U·mg−1提高至8090 U·mg−1和1800 U·mg−1。这些研究表明在选择特定生产技术时,应当考虑培养的条件、菌种的类型、底物的性质和养分有效性等重要因素的影响。

2.3 微生物植酸酶分类与酶学性质

微生物植酸酶的种类繁多,其结构各不相同,催化机制也各有不同,目前各种微生物的植酸酶种类与酶学性质(最适温度/pH、分子量、米氏常数Km值、特异性酶活性)分别见表1、2。

表 1 微生物植酸酶种类及其植酸矿化机制Table 1. Microbial phytase species and phytate mineralization mechanisms分类方式Classification methods 植酸酶种类Phytase species 结构特征Structural properties 植酸矿化机制Phytate mineralization mechanisms 微生物Microbes 参考文献References 植酸发生水解脱磷酸化的位置 3–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.8) 存在1个开放阅读框(ORF);2个外显子被1个真菌内含子隔开;内含子均有相同特征保守序列:供体序列GTRNGC;索套序列RCTRAC;受体序列YAG 从肌醇3-C位催化水解酯键,依次释放其他碳位的磷 克雷伯氏菌属(Klebsiella sp.) [40] 淀粉乳杆菌(Lactobacillus amylovorus) [41] 植酸发生水解脱磷酸化的位置 3–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.8) 存在1个开放阅读框(ORF);2个外显子被1个真菌内含子隔开;内含子均有相同特征保守序列:供体序列GTRNGC;索套序列RCTRAC;受体序列YAG 从肌醇3-C位催化水解酯键,依次释放其他碳位的磷 埃氏巨型球菌(Megasphaera elsdenii) [42] 光岗菌(Mitsuokella multiacidus、Mitsuokella jalaludinii) [42-43] 6–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.26) 含有共同的活性位点保守序列RHGXRXP 从肌醇6-C位启动脱磷酸化 大肠杆菌(Escherichia coil) [19] 催化机制 组氨酸酸性磷酸酶(HAP) N-末端基元:RHGXRXPC-末端基元:HD N-末端基元RHGXRXP中组氨酸(H)残基亲核攻击磷酸基团形成一个共价磷酸-组氨酸中间体,然后C-末端基元HD中天冬氨酸(D)残基向即将断裂的磷酸单酯键的氧原子提供质子,磷酸-组氨酸中间体水解消耗一分子水游离出磷酸基团,反应过程无需金属离子参与 阴沟肠杆菌(Enterobacter cloacae) [44] 肠杆菌属(Enterobacter sp.) [45] 产气克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella aerogenes) [46] 肺炎克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella pneumoniae) [47] 土生克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella terrigena) [48] 产酸克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella oxytoca) [49] 变形肥杆菌(Obesumbacterium proteus) [50] 成团泛生菌(Pantoea agglomerans) [51] 普氏菌属(Prevotella sp.) [52] 丁香假单胞菌(Pseudomonas syringae) [53] 草莓假单胞菌(Pseudomonas fragi) [54] 密螺旋菌体属(Treponema sp.) [52] 中间耶尔森菌(Yersinia intermedia) [55] 隔孢伏革菌(Peniophora lycii) [56] 无花果曲霉菌(Aspergillus ficuum) [57] 黑曲霉菌(Aspergillus niger) [58] β螺旋植酸酶(BPP) 主要由β-折叠片组成,形状类似6叶β螺旋桨 BPP具有2个不对称磷酸基团结合部位,“切割部位”(Cleavage site,CS)和“亲和部位”(Affinity site,AS),AS促进植酸分子结合,而CS负责水解磷酸基团 解淀粉芽孢杆菌(Bacillus amyloquefaciens) [59] 地衣芽孢杆菌(Bacillus licheniformis) [60] 枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis) [61] 芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus sp.) [62] 布氏柠檬酸杆菌(Citrobacter braakii) [63] 半胱氨酸植酸酶(CP) 包含活性部位基元HCXXGXXR(T/S) 活性部位形成一个含保守半胱氨基酸(C241)的磷酸基团结合环(Phosphate-binding loop,P-loop),其中C241的不可逆氧化使P-loop由非活性的开放构象转变为活性的闭合构象,P-loop充当特异底物的结合环,其深度决定底物的特异性。CP有一个较深的P-loop,能适应植酸分子充分磷酸化而呈负电性的肌醇环,有利的静电环境促进底物植酸分子分解 反刍月形单胞菌(Selenomonas ruminantium) [64] 假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas sp.) [65] 催化机制 紫色酸性磷酸酶(PAP) 包含特有的7个金属配合氨基酸残基,7个残基(D、D、Y、N、H、H、H)包含在5个保守基元中(DXG/GDXXY/GNH(ED)/VXXH/GHXH) PAP包括具有植酸酶活性的蛋白AtPAP15能够降低植酸含量 伯克霍尔德菌属(Burkholderia sp.) [66] 表 2 微生物植酸酶的酶学性质Table 2. The enzymatic properties of microbial phytase微生物Microbes 最适温度/℃Temperature optimum 最适pHpH optimum 分子量/(KDa)Molecular weight Km/(μmol) 特异性酶活性/(U·mg−1)Specific activity 参考文献References 细菌 解淀粉芽孢杆菌(Bacillus amyloliquefaciens) 70 — 42 — — [67] 枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis) 60 6—6.5 36—38 500 8.7 [68] 地衣芽孢杆菌(Bacillus licheniformis) 55, 65 4.5—6 44, 47 — — [69] 芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus sp.) 70 7 44 550 20 [70] 布氏柠檬酸杆菌(Citrobacter braakii) 50 4 47 460 1122 [63] 大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli) 60 4.5 42 130 811 [71] 肠杆菌属(Enterobacter sp.) 50 7—7.5 — 700 — [45] 产气克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella aerogenes) — — 10—13 — — [46] 肺炎克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella pneumoniae) 50 4 — — — [47] 土生克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella terrigena) 58 5 40 300 205 [72] 产酸克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella oxytoca) 55 5–6 — — — [49] 变形肥杆菌(Obesumbacterium proteus) 40–45 4.9 45 340 310 [56] 成团泛生菌(Pantoea agglomerans) 60 4.5 42 340 140 [73] 构巢裸壳孢菌(Emericella nidulans) — 6.5 66 — 29–33 [62] 丁香假单胞菌(Pseudomonas syringae) 40 5.5 45 380 2.514 [53] 左旋乳酸芽孢杆菌(Bacillus laevolacticus) 70 7–8 41–46 — 12.69 [74] 戊糖乳杆菌(Lactobacillus pentosus) 50 5 69 — — [75] 植物乳杆菌(Lactobacillus plantarum) 65 5.5 52 — 0.463 [76] 假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas sp.) — 5, 7 — — — [27] 绿脓假单胞菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa) 50 5–8 — — — [27] 反刍月形单胞菌(Selenomonas ruminantium) 50–55 4–5.5 46 — 0.6 [77] 克雷伯菌属(Klebsiella sp.) 37 6 10–13 2000 62.5 [78] 蜡孔菌属(Ceriporia sp.) 40–60 5–6 59 — 700 ± 80 [79] 绒毛拴菌(Trametes pubescens) 40–60 5–6 62 — 1210 ± 30 [79] 弗氏柠檬酸杆菌(Citrobacter freundii) 52 2.7, 5 — — — [80] 无丙二酸柠檬酸杆菌(Citrobacter amalonaticus) — — — — 6413 [81] 细菌 疏棉状嗜热丝孢菌(Thermomyces lanuginosus) 75 6 52 — 110 [82] 嗜热毁丝菌(Myceliophthora thermophila) 62 5.5 — — — [83] 嗜热篮状菌(Talaromyces thermophilus) — — 128 — — [83] 中间耶尔森菌(Yersinia intermedia) 55 4.5 45 — 3960 [55] 克氏耶尔森氏菌(Yersinia kristeensenii) 55 4.5 — — — [84] 香蕉狄克氏菌(Dickeya paradisiaca) 55 4.5, 5.5 — — — [85] 旧金山乳杆菌(Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis) 45 4 — — — [86] 真菌 曲霉菌属(Aspergillus sp.) — — 70 — — [8] 无花果曲霉菌(Aspergillus ficuum) 63 2.5 68 27 1.1 [57] 黑曲霉菌(Aspergillus niger) 65 5 84 100 103 [58] 炭黑曲霉菌(Aspergillus carbonarius) 53 4.7 — — — [87] 土曲霉菌(Aspergillus terrus) 70 4.5 60 11 142 [62] 烟曲霉菌(Aspergillus fumigatus) 60 6 — — 43 [88] 产黄青霉菌(Penicillium chrysogenum) — — — — 2.86 [89] 简青霉菌(Penicillium simplicissimum) 60 3.5–5.3 65 — 3.8 [90] 草酸青霉菌(Penicillium oxalicum) 55 4.5 62.5 370 307 [91] 枝孢霉菌属(Cladosporium sp.) 40 3.5 32.6 15.2 910 [92] 米根霉菌(Rhizopus oryzae) 55 4.5 — — — [93] 少孢根霉菌(Rhizopus oligosporus) 55 4.5 — 150 9.47 [94] 微小根毛霉菌(Rhizomucor pusillus) 70 5.4 — — — [95] 嗜热侧孢霉菌(Sporotrichum thermophile) 58 5 — — — [96] 隔孢伏革菌(Peniophora lycii) 50–55 4–4.5 72 100 1080 ± 110 [56] 米曲霉菌(Aspergillus oryzae) 50 5.5 120 330 0.35 [97] 酵母菌 克鲁斯假丝酵母(Candida krusei) 40 2.5, 5.5 330 30 1210 [98] 毕赤酵母菌(Pichia pastoris) 60 2.5, 5.5 95 — 25–65 [99] 异常毕赤酵母菌(Pichia anomala) 60 4 64 200 — [100] 斯巴达克毕赤酵母(Pichia spartinae) 60 2.5 95 — — [25] 西方许旺酵母(Schwanniomyces occidentalis) 70 4.5 70 380 — [25] 酿酒酵母菌(Saccharomyces cerevisiae) 55–60 2–2.5, 5–5.5 120 — 4 [101] 芽殖酵母菌(Saccharomyces castellii) 77 4.4 490 — 0.3–8 [102] 酵母白囊杆菌(Arxula adeninivorans) 75 4.5 — 230 — [31] 依据植酸发生水解脱磷酸化的位置,微生物植酸酶可以分成3类:3–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.8)、6–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.26)及5–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.72),分别是在植酸的第3位、6位及2位碳原子上水解释放磷酸基因[27]。根据其来源,可分为3类:细菌植酸酶、真菌植酸酶、酵母菌植酸酶[103]。根据酶活最适pH,可分成酸性植酸酶(最适pH=5—6)和碱性植酸酶(最适pH=8—10),真菌及多数细菌分泌酸性植酸酶,少数细菌分泌中性(最适pH=7—7.5)或碱性植酸酶[104]。根据催化机制,可分为4类:组氨酸酸性磷酸酶(histidine acid phosphate,HAP),大多来源于肠杆菌(Enterobacter sp.)及真菌,当前应用较为普遍;β螺旋植酸酶(β–propeller phytase,BPP),多数来源于芽孢杆菌(Bacillus sp.),具有较强的稳定性;然而半胱氨酸植酸酶(cysteine phytase,CP),只发现存在于瘤胃微生物(rumen microbiome);紫色酸性磷酸酶(purple acid phosphate,PAP),在真菌以及细菌中分布广泛[52]。

植酸酶来源不相同,其最适pH差异亦较大[105]。细菌、真菌、酵母菌植酸酶最适pH分别为2.7—8.0、2.5—6.0、2.5—5.5,通常微生物植酸酶活性pH值是4.0–7.5,在当pH<3.0或>7.5时,其酶活性急剧下降至失活[106]。微生物植酸酶活性温度为50—70 ℃,细菌、真菌、酵母菌植酸酶最适温度为分别为37—75 ℃、40—70 ℃、40—77 ℃,45—60 ℃活性较为稳定,更高温度(>80 ℃)易失活[107]。

3. 微生物植酸酶对土壤植酸的矿化作用(Phytate mineralization by microbial phytase)

3.1 矿化过程

谷物饲料中含有大量植酸(盐),家畜难以直接消化利用,故植酸(盐)以未分解形式通过家畜排泄物进入土壤,此外,农业生产过程施用的大量无机磷肥可转化为植酸有机磷,造成土壤植酸积累[103]。微生物通过分泌植酸酶水解土壤植酸,释放无机磷供植物直接吸收(图1B)。Chen等[108]指出,土壤植酸矿化分解与植酸酶数量和活性具有显著相关性。Bünemann[109]指出,>60%土壤有机磷可被磷酸酶水解,其中植酸酶释放的磷高达80%。Tarafdar等[110]发现,微生物植酸酶能有效水解土壤植酸从而释放无机磷酸盐,比动植物植酸酶效率高约50%。以上研究表明,微生物是驱动土壤植酸矿化的关键因子,对提高土壤有机磷的利用率具有重要作用。

植酸的矿化机制虽在上世纪60年代已被研究,但当前植酸的代谢途径和形成产物仍然是植酸酶研究的重点。随着分离方法的发展,尤其是色谱技术在矿化产物分析中的广泛应用,发现不同来源植酸酶的作用机理存在差别[111],其中,微生物植酸酶矿化植酸的途径为:植酸→DL-1,2,4,5,6–五磷酸肌醇→DL-1,2,5,6-四磷酸肌醇→DL-1,2,5-三磷酸肌醇/DL-1,2,6-三磷酸肌醇/DL-2,5,6-三磷酸肌醇→DL-1,2-二磷酸肌醇/2,5-二磷酸肌醇/DL-2,6-二磷酸肌醇→2-磷酸肌醇(图2)[112]。

3.2 矿化效率影响因素

微生物植酸酶活性是植酸矿化效率的主要影响因子(表2),而微生物植酸酶活性受生物和物理化学过程的影响[113],前者引起酶生产速率、同工酶(催化相同反应而分子结构不同的酶)生产和微生物群落组成的变化,后者引起吸附解吸反应、底物扩散速率和酶降解速率的变化[114]。影响酶活性的关键因素包括:

(1)微生物植酸酶活性由底物种类和数量等几个相互关联的因素共同决定[115]。通常使用添加不同底物的方法来测定微生物的植酸酶活性,包括萘磷酸、6–磷酸葡萄糖、2–甘油磷酸、植酸钠、植酸钙、β–甘油磷酸盐、对硝基苯酚磷酸盐、6–磷酸果糖、一磷酸腺苷(adenosine–5’–monophosphate,AMP)、二磷酸腺苷(adenosine–5’–diphosphate,ADP)、三磷酸腺苷(adenosine–5’–triphosphate,ATP)、三磷酸鸟苷(guanosine–5’–triphosphate,GTP)和烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸(nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate,NADP)等[116]。根据底物的差异,将其分成特异性及非特异性酸性磷酸酶[117]。研究发现,一些微生物植酸酶对植酸具高特异性,如芽孢杆菌(Bacillus sp.)、曲霉菌(Aspergillus sp.)和大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)[118],其中枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis)植酸酶活性随植酸浓度增加而增加,最高活性可达10 mmol[119]。

(2)反应体系的pH对微生物植酸酶活性具有一定影响。微生物植酸酶比植物植酸酶具有更宽泛的pH适宜范围,但其最适pH因微生物种类而存在差异[30]。植酸酶主要分成碱性植酸酶以及酸性植酸酶,其最适pH值范围是5.0–8.0[59]。真菌植酸酶的最适pH值为4.5–6.5,如烟曲霉(Aspergillus fumigatus)[120]。丝核菌(Rhizoctonia sp.)和镰刀菌(Fusarium verticillioides)在pH分别为4.0和5.0时分泌植酸酶[121]。而细菌植酸酶在pH值分别为6.0和8.0时活性最强,如芽孢杆菌(Bacillus sp.)[62]。因此,控制适宜反应体系的pH值对保障微生物植酸酶的产量及其活性有利。

(3)温度是微生物植酸酶活性的重要影响因素,既影响微生物活性(即植酸酶的生成与产量),亦影响酶的活性(即植酸矿化速率)[122]。一般通过计算活化能(Ea)来确定酶对温度的响应,两个过程(生产和降解)的速率本应随着温度的升高而增加,但由于Ea的差异,它们表现出不同的温度敏感性[123]。研究表明,微生物植酸酶的温度敏感性随季节变化,并且在单一环境中存在差异[124]。与温暖气候相比,微生物在寒冷气候中分泌植酸酶的最适温度较低、结构灵活性和改变结构的能力较差[125]。微生物植酸酶的最适温度范围为35—77 ℃,镰刀菌(Fusarium verticillioides)植酸酶最适温度为50 ℃,其稳定性可保持至60 ℃,而克雷伯菌属(Klebsiella sp.)植酸酶在较低温度37 ℃保持最大活性[126]。Johnson等[127]研究指出,产植酸酶微生物的代谢速率随温度升高而加快,平均Ea为0.62 eV。因此,与酶动力学本身相比,温度对微生物植酸酶的代谢速率起着更为重要的作用。

(4)土壤理化性质的影响,包括全氮含量和土壤质地类型[128]。氮是微生物植酸酶生产中不可缺少的元素,对不同氮源影响微生物植酸酶产量的研究发现,在麦麸培养基和桔皮粉培养基中添加0.1%磷酸二氢铵(NH4H2PO4)时微生物植酸酶产量最高,分别达2.41 U·mL−1和3.15 U·mL−1[129]。不同无机氮源对真菌和细菌植酸酶生产具有影响,相较于硝酸铵(NH4NO3)和其他天然氮源(酵母浸出物、蛋白胨、豆粉等),尿素(CH4N2O)和硫酸铵((NH4)2SO4)更有利于无花果曲霉(Aspergillus ficuum)生产植酸酶(20 IU·g−1 vs. 25 IU·g−1)[130]。微生物植酸酶的活性在很大程度上受土壤类型的影响,土壤中各成分对植酸酶活性的影响各不相同[131]。与砂土相比,粘土中微生物植酸酶活性显著降低35%[132]。Rao等[133]指出,黏土中Al3+氧化物可降低20%的微生物植酸酶活性。George等[129]发现,微生物植酸酶在砂土中吸附28 d后仍保持40%活性,而在粘土中活性仅为5%。

综上所述,微生物植酸酶活性的影响因素包括底物的种类和数量、反应体系的pH、温度以及土壤理化性质,这些因素影响微生物植酸酶生产速率、底物扩散速率与酶降解速率等,进而影响土壤植酸的矿化速率。

4. 结论与展望(Conclusions and prospects)

土壤中的有机磷由于生物可利用性较低,成为农作物的主要营养限制因子,合理开发利用土壤中的有机磷资源对可持续农业发展具有重要意义。植酸是土壤有机磷的主要成分,可在微生物植酸酶的矿化作用下水解为无机磷供植物吸收利用,微生物植酸酶可提高土壤植酸的生物利用率,降低磷肥的施加和投入,亦可减少土壤磷残留量,降低地表/地下水体的磷污染风险。

利用产植酸酶功能微生物进行对土壤植酸的降解,有耗能低、投资少、操作简单和二次污染小等优势。然而,现阶段对于充分发挥微生物植酸酶在土壤植酸水解中优势的实际应用仍显不足,鉴于此,今后可加强以下几方面的研究:(1)深入研究微生物植酸酶的空间结构,进一步阐明微生物植酸酶结构及其功能间的关系;(2)筛选酶活性高、热稳定性好的产植酸酶微生物,并采用基因重组技术生产微生物植酸酶;(3)研发经济、快速的微生物植酸酶分离提纯方法,提高纯化精度与速率,以提高微生物植酸酶产量;(4)使用固定化技术解决在微生物植酸酶生产、运输、使用及储存时保持其酶活性的问题;(5)通过蛋白质工程和基因工程改造微生物植酸酶基因,以降低生产成本、提高其产量。磷为不可再生资源,深入研究微生物植酸酶对土壤重要有机磷–植酸的矿化作用过程机制及矿化速率关键影响因素,对实现土壤有机磷的高效利用,降低外源磷肥施用及农业生产成本,且控制过量磷肥施用存在的潜在面源污染及水体富营养化风险具有重要的现实意义。

-

表 1 微生物植酸酶种类及其植酸矿化机制

Table 1. Microbial phytase species and phytate mineralization mechanisms

分类方式Classification methods 植酸酶种类Phytase species 结构特征Structural properties 植酸矿化机制Phytate mineralization mechanisms 微生物Microbes 参考文献References 植酸发生水解脱磷酸化的位置 3–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.8) 存在1个开放阅读框(ORF);2个外显子被1个真菌内含子隔开;内含子均有相同特征保守序列:供体序列GTRNGC;索套序列RCTRAC;受体序列YAG 从肌醇3-C位催化水解酯键,依次释放其他碳位的磷 克雷伯氏菌属(Klebsiella sp.) [40] 淀粉乳杆菌(Lactobacillus amylovorus) [41] 植酸发生水解脱磷酸化的位置 3–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.8) 存在1个开放阅读框(ORF);2个外显子被1个真菌内含子隔开;内含子均有相同特征保守序列:供体序列GTRNGC;索套序列RCTRAC;受体序列YAG 从肌醇3-C位催化水解酯键,依次释放其他碳位的磷 埃氏巨型球菌(Megasphaera elsdenii) [42] 光岗菌(Mitsuokella multiacidus、Mitsuokella jalaludinii) [42-43] 6–植酸酶(EC 3.1.3.26) 含有共同的活性位点保守序列RHGXRXP 从肌醇6-C位启动脱磷酸化 大肠杆菌(Escherichia coil) [19] 催化机制 组氨酸酸性磷酸酶(HAP) N-末端基元:RHGXRXPC-末端基元:HD N-末端基元RHGXRXP中组氨酸(H)残基亲核攻击磷酸基团形成一个共价磷酸-组氨酸中间体,然后C-末端基元HD中天冬氨酸(D)残基向即将断裂的磷酸单酯键的氧原子提供质子,磷酸-组氨酸中间体水解消耗一分子水游离出磷酸基团,反应过程无需金属离子参与 阴沟肠杆菌(Enterobacter cloacae) [44] 肠杆菌属(Enterobacter sp.) [45] 产气克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella aerogenes) [46] 肺炎克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella pneumoniae) [47] 土生克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella terrigena) [48] 产酸克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella oxytoca) [49] 变形肥杆菌(Obesumbacterium proteus) [50] 成团泛生菌(Pantoea agglomerans) [51] 普氏菌属(Prevotella sp.) [52] 丁香假单胞菌(Pseudomonas syringae) [53] 草莓假单胞菌(Pseudomonas fragi) [54] 密螺旋菌体属(Treponema sp.) [52] 中间耶尔森菌(Yersinia intermedia) [55] 隔孢伏革菌(Peniophora lycii) [56] 无花果曲霉菌(Aspergillus ficuum) [57] 黑曲霉菌(Aspergillus niger) [58] β螺旋植酸酶(BPP) 主要由β-折叠片组成,形状类似6叶β螺旋桨 BPP具有2个不对称磷酸基团结合部位,“切割部位”(Cleavage site,CS)和“亲和部位”(Affinity site,AS),AS促进植酸分子结合,而CS负责水解磷酸基团 解淀粉芽孢杆菌(Bacillus amyloquefaciens) [59] 地衣芽孢杆菌(Bacillus licheniformis) [60] 枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis) [61] 芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus sp.) [62] 布氏柠檬酸杆菌(Citrobacter braakii) [63] 半胱氨酸植酸酶(CP) 包含活性部位基元HCXXGXXR(T/S) 活性部位形成一个含保守半胱氨基酸(C241)的磷酸基团结合环(Phosphate-binding loop,P-loop),其中C241的不可逆氧化使P-loop由非活性的开放构象转变为活性的闭合构象,P-loop充当特异底物的结合环,其深度决定底物的特异性。CP有一个较深的P-loop,能适应植酸分子充分磷酸化而呈负电性的肌醇环,有利的静电环境促进底物植酸分子分解 反刍月形单胞菌(Selenomonas ruminantium) [64] 假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas sp.) [65] 催化机制 紫色酸性磷酸酶(PAP) 包含特有的7个金属配合氨基酸残基,7个残基(D、D、Y、N、H、H、H)包含在5个保守基元中(DXG/GDXXY/GNH(ED)/VXXH/GHXH) PAP包括具有植酸酶活性的蛋白AtPAP15能够降低植酸含量 伯克霍尔德菌属(Burkholderia sp.) [66] 表 2 微生物植酸酶的酶学性质

Table 2. The enzymatic properties of microbial phytase

微生物Microbes 最适温度/℃Temperature optimum 最适pHpH optimum 分子量/(KDa)Molecular weight Km/(μmol) 特异性酶活性/(U·mg−1)Specific activity 参考文献References 细菌 解淀粉芽孢杆菌(Bacillus amyloliquefaciens) 70 — 42 — — [67] 枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis) 60 6—6.5 36—38 500 8.7 [68] 地衣芽孢杆菌(Bacillus licheniformis) 55, 65 4.5—6 44, 47 — — [69] 芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus sp.) 70 7 44 550 20 [70] 布氏柠檬酸杆菌(Citrobacter braakii) 50 4 47 460 1122 [63] 大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli) 60 4.5 42 130 811 [71] 肠杆菌属(Enterobacter sp.) 50 7—7.5 — 700 — [45] 产气克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella aerogenes) — — 10—13 — — [46] 肺炎克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella pneumoniae) 50 4 — — — [47] 土生克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella terrigena) 58 5 40 300 205 [72] 产酸克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella oxytoca) 55 5–6 — — — [49] 变形肥杆菌(Obesumbacterium proteus) 40–45 4.9 45 340 310 [56] 成团泛生菌(Pantoea agglomerans) 60 4.5 42 340 140 [73] 构巢裸壳孢菌(Emericella nidulans) — 6.5 66 — 29–33 [62] 丁香假单胞菌(Pseudomonas syringae) 40 5.5 45 380 2.514 [53] 左旋乳酸芽孢杆菌(Bacillus laevolacticus) 70 7–8 41–46 — 12.69 [74] 戊糖乳杆菌(Lactobacillus pentosus) 50 5 69 — — [75] 植物乳杆菌(Lactobacillus plantarum) 65 5.5 52 — 0.463 [76] 假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas sp.) — 5, 7 — — — [27] 绿脓假单胞菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa) 50 5–8 — — — [27] 反刍月形单胞菌(Selenomonas ruminantium) 50–55 4–5.5 46 — 0.6 [77] 克雷伯菌属(Klebsiella sp.) 37 6 10–13 2000 62.5 [78] 蜡孔菌属(Ceriporia sp.) 40–60 5–6 59 — 700 ± 80 [79] 绒毛拴菌(Trametes pubescens) 40–60 5–6 62 — 1210 ± 30 [79] 弗氏柠檬酸杆菌(Citrobacter freundii) 52 2.7, 5 — — — [80] 无丙二酸柠檬酸杆菌(Citrobacter amalonaticus) — — — — 6413 [81] 细菌 疏棉状嗜热丝孢菌(Thermomyces lanuginosus) 75 6 52 — 110 [82] 嗜热毁丝菌(Myceliophthora thermophila) 62 5.5 — — — [83] 嗜热篮状菌(Talaromyces thermophilus) — — 128 — — [83] 中间耶尔森菌(Yersinia intermedia) 55 4.5 45 — 3960 [55] 克氏耶尔森氏菌(Yersinia kristeensenii) 55 4.5 — — — [84] 香蕉狄克氏菌(Dickeya paradisiaca) 55 4.5, 5.5 — — — [85] 旧金山乳杆菌(Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis) 45 4 — — — [86] 真菌 曲霉菌属(Aspergillus sp.) — — 70 — — [8] 无花果曲霉菌(Aspergillus ficuum) 63 2.5 68 27 1.1 [57] 黑曲霉菌(Aspergillus niger) 65 5 84 100 103 [58] 炭黑曲霉菌(Aspergillus carbonarius) 53 4.7 — — — [87] 土曲霉菌(Aspergillus terrus) 70 4.5 60 11 142 [62] 烟曲霉菌(Aspergillus fumigatus) 60 6 — — 43 [88] 产黄青霉菌(Penicillium chrysogenum) — — — — 2.86 [89] 简青霉菌(Penicillium simplicissimum) 60 3.5–5.3 65 — 3.8 [90] 草酸青霉菌(Penicillium oxalicum) 55 4.5 62.5 370 307 [91] 枝孢霉菌属(Cladosporium sp.) 40 3.5 32.6 15.2 910 [92] 米根霉菌(Rhizopus oryzae) 55 4.5 — — — [93] 少孢根霉菌(Rhizopus oligosporus) 55 4.5 — 150 9.47 [94] 微小根毛霉菌(Rhizomucor pusillus) 70 5.4 — — — [95] 嗜热侧孢霉菌(Sporotrichum thermophile) 58 5 — — — [96] 隔孢伏革菌(Peniophora lycii) 50–55 4–4.5 72 100 1080 ± 110 [56] 米曲霉菌(Aspergillus oryzae) 50 5.5 120 330 0.35 [97] 酵母菌 克鲁斯假丝酵母(Candida krusei) 40 2.5, 5.5 330 30 1210 [98] 毕赤酵母菌(Pichia pastoris) 60 2.5, 5.5 95 — 25–65 [99] 异常毕赤酵母菌(Pichia anomala) 60 4 64 200 — [100] 斯巴达克毕赤酵母(Pichia spartinae) 60 2.5 95 — — [25] 西方许旺酵母(Schwanniomyces occidentalis) 70 4.5 70 380 — [25] 酿酒酵母菌(Saccharomyces cerevisiae) 55–60 2–2.5, 5–5.5 120 — 4 [101] 芽殖酵母菌(Saccharomyces castellii) 77 4.4 490 — 0.3–8 [102] 酵母白囊杆菌(Arxula adeninivorans) 75 4.5 — 230 — [31] -

[1] PARK J H, BOLAN N, MEGHARAJ M, et al. Isolation of phosphate solubilizing bacteria and their potential for lead immobilization in soil [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2011, 185(2/3): 829-836. [2] TAURIAN T, ANZUAY M S, ANGELINI J G, et al. Phosphate-solubilizing peanut associated bacteria: Screening for plant growth-promoting activities [J]. Plant and Soil, 2010, 329(1/2): 421-431. [3] BOLAN N S, ADRIANO D C, NAIDU R. Role of phosphorus in (Im)mobilization and bioavailability of heavy metals in the soil-plant system [J]. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2003, 177: 1-44. [4] SINGH B K. Organophosphorus-degrading bacteria: Ecology and industrial applications [J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2009, 7(2): 156-164. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2050 [5] SON H J, PARK G T, CHA M S, et al. Solubilization of insoluble inorganic phosphates by a novel salt- and pH-tolerant Pantoea agglomerans R-42 isolated from soybean rhizosphere [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2006, 97(2): 204-210. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.02.021 [6] GILES C D, HSU P C, RICHARDSON A E, et al. Plant assimilation of phosphorus from an insoluble organic form is improved by addition of an organic anion producing Pseudomonas sp. [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2014, 68: 263-269. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.09.026 [7] HARIPRASAD P, NIRANJANA S R. Isolation and characterization of phosphate solubilizing rhizobacteria to improve plant health of tomato [J]. Plant and Soil, 2009, 316(1/2): 13-24. [8] RICHARDSON A E, HADOBAS P A, HAYES J E. Extracellular secretion of Aspergillus phytase from Arabidopsis roots enables plants to obtain phosphorus from phytate [J]. The Plant Journal: for Cell and Molecular Biology, 2001, 25(6): 641-649. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00998.x [9] NELSON T S, SHIEH T R, WODZINSKI R J, et al. Effect of supplemental phytase on the utilization of phytate phosphorus by chicks [J]. The Journal of Nutrition, 1971, 101(10): 1289-1293. doi: 10.1093/jn/101.10.1289 [10] MANSOTRA P, SHARMA P, SHARMA S. Bioaugmentation of Mesorhizobium Cicer, Pseudomonas spp. and piriformospora indica for sustainable chickpea production [J]. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants, 2015, 21(3): 385-393. doi: 10.1007/s12298-015-0296-0 [11] RICHARDSON A E, SIMPSON R J. Soil microorganisms mediating phosphorus availability update on microbial phosphorus [J]. Plant Physiology, 2011, 156(3): 989-996. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.175448 [12] CREA F, de STEFANO C, MILEA D, et al. Formation and stability of phytate complexes in solution [J]. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2008, 252(10/11): 1108-1120. [13] MULLANEY E J, DALY C B, ULLAH A H. Advances in phytase research [J]. Advances in Applied Microbiology, 2000, 47: 157-199. [14] KUMAR V, SINHA A K, MAKKAR H P S, et al. Dietary roles of phytate and phytase in human nutrition: A review [J]. Food Chemistry, 2010, 120(4): 945-959. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.11.052 [15] FEKRI A, TORBATI M, YARI KHOSROWSHAHI A, et al. Functional effects of phytate-degrading, probiotic lactic acid bacteria and yeast strains isolated from Iranian traditional sourdough on the technological and nutritional properties of whole wheat bread [J]. Food Chemistry, 2020, 306: 125620. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125620 [16] SONG H Y, EL SHEIKHA A F, HU D M. The positive impacts of microbial phytase on its nutritional applications [J]. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 2019, 86: 553-562. doi: 10.1016/j.jpgs.2018.12.001 [17] JORQUERA M, MARTÍNEZ O, MARUYAMA F, et al. Current and future biotechnological applications of bacterial phytases and phytase-producing bacteria [J]. Microbes and Environments, 2008, 23(3): 182-191. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.23.182 [18] PANDEY A, SZAKACS G, SOCCOL C R, et al. Production, purification and properties of microbial phytases [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2001, 77(3): 203-214. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00139-5 [19] GOLOVAN S, WANG G, ZHANG J, et al. Characterization and overproduction of the Escherichia coli appA encoded bifunctional enzyme that exhibits both phytase and acid phosphatase activities [J]. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2000, 46(1): 59-71. doi: 10.1139/cjm-46-1-59 [20] PHILLIPPY B Q, MULLANEY E J. Expression of an Aspergillus niger phytase (phyA) in Escherichia coli [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 1997, 45(8): 3337-3342. doi: 10.1021/jf970276z [21] MULLANEY E J, ULLAH A H J. The term phytase comprises several different classes of enzymes [J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2003, 312(1): 179-184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.176 [22] SHIVANNA G B, GOVINDARAJULU V. Screening of asporogenic mutants of phytase-producing aspergillusniger CFR 335 strain [J]. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, 2009, 21(1): 57-63. doi: 10.1080/08910600902745750 [23] MITCHELL D B, VOGEL K, WEIMANN B J, et al. The phytase subfamily of histidine acid phosphatases: Isolation of genes for two novel phytases from the fungi Aspergillus terreus and Myceliophthora thermophila[J]. Microbiology, 1997, 143 (1): 245-252. [24] OLSTORPE M, SCHNÜRER J, PASSOTH V. Screening of yeast strains for phytase activity [J]. FEMS Yeast Research, 2009, 9(3): 478-488. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00493.x [25] NAKAMURA Y, FUKUHARA H, SANO K. Secreted phytase activities of yeasts [J]. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 2000, 64(4): 841-844. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.841 [26] VOHRA A, SATYANARAYANA T. Phytases: microbial sources, production, purification, and potential biotechnological applications [J]. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 2003, 23(1): 29-60. doi: 10.1080/713609297 [27] RICHARDSON A E, HADOBAS P A. Soil isolates of Pseudomonas spp. that utilize inositol phosphates [J]. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 1997, 43(6): 509-516. doi: 10.1139/m97-073 [28] VOLFOVÁ O, DVOŘÁKOVÁ J, HANZLÍKOVÁ A, et al. Phytase from Aspergillus niger [J]. Folia Microbiologica, 1994, 39(6): 481-484. doi: 10.1007/BF02814066 [29] GARGOVA S, ROSHKOVA Z, VANCHEVA G. Screening of fungi for phytase production [J]. Biotechnology Techniques, 1997, 11(4): 221-224. doi: 10.1023/A:1018426119073 [30] LAMBRECHTS C, BOZE H, MOULIN G, et al. Utilization of phytate by some yeasts [J]. Biotechnology Letters, 1992, 14(1): 61-66. doi: 10.1007/BF01030915 [31] SANO K, FUKUHARA H, NAKAMURA Y. Phytase of the yeast Arxula adeninivorans [J]. Biotechnology Letters, 1999, 21(1): 33-38. doi: 10.1023/A:1005438121763 [32] BAE H D, YANKE L J, CHENG K J, et al. A novel staining method for detecting phytase activity [J]. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 1999, 39(1): 17-22. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(99)00096-2 [33] ENGELEN A J, van der HEEFT F C, RANDSDORP P H G, et al. Simple and rapid determination of phytase activity [J]. Journal of AOAC INTERNATIONAL, 2020, 77(3): 760-764. [34] VATS P, BANERJEE U C. Production studies and catalytic properties of phytases (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate phosphohydrolases): An overview [J]. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 2004, 35(1): 3-14. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2004.03.010 [35] PANDEY A, SOCCOL C R. Bioconversion of biomass: A case study of ligno-cellulosics bioconversions in solid state fermentation [J]. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 1998, 41(4): 379-390. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89131998000400001 [36] PANDEY A, SOCCOL C R, MITCHELL D. New developments in solid state fermentation: I-bioprocesses and products [J]. Process Biochemistry, 2000, 35(10): 1153-1169. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(00)00152-7 [37] PANDEY A, SOCCOL C. Economic utilization of crop residues for value addition: A futuristic approach [J]. Journal of Scientific and Industrial Research, 2000, 59(1): 12-22. [38] HAN Y W, GALLAGHER D J, WILFRED A G. Phytase production by Aspergillus ficuum on semisolid substrate [J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology, 1987, 2(4): 195-200. doi: 10.1007/BF01569540 [39] PAPAGIANNI M, NOKES S E, FILER K. Production of phytase by Aspergillus niger in submerged and solid-state fermentation [J]. Process Biochemistry, 1999, 35(3/4): 397-402. [40] SAJIDAN A, FAROUK A, GREINER R, et al. Molecular and physiological characterisation of a 3-phytase from soil bacterium Klebsiella sp. ASR1 [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2004, 65(1): 110-118. [41] SREERAMULU G, SRINIVASA D S, NAND K, et al. Lactobacillus amylovorus as a phytase producer in submerged culture [J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 1996, 23(6): 385-388. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1996.tb01342.x [42] YANKE L J, BAE H D, SELINGER L B, et al. Phytase activity of anaerobic ruminal bacteria[J]. Microbiology , 1998, 144 ( 6): 1565-1573. [43] LAN G Q, ABDULLAH N, JALALUDIN S, et al. Culture conditions influencing phytase production of Mitsuokella jalaludinii, a new bacterial species from the rumen of cattle [J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2002, 93(4): 668-674. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01727.x [44] HERTER T, BEREZINA O V, ZININ N V, et al. Glucose-1-phosphatase (AgpE) from Enterobacter cloacae displays enhanced phytase activity [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2006, 70(1): 60-64. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0024-8 [45] YOON S J, CHOI Y J, MIN H K, et al. Isolation and identification of phytase-producing bacterium, Enterobacter sp. 4, and enzymatic properties of phytase enzyme [J]. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 1996, 18(6): 449-454. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(95)00131-X [46] TAMBE S M, KAKLIJ G S, KELKAR S M, et al. Two distinct molecular forms of phytase from Klebsiella aerogenes: Evidence for unusually small active enzyme peptide [J]. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering, 1994, 77(1): 23-27. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(94)90202-X [47] WANG X Y, UPATHAM S, PANBANGRED W, et al. Purification, characterization, gene cloning and sequence analysis of a phytase from Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae XY-5 [J]. ScienceAsia, 2004, 30: 383-390. doi: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2004.30.383 [48] GREINER R, HALLER E, KONIETZNY U, et al. Purification and characterization of a phytase from Klebsiella terrigena [J]. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 1997, 341(2): 201-206. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9942 [49] JAREONKITMONGKOL S, OHYA M, WATANABE R, et al. Partial purification of phytase from a soil isolate bacterium, Klebsiella oxytoca MO-3 [J]. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering, 1997, 83(4): 393-394. doi: 10.1016/S0922-338X(97)80149-3 [50] ZININ N V, SERKINA A V, GELFAND M S, et al. Gene cloning, expression and characterization of novel phytase from Obesumbacterium proteus [J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2004, 236(2): 283-290. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09659.x [51] GREINER R. Purification and properties of a phytate-degrading enzyme from Pantoea agglomerans [J]. The Protein Journal, 2004, 23(8): 567-576. doi: 10.1007/s10930-004-7883-1 [52] VASHISHTH A, RAM S, BENIWAL V. Cereal phytases and their importance in improvement of micronutrients bioavailability [J]. 3 Biotech, 2017, 7(1): 42. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0698-5 [53] CHO J, LEE C, KANG S, et al. Molecular cloning of a phytase gene (phy M) from Pseudomonas syringae MOK1 [J]. Current Microbiology, 2005, 51(1): 11-15. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-4482-0 [54] IN M J, JANG E S, KIM Y, et al. Purification and properties of an extracellular acid phytase from Pseudomonas fragi Y9451 [J]. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2004, 14(5): 1004-1008. [55] HUANG H Q, LUO H Y, YANG P L, et al. A novel phytase with preferable characteristics from Yersinia intermedia [J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2006, 350(4): 884-889. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.118 [56] GEORGE T S, SIMPSON R J, GREGORY P J, et al. Differential interaction of Aspergillus niger and Peniophora lycii phytases with soil particles affects the hydrolysis of inositol phosphates [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2007, 39(3): 793-803. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.09.029 [57] SHIEH T R, WARE J H. Survey of microorganism for the production of extracellular phytase [J]. Applied Microbiology, 1968, 16(9): 1348-1351. doi: 10.1128/am.16.9.1348-1351.1968 [58] VATS P, BANERJEE U C. Biochemical characterisation of extracellular phytase (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate phosphohydrolase) from a hyper-producing strain of Aspergillus niger van Teighem [J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2005, 32(4): 141-147. doi: 10.1007/s10295-005-0214-5 [59] HA N C, KIM Y O, OH T K, et al. Preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of a novel phytase from a strain [J]. Acta Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography, 1999, 55(3): 691-693. doi: 10.1107/S0907444998015285 [60] TYE A, SIU F, LEUNG T, et al. Molecular cloning and the biochemical characterization of two novel phytases from B. subtilis168 and B. licheniformis [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2002, 59(2/3): 190-197. [61] KEROVUO J, LAURAEUS M, NURMINEN P, et al. Isolation, characterization, molecular gene cloning, and sequencing of a novel phytase from Bacillus subtilis [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1998, 64(6): 2079-2085. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.6.2079-2085.1998 [62] KIM Y O, LEE J K, KIM H K, et al. Cloning of the thermostable phytase gene (phy) from Bacillus sp. DS11 and its overexpression in Escherichia coli [J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 1998, 162(1): 185-191. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12997.x [63] KIM H W, KIM Y O, LEE J H, et al. Isolation and characterization of a phytase with improved properties from Citrobacter braakii [J]. Biotechnology Letters, 2003, 25(15): 1231-1234. doi: 10.1023/A:1025020309596 [64] PAYNTER M J, ELSDEN S R. Mechanism of propionate formation by Selenomonas ruminantium, a rumen micro-organism [J]. Journal of General Microbiology, 1970, 61(1): 1-7. doi: 10.1099/00221287-61-1-1 [65] IRVING G, COSGROVE D J. Inositol phosphate phosphatases of microbiological origin. some properties of a partially purified bacterial (Pseudomonas sp. ) phytase [J]. Australian Journal of Biological Sciences, 1971, 24(3): 547. doi: 10.1071/BI9710547 [66] LI R J, LU W J, GUO C J, et al. Molecular characterization and functional analysis of OsPHY1, a purple acid phosphatase (PAP)-type phytase gene in rice (Oryza sativa L. ) [J]. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 2012, 11(8): 1217-1226. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(12)60118-X [67] IDRISS E E, MAKAREWICZ O, FAROUK A, et al. Extracellular phytase activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB45 contributes to its plant-growth-promoting effect[J]. Microbiology , 2002, 148(7): 2097-2109. [68] POWAR V K, JAGANNATHAN V. Purification and properties of phytate-specific phosphatase from Bacillus subtilis [J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 1982, 151(3): 1102-1108. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.3.1102-1108.1982 [69] KUMAR V, SANGWAN P, VERMA A K, et al. Molecular and biochemical characteristics of recombinant β-propeller phytase from Bacillus licheniformis strain PB-13 with potential application in aquafeed [J]. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2014, 173(2): 646-659. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-0871-9 [70] CHOI Y M, SUH H J, KIM J M. Purification and properties of extracellular phytase from Bacillus sp. KHU-10 [J]. Journal of Protein Chemistry, 2001, 20(4): 287-292. doi: 10.1023/A:1010945416862 [71] GREINER R, KONIETZNY U, JANY K D. Purification and characterization of two phytases from Escherichia coli [J]. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 1993, 303(1): 107-113. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1261 [72] GREINER R, CARLSSON N G. Myo-Inositol phosphate isomers generated by the action of a phytate-degrading enzyme from Klebsiella terrigena on phytate [J]. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2006, 52(8): 759-768. doi: 10.1139/w06-028 [73] GREINER R. Degradation of myo-inositol hexakisphosphate by a phytate-degrading enzyme from Pantoea agglomerans [J]. The Protein Journal, 2004, 23(8): 577-585. doi: 10.1007/s10930-004-7884-0 [74] GREINER R, FAROUK A, ALMINGER M L, et al. The pathway of dephosphorylation of myo-inositol hexakisphosphate by phytate-degrading enzymes of different Bacillus spp. [J]. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2002, 48(11): 986-994. doi: 10.1139/w02-097 [75] PALACIOS M C, HAROS M, ROSELL C M, et al. Characterization of an acid phosphatase from Lactobacillus pentosus: Regulation and biochemical properties [J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2005, 98(1): 229-237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02447.x [76] ZAMUDIO M, GONZÁLEZ A, MEDINA J A. Lactobacillus plantarum phytase activity is due to non-specific acid phosphatase [J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2001, 32(3): 181-184. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2001.00890.x [77] YANKE L J, SELINGER L B, CHENG K J. Phytase activity of Selenomonas ruminantium: A preliminary characterization [J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 1999, 29(1): 20-25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00568.x [78] SHAH V, PAREKH L J. Phytase from Klebsiella sp. No. PG–2: Purification and properties [J]. Indian Journal of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 1990, 27(2): 98-102. [79] LASSEN S F, BREINHOLT J, ØSTERGAARD P R, et al. Expression, gene cloning, and characterization of five novel phytases from four basidiomycete fungi: Peniophora lycii,Agrocybe pediades, a Ceriporia sp., and Trametes pubescens [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2001, 67(10): 4701-4707. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4701-4707.2001 [80] SHANKS R M Q, DASHIFF A, ALSTER J S, et al. Isolation and identification of a bacteriocin with antibacterial and antibiofilm activity from Citrobacter freundii [J]. Archives of Microbiology, 2012, 194(7): 575-587. doi: 10.1007/s00203-012-0793-2 [81] LI C, LIN Y, ZHENG X Y, et al. Combined strategies for improving expression of Citrobacter amalonaticus phytase in Pichia pastoris [J]. BMC Biotechnology, 2015, 15: 88. doi: 10.1186/s12896-015-0204-2 [82] BERKA R M, REY M W, BROWN K M, et al. Molecular characterization and expression of a phytase gene from the thermophilic fungus Thermomyces lanuginosus [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1998, 64(11): 4423-4427. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.11.4423-4427.1998 [83] WYSS M, PASAMONTES L, FRIEDLEIN A, et al. Biophysical characterization of fungal phytases (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate phosphohydrolases): Molecular size, glycosylation pattern, and engineering of proteolytic resistance [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1999, 65(2): 359-366. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.2.359-366.1999 [84] FU S J, SUN J Y, QIAN L C, et al. Bacillus phytases: Present scenario and future perspectives [J]. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2008, 151(1): 1-8. doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8158-7 [85] GU W N, HUANG H Q, MENG K, et al. Gene cloning, expression, and characterization of a novel phytase from Dickeya paradisiaca [J]. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2009, 157(2): 113-123. doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8329-6 [86] de ANGELIS M, GALLO G, CORBO M R, et al. Phytase activity in sourdough lactic acid bacteria: Purification and characterization of a phytase from Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis CB1 [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2003, 87(3): 259-270. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00072-2 [87] AL-ASHEH S, DUVNJAK Z. Characteristics of phytase produced by Aspergillus carbonarius NRC 401121 in canola meal [J]. Acta Biotechnologica, 1994, 14(3): 223-233. doi: 10.1002/abio.370140302 [88] XIANG T, LIU Q, DEACON A M, et al. Crystal structure of a heat-resilient phytase from Aspergillus fumigatus, carrying a phosphorylated histidine [J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 2004, 339(2): 437-445. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.057 [89] RIBEIRO CORRÊA T L, de QUEIROZ M V, de ARAÚJO E F. Cloning, recombinant expression and characterization of a new phytase from Penicillium chrysogenum [J]. Microbiological Research, 2015, 170: 205-212. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2014.06.005 [90] TSENG Y H, FANG T J, TSENG S M. Isolation and characterization of a novel phytase from Penicillium simplicissimum [J]. Folia Microbiologica, 2000, 45(2): 121-127. doi: 10.1007/BF02817409 [91] LEE J, CHOI Y, LEE P C, et al. Recombinant production of Penicillium oxalicum PJ3 phytase in Pichia pastoris [J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2007, 23(3): 443-446. doi: 10.1007/s11274-006-9236-z [92] QUAN C S, TIAN W J, FAN S D, et al. Purification and properties of a low-molecular-weight phytase from Cladosporium sp. FP-1 [J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2004, 97(4): 260-266. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(04)70201-7 [93] RAMACHANDRAN S, ROOPESH K, NAMPOOTHIRI K M, et al. Mixed substrate fermentation for the production of phytase byRhizopus spp. using oilcakes as substrates [J]. Process Biochemistry, 2005, 40(5): 1749-1754. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2004.06.040 [94] JIN U H, CHUN J A, LEE J W, et al. Expression and characterization of extracellular fungal phytase in transformed sesame hairy root cultures [J]. Protein Expression and Purification, 2004, 37(2): 486-492. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.06.020 [95] BOYCE A, WALSH G. Purification and characterisation of an acid phosphatase with phytase activity from Mucor hiemalis Wehmer [J]. Journal of Biotechnology, 2007, 132(1): 82-87. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.08.028 [96] SINGH B, SATYANARAYANA T. Improved phytase production by a thermophilic mould Sporotrichum thermophile in submerged fermentation due to statistical optimization [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2008, 99(4): 824-830. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.01.007 [97] SHIMIZU M. Purification and characterization of phytase and acid phosphatase produced by Aspergillus oryzae K1 [J]. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 1993, 57(8): 1364-1365. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1364 [98] QUAN C S, FAN S D, ZHANG L H, et al. Purification and properties of a phytase from Candida krusei WZ-001 [J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2002, 94(5): 419-425. [99] HAN Y M, LEI X G. Role of glycosylation in the functional expression of an Aspergillus niger Phytase (phyA) in Pichia pastoris [J]. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 1999, 364(1): 83-90. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1115 [100] HELLSTRÖM A M, VÁZQUES-JUÁREZ R, SVANBERG U, et al. Biodiversity and phytase capacity of yeasts isolated from Tanzanian togwa [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2010, 136(3): 352-358. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.10.011 [101] HARALDSSON A K, VEIDE J, ANDLID T, et al. Degradation of phytate by high-phytase Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains during simulated gastrointestinal digestion [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2005, 53(13): 5438-5444. doi: 10.1021/jf0478399 [102] SEGUEILHA L, LAMBRECHTS C, BOZE H, et al. Purification and properties of the phytase from Schwanniomyces castellii [J]. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering, 1992, 74(1): 7-11. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(92)90259-W [103] LIM B L, YEUNG P, CHENG C W, et al. Distribution and diversity of phytate-mineralizing bacteria [J]. The ISME Journal, 2007, 1(4): 321-330. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.40 [104] ROCKY-SALIMI K, HASHEMI M, SAFARI M, et al. A novel phytase characterized by thermostability and high pH tolerance from rice phyllosphere isolated Bacillus subtilis B. S. 46 [J]. Journal of Advanced Research, 2016, 7(3): 381-390. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2016.02.003 [105] MUKHAMETZIANOVA A D, AKHMETOVA A I, SHARIPOVA M R. Microorganisms as phytase producers [J]. Mikrobiologiia, 2012, 81(3): 291-300. [106] YAO M Z, ZHANG Y H, LU W L, et al. Phytases: crystal structures, protein engineering and potential biotechnological applications [J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2012, 112(1): 1-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05181.x [107] BALWANI I, CHAKRAVARTY K, GAUR S. Role of phytase producing microorganisms towards agricultural sustainability [J]. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 2017, 12: 23-29. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2017.08.010 [108] CHEN C R, CONDRON L M, DAVIS M R, et al. Phosphorus dynamics in the rhizosphere of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L. ) and radiata pine (Pinus radiata D. Don. ) [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2002, 34(4): 487-499. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00207-3 [109] BÜNEMANN E K. Enzyme additions as a tool to assess the potential bioavailability of organically bound nutrients [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2008, 40(9): 2116-2129. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.03.001 [110] TARAFDAR J C, YADAV R S, MEENA S C. Comparative efficiency of acid phosphatase originated from plant and fungal sources [J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 2001, 164(3): 279-282. doi: 10.1002/1522-2624(200106)164:3<279::AID-JPLN279>3.0.CO;2-L [111] JORQUERA M A, CROWLEY D E, MARSCHNER P, et al. Identification of β-propeller phytase-encoding genes in culturable Paenibacillus and Bacillus spp. from the rhizosphere of pasture plants on volcanic soils [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2011, 75(1): 163-172. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00995.x [112] BOHN L, MEYER A S, RASMUSSEN S K. Phytate: impact on environment and human nutrition. A challenge for molecular breeding [J]. Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B, 2008, 9(3): 165-191. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0710640 [113] QUIQUAMPOIX H, BURNS R G. Interactions between proteins and soil mineral surfaces: Environmental and health consequences [J]. Elements, 2007, 3(6): 401-406. doi: 10.2113/GSELEMENTS.3.6.401 [114] WALLENSTEIN M, ALLISON S D, ERNAKOVICH J, et al. Controls on the temperature sensitivity of soil enzymes: A key driver of in situ enzyme activity rates [J].Soil Enzymology, 2011: 245–258. [115] FAROUK A E A, GREINER R, HUSSIN A S M. Purification and properties of a phytate-degrading enzyme produced by Enterobacter sakazakii ASUIA279 [J]. Journal of Biotechnology and Biodiversity, 2012, 3(1): 1-9. [116] ESCOBIN-MOPERA L, OHTANI M, SEKIGUCHI S, et al. Purification and characterization of phytase from Klebsiella pneumoniae 9-3B [J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2012, 113(5): 562-567. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.12.010 [117] SREEDEVI S, REDDY B N. Purification and biochemical characterization of phytase from newly isolated Bacillus subtilis C43 [J]. Advanced Biotechnology, 2013, 12(8): 52-60. [118] KONIETZNY U, GREINER R. Molecular and catalytic properties of phytate-degrading enzymes (phytases) [J]. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2002, 37(7): 791-812. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2621.2002.00617.x [119] EL-TOUKHY N M K, YOUSSEF A S, MIKHAIL M. Isolation, purification and characterization of phytase from Bacillus subtilis MJA [J]. African Journal of Biotechnology, 2013, 12: 2957-2967. [120] WYSS M, BRUGGER R, KRONENBERGER A, et al. Biochemical characterization of fungal phytases (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate phosphohydrolases): Catalytic properties [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1999, 65(2): 367-373. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.2.367-373.1999 [121] MARLIDA Y, DELFITA R, ADNADI P, et al. Isolation, characterization and production of phytase from endophytic fungus its application for feed [J]. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 2010, 9(5): 471-474. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2010.471.474 [122] CRAINE J M, FIERER N, MCLAUCHLAN K K. Widespread coupling between the rate and temperature sensitivity of organic matter decay [J]. Nature Geoscience, 2010, 3(12): 854-857. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1009 [123] KOCH O, TSCHERKO D, KANDELER E. Temperature sensitivity of microbial respiration, nitrogen mineralization, and potential soil enzyme activities in organic alpine soils [J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 2007, 21(4): 1-11. [124] WALLENSTEIN M D, MCMAHON S K, SCHIMEL J P. Seasonal variation in enzyme activities and temperature sensitivities in Arctic tundra soils [J]. Global Change Biology, 2009, 15(7): 1631-1639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01819.x [125] LONHIENNE T, GERDAY C, FELLER G. Psychrophilic enzymes: Revisiting the thermodynamic parameters of activation may explain local flexibility [J]. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology, 2000, 1543(1): 1-10. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4838(00)00210-7 [126] FELLER G. Molecular adaptations to cold in psychrophilic enzymes [J]. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences:CMLS, 2003, 60(4): 648-662. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2155-3 [127] JOHNSON S C, YANG M M, MURTHY P P N. Heterologous expression and functional characterization of a plant alkaline phytase in Pichia pastoris [J]. Protein Expression and Purification, 2010, 74(2): 196-203. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2010.07.003 [128] KONIETZNY U, GREINER R. Bacterial phytase: Potential application, in vivo function and regulation of its synthesis [J]. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 2004, 35(1/2): 12-18. [129] GEORGE T S, RICHARDSON A E, SIMPSON R J. Behaviour of plant-derived extracellular phytase upon addition to soil [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2005, 37(5): 977-988. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.10.016 [130] BOGAR B, SZAKACS G, LINDEN J C, et al. Optimization of phytase production by solid substrate fermentation [J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2003, 30(3): 183-189. doi: 10.1007/s10295-003-0027-3 [131] TANG J, LEUNG A, LEUNG C, et al. Hydrolysis of precipitated phytate by three distinct families of phytases [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2006, 38(6): 1316-1324. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.08.021 [132] ADAMS M A, PATE J S. Availability of organic and inorganic forms of phosphorus to lupins (Lupinus spp. ) [J]. Plant and Soil, 1992, 145(1): 107-113. doi: 10.1007/BF00009546 [133] RAO M A, VIOLANTE A, GIANFREDA L. Interaction of acid phosphatase with clays, organic molecules and organo-mineral complexes: Kinetics and stability [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2000, 32(7): 1007-1014. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00010-9 期刊类型引用(7)

1. 张俐敏,刘天一,刘文佳,徐畅,莫继先. 植酸酶微胶囊酶制剂的研发及其植物促生作用研究. 农业生物技术学报. 2025(02): 427-442 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 姚卫格,樊丽,孙蕊,康杰,葛菁萍. 细胞外囊泡在农业与环境保护中的作用研究进展. 中国农学通报. 2025(06): 88-93 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 姚卫格,刘磊,孙蕊,康杰,葛菁萍. 添加乙酸对Saccharomyces cerevisiae L7增产2, 3-丁二醇的机理探究. 黑龙江大学自然科学学报. 2025(01): 56-62 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 李江涛,鲁芳,王思齐,张一彤,任养杰,国世阳,王奔,高伟. 双功能域β-折叠桶植酸酶提高土壤有效磷含量研究. 中国土壤与肥料. 2024(02): 27-32 .  百度学术

百度学术

5. 黄诗蔚,张子颖,钟小琳,江钧,朱锋,蒋逸凡,张雨菲,薛生国. 酸浸米糠协同脱硫石膏驱动赤泥成土. 中国有色金属学报. 2024(05): 1712-1726 .  百度学术

百度学术

6. 李小林,高乾程,刘雨星,王相平,张俊华,姚荣江. 盐分梯度对土壤中不同磷素形态转化的影响. 土壤. 2024(06): 1222-1230 .  百度学术

百度学术

7. 廖远行,舒英格,王昌敏,蔡华,李雪梅,罗秀龙,龙慧. 喀斯特地区不同植被类型土壤微生物量磷、碱性磷酸酶及植酸酶的变化特征. 南方农业学报. 2023(06): 1762-1770 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(6)

-

下载:

下载: