-

药品及个人护理用品(pharmaceutical and personal care products,PPCPs)是水环境普遍存在的新型污染物,其中药品包括抗生素、激素、止痛药、消炎药、β-阻滞剂等。个人护理产品包括防腐剂、杀菌剂/消毒剂、驱虫剂、防晒剂、香水等[1-2]。污水处理厂出水排放是PPCPs进入水环境的主要途径之一[3-4]。尽管污水中PPCPs浓度不高(ng L−1—μg L−1),但PPCPs长期暴露会对生态环境[5]和人体健康[6-7]产生不利影响,因此提高污水中PPCPs的去除效果是急需解决的问题。

活性污泥和生物膜法是最常用的两种污水处理工艺,主要为去除碳氮磷等常规水污染物设计,无法完全去除PPCPs等新型污染物。污水处理过程PPCPs的迁移转化机制复杂[8],且去除效果与污水处理工艺条件、运行参数、水质参数等多种因素密切相关[9-10],采用实验优化难以获取最佳去除效果的参数组合[11]。数学模型是预测并精准调控复杂条件下污染物去除规律的重要手段。国际水协会(Intemational Water Association,IWA)于1986年起相继推出活性污泥1、2、2D、3号模型和生物膜一维、二维、三维模型[12-17],这两种工艺模型利用矩阵表达系统中涉及的关键组分和过程,通过定量描述与物质降解、微生物生长等过程相关的动力学和化学计量系数,解释系统内部的各个主要活动,并能外推出其他实验条件下的过程,进行更有效的实验设计。活性污泥和生物膜模型已广泛应用于预测碳氮磷等传统物质的去除。随着污水中PPCPs等新型污染物的不断增加及其潜在的不利影响,如何修改和扩展已有的活性污泥和生物膜模型以强化PPCPs在污水中的去除引起了国内外研究者们的广泛关注。Plósz等[18]提出可用于评价外源痕量物质去除的活性污泥模型(ASM-X),该模型仅包括液相中母体化合物和可逆转化化合物以及固相中的吸附化合物三个组分,不考虑其余可溶性化合物和生物量组分。ASM-X能够预测PPCPs及其转化产物在污水中的浓度变化,但该模型无法解释PPCPs降解机制,也无法优化PPCPs去除条件。

如何在原有模型基础上研发适用于预测并强化污水中PPCPs去除的数学模型是今后研究的重要方向。PPCPs去除模型的建立可以解决污水中PPCPs难以定量的问题,准确预测出水中PPCPs及其转化产物在不同条件下的浓度变化,并深入探究PPCPs在生物处理系统中的微生物降解性能、降解机制和主要限速因素,模拟不同运行参数对去除效果的影响,从而获得最有利于PPCPs去除的污水处理工艺参数组合。本文综述了PPCPs去除模型在评价不同微生物降解性能,探究PPCPs生物降解机制及限制因素,以及优化PPCPs去除参数方面的应用,为精准调控污水中PPCPs去除提供参考。

-

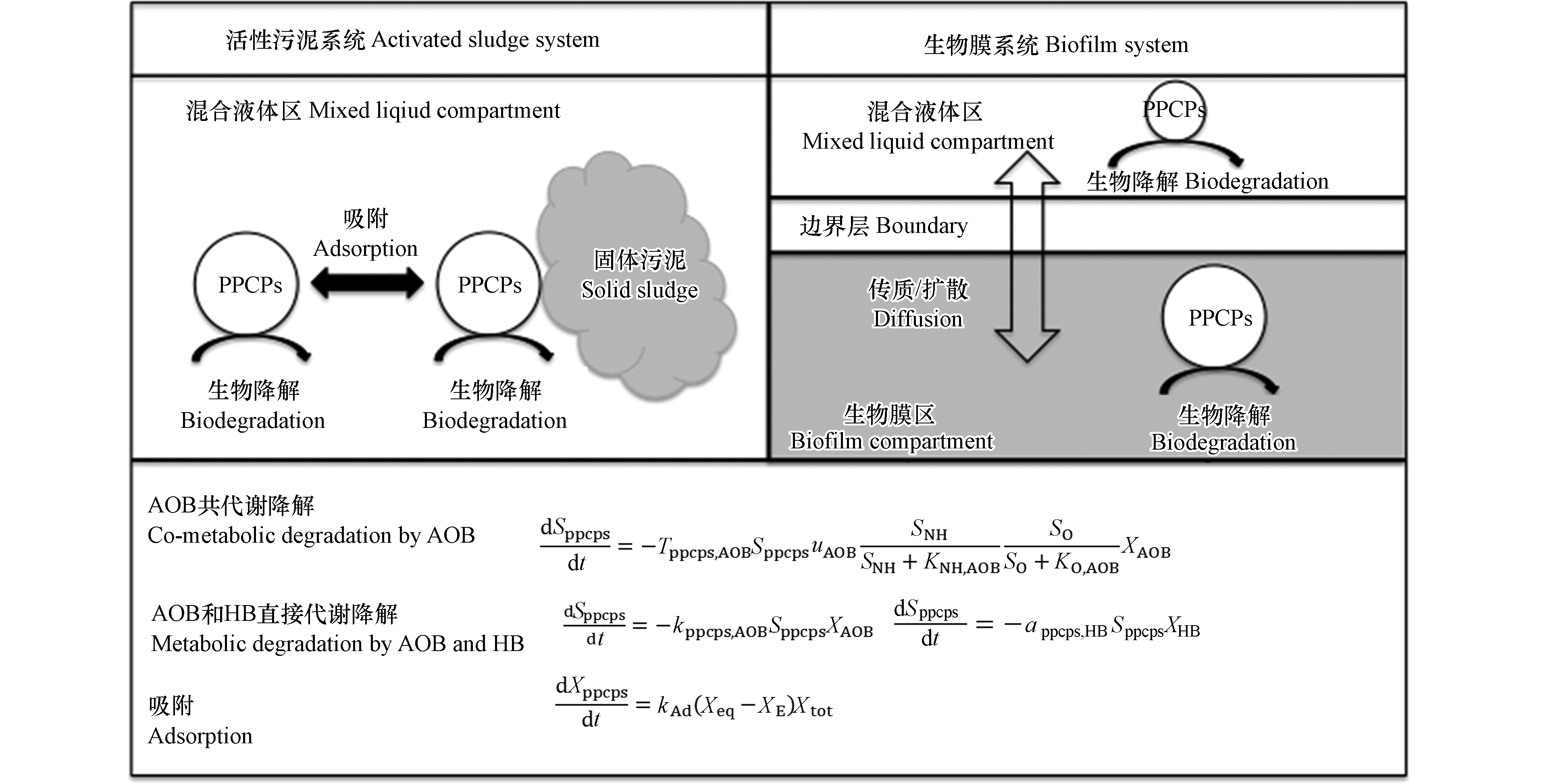

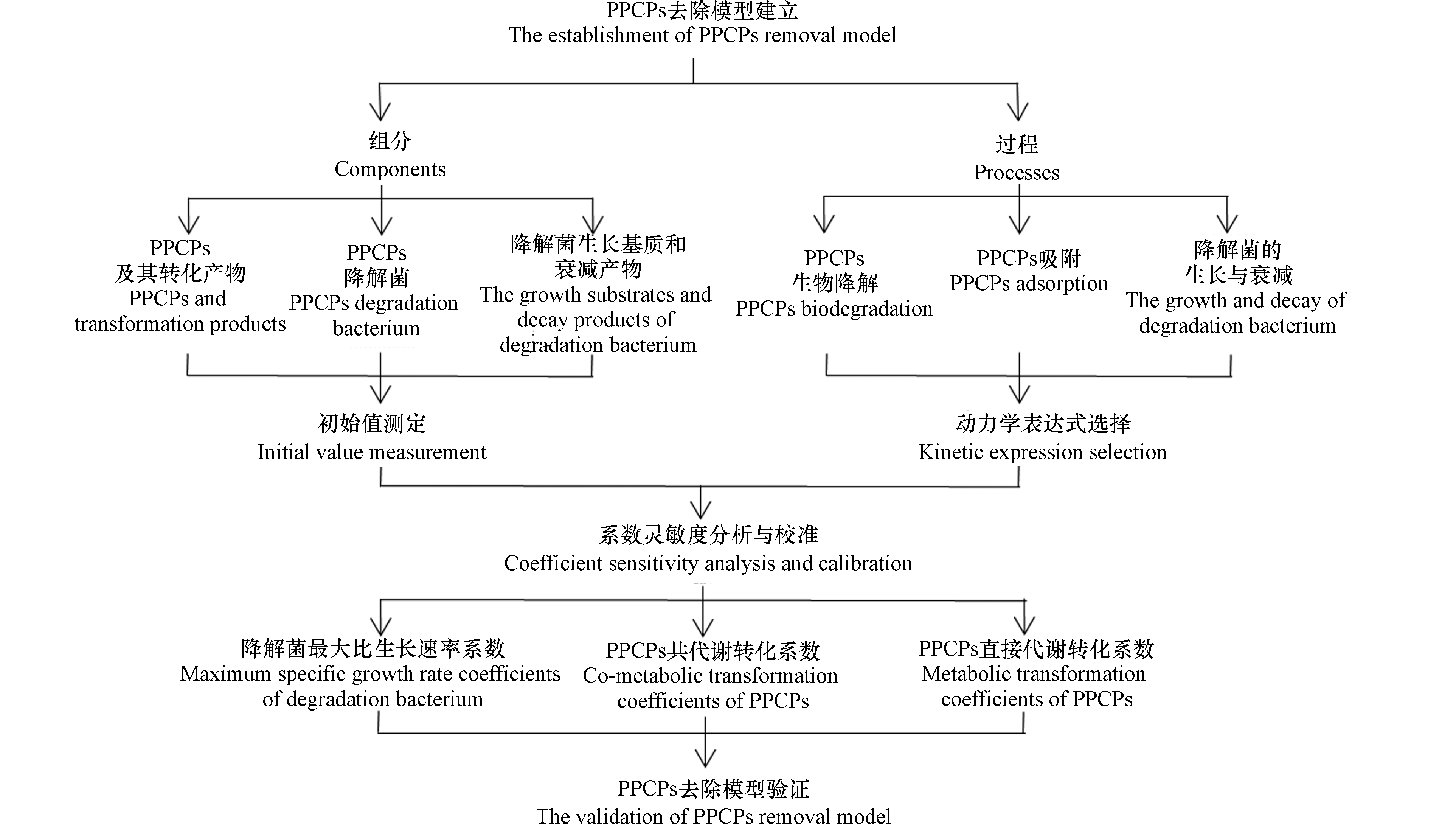

活性污泥和生物膜模型多用于预测碳氮磷等常规水污染物的去除。PPCPs的加入会使原有体系中的微生物活动发生变化,原始模型结构和动力学表达无法准确预测PPCPs的去除,因此必须根据PPCPs的去除规律对模型进行修正,并重新定义和校准影响PPCPs去除的动力学和化学计量系数。图1给出了PPCPs去除模型的建立步骤。

-

模型中的关键组分可大致分为四类:微生物、底物、衰减产物和溶解氧。在PPCPs去除模型中,对PPCPs具有生物降解作用的微生物(氨氧化细菌、异养细菌等)是模型中最关键的微生物组分。此外亚硝酸盐氧化细菌(nitrite oxidizing bacteria,NOB)是硝化反应的重要参与者,也是PPCPs去除模型必不可少的微生物组分。与这些微生物生长代谢相关的底物是模型中关键的物质组分。除碳、氮等生长底物外,PPCPs及其转化产物通常由微生物直接代谢或共代谢去除,因此PPCPs及其转化产物必须纳入模型组分。可溶性微生物产物和胞外聚合物作为微生物的生长底物和衰减产物,影响微生物交互和物质利用等过程,也是模型中常见的物质组分[19-21]。溶解氧是活性污泥和生物膜工艺得以运行的关键条件,也是PPCPs去除模型的关键组分[19]。

进水COD和生物量组分的定量是目前模型应用的主要挑战之一。呼吸速率法与微生物生长代谢直接相关,能够提供更多关于微生物生长和物质降解的信息,广泛应用于模型研究[22-23],是活性污泥和生物膜体系中最常用的进水COD组分表征方法,即根据耗氧速率(OUR)的变化计算不同COD组分浓度[24-26]。硝化细菌和异养细菌是PPCPs生物降解的主要微生物,对这两种微生物定量是提高模型预测准确性的关键。传统的生物量测定方法包括平板计数法和MPN计数法[27],或用混合液悬浮固体(MLSS)来代替生物量[28]。此类方法误差大,不利于模型的准确预测。近年来,荧光原位杂交技术(FISH)、流式细胞术(FCM)、聚合酶链反应(PCR)、高通量测序(HTS)等分子技术[29-32]在微生物定量中发挥了重要作用。然而,由于操作过程复杂且耗时长,以及所需的特殊设备和高昂的维护成本,分子技术很少用于实际污水处理的管理和操作。用于微生物定量的呼吸速率法包括指数生长法、内源呼吸速率法和最大比呼吸速率法[33]。其中内源呼吸法凭借过程稳定、测定指标少等优点,在模型建立中应用更广泛。

模型最基础的过程是微生物利用不同生长底物的生长和衰减过程。PPCPs去除过程的确定则与PPCPs性质密切相关,对于双氯芬酸、卡马西平等强吸附PPCPs来说,吸附和脱附过程是模型中的关键过程[34]。而对于吸附可忽略的PPCPs来说,不同微生物对PPCPs的不同代谢途径是模型的关键过程,主要包括氨氧化细菌(ammonia oxidizing bacteria,AOB)和异养细菌(heterotrophic bacteria,HB)对PPCPs的共代谢和直接代谢两种途径。产物PPCPs逆转化为母体PPCPs也是PPCPs去除模型的关键过程,用于研究逆转化过程对模型预测结果的影响[35-36]。

-

组分和过程确定后,模型的基本架构得以建立,需选择合适的动力学表达式准确描述PPCPs的去除过程。最简便的动力学表达式是伪一阶方程,即认为PPCPs的生物降解和吸附仅与PPCPs和生物量浓度有关[37-39]。在PPCPs浓度极低且生物量浓度基本稳定的条件下,伪一阶动力学可以描述PPCPs的去除[40-42]。另外PPCPs生物降解是一种酶促反应,还可以用Michaelis-Menten动力学描述[43-44],有研究发现Michaelis-Menten动力学准确性不如伪一阶动力学,可能因为酶的活性不是影响PPCPs生物降解的主要因素[8]。

伪一阶动力学和Michaelis-Menten动力学无法解释PPCPs生物降解机制及其与污水基质的关系,因为这两种动力学不区分微生物对PPCPs不同的降解过程,不包含影响PPCPs生物降解的各项因素。Monod方程将影响微生物生长代谢的操作参数和基质浓度作为开关函数引入表达式,例如溶解氧(SO)、溶解性可生物降解基质(SS)[19]、碳氮比[27]等。Monod动力学在揭示PPCPs共代谢机制方面发挥了重要作用,在活性污泥和生物膜模型中应用更广泛。Su等[27]比较了Logistic动力学和Monod动力学在活性污泥模型中的预测精度。Logistic动力学以1/(1+eX)形式表达,其中X包括各过程中的影响因子。研究发现Logistic动力学的预测结果与实验值更接近,且对细微变化的反应更灵敏。这可能是因为Logistic动力学包含的参数更多,但同时增加了模型建立的复杂性。表1列举了不同类型PPCPs在不同处理工艺中适用的降解动力学表达式。

动力学表达式包含了许多系数,有两类系数无须估测,可直接采用默认值,一是不会随污水水质的不同而有显著变化的系数,如自养菌产率系数YA、自养菌衰减系数bA等;二是起到开关函数的作用,取值对结果影响不大的系数,如异养菌和自养菌的氧半饱和系数KO, H、KO, A等。但另外一些系数依赖于污水水质、微生物结构等诸多因素,且对模型预测结果有很大影响,需要实际测定与校准。敏感性分析的目的是研究模型系数误差大小对模型预测结果的影响,从而筛选关键系数[58]。每种PPCPs都具有一组特定的高敏感度系数集,对这组高敏感度系数集的校准是提高模型预测准确性的关键。在大多数与PPCPs去除模型相关的研究中,与降解菌生长速率(uAOB、uHB)和PPCPs生物转化(TAOB、kAOB等)相关的系数对预测结果的影响最大[49,59]。这些关键系数可以通过呼吸速率法直接测定[60-61],但更多情况下通过拟合水质指标的实测值和模拟值进行校准,即最小化实测值和模拟值的均方根误差(RMSE)、和方差(SSE)或相对误差(RE)等指标[21,56]。另外,这些系数受到多种运行参数(如pH和温度)的影响,因此在PPCPs去除过程中保持pH在中性范围且基本恒定是很有必要的,同时可用修正后的Arrhenius公式来描述温度与系数的关系,提出不同的温度校正因子[62-64]。系数的敏感性分析和校准可通过Aquasim、MATLAB等软件进行分析。

-

生物膜模型与活性污泥模型采用一致的矩阵表达形式,建模流程大体相似,且生物膜体系和活性污泥体系中PPCPs的去除机制都为吸附和生物降解去除,因此生物膜模型和活性污泥模型可采用一致的动力学表达公式。图2列举了这两种模型中PPCPs由不同途径去除的动力学方程。但由于生物膜体系所涉及的物质流动更加复杂,因此建立PPCPs生物膜去除模型需要对更多过程和参数进行定量描述。

生物膜体系中存在的传质现象和生物量的分离,一直是生物膜模型建立的难点[65]。模型建立时需要对反应区域进行分块。如图2所示,在活性污泥模型中,PPCPs和其它物质可假定都在液相中被生物降解,而生物膜模型的区域划分更为复杂。例如在膜曝气生物膜反应器中,曝气膜和生物膜需要分开界定,因此存在两个区域间物质的流动和传递,需要额外建立方程对传质通量或速率进行表征[20,43]。在生物膜区域内,又进一步划分为完全混合液体部分、固体生物膜部分和生物膜内孔隙水部分,因此生物膜的孔隙率、密度等指标也会对模型预测结果产生影响,需要逐一建立假设值[65]。生物膜区域内也存在液相和生物膜之间的物质和生物量传递,两相间的边界层厚度也需要设定[66]。假设生物膜体系中存在生物量的扩散,由此会导致PPCPs的生物降解区域发生变化,部分PPCPs由液相中悬浮生物量降解,另一部分在生物膜内部被降解,PPCPs的浓度变化方程也需要分区域建立[67]。部分研究为了简化PPCPs在生物膜体系中的去除,则不考虑生物量的扩散[43]。

模型的预测结果受到多种运行参数的影响。与活性污泥体系相比,生物膜体系中存在更多影响模型预测结果的特异性参数。由于氧气、污水基质、微生物等会在生物膜内分层,因此生物膜厚度对PPCPs的去除效果和降解机制会产生重要的影响。建立生物膜PPCPs去除模型时,对生物膜厚度的定量表达是影响预测结果的关键步骤。生物膜上会发生生物量的生长和衰减、附着和脱附等现象,首先需要设定生物膜厚度初始值,再通过对四个过程的定量描述来表达生物膜厚度的变化[15]。生物量附着在多数生物膜体系中可忽略,因此生物膜模型采用生物量生长和脱附的函数表征生物膜厚度[68-70]。Liu等[71]提出,生物膜厚度作为生物膜模型的敏感参数,通过公式假设可能会影响模型准确性,电子显微镜直接测量会更加精确。除生物膜厚度外,生物膜表面积与微生物生长相关,也可能对PPCPs生物降解产生影响,但由于载体形状复杂等因素,生物膜表面积的定量方法尚不明确[72]。

综上所述,在生物膜体系中PPCPs去除所涉及的物质流动和影响参数更为复杂,生物膜模型预测难度更高,这也可能是生物膜模型的发展落后于活性污泥模型的原因[73]。

-

微生物降解是污水中PPCPs去除的主要机制。PPCPs可由HB和AOB直接代谢或共代谢去除[74]。其中AOB存在非特异性氨单加氧酶(ammonium monooxygenase,AMO),可以降解芳香族化合物和脂肪族化合物等有机物[59],在PPCPs生物降解中发挥了重要作用。与AOB和HB相比,聚磷菌降解PPCPs的能力很低[53],在模型建立时可忽略。不同PPCPs在不同微生物群落中的生物降解效果和途径存在差异。评价不同微生物对PPCPs的降解性能,有利于富集功能菌,优化PPCPs去除效果。通过将不同微生物的不同降解途径纳入模型,可用于评价不同微生物对PPCPs的降解性能。

Sathyamoorthy等[56]建立了包含不同微生物及不同PPCPs降解途径的Monod动力学模型,并将该模型引入活性污泥模型框架中,研究了3种β受体阻滞剂——阿替洛尔、美托洛尔和索他洛尔在硝化过程中的生物降解。研究发现美托洛尔和索他洛尔在硝化环境中无法被去除,而阿替洛尔则可被硝化菌去除80%左右。Peng等[49]在活性污泥模型框架内引入雌激素的生物降解和吸附过程,模拟雌激素在硝化过程中的去除。研究发现不同微生物对不同雌激素的降解性能不同。雌激素E2主要由AOB直接代谢,而雌激素E3主要由HB直接代谢。这些结果表明,微生物对PPCPs的降解性能和途径与PPCPs结构、官能团或功能没有明显关系[75]。微生物对PPCPs降解性能的研究结论不可相互借鉴,需单独进行研究。

通过改变水质或运行参数可以提高微生物对PPCPs的降解性能。例如升高进水COD浓度,可以提高HB对PPCPs的降解性能。Peng等[49]改变雌激素去除模型的COD输入值,预测不同雌激素在不同COD浓度下的微生物降解性能。随着COD浓度升高,雌激素E3的主导功能菌由AOB转化为HB,去除率也随之升高。因此当雌激素E3为主要污染物时,额外添加碳源可以有效优化去除。Peng等[43]建立了膜曝气生物膜模型,并在该模型中引入AOB和HB对药物的降解过程,模型预测发现升高COD浓度可以将药物的主要功能菌转化为HB,并提高总体去除率。然而,有研究利用数学模型预测发现升高COD浓度会降低氮去除率,提高碳足迹[49,76]。因此如何在满足水质标准的基础上强化PPCPs去除,是PPCPs去除模型不可忽视的问题。

改变SRT、DO等条件可以提高AOB对PPCPs的降解性能。Yu等[60]利用活性污泥模型预测出最有利于AOB生长的SRT和DO范围。削弱NOB与AOB对氧气的竞争,也可以提高AOB对PPCPs的降解性能[77]。Perez等[78]利用生物膜模型研究了NOB的有效抑制方法,如降低温度、提高氨氮浓度等措施均可以抑制NOB,提高AOB丰度。Wang等[79]利用生物膜模型研究了游离氨和DO对硝化菌的影响,设计出一套富集AOB的DO调控方案。总体来说,富集AOB是多参数综合影响的结果。利用模型调节参数富集功能菌是强化PPCPs去除的重要方式。

-

活性污泥和生物膜工艺是去除污水中PPCPs最经济有效的选择[80]。然而大多数污水中PPCPs的去除效果不理想,生物转化不彻底[81-83]。原因在于污水中PPCPs生物降解机制和限制因素尚不明确[8]。建立PPCPs去除模型可以解释PPCPs生物降解机制,筛选限制因素,并调节参数削弱限速步骤,提供PPCPs强化去除的调控策略。

共代谢基质和生长基质的竞争性抑制是影响共代谢去除PPCPs的关键限制因素。Sathyamoorthy等[56]研究发现AOB是阿替洛尔的降解功能菌,但阿替洛尔却对AOB生长存在抑制作用。Xu等[48]也提出在共代谢过程中,药物与AOB的生长基质氨氮之间存在竞争效应。当氨氮浓度高于20 mg·L−1 N时,药物的生物转化效率不会再提高。这可能因为药物浓度比铵离子浓度低几个数量级,从而导致对AMO活性位点的竞争[84]。Plósz等[18]建立ASM-X时发现当SS大于20 mg·L−1 COD时,磺胺甲恶唑、四环素和环丙沙星的转化速率可被抑制50%以上。共代谢基质和生长基质的竞争性抑制可通过开关函数的形式添加到PPCPs去除模型的动力学表达式中,控制PPCPs与生长基质之间的浓度比例,是优化PPCPs去除中必不可少的措施之一。

PPCPs的生物转化过程大多是可逆的[85],某些转化产物会在一定条件下逆转化为母体化合物,从而限制PPCPs的生物转化效率[86-87]。ASM-X将PPCPs转化产物作为组分CCJ引入模型,引入转化产物后ASM-X预测准确性提高[18,35]。但ASM-X模型没有分析影响逆转化过程的因素以及如何削弱逆转化过程。Nguyen等[45]将磺胺甲恶唑和其两种生物转化产物引入ASM-X,模拟了磺胺甲恶唑在实际污水中的生物转化。当微生物活性被抑制时,产物仍可通过胞外酶进行逆转化。在有氧和缺氧环境中,产物可彻底降解,母体化合物的浓度反而变高,证明逆转化过程限制了磺胺甲恶唑的生物转化。Polesel等[36]也利用ASM-X模拟了磺胺甲恶唑在污水中的去除,提出磺胺甲恶唑产物逆转化程度与污水处理工艺占地面积有关。建立PPCPs去除模型定量描述产物逆转化过程,有利于准确预测PPCPs转化产物浓度变化及逆转化程度,调节参数使逆转化过程的影响最小化,进一步优化PPCPs去除。

对于可吸附PPCPs来说,被吸附到固体内的PPCPs无法接触到微生物或胞外酶,也可能是限制PPCPs生物降解的原因之一[8]。通过PPCPs去除模型调控参数解吸这部分PPCPs使之释放到微生物环境中被降解去除,是今后模型应用值得发展的方向之一。

-

PPCPs去除受到工艺条件、水质参数、运行参数等多种因素影响[41],不同参数对不同PPCPs的影响作用不同,由生物降解去除的PPCPs受生物量影响较大,而由吸附去除的PPCPs受pH影响较大[88]。如何筛选并调控关键参数强化PPCPs去除是目前PPCPs去除研究中的难点。单纯的实验设计难以对每个参数进行研究,且无法比较连续参数值和多种参数共同对PPCPs去除的影响,因此无法获得PPCPs去除率效果最好的参数组合。数学模型可以预测在一定范围内多组参数的连续变化对PPCPs去除的影响,因此建立一种基于活性污泥和生物膜模型的PPCPs去除模型可较为准确地预测不同参数条件下PPCPs浓度变化,筛选出关键影响参数并得到最有利于去除的参数组合,为调控PPCPs去除和优化污水处理工艺运行条件提供参考。利用数学模型优化参数组合已应用于脱氮[89]、提高产能效率[90]、评价菌种生长情况[91]等,但在PPCPs去除方面的应用相对较少。

Peng等[46]利用ASM-X模拟磺胺甲恶唑及其转化产物在富集AOB条件下的共代谢生物转化。模型预测了在不同进水磺胺甲恶唑浓度、氨氮浓度、COD浓度、HRT和SRT的5种参数条件下,出水磺胺甲恶唑及其转化产物的浓度变化。模型预测结果表明,对磺胺甲恶唑去除率影响最大的运行参数是进水氨氮浓度。Peng等[43]建立生物膜药物去除模型研究了膜曝气生物膜反应器中氮和药物的共同转化。分别评估了氧气表面负荷、HRT和生物膜厚度三种参数对氮和药物去除率的影响,预测出氧气表面负荷和HRT对氮和药物去除率的共同作用,得到了在不影响氮去除的基础上,药物去除率最高的参数组合范围。除常规水质和运行参数外,传质通量、生物膜有效表面积、絮体污泥含量等实验难以测量的参数也对PPCPs去除起到了重要影响作用[72,92]。如何利用数学模型对这些参数进行定量模拟并预测它们对PPCPs去除的影响,得到最佳参数组合范围,是未来PPCPs去除模型应用的重要方向。

建立以活性污泥和生物膜模型为基础的PPCPs去除模型是预测并强化污水中PPCPs去除的重要工具。组分和过程的确定、动力学表达式的选择、关键系数的筛选和校准等步骤是PPCPs去除模型建立的关键。PPCPs去除模型可以解决污水中PPCPs及其产物难以定量的问题,评价微生物对PPCPs的降解性能,解释PPCPs的生物降解机制和限制因素,为强化污水中PPCPs去除指明方向。发挥PPCPs去除模型在优化参数组合上的优势,制定污水中PPCPs去除的调控策略,是今后模型应用的趋势。

-

(1) 建立以活性污泥和生物膜模型为基础的PPCPs去除模型是预测并强化污水中PPCPs去除的重要工具。PPCPs去除模型的建立难点在于完善初始进水组分和生物量的测定方法,选择更符合PPCPs去除过程的动力学表达,以及建立PPCPs去除中关键系数的校准方法。

(2) 生物膜体系中存在物质扩散、生物量分离等现象,所涉及的生化过程和物质流动更加复杂。生物膜厚度、生物膜表面积、传质通量等特异性参数会影响PPCPs去除。因此与活性污泥模型相比,PPCPs生物膜模型的建立更加复杂,应用难度更高。完善PPCPs生物膜模型的建立方法体系将在很大程度上推动PPCPs在生物膜体系中的强化去除。

(3) 目前PPCPs去除模型应用主要关注两个方面,一是评价不同微生物对PPCPs的降解性能;二是探究PPCPs的生物降解机制和限制因素,包括基质抑制效应、产物逆转化效应等。利用PPCPs去除模型调节参数富集功能菌并削弱限速步骤,是强化污水中PPCPs去除的重要方式。

(4) 如何利用PPCPs去除模型优化参数组合从而强化污水中PPCPs去除是未来模型研究的重要方向。关键在于如何利用模型对不同参数进行定量模拟,筛选并优化对PPCPs去除影响最大的参数组合,为调控污水中PPCPs的强化去除提供支撑。

活性污泥和生物膜模型预测污水中PPCPs去除研究进展

Prediction of PPCPs removal in wastewater by activated sludge and biofilm models

-

摘要: 药品及个人护理用品(pharmaceutical and personal care products,PPCPs)在污水中广泛检出,低浓度的PPCPs即可对生态环境和人体健康产生不利影响,污水处理厂出水排放是水环境PPCPs的重要源。活性污泥和生物膜工艺是目前最常用的污水生物处理工艺,这两种工艺涉及的生化过程复杂,影响因素众多,难以有效去除PPCPs。数学模型是污水处理工艺运行优化的重要工具。本文系统阐述了PPCPs去除模型的建立方法,包括物质和微生物组分及PPCPs去除过程的确定、动力学方程及关键系数的测定与校准、活性污泥和生物膜模型的异同等;综述了污水中PPCPs去除模型的应用研究进展,包括用于评价不同微生物对PPCPs的降解性能、探究污水中PPCPs的生物降解机制及限制因素、优化影响PPCPs去除的参数等,为精准调控污水中PPCPs去除提供参考。

-

关键词:

- 污水 /

- 药品及个人护理用品(PPCPs) /

- 去除模型 /

- 活性污泥 /

- 生物膜

Abstract: Pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) are often detected in wastewater. Low concentrations of PPCPs can cause toxicity to the ecological environment and human health. The effluent discharge from wastewater treatment plants is an important source of PPCPs into water environment. Activated sludge and biofilm processes are currently the most commonly used wastewater treatment processes. These two processes involve complex biochemical processes and have many operation parameters, making it difficult to remove PPCPs. Mathematical model is an important tool for the operation optimization in wastewater treatment plants. This study elaborates the establishment methods of PPCPs removal model, including the determination of components and processes, the calibration of kinetic coefficients, the differences between activated sludge models and biofilm models. In addition, the application of PPCPs removal model in evaluating different microbial degradation performance, including PPCPs biotransformation mechanisms, and optimization of operation parameters are reviewed. This study provides a reference for regulation of PPCPs removal in wastewater treatment plants.-

Key words:

- sewage /

- pharmaceutical and personal care products(PPCPs) /

- removal model /

- activated sludge /

- biofilm

-

药品及个人护理用品(pharmaceutical and personal care products,PPCPs)是水环境普遍存在的新型污染物,其中药品包括抗生素、激素、止痛药、消炎药、β-阻滞剂等。个人护理产品包括防腐剂、杀菌剂/消毒剂、驱虫剂、防晒剂、香水等[1-2]。污水处理厂出水排放是PPCPs进入水环境的主要途径之一[3-4]。尽管污水中PPCPs浓度不高(ng L−1—μg L−1),但PPCPs长期暴露会对生态环境[5]和人体健康[6-7]产生不利影响,因此提高污水中PPCPs的去除效果是急需解决的问题。

活性污泥和生物膜法是最常用的两种污水处理工艺,主要为去除碳氮磷等常规水污染物设计,无法完全去除PPCPs等新型污染物。污水处理过程PPCPs的迁移转化机制复杂[8],且去除效果与污水处理工艺条件、运行参数、水质参数等多种因素密切相关[9-10],采用实验优化难以获取最佳去除效果的参数组合[11]。数学模型是预测并精准调控复杂条件下污染物去除规律的重要手段。国际水协会(Intemational Water Association,IWA)于1986年起相继推出活性污泥1、2、2D、3号模型和生物膜一维、二维、三维模型[12-17],这两种工艺模型利用矩阵表达系统中涉及的关键组分和过程,通过定量描述与物质降解、微生物生长等过程相关的动力学和化学计量系数,解释系统内部的各个主要活动,并能外推出其他实验条件下的过程,进行更有效的实验设计。活性污泥和生物膜模型已广泛应用于预测碳氮磷等传统物质的去除。随着污水中PPCPs等新型污染物的不断增加及其潜在的不利影响,如何修改和扩展已有的活性污泥和生物膜模型以强化PPCPs在污水中的去除引起了国内外研究者们的广泛关注。Plósz等[18]提出可用于评价外源痕量物质去除的活性污泥模型(ASM-X),该模型仅包括液相中母体化合物和可逆转化化合物以及固相中的吸附化合物三个组分,不考虑其余可溶性化合物和生物量组分。ASM-X能够预测PPCPs及其转化产物在污水中的浓度变化,但该模型无法解释PPCPs降解机制,也无法优化PPCPs去除条件。

如何在原有模型基础上研发适用于预测并强化污水中PPCPs去除的数学模型是今后研究的重要方向。PPCPs去除模型的建立可以解决污水中PPCPs难以定量的问题,准确预测出水中PPCPs及其转化产物在不同条件下的浓度变化,并深入探究PPCPs在生物处理系统中的微生物降解性能、降解机制和主要限速因素,模拟不同运行参数对去除效果的影响,从而获得最有利于PPCPs去除的污水处理工艺参数组合。本文综述了PPCPs去除模型在评价不同微生物降解性能,探究PPCPs生物降解机制及限制因素,以及优化PPCPs去除参数方面的应用,为精准调控污水中PPCPs去除提供参考。

1. 污水中PPCPs去除模型建立(Modeling the removal of PPCPs from wastewater)

活性污泥和生物膜模型多用于预测碳氮磷等常规水污染物的去除。PPCPs的加入会使原有体系中的微生物活动发生变化,原始模型结构和动力学表达无法准确预测PPCPs的去除,因此必须根据PPCPs的去除规律对模型进行修正,并重新定义和校准影响PPCPs去除的动力学和化学计量系数。图1给出了PPCPs去除模型的建立步骤。

1.1 物质和微生物组分及PPCPs去除过程的确定

模型中的关键组分可大致分为四类:微生物、底物、衰减产物和溶解氧。在PPCPs去除模型中,对PPCPs具有生物降解作用的微生物(氨氧化细菌、异养细菌等)是模型中最关键的微生物组分。此外亚硝酸盐氧化细菌(nitrite oxidizing bacteria,NOB)是硝化反应的重要参与者,也是PPCPs去除模型必不可少的微生物组分。与这些微生物生长代谢相关的底物是模型中关键的物质组分。除碳、氮等生长底物外,PPCPs及其转化产物通常由微生物直接代谢或共代谢去除,因此PPCPs及其转化产物必须纳入模型组分。可溶性微生物产物和胞外聚合物作为微生物的生长底物和衰减产物,影响微生物交互和物质利用等过程,也是模型中常见的物质组分[19-21]。溶解氧是活性污泥和生物膜工艺得以运行的关键条件,也是PPCPs去除模型的关键组分[19]。

进水COD和生物量组分的定量是目前模型应用的主要挑战之一。呼吸速率法与微生物生长代谢直接相关,能够提供更多关于微生物生长和物质降解的信息,广泛应用于模型研究[22-23],是活性污泥和生物膜体系中最常用的进水COD组分表征方法,即根据耗氧速率(OUR)的变化计算不同COD组分浓度[24-26]。硝化细菌和异养细菌是PPCPs生物降解的主要微生物,对这两种微生物定量是提高模型预测准确性的关键。传统的生物量测定方法包括平板计数法和MPN计数法[27],或用混合液悬浮固体(MLSS)来代替生物量[28]。此类方法误差大,不利于模型的准确预测。近年来,荧光原位杂交技术(FISH)、流式细胞术(FCM)、聚合酶链反应(PCR)、高通量测序(HTS)等分子技术[29-32]在微生物定量中发挥了重要作用。然而,由于操作过程复杂且耗时长,以及所需的特殊设备和高昂的维护成本,分子技术很少用于实际污水处理的管理和操作。用于微生物定量的呼吸速率法包括指数生长法、内源呼吸速率法和最大比呼吸速率法[33]。其中内源呼吸法凭借过程稳定、测定指标少等优点,在模型建立中应用更广泛。

模型最基础的过程是微生物利用不同生长底物的生长和衰减过程。PPCPs去除过程的确定则与PPCPs性质密切相关,对于双氯芬酸、卡马西平等强吸附PPCPs来说,吸附和脱附过程是模型中的关键过程[34]。而对于吸附可忽略的PPCPs来说,不同微生物对PPCPs的不同代谢途径是模型的关键过程,主要包括氨氧化细菌(ammonia oxidizing bacteria,AOB)和异养细菌(heterotrophic bacteria,HB)对PPCPs的共代谢和直接代谢两种途径。产物PPCPs逆转化为母体PPCPs也是PPCPs去除模型的关键过程,用于研究逆转化过程对模型预测结果的影响[35-36]。

1.2 动力学方程及关键系数的测定与校准

组分和过程确定后,模型的基本架构得以建立,需选择合适的动力学表达式准确描述PPCPs的去除过程。最简便的动力学表达式是伪一阶方程,即认为PPCPs的生物降解和吸附仅与PPCPs和生物量浓度有关[37-39]。在PPCPs浓度极低且生物量浓度基本稳定的条件下,伪一阶动力学可以描述PPCPs的去除[40-42]。另外PPCPs生物降解是一种酶促反应,还可以用Michaelis-Menten动力学描述[43-44],有研究发现Michaelis-Menten动力学准确性不如伪一阶动力学,可能因为酶的活性不是影响PPCPs生物降解的主要因素[8]。

伪一阶动力学和Michaelis-Menten动力学无法解释PPCPs生物降解机制及其与污水基质的关系,因为这两种动力学不区分微生物对PPCPs不同的降解过程,不包含影响PPCPs生物降解的各项因素。Monod方程将影响微生物生长代谢的操作参数和基质浓度作为开关函数引入表达式,例如溶解氧(SO)、溶解性可生物降解基质(SS)[19]、碳氮比[27]等。Monod动力学在揭示PPCPs共代谢机制方面发挥了重要作用,在活性污泥和生物膜模型中应用更广泛。Su等[27]比较了Logistic动力学和Monod动力学在活性污泥模型中的预测精度。Logistic动力学以1/(1+eX)形式表达,其中X包括各过程中的影响因子。研究发现Logistic动力学的预测结果与实验值更接近,且对细微变化的反应更灵敏。这可能是因为Logistic动力学包含的参数更多,但同时增加了模型建立的复杂性。表1列举了不同类型PPCPs在不同处理工艺中适用的降解动力学表达式。

表 1 不同类型PPCPs在不同处理工艺中适用的降解动力学表达式Table 1. Degradation kinetics equations of different PPCPs in different treatmentsPPCPs 处理工艺Treatment process 降解动力学Degradation kinetics 参考文献References 磺胺甲恶唑 好氧活性污泥 Monod动力学 [45-46] 厌氧活性污泥 伪一阶动力学 [45] 阿昔洛韦 硝化活性污泥 伪一阶动力学 [47] Monod动力学 [48] 雌激素 硝化活性污泥 Monod动力学 [49] 天然水体 Logistic动力学 [50] 甲基异噻唑啉酮 微藻Scenedesmus sp. LX1 Logistic动力学 [51] 红霉素 硝化活性污泥 伪一阶动力学 [52] 罗红霉素 佳乐麝香 吐纳麝香 氟西汀 布洛芬 硝化活性污泥 Monod动力学 [52] 甲氧萘丙酸 甲氧苄氧嘧啶 好氧活性污泥 伪一阶动力学 [53] 非诺洛芬 好氧活性污泥 伪一阶动力学 [54] 卡马西平 纯菌Pseudomonas sp. CBZ-4 Monod动力学 [55] 阿替洛尔 硝化活性污泥 Monod动力学 [48,56] 对乙酸氨基酚 基于H2O2的UFBR Michaelis-Menten动力学 [44] 各类药物 MABR Michaelis-Menten动力学 [43] 各类PPCPs 好氧活性污泥和部分硝化厌氧氨氧化 伪一阶动力学 [57] 动力学表达式包含了许多系数,有两类系数无须估测,可直接采用默认值,一是不会随污水水质的不同而有显著变化的系数,如自养菌产率系数YA、自养菌衰减系数bA等;二是起到开关函数的作用,取值对结果影响不大的系数,如异养菌和自养菌的氧半饱和系数KO, H、KO, A等。但另外一些系数依赖于污水水质、微生物结构等诸多因素,且对模型预测结果有很大影响,需要实际测定与校准。敏感性分析的目的是研究模型系数误差大小对模型预测结果的影响,从而筛选关键系数[58]。每种PPCPs都具有一组特定的高敏感度系数集,对这组高敏感度系数集的校准是提高模型预测准确性的关键。在大多数与PPCPs去除模型相关的研究中,与降解菌生长速率(uAOB、uHB)和PPCPs生物转化(TAOB、kAOB等)相关的系数对预测结果的影响最大[49,59]。这些关键系数可以通过呼吸速率法直接测定[60-61],但更多情况下通过拟合水质指标的实测值和模拟值进行校准,即最小化实测值和模拟值的均方根误差(RMSE)、和方差(SSE)或相对误差(RE)等指标[21,56]。另外,这些系数受到多种运行参数(如pH和温度)的影响,因此在PPCPs去除过程中保持pH在中性范围且基本恒定是很有必要的,同时可用修正后的Arrhenius公式来描述温度与系数的关系,提出不同的温度校正因子[62-64]。系数的敏感性分析和校准可通过Aquasim、MATLAB等软件进行分析。

1.3 活性污泥和生物膜模型的异同

生物膜模型与活性污泥模型采用一致的矩阵表达形式,建模流程大体相似,且生物膜体系和活性污泥体系中PPCPs的去除机制都为吸附和生物降解去除,因此生物膜模型和活性污泥模型可采用一致的动力学表达公式。图2列举了这两种模型中PPCPs由不同途径去除的动力学方程。但由于生物膜体系所涉及的物质流动更加复杂,因此建立PPCPs生物膜去除模型需要对更多过程和参数进行定量描述。

生物膜体系中存在的传质现象和生物量的分离,一直是生物膜模型建立的难点[65]。模型建立时需要对反应区域进行分块。如图2所示,在活性污泥模型中,PPCPs和其它物质可假定都在液相中被生物降解,而生物膜模型的区域划分更为复杂。例如在膜曝气生物膜反应器中,曝气膜和生物膜需要分开界定,因此存在两个区域间物质的流动和传递,需要额外建立方程对传质通量或速率进行表征[20,43]。在生物膜区域内,又进一步划分为完全混合液体部分、固体生物膜部分和生物膜内孔隙水部分,因此生物膜的孔隙率、密度等指标也会对模型预测结果产生影响,需要逐一建立假设值[65]。生物膜区域内也存在液相和生物膜之间的物质和生物量传递,两相间的边界层厚度也需要设定[66]。假设生物膜体系中存在生物量的扩散,由此会导致PPCPs的生物降解区域发生变化,部分PPCPs由液相中悬浮生物量降解,另一部分在生物膜内部被降解,PPCPs的浓度变化方程也需要分区域建立[67]。部分研究为了简化PPCPs在生物膜体系中的去除,则不考虑生物量的扩散[43]。

模型的预测结果受到多种运行参数的影响。与活性污泥体系相比,生物膜体系中存在更多影响模型预测结果的特异性参数。由于氧气、污水基质、微生物等会在生物膜内分层,因此生物膜厚度对PPCPs的去除效果和降解机制会产生重要的影响。建立生物膜PPCPs去除模型时,对生物膜厚度的定量表达是影响预测结果的关键步骤。生物膜上会发生生物量的生长和衰减、附着和脱附等现象,首先需要设定生物膜厚度初始值,再通过对四个过程的定量描述来表达生物膜厚度的变化[15]。生物量附着在多数生物膜体系中可忽略,因此生物膜模型采用生物量生长和脱附的函数表征生物膜厚度[68-70]。Liu等[71]提出,生物膜厚度作为生物膜模型的敏感参数,通过公式假设可能会影响模型准确性,电子显微镜直接测量会更加精确。除生物膜厚度外,生物膜表面积与微生物生长相关,也可能对PPCPs生物降解产生影响,但由于载体形状复杂等因素,生物膜表面积的定量方法尚不明确[72]。

综上所述,在生物膜体系中PPCPs去除所涉及的物质流动和影响参数更为复杂,生物膜模型预测难度更高,这也可能是生物膜模型的发展落后于活性污泥模型的原因[73]。

2. 污水中PPCPs去除模型的应用研究(Application study of PPCPs removal model from wastewater)

2.1 评价不同微生物对PPCPs的降解性能

微生物降解是污水中PPCPs去除的主要机制。PPCPs可由HB和AOB直接代谢或共代谢去除[74]。其中AOB存在非特异性氨单加氧酶(ammonium monooxygenase,AMO),可以降解芳香族化合物和脂肪族化合物等有机物[59],在PPCPs生物降解中发挥了重要作用。与AOB和HB相比,聚磷菌降解PPCPs的能力很低[53],在模型建立时可忽略。不同PPCPs在不同微生物群落中的生物降解效果和途径存在差异。评价不同微生物对PPCPs的降解性能,有利于富集功能菌,优化PPCPs去除效果。通过将不同微生物的不同降解途径纳入模型,可用于评价不同微生物对PPCPs的降解性能。

Sathyamoorthy等[56]建立了包含不同微生物及不同PPCPs降解途径的Monod动力学模型,并将该模型引入活性污泥模型框架中,研究了3种β受体阻滞剂——阿替洛尔、美托洛尔和索他洛尔在硝化过程中的生物降解。研究发现美托洛尔和索他洛尔在硝化环境中无法被去除,而阿替洛尔则可被硝化菌去除80%左右。Peng等[49]在活性污泥模型框架内引入雌激素的生物降解和吸附过程,模拟雌激素在硝化过程中的去除。研究发现不同微生物对不同雌激素的降解性能不同。雌激素E2主要由AOB直接代谢,而雌激素E3主要由HB直接代谢。这些结果表明,微生物对PPCPs的降解性能和途径与PPCPs结构、官能团或功能没有明显关系[75]。微生物对PPCPs降解性能的研究结论不可相互借鉴,需单独进行研究。

通过改变水质或运行参数可以提高微生物对PPCPs的降解性能。例如升高进水COD浓度,可以提高HB对PPCPs的降解性能。Peng等[49]改变雌激素去除模型的COD输入值,预测不同雌激素在不同COD浓度下的微生物降解性能。随着COD浓度升高,雌激素E3的主导功能菌由AOB转化为HB,去除率也随之升高。因此当雌激素E3为主要污染物时,额外添加碳源可以有效优化去除。Peng等[43]建立了膜曝气生物膜模型,并在该模型中引入AOB和HB对药物的降解过程,模型预测发现升高COD浓度可以将药物的主要功能菌转化为HB,并提高总体去除率。然而,有研究利用数学模型预测发现升高COD浓度会降低氮去除率,提高碳足迹[49,76]。因此如何在满足水质标准的基础上强化PPCPs去除,是PPCPs去除模型不可忽视的问题。

改变SRT、DO等条件可以提高AOB对PPCPs的降解性能。Yu等[60]利用活性污泥模型预测出最有利于AOB生长的SRT和DO范围。削弱NOB与AOB对氧气的竞争,也可以提高AOB对PPCPs的降解性能[77]。Perez等[78]利用生物膜模型研究了NOB的有效抑制方法,如降低温度、提高氨氮浓度等措施均可以抑制NOB,提高AOB丰度。Wang等[79]利用生物膜模型研究了游离氨和DO对硝化菌的影响,设计出一套富集AOB的DO调控方案。总体来说,富集AOB是多参数综合影响的结果。利用模型调节参数富集功能菌是强化PPCPs去除的重要方式。

2.2 探究污水中PPCPs的生物降解机制及限制因素

活性污泥和生物膜工艺是去除污水中PPCPs最经济有效的选择[80]。然而大多数污水中PPCPs的去除效果不理想,生物转化不彻底[81-83]。原因在于污水中PPCPs生物降解机制和限制因素尚不明确[8]。建立PPCPs去除模型可以解释PPCPs生物降解机制,筛选限制因素,并调节参数削弱限速步骤,提供PPCPs强化去除的调控策略。

共代谢基质和生长基质的竞争性抑制是影响共代谢去除PPCPs的关键限制因素。Sathyamoorthy等[56]研究发现AOB是阿替洛尔的降解功能菌,但阿替洛尔却对AOB生长存在抑制作用。Xu等[48]也提出在共代谢过程中,药物与AOB的生长基质氨氮之间存在竞争效应。当氨氮浓度高于20 mg·L−1 N时,药物的生物转化效率不会再提高。这可能因为药物浓度比铵离子浓度低几个数量级,从而导致对AMO活性位点的竞争[84]。Plósz等[18]建立ASM-X时发现当SS大于20 mg·L−1 COD时,磺胺甲恶唑、四环素和环丙沙星的转化速率可被抑制50%以上。共代谢基质和生长基质的竞争性抑制可通过开关函数的形式添加到PPCPs去除模型的动力学表达式中,控制PPCPs与生长基质之间的浓度比例,是优化PPCPs去除中必不可少的措施之一。

PPCPs的生物转化过程大多是可逆的[85],某些转化产物会在一定条件下逆转化为母体化合物,从而限制PPCPs的生物转化效率[86-87]。ASM-X将PPCPs转化产物作为组分CCJ引入模型,引入转化产物后ASM-X预测准确性提高[18,35]。但ASM-X模型没有分析影响逆转化过程的因素以及如何削弱逆转化过程。Nguyen等[45]将磺胺甲恶唑和其两种生物转化产物引入ASM-X,模拟了磺胺甲恶唑在实际污水中的生物转化。当微生物活性被抑制时,产物仍可通过胞外酶进行逆转化。在有氧和缺氧环境中,产物可彻底降解,母体化合物的浓度反而变高,证明逆转化过程限制了磺胺甲恶唑的生物转化。Polesel等[36]也利用ASM-X模拟了磺胺甲恶唑在污水中的去除,提出磺胺甲恶唑产物逆转化程度与污水处理工艺占地面积有关。建立PPCPs去除模型定量描述产物逆转化过程,有利于准确预测PPCPs转化产物浓度变化及逆转化程度,调节参数使逆转化过程的影响最小化,进一步优化PPCPs去除。

对于可吸附PPCPs来说,被吸附到固体内的PPCPs无法接触到微生物或胞外酶,也可能是限制PPCPs生物降解的原因之一[8]。通过PPCPs去除模型调控参数解吸这部分PPCPs使之释放到微生物环境中被降解去除,是今后模型应用值得发展的方向之一。

2.3 优化影响PPCPs去除的参数

PPCPs去除受到工艺条件、水质参数、运行参数等多种因素影响[41],不同参数对不同PPCPs的影响作用不同,由生物降解去除的PPCPs受生物量影响较大,而由吸附去除的PPCPs受pH影响较大[88]。如何筛选并调控关键参数强化PPCPs去除是目前PPCPs去除研究中的难点。单纯的实验设计难以对每个参数进行研究,且无法比较连续参数值和多种参数共同对PPCPs去除的影响,因此无法获得PPCPs去除率效果最好的参数组合。数学模型可以预测在一定范围内多组参数的连续变化对PPCPs去除的影响,因此建立一种基于活性污泥和生物膜模型的PPCPs去除模型可较为准确地预测不同参数条件下PPCPs浓度变化,筛选出关键影响参数并得到最有利于去除的参数组合,为调控PPCPs去除和优化污水处理工艺运行条件提供参考。利用数学模型优化参数组合已应用于脱氮[89]、提高产能效率[90]、评价菌种生长情况[91]等,但在PPCPs去除方面的应用相对较少。

Peng等[46]利用ASM-X模拟磺胺甲恶唑及其转化产物在富集AOB条件下的共代谢生物转化。模型预测了在不同进水磺胺甲恶唑浓度、氨氮浓度、COD浓度、HRT和SRT的5种参数条件下,出水磺胺甲恶唑及其转化产物的浓度变化。模型预测结果表明,对磺胺甲恶唑去除率影响最大的运行参数是进水氨氮浓度。Peng等[43]建立生物膜药物去除模型研究了膜曝气生物膜反应器中氮和药物的共同转化。分别评估了氧气表面负荷、HRT和生物膜厚度三种参数对氮和药物去除率的影响,预测出氧气表面负荷和HRT对氮和药物去除率的共同作用,得到了在不影响氮去除的基础上,药物去除率最高的参数组合范围。除常规水质和运行参数外,传质通量、生物膜有效表面积、絮体污泥含量等实验难以测量的参数也对PPCPs去除起到了重要影响作用[72,92]。如何利用数学模型对这些参数进行定量模拟并预测它们对PPCPs去除的影响,得到最佳参数组合范围,是未来PPCPs去除模型应用的重要方向。

建立以活性污泥和生物膜模型为基础的PPCPs去除模型是预测并强化污水中PPCPs去除的重要工具。组分和过程的确定、动力学表达式的选择、关键系数的筛选和校准等步骤是PPCPs去除模型建立的关键。PPCPs去除模型可以解决污水中PPCPs及其产物难以定量的问题,评价微生物对PPCPs的降解性能,解释PPCPs的生物降解机制和限制因素,为强化污水中PPCPs去除指明方向。发挥PPCPs去除模型在优化参数组合上的优势,制定污水中PPCPs去除的调控策略,是今后模型应用的趋势。

3. 结论与展望(Conclusion and outlook)

(1) 建立以活性污泥和生物膜模型为基础的PPCPs去除模型是预测并强化污水中PPCPs去除的重要工具。PPCPs去除模型的建立难点在于完善初始进水组分和生物量的测定方法,选择更符合PPCPs去除过程的动力学表达,以及建立PPCPs去除中关键系数的校准方法。

(2) 生物膜体系中存在物质扩散、生物量分离等现象,所涉及的生化过程和物质流动更加复杂。生物膜厚度、生物膜表面积、传质通量等特异性参数会影响PPCPs去除。因此与活性污泥模型相比,PPCPs生物膜模型的建立更加复杂,应用难度更高。完善PPCPs生物膜模型的建立方法体系将在很大程度上推动PPCPs在生物膜体系中的强化去除。

(3) 目前PPCPs去除模型应用主要关注两个方面,一是评价不同微生物对PPCPs的降解性能;二是探究PPCPs的生物降解机制和限制因素,包括基质抑制效应、产物逆转化效应等。利用PPCPs去除模型调节参数富集功能菌并削弱限速步骤,是强化污水中PPCPs去除的重要方式。

(4) 如何利用PPCPs去除模型优化参数组合从而强化污水中PPCPs去除是未来模型研究的重要方向。关键在于如何利用模型对不同参数进行定量模拟,筛选并优化对PPCPs去除影响最大的参数组合,为调控污水中PPCPs的强化去除提供支撑。

-

表 1 不同类型PPCPs在不同处理工艺中适用的降解动力学表达式

Table 1. Degradation kinetics equations of different PPCPs in different treatments

PPCPs 处理工艺Treatment process 降解动力学Degradation kinetics 参考文献References 磺胺甲恶唑 好氧活性污泥 Monod动力学 [45-46] 厌氧活性污泥 伪一阶动力学 [45] 阿昔洛韦 硝化活性污泥 伪一阶动力学 [47] Monod动力学 [48] 雌激素 硝化活性污泥 Monod动力学 [49] 天然水体 Logistic动力学 [50] 甲基异噻唑啉酮 微藻Scenedesmus sp. LX1 Logistic动力学 [51] 红霉素 硝化活性污泥 伪一阶动力学 [52] 罗红霉素 佳乐麝香 吐纳麝香 氟西汀 布洛芬 硝化活性污泥 Monod动力学 [52] 甲氧萘丙酸 甲氧苄氧嘧啶 好氧活性污泥 伪一阶动力学 [53] 非诺洛芬 好氧活性污泥 伪一阶动力学 [54] 卡马西平 纯菌Pseudomonas sp. CBZ-4 Monod动力学 [55] 阿替洛尔 硝化活性污泥 Monod动力学 [48,56] 对乙酸氨基酚 基于H2O2的UFBR Michaelis-Menten动力学 [44] 各类药物 MABR Michaelis-Menten动力学 [43] 各类PPCPs 好氧活性污泥和部分硝化厌氧氨氧化 伪一阶动力学 [57] -

[1] KOSMA C I, LAMBROPOULOU D A, ALBANIS T A. Occurrence and removal of PPCPs in municipal and hospital wastewaters in Greece [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2010, 179(1/2/3): 804-817. [2] LIU J L , WONG M H. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs): A review on environmental contamination in China[J]. Environment International, 2013, 59: 208-224. [3] EGGEN R I L,HOLLENDER J,JOSS A,et al. Reducing the discharge of micropollutants in the aquatic environment:The benefits of upgrading wastewater treatment plants [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(14): 7683-7689. [4] LUO Y L, GUO W S, NGO H H, et al. A review on the occurrence of micropollutants in the aquatic environment and their fate and removal during wastewater treatment [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 473/474: 619-641. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.12.065 [5] HERNANDO M D, MEZCUA M, FERNANDEZ A A R, et al. Environmental risk assessment of pharmaceutical residues in wastewater effluents, surface waters and sediments [J]. Talanta, 2006, 69(2): 334-342. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.09.037 [6] RAJAPAKSHA A U, VITHANAGE M, LIM J E, et al. Invasive plant-derived biochar inhibits sulfamethazine uptake by lettuce in soil [J]. Chemosphere, 2014, 111: 500-504. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.04.040 [7] VITHANAGE M, RAJAPAKSHA A U, TANG X, et al. Sorption and transport of sulfamethazine in agricultural soils amended with invasive-plant-derived biochar [J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2014, 141: 95-103. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.02.030 [8] GONZALEZ G L, MAURICIO I M, CARBALLA M, et al. Why are organic micropollutants not fully biotransformed? A mechanistic modelling approach to anaerobic systems [J]. Water Research, 2018, 142: 115-128. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.05.032 [9] BULLOCH D N, NELSON E D, CARR S A, et al. Occurrence of halogenated transformation products of selected pharmaceuticals and personal care products in secondary and tertiary treated wastewaters from southern California [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(4): 2044-2051. [10] EVGENIDOU E N, KONSTANTINOU I K, LAMBROPOULOU D A. Occurrence and removal of transformation products of PPCPs and illicit drugs in wastewaters: A review [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2015, 505: 905-926. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.021 [11] TIWARI B, SELLAMUTHU B, OUARDA Y, et al. Review on fate and mechanism of removal of pharmaceutical pollutants from wastewater using biological approach [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 224: 1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.11.042 [12] WANNER O, GUJER W. A multispecies biofilm model [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 1986, 28(3): 314-328. doi: 10.1002/bit.260280304 [13] HENZE M, GRADY C P L, GUJER W, et al. Activated sludge model No. 1, iawprc scientific and technical report, No. 1[M]London: IAWPRC, 1997: 10Ш-707Х. [14] GUJER W, HENZE M, MINO T, et al. The activated sludge model No. 2: biological phosphorus removal [J]. Water Science and Technology, 1995, 31(2): 1-11. doi: 10.2166/wst.1995.0061 [15] WANNER O, REICHERT P. Mathematical modeling of mixed-culture biofilms [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 1996, 49(2): 172-184. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960120)49:2<172::AID-BIT6>3.0.CO;2-N [16] HENZE M, GUJER W, MINO T, et al. Activated sludge model no. 2d, ASM2d [J]. Water Science and Technology, 1999, 39(1): 165-182. doi: 10.2166/wst.1999.0036 [17] GUJER W, HENZE M, MINO T, et al. Activated Sludge Model No. 3 [J]. Water Science and Technology, 1999, 39(1): 183-193. doi: 10.2166/wst.1999.0039 [18] PLÓSZ B G, LEKNES H, THOMAS K V. Impacts of competitive inhibition, parent compound formation and partitioning behavior on the removal of antibiotics in municipal wastewater treatment [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(2): 734-742. [19] GAO F, NAN J, LI S, et al. Modeling and simulation of a biological process for treating different COD: N ratio wastewater using an extended ASM1 model [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2018, 332: 671-681. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.09.137 [20] WANG Z, CHEN X M, NI B J, et al. Model-based assessment of chromate reduction and nitrate effect in a methane-based membrane biofilm reactor [J]. Water Research X, 2019, 5: 100037. doi: 10.1016/j.wroa.2019.100037 [21] PENG L, NGO H H, SONG S, et al. Heterotrophic denitrifiers growing on soluble microbial products contribute to nitrous oxide production in anammox biofilm: Model evaluation [J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2019, 242(JULa15): 309-314. [22] FRIEDRICH M and TAKACS I. A new interpretation of endogenous respiration profiles for the evaluation of the endogenous decay rate of heterotrophic biomass in activated sludge [J]. Water Research, 2013, 47(15): 5639-5646. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.06.043 [23] VAN L M C M, LOPEZ V C M, MEIJER S C F, et al. Twenty-five years of ASM1: Past, present and future of wastewater treatment modelling [J]. Journal of Hydroinformatics, 2015, 17(5): 697-718. doi: 10.2166/hydro.2015.006 [24] MURAT H S, INSEL G, UBAY C E, et al. COD fractionation and biodegradation kinetics of segregated domestic wastewater: black and grey water fractions [J]. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, 2010, 85(9): 1241-1249. [25] DULEKGURGEN E, DOGRUEL S, KARAHAN O, et al. Size distribution of wastewater COD fractions as an index for biodegradability [J]. Water Research, 2006, 40(2): 273-282. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.10.032 [26] CRAMER M, SCHELHORN P, KOTZBAUER U, et al. Degradation kinetics and COD fractioning of agricultural wastewaters from biogas plants applying biofilm respirometry [J]. Environmental Technology, 2021,42(15): 1-2401. [27] SU P, HE J, ZUO X, et al. Modelling the simultaneous effects of organic carbon and ammonium on two-step nitrification within a downward flow biofilm reactor [J]. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 2019, 125: 251-259. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2019.03.027 [28] DIONISI D, BORNORONI L, MAINELLI S, et al. Theoretical and experimental analysis of the role of sludge age on the removal of adsorbed micropollutants in activated sludge processes [J]. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2008, 47(17): 6775-6782. [29] ABZAZOU T, ARAUJO R M, AUSET M, et al. Tracking and quantification of nitrifying bacteria in biofilm and mixed liquor of a partial nitrification MBBR pilot plant using fluorescence in situ hybridization [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 541: 1115-1123. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.007 [30] KINET R, DZAOMUHO P, BAERT J, et al. Flow cytometry community fingerprinting and amplicon sequencing for the assessment of landfill leachate cellulolytic bioaugmentation [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2016, 214: 450-459. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.04.131 [31] QIN Y, HAN B, CAO Y, et al. Impact of substrate concentration on anammox-UBF reactors start-up[J] Bioresource Technology, 2017, 239: 422-429. [32] STEUERNAGEL L, DE L G E L, AZIZAN A, et al. Availability of carbon sources on the ratio of nitrifying microbial biomass in an industrial activated sludge [J]. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 2018, 129: 133-140. [33] LI Z H, HANG Z Y, LU M, et al. Difference of respiration-based approaches for quantifying heterotrophic biomass in activated sludge of biological wastewater treatment plants [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 664: 45-52. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.007 [34] SNIP L J, FLORES A X, PLÓSZ B G, et al. Modelling the occurrence, transport and fate of pharmaceuticals in wastewater systems [J]. Environmental Modelling & Software, 2014, 62: 112-127. [35] PLÓSZ B G, LANGFORD K H, THOMAS K V. An activated sludge modeling framework for xenobiotic trace chemicals (ASM-X): Assessment of diclofenac and carbamazepine [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2012, 109(11): 2757-2769. doi: 10.1002/bit.24553 [36] POLESEL F, ANDERSEN H R, TRAPP S, et al. Removal of antibiotics in biological wastewater treatment systems—A critical assessment using the activated sludge modeling framework for xenobiotics (ASM-X) [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(19): 10316-10334. [37] MONTEITH H D, PARKER W J, BELL J P, et al. Modeling the fate of pesticides in municipal wastewater treatment [J]. Water Environment Research, 1995, 67(6): 964-970. doi: 10.2175/106143095X133194 [38] BOEIJE G, SCHOWANEK D and VANROLLEGHEM P. Adaptation of the SimpleTreat chemical fate model to single-sludge biological nutrient removal wastewater treatment plants [J]. Water Science and Technology, 1998, 38(1): 211-218. doi: 10.2166/wst.1998.0051 [39] BYRNS G. The fate of xenobiotic organic compounds in wastewater treatment plants [J]. Water Research, 2001, 35(10): 2523-2533. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00529-7 [40] YANG S F, LIN C F, WU C J, et al. Fate of sulfonamide antibiotics in contact with activated sludge-sorption and biodegradation [J]. Water Research, 2012, 46(4): 1301-1308. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.12.035 [41] FERNANDEZ-FONTAINA E, PINHO I, CARBALLA M, et al. Biodegradation kinetic constants and sorption coefficients of micropollutants in membrane bioreactors [J]. Biodegradation, 2013, 24(2): 165-177. doi: 10.1007/s10532-012-9568-3 [42] BAALBAKI Z, TORFS E, YARGEAU V, et al. Predicting the fate of micropollutants during wastewater treatment: Calibration and sensitivity analysis [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017: 601-602,874-885. [43] PENG L, CHEN X M, XU Y F, et al. Biodegradation of pharmaceuticals in membrane aerated biofilm reactor for autotrophic nitrogen removal: A model-based evaluation [J]. Journal of Membrane Science, 2015, 494: 39-47. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2015.07.043 [44] BARATPOUR P and MOUSSAVI G. The accelerated biodegradation and mineralization of acetaminophen in the H2O2-stimulated upflow fixed-bed bioreactor (UFBR) [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 210: 1115-1123. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.07.135 [45] NGUYEN P Y, CARVALHO G, POLESEL F, et al. Bioaugmentation of activated sludge with achromobacter denitrificans PR1 for enhancing the biotransformation of sulfamethoxazole and its human conjugates in real wastewater: Kinetic tests and modelling [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2018, 352: 79-89. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.07.011 [46] PENG L, KASSOTAKI E, LIU Y, et al. Modelling cometabolic biotransformation of sulfamethoxazole by an enriched ammonia oxidizing bacteria culture [J]. Chemical Engineering Science, 2017, 173: 465-473. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2017.08.015 [47] XU Y F, YUAN Z G, NI B J. Biotransformation of acyclovir by an enriched nitrifying culture [J]. Chemosphere, 2017, 170: 25-32. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.12.014 [48] XU Y F, CHEN X M, YUAN Z G, et al. Modeling of pharmaceutical biotransformation by enriched nitrifying culture under different metabolic conditions [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(5): 2835-2843. [49] PENG L, DAI X H, LIU Y W, et al. Model-based assessment of estrogen removal by nitrifying activated sludge [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 197: 430-437. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.01.035 [50] VANDERMARKEN T, CROES K, van LANGENHOVE K, et al. Endocrine activity in an urban river system and the biodegradation of estrogen-like endocrine disrupting chemicals through a bio-analytical approach using DRE- and ERE-CALUX bioassays [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 201: 540-549. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.036 [51] WANG X X, WANG W L, DAO G H, et al. Mechanism and kinetics of methylisothiazolinone removal by cultivation of Scenedesmus sp. LX1 [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 386: 121959. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121959 [52] FERNANDEZ-FONTAINA E, CARBALLA M, OMIL F, et al. Modelling cometabolic biotransformation of organic micropollutants in nitrifying reactors [J]. Water Research, 2014, 65: 371-383. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.07.048 [53] OGUNLAJA O O, PARKER W J. Modeling the biotransformation of trimethoprim in biological nutrient removal system [J]. Water Science and Technology, 2017, 2017(1): 144-155. [54] CHEN X J, VOLLERTSEN J, NIELSEN J L, et al. Degradation of PPCPs in activated sludge from different WWTPs in Denmark [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2015, 24(10): 2073-2080. doi: 10.1007/s10646-015-1548-z [55] LI A, CAI R, DI C, et al. Characterization and biodegradation kinetics of a new cold-adapted carbamazepine-degrading bacterium, Pseudomonas sp. CBZ-4 [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 2013, 25(11): 2281-2290. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(12)60293-9 [56] SATHYAMOORTHY S, CHANDRAN K, RAMSBURG C A. Biodegradation and cometabolic modeling of selected beta blockers during ammonia oxidation [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(22): 12835-12843. [57] TABOADA S A, BEHERA C R, SIN G. , et al. Assessment of the fate of organic micropollutants in novel wastewater treatment plant configurations through an empirical mechanistic model [J]. the Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 716: 137079.1-137079.14. [58] WANG H C, CHENG H Y, WANG S S, et al. Efficient treatment of azo dye containing wastewater in a hybrid acidogenic bioreactor stimulated by biocatalyzed electrolysis [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 2016, 39: 198-207. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2015.10.014 [59] XU Y F, YUAN Z G, NI B J. Biotransformation of pharmaceuticals by ammonia oxidizing bacteria in wastewater treatment processes [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 566/567: 796-805. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.118 [60] YU L, CHEN S, CHEN W, et al. Experimental investigation and mathematical modeling of the competition among the fast-growing 'r-strategists' and the slow- growing 'K-strategists' ammonium-oxidizing bacteria and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria in nitrification [J]. the Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 702: 135049.1-135049.9. [61] NI B J, YU H Q, SUN Y J. Modeling simultaneous autotrophic and heterotrophic growth in aerobic granules [J]. Water Research, 2008, 42(6/7): 1583-1594. [62] REIJKEN C, GIORGI S, HURKMANS C, et al. Incorporating the influent cellulose fraction in activated sludge modelling [J]. Water Research, 2018, 144: 104-111. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.07.013 [63] ZHANG M, LI N, CHEN W J, et al. Steady-state and dynamic analysis of the single-stage anammox granular sludge reactor show that bulk ammonium concentration is a critical control variable to mitigate feeding disturbances [J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 251: 126361. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126361 [64] MENG J, LI J, LI J, et al. The effects of influent and operational conditions on nitrogen removal in an upflow microaerobic sludge blanket system: A model-based evaluation [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2020, 295: 122225. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122225 [65] HORN H, LACKNER S. Modeling of biofilm systems: A review [J]. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology, 2014, 146: 53-76. [66] WANNER O and MORGENROTH E. Biofilm modeling with AQUASIM [J]. Water Science and Technology, 2004, 49(11-12): 137-144. doi: 10.2166/wst.2004.0824 [67] VASILIADOU I A, MOLINA R, MARTINEZ F, et al. Experimental and modeling study on removal of pharmaceutically active compounds in rotating biological contactors [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2014, 274: 473-482. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.04.034 [68] NI B J, YUAN Z. A model-based assessment of nitric oxide and nitrous oxide production in membrane-aerated autotrophic nitrogen removal biofilm systems [J]. Journal of Membrane Science, 2013, 428: 163-171. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.10.049 [69] NI B J, SMETS B F, YUAN Z, et al. Model-based evaluation of the role of Anammox on nitric oxide and nitrous oxide productions in membrane aerated biofilm reactor [J]. Journal of Membrane Science, 2013, 446: 332-340. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2013.06.047 [70] TANG Y N, ZHAO H P, MARCUS A K, et al. A steady-state biofilm model for simultaneous reduction of nitrate and perchlorate, part 1: Model development and numerical solution [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(3): 1598-1607. [71] LIU T, GUO J H, HU S H, et al. Model-based investigation of membrane biofilm reactors coupling anammox with nitrite/nitrate-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation [J]. Environment International, 2020, 137: 105501. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105501 [72] LIU Y W, LI C Y, LACKNER S, et al. The role of interactions of effective biofilm surface area and mass transfer in nitrogen removal efficiency of an integrated fixed-film activated sludge system [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2018, 350: 992-999. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.06.053 [73] BOLTZ J P, MORGENROTH E, BROCKMANN D, et al. Systematic evaluation of biofilm models for engineering practice: components and critical assumptions [J]. Water Science and Technology, 2011, 64(4): 930-944. doi: 10.2166/wst.2011.709 [74] TRAN N H, URASE T, NGO H H, et al. Insight into metabolic and cometabolic activities of autotrophic and heterotrophic microorganisms in the biodegradation of emerging trace organic contaminants [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2013, 146: 721-731. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.07.083 [75] CAMACHO-MUÑOZ D, MARTÍN J, SANTOS J L, et al. Effectiveness of conventional and low-cost wastewater treatments in the removal of pharmaceutically active compounds [J]. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 2012, 223(5): 2611-2621. [76] LACKNER S, TERADA A, SMETS B F. Heterotrophic activity compromises autotrophic nitrogen removal in membrane-aerated biofilms: Results of a modeling study [J]. Water Research, 2008, 42(4/5): 1102-1112. [77] WINKLER M K H, KLEEREBEZEM R, KUENEN J G, et al. Segregation of biomass in cyclic anaerobic/aerobic granular sludge allows the enrichment of anaerobic ammonium oxidizing bacteria at low temperatures [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(17): 7330-7337. [78] PÉREZ J, LOTTI T, KLEEREBEZEM R, et al. Outcompeting nitrite-oxidizing bacteria in single-stage nitrogen removal in sewage treatment plants: A model-based study [J]. Water Research, 2014, 66: 208-218. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.08.028 [79] WANG Z, ZHENG M, XUE Y, et al. Free ammonia shock treatment eliminates nitrite-oxidizing bacterial activity for mainstream biofilm nitritation process [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020: 124682. [80] GRANDCLÉMENT C, SEYSSIECQ I, PIRAM A, et al. From the conventional biological wastewater treatment to hybrid processes, the evaluation of organic micropollutant removal: A review [J]. Water Research, 2017, 111: 297-317. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.01.005 [81] BLAIR B, NIKOLAUS A, HEDMAN C, et al. Evaluating the degradation, sorption, and negative mass balances of pharmaceuticals and personal care products during wastewater treatment [J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 134: 395-401. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.04.078 [82] FALÅS P, WICK A, CASTRONOVO S, et al. Tracing the limits of organic micropollutant removal in biological wastewater treatment [J]. Water Research, 2016, 95: 240-249. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.009 [83] GULDE R, ANLIKER S, KOHLER H P E, et al. Ion trapping of amines in protozoa: A novel removal mechanism for micropollutants in activated sludge [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(1): 52-60. [84] DAWAS-MASSALHA A, GUR-REZNIK S, LERMAN S, et al. Co-metabolic oxidation of pharmaceutical compounds by a nitrifying bacterial enrichment [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2014, 167: 336-342. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.06.003 [85] MEYERS R A. Molecular biology and biotechnology: A comprehensive desk reference[M]. John Wiley & Sons, 1995. [86] SU T, DENG H, BENSKIN J P, et al. Biodegradation of sulfamethoxazole photo-transformation products in a water/sediment test [J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 148: 518-525. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.01.049 [87] QU S, KOLODZIEJ E P, LONG S A, et al. Product-to-parent reversion of trenbolone: Unrecognized risks for endocrine disruption [J]. Science, 2013, 342(6156): 347-351. doi: 10.1126/science.1243192 [88] GUSMAROLI L, MENDOZA E, PETROVIC M, et al. How do WWTPs operational parameters affect the removal rates of EU Watch list compounds? [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 714: 136773. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136773 [89] CHEN X M, GUO J H, XIE G J, et al. A new approach to simultaneous ammonium and dissolved methane removal from anaerobic digestion liquor: A model-based investigation of feasibility [J]. Water Research, 2015, 85: 295-303. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.08.046 [90] FLORES-ALSINA X, FELDMAN H, MONJE V T, et al. Evaluation of anaerobic digestion post-treatment options using an integrated model-based approach [J]. Water Research, 2019, 156: 264-276. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.02.035 [91] WISNIEWSKI K, DI B A, MUNZ G, et al. Kinetic characterization of hydrogen sulfide inhibition of suspended anammox biomass from a membrane bioreactor [J]. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 2019(143): 48-57. [92] ABTAHI S M, PETERMANN M, JUPPEAU FLAMBARD A, et al. Micropollutants removal in tertiary moving bed biofilm reactors (MBBRs): Contribution of the biofilm and suspended biomass [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 643: 1464-1480. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.303 -

下载:

下载: