-

纳米氧化锌(ZnO nanoparticles,ZnO NPs)具有催化活性、强氧化性和高稳定性,广泛应用于半导体、染料、塑料添加剂、化妆品等许多领域[1]。在ZnO NPs系列产品的生命周期中,其不可避免地会进入生态系统[2],由其引发的生物安全性问题,引起了学者们的广泛关注[3]。近年来,在土壤、污水和污泥中均发现了ZnO NPs的存在。GOTTSCHALK等[4]通过建模模拟得出,欧洲和美国水环境中的ZnO NPs质量浓度分别为0.432 mg·L−1和0.3 mg·L−1,已达到损害水体生物的阈值。部分进入环境中的ZnO NPs最终会进入到污水处理系统中[5]。因此,有必要了解ZnO NPs对污水生物处理运行效果的影响。

人工湿地(constructed wetlands,CWs)具有运行成本低、无二次污染、景观价值高等优点,已广泛应用于污水处理中[6-7]。然而,在其长期运行过程中,基质表面会堆积大量的难降解有机物和微生物分泌的胞外聚合物(extracellular polymeric substances,EPS),同时EPS会吸附无机颗粒和有机物并形成致密的堵塞层,造成CWs的堵塞[8]。有研究表明,ZnO NPs溶解产生的Zn2+以及NPs的内化会损伤细胞[9-10],且其粒径越小,生物毒性越强[11],会刺激微生物产生更多的EPS[12]。EPS亲水组分可通过吸附ZnO NPs,降低其对微生物的生物毒性[13-14]。然而,大量的EPS粘附于基质表面,可能会降低基质层孔隙率[15-16],从而降低CWs的使用寿命。目前,有关ZnO NPs的粒径效应对CWs性能及堵塞的影响尚缺乏系统的研究,并且ZnO NPs的粒径与微生物相对丰度的关系尚未明确。

针对上述问题,本研究考察了3种不同粒径(15 nm、50 nm和90 nm)的ZnO NPs对CWs性能、渗透系数及EPS产量和特性的影响,探讨了微生物群落结构和多样性对不同粒径ZnO NPs的响应,以期为CWs的稳定运行提供参考。

-

称取0.5 g ZnO NPs(表1)于1 L超纯水中,用磁力搅拌器混合搅拌30 min后,装入棕色试剂瓶中。在25 ℃下,超声1 h[17],制得ZnO NPs悬浊液。使用前,悬浊液需超声1 h(25 ℃,500 W,40 kHz),防止ZnO NPs团聚。

-

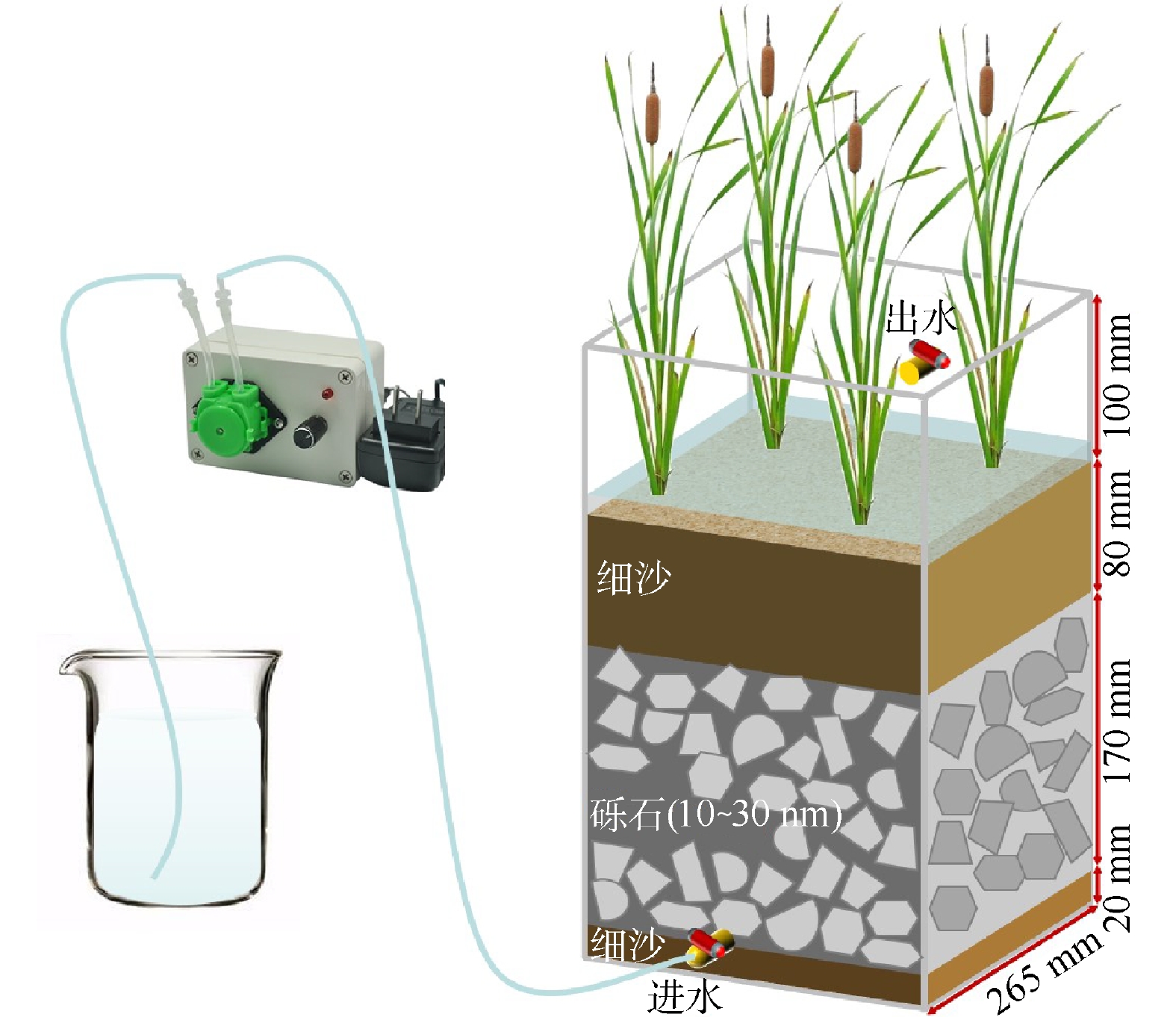

构建4组实验室规模的水平潜流人工湿地系统(horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland,HSFCWs),具体构造见图1。CWs反应器为PP材质(长、宽、高分别为26.5、26.5、37 cm)自下而上分别为2 cm细沙、17 cm砾石(粒径约10~30 mm)、细丝网(80 目)、8 cm 细沙和9株高约30 cm、生长状态均一的香蒲。为保证实验结果稳定可靠,在种入反应器前,先将香蒲放入内有1/4浓度的霍格兰氏植物培养液的塑料箱中,在25 ℃下培养驯化10 d左右。

-

分别以乙酸钠、氯化铵、磷酸二氢钾和磷酸氢二钾作为碳源、氮源和磷源配制人工污水,其COD、TN和TP分别约为216.00、11.10和3.84 mg·L−1。配水中添加1.00 mL·L−1微量元素,包括0.83 mg·L−1 KI、6.20 mg·L−1 硼酸、22.30 mg·L−1 MnSO4、8.60 mg·L−1 ZnSO4、0.025 mg·L−1 CuSO4、0.025 mg·L−1 CoCl2、5.56 g·L−1 FeSO4·7H2O和7.46 g·L−1 EDTA。使用1 mol·L−1盐酸或氢氧化钠调节进水pH在7.4左右。反应器进水为下进上出,水力停留时间(HRT)为2 d。

在填充到反应器前,利用青岛市李村河污水处理厂二沉池回流污泥作为接种污泥对砾石进行挂膜。将砾石没入污泥中,闷曝3 d,然后以人工污水作为进水,连续运行15 d左右。待砾石表面附着生物膜后,将其填入反应器内,每日投配定量人工污水。在运行过程中,测定COD、TP、

NH+4 -N和TN等指标。反应器达到稳定去除效果10 d后,开始在进水中投加ZnO NPs。ZnO NPs的环境本底值约为1.00 mg·L−1,考虑到ZnO NPs在环境中累积且不易降解的情况,本实验投加的ZnO NPs质量浓度为10.00 mg·L−1。反应器设置1组对照,即CW-对照(不投加ZnO NPs)和3组实验组,包括CW-15(15 nm ZnO NPs)、CW-50(50 nm ZnO NPs)和CW-90(90 nm ZnO NPs)。 -

实验期间,每隔1 d对4个反应器的进出水进行取样,利用重铬酸钾法测定COD,纳氏试剂分光光度法测定

NH+4 -N,碱性过硫酸钾消解法测定TN和钼锑抗分光光度法测定TP[18]。 -

CWs反应器连续进水,并处于饱和状态。采用常水头渗透系数法[19],测定CWs整体基质层的渗透系数,根据式(1)进行计算。

式中:K为渗透系数,cm·s−1;Q为单位时间水渗透量,mL·s−1;ΔH为水头损失,cm,ΔH=H1−H2;A为过水断面面积,cm2;L为渗透路径长度,cm;t为实验持续时间,s。

-

1) EPS提取和测定。待反应器停止运行后,从CWs顶部基质层收集20.0 g填料,用100 mL的NaCl(0.9%)溶液冲洗后,将得到的滤液倒入已灼烧至恒重的坩埚中在105 ℃下蒸干,然后再放入马弗炉在600 ℃下烧灼3 h,最后等坩埚冷却至恒重后测定堵塞物的质量。EPS采用改进的加热法进行提取[20],取40 mL的堵塞物混合液于4 000 r·min−1离心5 min,倒掉上清液后加入NaCl(0.05%,70 ℃)溶液至40 mL,混匀后于4 000 r·min−1离心10 min,所得上清液用0.45 µm的聚醚砜膜过滤后即为疏松附着型胞外聚合物(loosely bound EPS,LB-EPS);取LB-EPS离心后的沉淀物,加入NaCl(0.05%,60 ℃)溶液至40 mL,充分混合后在100 ℃下加热30 min,于4 000 r·min−1离心10 min,所得上清液用0.45 µm的聚醚砜膜过滤后即为紧密结合型胞外聚合物(tightly bound EPS,TB-EPS)。LB-EPS和TB-EPS中蛋白质(proteins,PN)和多糖(polysaccharides,PS)的含量分别通过Folin比色法[21]和蒽酮-硫酸比色法[22]测定。

2)三维荧光光谱分析。采用荧光分光光度计(日立F-4600)测定LB-EPS和TB-EPS的三维荧光激发发射矩阵光谱(3D-EEM)。以蒸馏水作为空白对照,测定参数设置如下:激发波长(Ex)为200~400 nm,扫描间隔5 nm;发射波长(Em)为200~500 nm,扫描间隔为5 nm;激发光和发射光的狭缝均为10 nm,扫描速度为2 400 nm·min−1[23]。

-

实验结束后,采集每个反应器不同高度的基质约100.00 g,混合后放入磷酸盐缓冲溶液中(10 mmol·L−1 Na2HPO4,8.50 g·L−1 NaCl),在超声波清洗机中(KQ-500B)处理5 min,然后涡漩1 min,将微生物从填料表面分离到溶液中。经离心处理后,微生物样品送往上海派森诺生物科技有限公司进行Illumina MiSeq/NovaSeq高通量测序。

-

实验数据统计分析采用SPSS 23.0软件进行方差齐性检验和单因素方差分析(采用邓肯多量程检验,P<0.05视为具有显著性差异);采用Canoco 5软件进行冗余分析(redundancy analysis,RDA)研究微生物群落和环境因子之间的关系;采用Matlab 2018a软件绘制3D-EEM光谱图,去除拉曼散射和瑞利散射,并进行归一化处理;采用OriginLab 2021和R语言(4.0.4)绘图及数据分析。

-

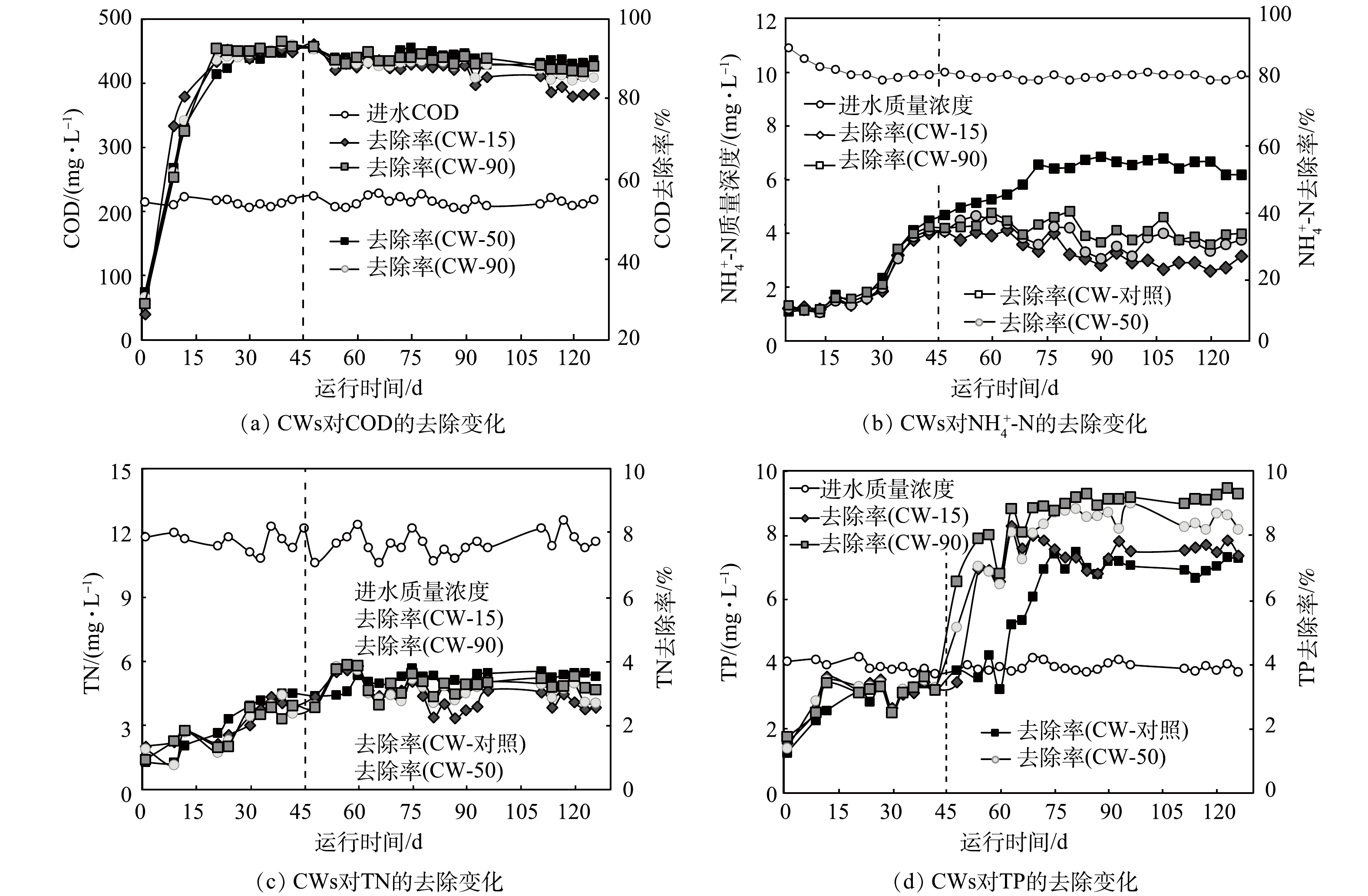

系统稳定运行45 d后,在进水中投加10.00 mg·L−1不同粒径的ZnO NPs悬浊液。如图2(a)所示,在投加10.00 mg·L−1不同粒径的ZnO NPs前,CW-对照、CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对COD的去除率分别为88.70%、91.40%、92.47%和95.01%;投加ZnO NPs 39 d后,与不加ZnO NPs的空白对照组相比,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对COD的平均去除率均有不同程度的下降,分别为8.73%、7.55%和6.97%。这表明较小粒径的ZnO NPs对COD的去除产生较明显的抑制作用。其原因可能归结于以下2点:ZnO NPs(10.00 mg·L−1)释放出的Zn2+离子具有生物毒性,导致异养微生物对COD的去除率下降[24];小粒径ZnO NPs与微生物细胞具有更大的接触面积[25],对异养微生物的生物代谢抑制更加明显,从而降低COD的去除率。

如图2(b)所示,在投加ZnO NPs 28 d后,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对

NH+4 -N的去除率呈降低趋势。与空白对照组相比,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对NH+4 -N的去除率分别下降了21.96%、17.75%和15.34%。CWs对NH+4 -N的去除主要在微生物吸收消耗有机营养物的硝化过程中,随着系统进入堵塞阶段,好氧环境受抑制(堵塞后DO在0.08~0.21 mg·L−1),硝化细菌的活性降低,不利于NH+4 -N的去除。如图2(c)所示,投加ZnO NPs后,CW-对照、CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对TN的去除率呈现先增加后降低的趋势。这可能是因为:反应前期ZnO NPs释放的低浓度的Zn2+会提高厌氧氨氧化菌(anaerobic-oxidizing bacteria,AOB)的代谢活性,从而消耗反应器中剩余的亚硝酸盐,降低了TN的浓度[26]。然而,在投加ZnO NPs 24 d后,与空白对照组相比,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对TN的去除率分别下降了10.95%、10.00%和3.78%。

如图2(d)所示,在投加ZnO NPs 18 d后,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对TP的去除率有不同程度的增加,分别为42.49%、52.34%和56.38%。可以推测,随着堵塞的发生,基质中积累的EPS作为堵塞物的关键成分,引入了大量的磷吸附位点。此外,ZnO NPs释放的Zn2+与磷酸盐反应生成磷酸锌等络合物,也会抑制磷酸盐的释放[12],从而提高了CWs的除磷性能。

-

1) CWs渗透系数的变化。进水中连续投加不同粒径的ZnO NPs,稳定运行83 d后,4个CWs发生了不同程度的堵塞。如表2所示,CW-对照组的渗透系数维持在1.20×10−3 cm·s−1,而CW-15、CW-50和CW-90基质层的渗透系数明显变小,分别比CW-对照降低了71.17%、67.83%和37.50%。随着ZnO NPs在CWs中的累积,导致系统水流阻力增大,出现短流、返混等现象,从而缩短HRT。同时,CWs处理性能的下降导致营养物质不断积累,再加上ZnO NPs刺激微生物产生的EPS不断增多,加剧了堵塞的程度。

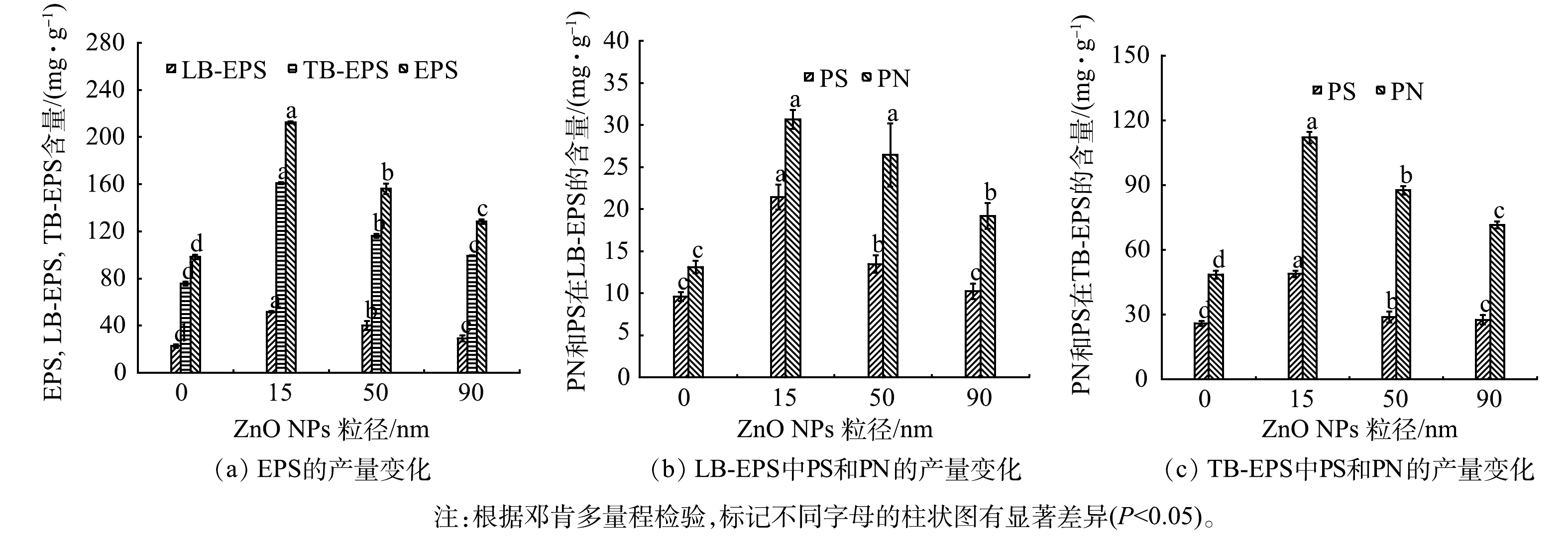

2) EPS和PN和PS产量的变化。有研究[27]表明,当微生物暴露于ZnO NPs等有毒物质下会产生应激反应并促进EPS的分泌。污泥絮体表面的EPS可以吸附ZnO NPs颗粒从而阻止其扩散到微生物中[28]。如图3(a)所示,与对照组(97.18 mg·g−1)相比,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90中的EPS分别增加到212.97、156.30和128.53 mg·g−1。15 nm的ZnO NPs可刺激微生物分泌EPS的量最多,这主要是因为小粒径的ZnO NPs比表面积大,更易于与微生物接触。有研究[29]表明,8 nm的ZnO NPs对金黄色葡萄球菌生长的抑制性强于50~70 nm ZnO NPs。此外,溶出的Zn2+会损伤细胞膜和DNA结构,可进一步诱导微生物持续分泌EPS[30]。

EPS主要由PN、PS以及少量核酸和脂质组成[12]。短期暴露于不同粒径的ZnO NPs后,LB-EPS(图3(b))和TB-EPS(图3(c))中PN和PS含量显著升高,尤以CW-15最为显著。这主要是因为小粒径的ZnO NPs毒性更强,易刺激微生物分泌更多的EPS。此外,ZnO NPs的短期暴露可能导致了大量生物量衰减和大量细胞破裂[31],从而使PN和PS含量大幅增加。

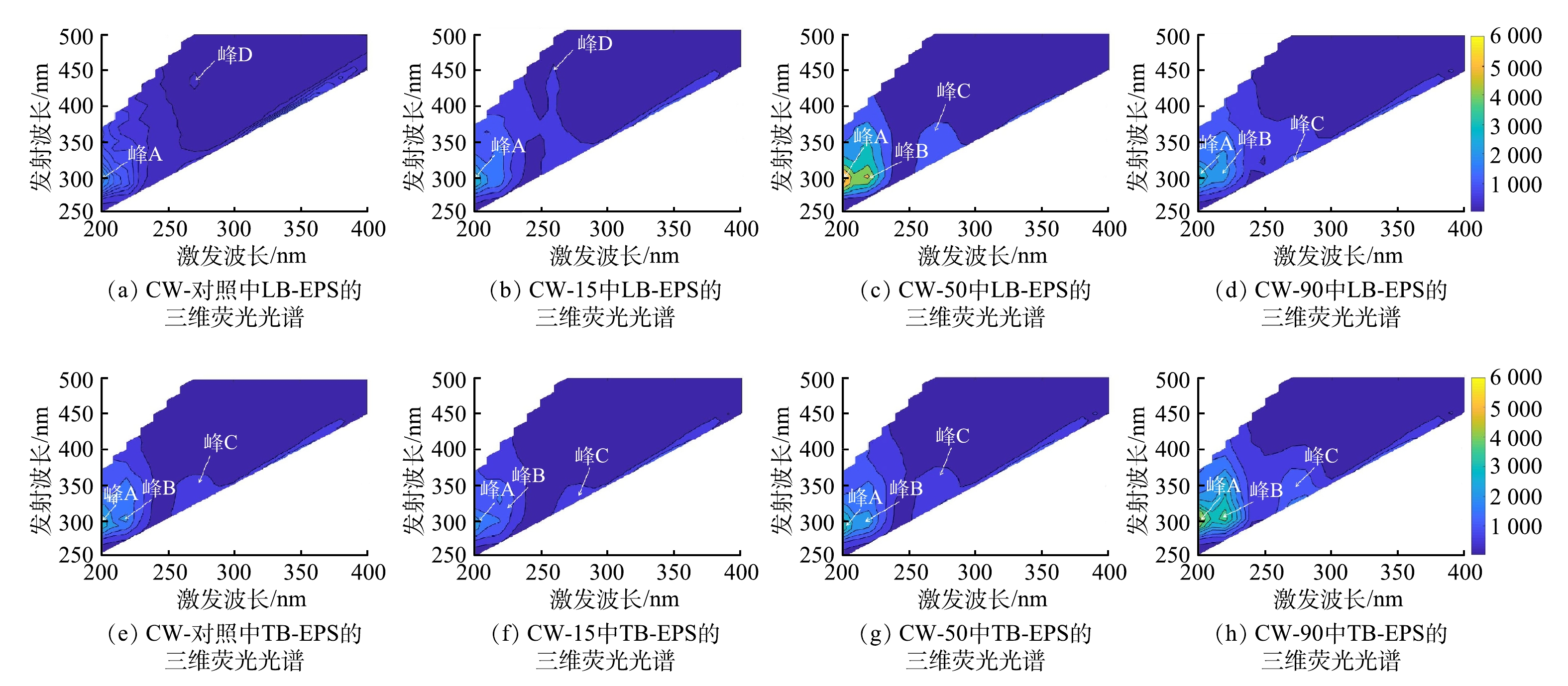

3) LB-EPS和TB-EPS主要组分分析。由图4可以看出,投加ZnO NPs前后LB-EPS和TB-EPS中识别出4个特征峰(峰A~D),其中峰A(200 nm/290~300 nm)为芳香族类蛋白物质,峰B(220~230 nm/300~330 nm)为类色氨酸物质,峰C(270~280 nm/300~330 nm)为类可溶性微生物副产物,而峰D(270 nm/420 nm)为类胡敏酸物质[32]。CW-对照和CW-15的LB-EPS主要为芳香族类蛋白和类胡敏酸物质,CW-50和CW-90的LB-EPS中峰D被峰C取代,这说明由于微生物的作用,可溶性微生物代谢副产物峰明显增强。同时,CW-50的峰C出现红移,表明某些官能团(如羰基、羟基、氨基和羧基)的含量增多。TB-EPS主要为芳香族类蛋白、类色氨酸物质和类可溶性微生物副产物,并未发现类胡敏酸物质。TB-EPS的组成成分未发生显著变化,可能是因为其位于内层,在LB-EPS的保护下未受到大的影响。这进一步说明,EPS的主要组分受到了ZnO NPs尺寸效应的影响。

-

1)微生物群落丰度和多样性差异分析。通过Illumina MiSeq平台测序,进一步考察了不同粒径的ZnO NPs对微生物群落结构和多样性影响。如表3所示,4组样本在最低测序深度序列量为95%的条件下,测序深度指数稳定在0.995~0.998,说明测序已检测绝大多数物种。通过Chao1和物种指数评价微生物群落丰富度,其大小顺序为CW-15>CW-50>CW-对照>CW-90。Simpson和Shannon指数常用于评估微生物多样性[33]。投加ZnO NPs后可刺激微生物产生应激反应,从而促进微生物多样性地增加[34]。在4个反应器中,CW-15中Simpson和Shannon指数均最低。这说明小粒径的ZnO NPs会对微生物产生更强的毒性,降低微生物群落结构多样性[35],从而影响系统的稳定性。

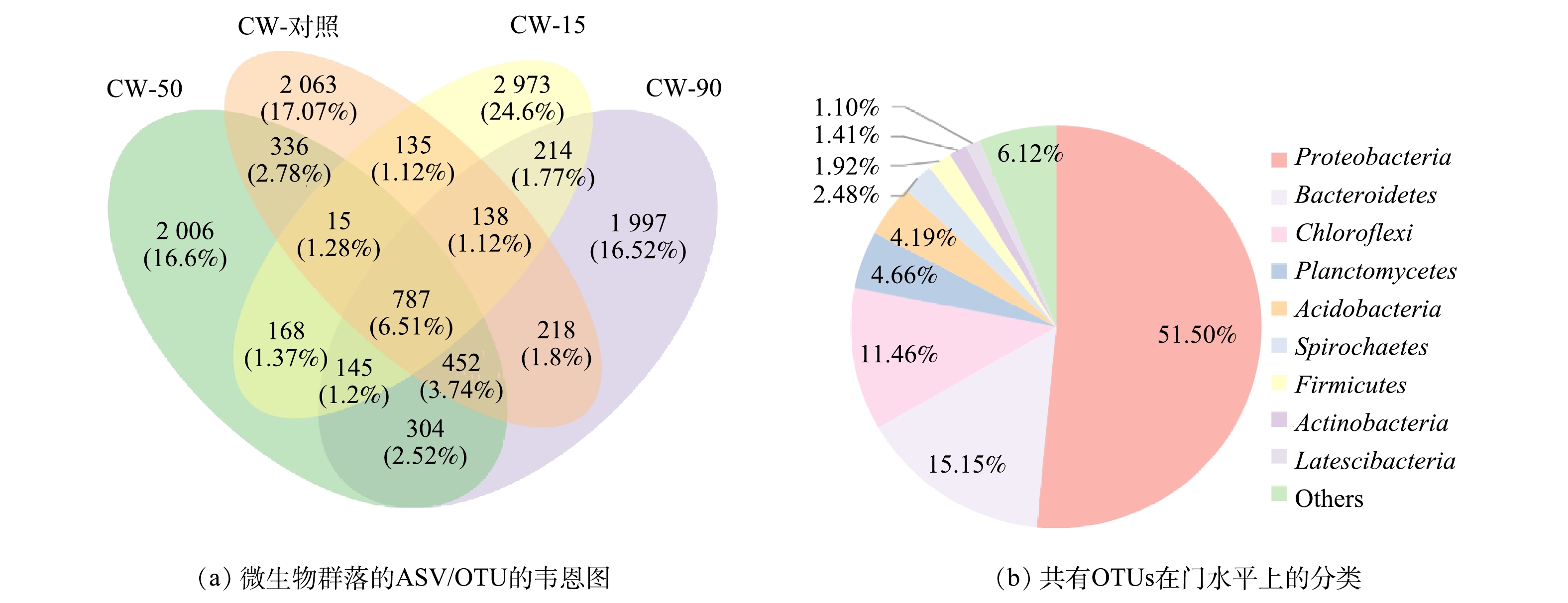

如图5(a)所示,4组样品的总OTUs为12 085个,其中共有787个,占总OTUs的6.51%。如图5(b)所示,4组样品共有的OTUs中微生物中最优势菌门为变形菌门(Proteobacteria)相对丰度占微生物总量的51.50%,其次是拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、绿弯杆菌门(Chloroflexi)、浮霉菌门(Planctomycetes)和放线菌门(Acidobacteria),占微生物总量的比例依次为15.15%、11.46%、4.66%和4.19%。CW-对照、CW-15、CW-50、CW-90中独有的OTUs分别为2 006、2 063、2 973和1 997个,说明不同粒径的ZnO NPs对微生物群落产生了差异性的影响。有研究[36]表明,Proteobacteria、Bacteroidetes、Chloroflexi和Acidobacteria为CWs底泥中的优势菌种。Proteobacteria中大多为革兰氏阴性菌,为兼性或专性厌氧菌,参与厌氧消化反应和氮的循环[37-38]。Bacteroidetes专性厌氧,可以降解纤维素、淀粉、蛋白质和脂类等大分子有机物,并参与自养反硝化[39]。此外,Proteobacteria和Bacteroidetes能够分泌脂多糖,有助于微生物粘附到生物载体表面[40]。因此,短期暴露于不同粒径的ZnO NPs会影响Proteobacteria、Bacteroidetes的丰度,这也是导致CWs中COD、

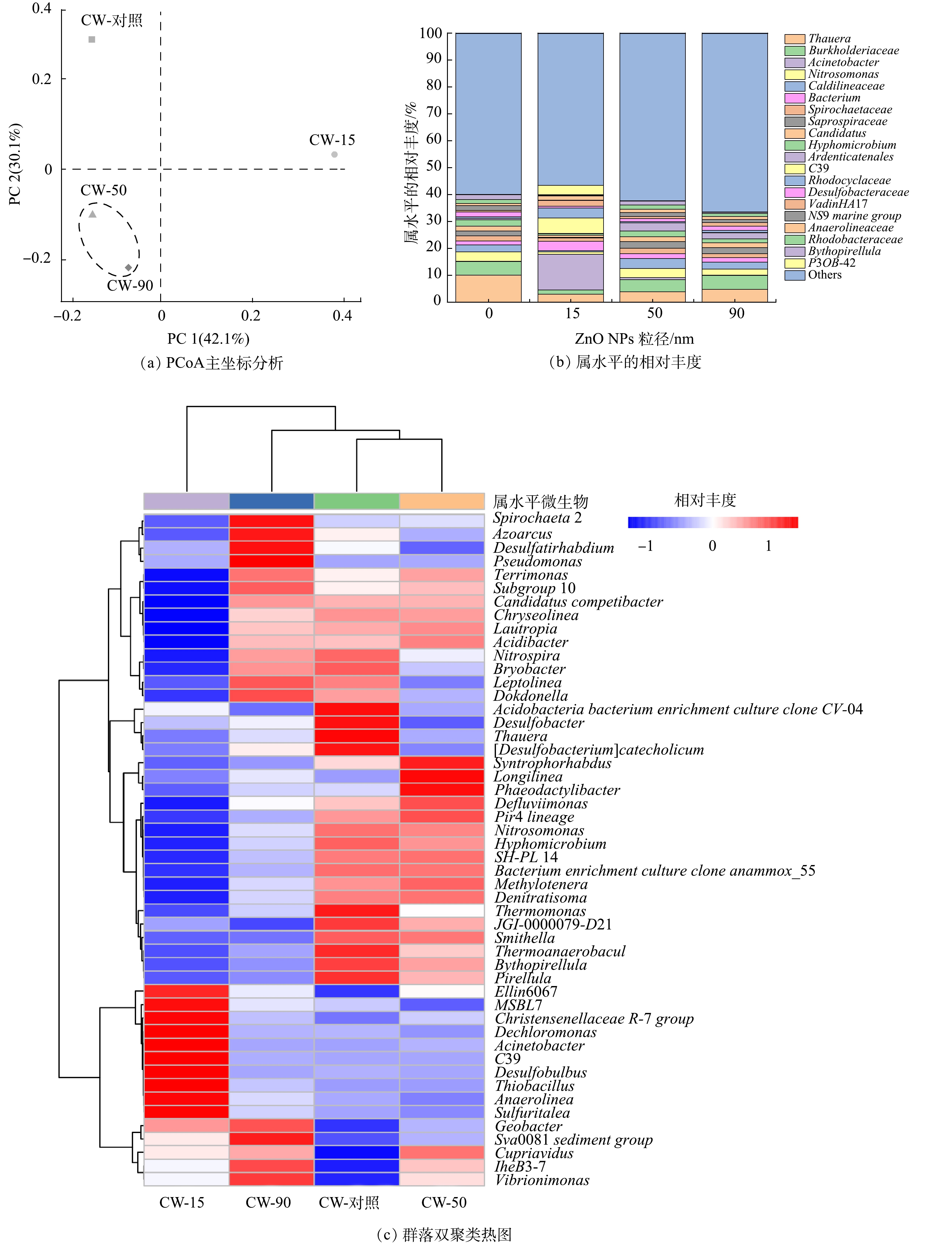

NH+4 -N和TN的去除率降低和EPS含量增加的主要影响因素之一。PCoA是基于Unweighted UniFrac距离指标来考察物种间进化距离和多样性相异系数,其值越小进化距离和差异性越小。如图6(a)所示,主成分1和主成分2分别占微生物群落结构变异的42.10%和30.10%。CW-50和CW-90之间的多样性差异性最小,二者分别与CW-15和CW-对照相比,多样性存在明显差异,说明不同粒径的ZnO NPs导致微生物群落多样性之间存在一定差异性。

为了更好地了解不同粒径的ZnO NPs对CWs系统内微生物群落结构的影响,对4个样本进行了属水平的分析(图6(b))。属水平微生物相对丰度中Thauera、Burkholderiaceae、Acinetobacter和Nitrosomonas为优势菌属。CWs系统脱氮主要通过硝化作用、反硝化作用和氨化作用等协同实现[41]。硝化菌属主要为Acinetobacter、Nitrosomonas和Candidatus,在4个系统(CW-对照、CW-15、CW-50和CW-90)中所占比例分别为14.18%、10.05%和6.44%,反硝化菌属主要包括Thauera、Burkholderiaceae和Caldilineaceae,在4个系统中所占比例分别为21.34%、16.47%和9.37%。其中Thauera是广泛存在的自养和异养反硝化的功能菌[42-43],尽管在高C/N的进水条件下异养反硝化菌占绝对优势,但ZnO NPs对Thauera有明显抑制作用,因而进一步抑制了CWs的反硝化效果。Acinetobacter具有脱氮除磷功能[44-45],能在异养硝化去除NH4+-N的同时实现磷的去除[46-47]。CW-15中Acinetobacter的相对丰度较对照组增加了13.12%,显示出良好的除磷能力。4个系统内反硝化菌属的相对丰度显著高于硝化菌属,故可推测,硝化过程可能为CWs脱氮的主要限制性因素[48]。在进水C/N较高的条件下,微生物分泌大量的EPS导致基质层渗透系数降低,在系统中产生缺氧或厌氧环境,从而有利于异养反硝化菌的生长,硝化菌属活性则受到抑制。此外,ZnO NPs及其释放的Zn2+会引起微生物体内活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS)的增加,引起细胞膜的损伤[49-50],从而降低CWs系统的脱氮性能。

由属水平热图聚类结果可知,样本中含有的菌群丰度差异性(图6(c))。CW-对照与CW-50的物种组成相似性较高,而与CW-15的差异性最大。不同粒径的ZnO NPs均降低了Thauera、Desulfobacter和Thermomonas的相对丰度,使其变成非优势菌。同时,CW-15中优势微生物群落组成相比于其他组差异性较大,其中Acinetobacter、C39和Desulfobulbus等10种优势菌属具有较高的相对丰度,这些优势菌对15 nm的ZnO NPs表现出极大的耐受性,但在50 nm和90 nm ZnO NPs存在的条件下受到不同程度的抑制。投加不同粒径的ZnO NPs后,CWs中微生物群落的变化导致其性能也有所不同。

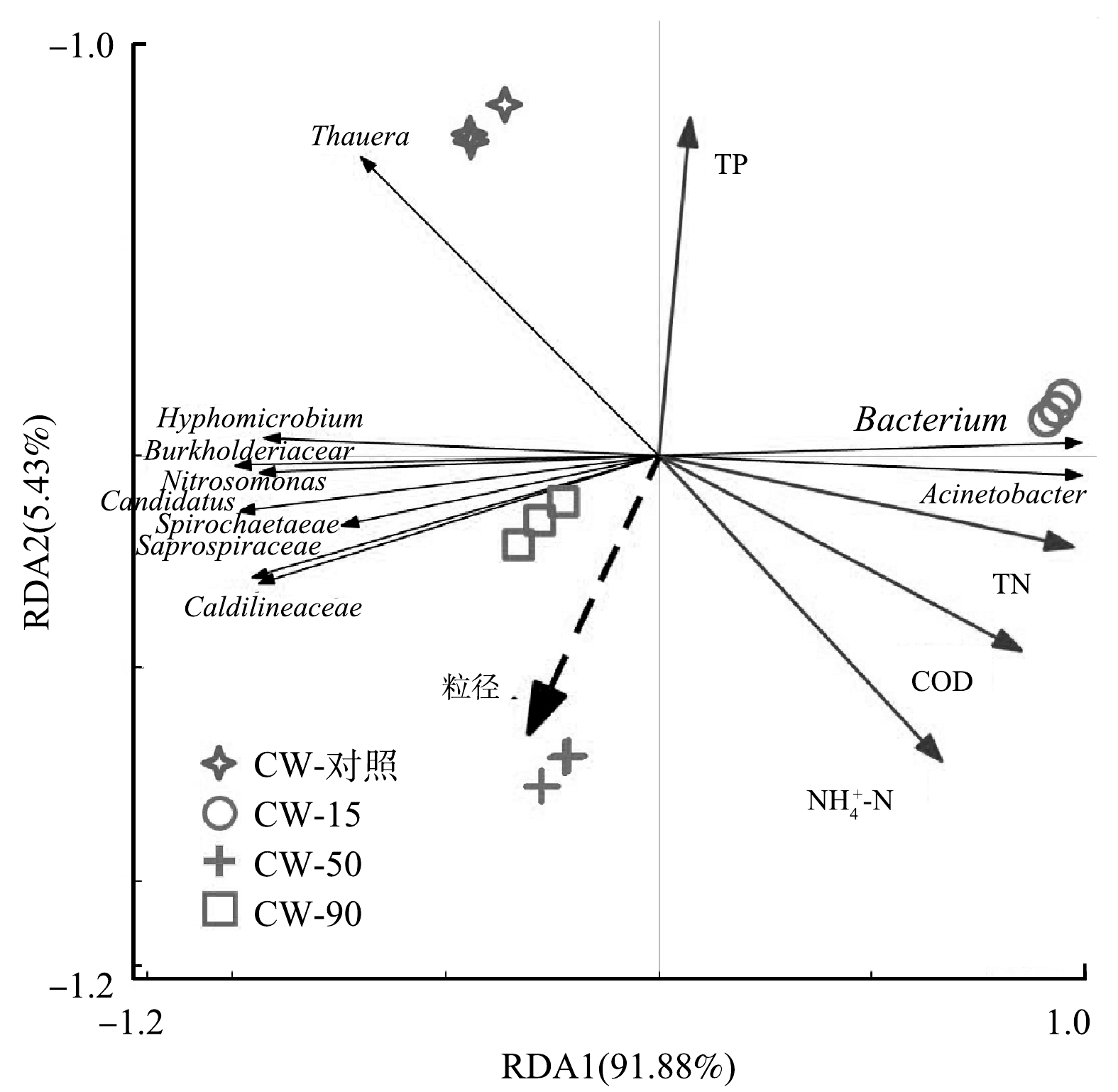

2)微生物与环境因子的关系。如图7所示,RDA反映了属水平微生物与环境因子各组分之间的关系。根据蒙特卡洛置换检验,结果具有统计学意义(P<0.05)[51],且第1与第2坐标轴的方差解释率占总方差的97.31%。由图7可以看出,ZnO NPs的粒径与Caldilineaceae、Spirochaetaceae、Saprospiraceae、Candidatus、Nitrosomonas、Burkholderiaceae和Hyphomicrobium均呈正相关,与Caldilineaceae的相关性最大。COD、

NH+4 -N、TN和TP与上述关系相反。因此,ZnO NPs的粒径效应对属水平微生物的相对丰度有着不同程度的影响。 -

1) ZnO NPs(10.00 mg·L−1)对COD、

NH+4 -N和TN的去除具有明显的粒径效应,其粒径越小,对去除效果的抑制作用越明显;而ZnO NPs(10.00 mg·L−1)对TP的去除有促进作用,粒径越大,其促进效果越明显。2) ZnO NPs粒径越小,刺激微生物分泌EPS的量越多,CWs的渗透系数下降越明显;同时,ZnO NPs对LB-EPS和TB-EPS的含量和组成成分产生了不同程度的影响,15 nm的ZnO NPs对类蛋白质物质有明显抑制作用。

3)短期暴露于不同粒径的ZnO NPs后,CWs中微生物群落结构和多样性可产生显著的差异性;前10种属水平的优势菌属中,与粒径呈正相关的菌属占比为70%。

纳米氧化锌粒径效应对人工湿地运行性能的影响

Size-dependent effects of ZnO nanoparticles on operational performance of constructed wetlands

-

摘要: 为考察ZnO NPs粒径效应对人工湿地运行性能的影响,在进水COD约为216.00 mg·L-1、总氮约为11.10 mg·L−1和总磷约为3.84 mg·L−1的条件下连续运行126 d,对暴露于不同粒径ZnO NPs(10.00 mg·L−1)的人工湿地脱氮除磷性能、填料渗透系数、胞外聚合物(extracellular polymeric substances,EPS)产量和特性以及微生物群落结构和多样性的变化进行了研究。结果表明:与对照组(未投加ZnO NPs)相比,进水中投加15、50和90 nm ZnO NPs后,人工湿地对COD的去除率分别下降了8.73%、7.55%和6.97%;氨氮和总氮的去除率分别下降了21.96%和10.95%、17.75%和10.00%以及15.34%和3.78%。高通量测序结果表明,ZnO NPs粒径越小,对硝化菌属Thauera的抑制作用越明显。投加ZnO NPs后,其释放的Zn2+会与水中磷酸盐结合生成磷酸锌等不溶物,同时会增加异养硝化菌Acinetobacter的相对丰度,从而导致总磷的去除率比对照组提高了42.49%~56.38%。此外,与对照组(97.18 mg·g−1)相比,投加15、50和90 nm的ZnO NPs后EPS的产量分别增加到212.97、156.30和128.53 mg·g−1。EPS分泌量的增大,导致填料渗透系数快速降低,在运行83 d后分别下降了71.17%、67.83%和37.50%。Abstract: ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) have catalytic activity, strong oxidability and high stability, which are widely used in semiconductors, dyes, plastic additives, cosmetics and many other fields. The life cycle of the ZnO NPs series of products, will inevitably cause damage to the environment, thus affect the sewage disposal system. laboratory scale horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands were operated for 126 days when influent chemical oxygen demand (COD), total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP) were about 216.00 mg·L−1, 11.10 mg·L−1 and 3.84 mg·L−1, respectively. To investigate the size-dependent effects of ZnO NPs on the operational performance of constructed wetlands, the nitrogen, and phosphorus removal performance, the permeability coefficient of fillers, the content and characteristics of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), as well as the change in microbial community structure and diversity after exposure to different particle sizes of ZnO NPs (10.00 mg·L−1) were studied. The results indicated that compared with the control group, the removal efficiencies of COD in the constructed wetlands exposed to 15 nm, 50 nm, and 90 nm of ZnO NPs decreased by 8.73%, 7.55%, and 6.97%, respectively, meanwhile the removal efficiencies of NH4+-N and TN decreased by 21.96% and 10.95%, 17.75% and 10.00%, and 15.34%, and 3.78%, respectively. High throughput sequencing indicated that the smaller ZnO NPs size, the more significant inhibitory effect on nitrification bacterium (e.g. Thauera). After adding ZnO NPs, the released Zn2+ could combine with phosphate in water to form insoluble substances such as zinc phosphate precipitation, and the relative abundance of the heterotrophic nitrifying bacterium (e.g. Acinetobacter) also increased, which resulted in the increase of TP removal efficiencies by 42.49%~56.38% in comparison with the control group. In addition, compared with the control group (97.18 mg·g−1), the EPS contents when exposing to 15 nm, 50 nm, and 90 nm of ZnO NPs increased to 212.97 mg·g−1, 156.30 mg·g−1, and 128.53 mg·g−1, respectively. The increasing EPS contents led to a rapid decrease of the permeability coefficient of fillers by 71.17%, 67.83%, and 37.50% at 83 days, respectively.

-

Key words:

- ZnO nanoparticles /

- size-dependent effect /

- constructed wetlands /

- clogging /

- microbial community

-

纳米氧化锌(ZnO nanoparticles,ZnO NPs)具有催化活性、强氧化性和高稳定性,广泛应用于半导体、染料、塑料添加剂、化妆品等许多领域[1]。在ZnO NPs系列产品的生命周期中,其不可避免地会进入生态系统[2],由其引发的生物安全性问题,引起了学者们的广泛关注[3]。近年来,在土壤、污水和污泥中均发现了ZnO NPs的存在。GOTTSCHALK等[4]通过建模模拟得出,欧洲和美国水环境中的ZnO NPs质量浓度分别为0.432 mg·L−1和0.3 mg·L−1,已达到损害水体生物的阈值。部分进入环境中的ZnO NPs最终会进入到污水处理系统中[5]。因此,有必要了解ZnO NPs对污水生物处理运行效果的影响。

人工湿地(constructed wetlands,CWs)具有运行成本低、无二次污染、景观价值高等优点,已广泛应用于污水处理中[6-7]。然而,在其长期运行过程中,基质表面会堆积大量的难降解有机物和微生物分泌的胞外聚合物(extracellular polymeric substances,EPS),同时EPS会吸附无机颗粒和有机物并形成致密的堵塞层,造成CWs的堵塞[8]。有研究表明,ZnO NPs溶解产生的Zn2+以及NPs的内化会损伤细胞[9-10],且其粒径越小,生物毒性越强[11],会刺激微生物产生更多的EPS[12]。EPS亲水组分可通过吸附ZnO NPs,降低其对微生物的生物毒性[13-14]。然而,大量的EPS粘附于基质表面,可能会降低基质层孔隙率[15-16],从而降低CWs的使用寿命。目前,有关ZnO NPs的粒径效应对CWs性能及堵塞的影响尚缺乏系统的研究,并且ZnO NPs的粒径与微生物相对丰度的关系尚未明确。

针对上述问题,本研究考察了3种不同粒径(15 nm、50 nm和90 nm)的ZnO NPs对CWs性能、渗透系数及EPS产量和特性的影响,探讨了微生物群落结构和多样性对不同粒径ZnO NPs的响应,以期为CWs的稳定运行提供参考。

1. 材料与方法

1.1 ZnO NPs悬浊液配制

称取0.5 g ZnO NPs(表1)于1 L超纯水中,用磁力搅拌器混合搅拌30 min后,装入棕色试剂瓶中。在25 ℃下,超声1 h[17],制得ZnO NPs悬浊液。使用前,悬浊液需超声1 h(25 ℃,500 W,40 kHz),防止ZnO NPs团聚。

表 1 ZnO NPs基本参数Table 1. Basic parameters of ZnO NPs粒径/nm 颜色、状态 纯度/% 比表面积/(m2·g−1) 生产厂家 15 白色粉末 99.9 110 南京埃普瑞纳米材料有限公司 50 淡黄色/白色粉末 99.8 15~30 杭州万景新材料有限公司 90 淡黄色/白色粉末 99.8 10~20 杭州万景新材料有限公司 1.2 实验装置

构建4组实验室规模的水平潜流人工湿地系统(horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland,HSFCWs),具体构造见图1。CWs反应器为PP材质(长、宽、高分别为26.5、26.5、37 cm)自下而上分别为2 cm细沙、17 cm砾石(粒径约10~30 mm)、细丝网(80 目)、8 cm 细沙和9株高约30 cm、生长状态均一的香蒲。为保证实验结果稳定可靠,在种入反应器前,先将香蒲放入内有1/4浓度的霍格兰氏植物培养液的塑料箱中,在25 ℃下培养驯化10 d左右。

1.3 接种污泥和进水水质

分别以乙酸钠、氯化铵、磷酸二氢钾和磷酸氢二钾作为碳源、氮源和磷源配制人工污水,其COD、TN和TP分别约为216.00、11.10和3.84 mg·L−1。配水中添加1.00 mL·L−1微量元素,包括0.83 mg·L−1 KI、6.20 mg·L−1 硼酸、22.30 mg·L−1 MnSO4、8.60 mg·L−1 ZnSO4、0.025 mg·L−1 CuSO4、0.025 mg·L−1 CoCl2、5.56 g·L−1 FeSO4·7H2O和7.46 g·L−1 EDTA。使用1 mol·L−1盐酸或氢氧化钠调节进水pH在7.4左右。反应器进水为下进上出,水力停留时间(HRT)为2 d。

在填充到反应器前,利用青岛市李村河污水处理厂二沉池回流污泥作为接种污泥对砾石进行挂膜。将砾石没入污泥中,闷曝3 d,然后以人工污水作为进水,连续运行15 d左右。待砾石表面附着生物膜后,将其填入反应器内,每日投配定量人工污水。在运行过程中,测定COD、TP、

NH+4 1.4 水质指标测定方法

实验期间,每隔1 d对4个反应器的进出水进行取样,利用重铬酸钾法测定COD,纳氏试剂分光光度法测定

NH+4 1.5 水力传导性测量方法

CWs反应器连续进水,并处于饱和状态。采用常水头渗透系数法[19],测定CWs整体基质层的渗透系数,根据式(1)进行计算。

K=QLA(ΔH+L)t (1) 式中:K为渗透系数,cm·s−1;Q为单位时间水渗透量,mL·s−1;ΔH为水头损失,cm,ΔH=H1−H2;A为过水断面面积,cm2;L为渗透路径长度,cm;t为实验持续时间,s。

1.6 EPS提取和分析方法

1) EPS提取和测定。待反应器停止运行后,从CWs顶部基质层收集20.0 g填料,用100 mL的NaCl(0.9%)溶液冲洗后,将得到的滤液倒入已灼烧至恒重的坩埚中在105 ℃下蒸干,然后再放入马弗炉在600 ℃下烧灼3 h,最后等坩埚冷却至恒重后测定堵塞物的质量。EPS采用改进的加热法进行提取[20],取40 mL的堵塞物混合液于4 000 r·min−1离心5 min,倒掉上清液后加入NaCl(0.05%,70 ℃)溶液至40 mL,混匀后于4 000 r·min−1离心10 min,所得上清液用0.45 µm的聚醚砜膜过滤后即为疏松附着型胞外聚合物(loosely bound EPS,LB-EPS);取LB-EPS离心后的沉淀物,加入NaCl(0.05%,60 ℃)溶液至40 mL,充分混合后在100 ℃下加热30 min,于4 000 r·min−1离心10 min,所得上清液用0.45 µm的聚醚砜膜过滤后即为紧密结合型胞外聚合物(tightly bound EPS,TB-EPS)。LB-EPS和TB-EPS中蛋白质(proteins,PN)和多糖(polysaccharides,PS)的含量分别通过Folin比色法[21]和蒽酮-硫酸比色法[22]测定。

2)三维荧光光谱分析。采用荧光分光光度计(日立F-4600)测定LB-EPS和TB-EPS的三维荧光激发发射矩阵光谱(3D-EEM)。以蒸馏水作为空白对照,测定参数设置如下:激发波长(Ex)为200~400 nm,扫描间隔5 nm;发射波长(Em)为200~500 nm,扫描间隔为5 nm;激发光和发射光的狭缝均为10 nm,扫描速度为2 400 nm·min−1[23]。

1.7 16S rRNA高通量测序及结果分析

实验结束后,采集每个反应器不同高度的基质约100.00 g,混合后放入磷酸盐缓冲溶液中(10 mmol·L−1 Na2HPO4,8.50 g·L−1 NaCl),在超声波清洗机中(KQ-500B)处理5 min,然后涡漩1 min,将微生物从填料表面分离到溶液中。经离心处理后,微生物样品送往上海派森诺生物科技有限公司进行Illumina MiSeq/NovaSeq高通量测序。

1.8 数据分析

实验数据统计分析采用SPSS 23.0软件进行方差齐性检验和单因素方差分析(采用邓肯多量程检验,P<0.05视为具有显著性差异);采用Canoco 5软件进行冗余分析(redundancy analysis,RDA)研究微生物群落和环境因子之间的关系;采用Matlab 2018a软件绘制3D-EEM光谱图,去除拉曼散射和瑞利散射,并进行归一化处理;采用OriginLab 2021和R语言(4.0.4)绘图及数据分析。

2. 结果与讨论

2.1 ZnO NPs粒径对CWs处理性能的影响

系统稳定运行45 d后,在进水中投加10.00 mg·L−1不同粒径的ZnO NPs悬浊液。如图2(a)所示,在投加10.00 mg·L−1不同粒径的ZnO NPs前,CW-对照、CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对COD的去除率分别为88.70%、91.40%、92.47%和95.01%;投加ZnO NPs 39 d后,与不加ZnO NPs的空白对照组相比,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对COD的平均去除率均有不同程度的下降,分别为8.73%、7.55%和6.97%。这表明较小粒径的ZnO NPs对COD的去除产生较明显的抑制作用。其原因可能归结于以下2点:ZnO NPs(10.00 mg·L−1)释放出的Zn2+离子具有生物毒性,导致异养微生物对COD的去除率下降[24];小粒径ZnO NPs与微生物细胞具有更大的接触面积[25],对异养微生物的生物代谢抑制更加明显,从而降低COD的去除率。

如图2(b)所示,在投加ZnO NPs 28 d后,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对

NH+4 NH+4 NH+4 NH+4 如图2(c)所示,投加ZnO NPs后,CW-对照、CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对TN的去除率呈现先增加后降低的趋势。这可能是因为:反应前期ZnO NPs释放的低浓度的Zn2+会提高厌氧氨氧化菌(anaerobic-oxidizing bacteria,AOB)的代谢活性,从而消耗反应器中剩余的亚硝酸盐,降低了TN的浓度[26]。然而,在投加ZnO NPs 24 d后,与空白对照组相比,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对TN的去除率分别下降了10.95%、10.00%和3.78%。

如图2(d)所示,在投加ZnO NPs 18 d后,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90对TP的去除率有不同程度的增加,分别为42.49%、52.34%和56.38%。可以推测,随着堵塞的发生,基质中积累的EPS作为堵塞物的关键成分,引入了大量的磷吸附位点。此外,ZnO NPs释放的Zn2+与磷酸盐反应生成磷酸锌等络合物,也会抑制磷酸盐的释放[12],从而提高了CWs的除磷性能。

2.2 ZnO NPs粒径对CWs堵塞的影响

1) CWs渗透系数的变化。进水中连续投加不同粒径的ZnO NPs,稳定运行83 d后,4个CWs发生了不同程度的堵塞。如表2所示,CW-对照组的渗透系数维持在1.20×10−3 cm·s−1,而CW-15、CW-50和CW-90基质层的渗透系数明显变小,分别比CW-对照降低了71.17%、67.83%和37.50%。随着ZnO NPs在CWs中的累积,导致系统水流阻力增大,出现短流、返混等现象,从而缩短HRT。同时,CWs处理性能的下降导致营养物质不断积累,再加上ZnO NPs刺激微生物产生的EPS不断增多,加剧了堵塞的程度。

表 2 不同粒径的ZnO NPs短期暴露对CWs渗透系数的影响Table 2. Effect of short-term exposure of ZnO NPs with different particle sizes on permeability coefficient of CWsZnO NPs 粒径/nm 堵塞实验后渗透系数K/(cm·s−1) 运行83 d 运行86 d 运行89 d 空白 1.20×10−3 1.20×10−3 1.20×10−3 15 3.50×10−4 3.44×10−4 3.43×10−4 50 3.88×10−4 3.85×10−4 3.85×10−4 90 7.52×10−4 7.50×10−4 7.48×10−4 2) EPS和PN和PS产量的变化。有研究[27]表明,当微生物暴露于ZnO NPs等有毒物质下会产生应激反应并促进EPS的分泌。污泥絮体表面的EPS可以吸附ZnO NPs颗粒从而阻止其扩散到微生物中[28]。如图3(a)所示,与对照组(97.18 mg·g−1)相比,CW-15、CW-50和CW-90中的EPS分别增加到212.97、156.30和128.53 mg·g−1。15 nm的ZnO NPs可刺激微生物分泌EPS的量最多,这主要是因为小粒径的ZnO NPs比表面积大,更易于与微生物接触。有研究[29]表明,8 nm的ZnO NPs对金黄色葡萄球菌生长的抑制性强于50~70 nm ZnO NPs。此外,溶出的Zn2+会损伤细胞膜和DNA结构,可进一步诱导微生物持续分泌EPS[30]。

EPS主要由PN、PS以及少量核酸和脂质组成[12]。短期暴露于不同粒径的ZnO NPs后,LB-EPS(图3(b))和TB-EPS(图3(c))中PN和PS含量显著升高,尤以CW-15最为显著。这主要是因为小粒径的ZnO NPs毒性更强,易刺激微生物分泌更多的EPS。此外,ZnO NPs的短期暴露可能导致了大量生物量衰减和大量细胞破裂[31],从而使PN和PS含量大幅增加。

3) LB-EPS和TB-EPS主要组分分析。由图4可以看出,投加ZnO NPs前后LB-EPS和TB-EPS中识别出4个特征峰(峰A~D),其中峰A(200 nm/290~300 nm)为芳香族类蛋白物质,峰B(220~230 nm/300~330 nm)为类色氨酸物质,峰C(270~280 nm/300~330 nm)为类可溶性微生物副产物,而峰D(270 nm/420 nm)为类胡敏酸物质[32]。CW-对照和CW-15的LB-EPS主要为芳香族类蛋白和类胡敏酸物质,CW-50和CW-90的LB-EPS中峰D被峰C取代,这说明由于微生物的作用,可溶性微生物代谢副产物峰明显增强。同时,CW-50的峰C出现红移,表明某些官能团(如羰基、羟基、氨基和羧基)的含量增多。TB-EPS主要为芳香族类蛋白、类色氨酸物质和类可溶性微生物副产物,并未发现类胡敏酸物质。TB-EPS的组成成分未发生显著变化,可能是因为其位于内层,在LB-EPS的保护下未受到大的影响。这进一步说明,EPS的主要组分受到了ZnO NPs尺寸效应的影响。

2.3 ZnO NPs粒径对微生物群落丰度和多样性的影响

1)微生物群落丰度和多样性差异分析。通过Illumina MiSeq平台测序,进一步考察了不同粒径的ZnO NPs对微生物群落结构和多样性影响。如表3所示,4组样本在最低测序深度序列量为95%的条件下,测序深度指数稳定在0.995~0.998,说明测序已检测绝大多数物种。通过Chao1和物种指数评价微生物群落丰富度,其大小顺序为CW-15>CW-50>CW-对照>CW-90。Simpson和Shannon指数常用于评估微生物多样性[33]。投加ZnO NPs后可刺激微生物产生应激反应,从而促进微生物多样性地增加[34]。在4个反应器中,CW-15中Simpson和Shannon指数均最低。这说明小粒径的ZnO NPs会对微生物产生更强的毒性,降低微生物群落结构多样性[35],从而影响系统的稳定性。

表 3 不同粒径的ZnO NPs短期暴露下微生物群落的丰富度和多样指数Table 3. Richness and diversity index of the microbial community after short-term exposure of ZnO NPs with different particle sizes粒径/nm Chao1指数 物种指数 Simpson指数 Shannon指数 测序深度指数 对照 4 359.01 4 280.9 0.992 9.326 0.996 15 4 740.83 4 707.9 0.980 9.183 0.998 50 4 488.43 4 357.2 0.995 9.434 0.995 90 4 302.15 4 253.5 0.996 9.750 0.997 如图5(a)所示,4组样品的总OTUs为12 085个,其中共有787个,占总OTUs的6.51%。如图5(b)所示,4组样品共有的OTUs中微生物中最优势菌门为变形菌门(Proteobacteria)相对丰度占微生物总量的51.50%,其次是拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、绿弯杆菌门(Chloroflexi)、浮霉菌门(Planctomycetes)和放线菌门(Acidobacteria),占微生物总量的比例依次为15.15%、11.46%、4.66%和4.19%。CW-对照、CW-15、CW-50、CW-90中独有的OTUs分别为2 006、2 063、2 973和1 997个,说明不同粒径的ZnO NPs对微生物群落产生了差异性的影响。有研究[36]表明,Proteobacteria、Bacteroidetes、Chloroflexi和Acidobacteria为CWs底泥中的优势菌种。Proteobacteria中大多为革兰氏阴性菌,为兼性或专性厌氧菌,参与厌氧消化反应和氮的循环[37-38]。Bacteroidetes专性厌氧,可以降解纤维素、淀粉、蛋白质和脂类等大分子有机物,并参与自养反硝化[39]。此外,Proteobacteria和Bacteroidetes能够分泌脂多糖,有助于微生物粘附到生物载体表面[40]。因此,短期暴露于不同粒径的ZnO NPs会影响Proteobacteria、Bacteroidetes的丰度,这也是导致CWs中COD、

NH+4 PCoA是基于Unweighted UniFrac距离指标来考察物种间进化距离和多样性相异系数,其值越小进化距离和差异性越小。如图6(a)所示,主成分1和主成分2分别占微生物群落结构变异的42.10%和30.10%。CW-50和CW-90之间的多样性差异性最小,二者分别与CW-15和CW-对照相比,多样性存在明显差异,说明不同粒径的ZnO NPs导致微生物群落多样性之间存在一定差异性。

为了更好地了解不同粒径的ZnO NPs对CWs系统内微生物群落结构的影响,对4个样本进行了属水平的分析(图6(b))。属水平微生物相对丰度中Thauera、Burkholderiaceae、Acinetobacter和Nitrosomonas为优势菌属。CWs系统脱氮主要通过硝化作用、反硝化作用和氨化作用等协同实现[41]。硝化菌属主要为Acinetobacter、Nitrosomonas和Candidatus,在4个系统(CW-对照、CW-15、CW-50和CW-90)中所占比例分别为14.18%、10.05%和6.44%,反硝化菌属主要包括Thauera、Burkholderiaceae和Caldilineaceae,在4个系统中所占比例分别为21.34%、16.47%和9.37%。其中Thauera是广泛存在的自养和异养反硝化的功能菌[42-43],尽管在高C/N的进水条件下异养反硝化菌占绝对优势,但ZnO NPs对Thauera有明显抑制作用,因而进一步抑制了CWs的反硝化效果。Acinetobacter具有脱氮除磷功能[44-45],能在异养硝化去除NH4+-N的同时实现磷的去除[46-47]。CW-15中Acinetobacter的相对丰度较对照组增加了13.12%,显示出良好的除磷能力。4个系统内反硝化菌属的相对丰度显著高于硝化菌属,故可推测,硝化过程可能为CWs脱氮的主要限制性因素[48]。在进水C/N较高的条件下,微生物分泌大量的EPS导致基质层渗透系数降低,在系统中产生缺氧或厌氧环境,从而有利于异养反硝化菌的生长,硝化菌属活性则受到抑制。此外,ZnO NPs及其释放的Zn2+会引起微生物体内活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS)的增加,引起细胞膜的损伤[49-50],从而降低CWs系统的脱氮性能。

由属水平热图聚类结果可知,样本中含有的菌群丰度差异性(图6(c))。CW-对照与CW-50的物种组成相似性较高,而与CW-15的差异性最大。不同粒径的ZnO NPs均降低了Thauera、Desulfobacter和Thermomonas的相对丰度,使其变成非优势菌。同时,CW-15中优势微生物群落组成相比于其他组差异性较大,其中Acinetobacter、C39和Desulfobulbus等10种优势菌属具有较高的相对丰度,这些优势菌对15 nm的ZnO NPs表现出极大的耐受性,但在50 nm和90 nm ZnO NPs存在的条件下受到不同程度的抑制。投加不同粒径的ZnO NPs后,CWs中微生物群落的变化导致其性能也有所不同。

2)微生物与环境因子的关系。如图7所示,RDA反映了属水平微生物与环境因子各组分之间的关系。根据蒙特卡洛置换检验,结果具有统计学意义(P<0.05)[51],且第1与第2坐标轴的方差解释率占总方差的97.31%。由图7可以看出,ZnO NPs的粒径与Caldilineaceae、Spirochaetaceae、Saprospiraceae、Candidatus、Nitrosomonas、Burkholderiaceae和Hyphomicrobium均呈正相关,与Caldilineaceae的相关性最大。COD、

NH+4 3. 结论

1) ZnO NPs(10.00 mg·L−1)对COD、

NH+4 2) ZnO NPs粒径越小,刺激微生物分泌EPS的量越多,CWs的渗透系数下降越明显;同时,ZnO NPs对LB-EPS和TB-EPS的含量和组成成分产生了不同程度的影响,15 nm的ZnO NPs对类蛋白质物质有明显抑制作用。

3)短期暴露于不同粒径的ZnO NPs后,CWs中微生物群落结构和多样性可产生显著的差异性;前10种属水平的优势菌属中,与粒径呈正相关的菌属占比为70%。

-

表 1 ZnO NPs基本参数

Table 1. Basic parameters of ZnO NPs

粒径/nm 颜色、状态 纯度/% 比表面积/(m2·g−1) 生产厂家 15 白色粉末 99.9 110 南京埃普瑞纳米材料有限公司 50 淡黄色/白色粉末 99.8 15~30 杭州万景新材料有限公司 90 淡黄色/白色粉末 99.8 10~20 杭州万景新材料有限公司 表 2 不同粒径的ZnO NPs短期暴露对CWs渗透系数的影响

Table 2. Effect of short-term exposure of ZnO NPs with different particle sizes on permeability coefficient of CWs

ZnO NPs 粒径/nm 堵塞实验后渗透系数K/(cm·s−1) 运行83 d 运行86 d 运行89 d 空白 1.20×10−3 1.20×10−3 1.20×10−3 15 3.50×10−4 3.44×10−4 3.43×10−4 50 3.88×10−4 3.85×10−4 3.85×10−4 90 7.52×10−4 7.50×10−4 7.48×10−4 表 3 不同粒径的ZnO NPs短期暴露下微生物群落的丰富度和多样指数

Table 3. Richness and diversity index of the microbial community after short-term exposure of ZnO NPs with different particle sizes

粒径/nm Chao1指数 物种指数 Simpson指数 Shannon指数 测序深度指数 对照 4 359.01 4 280.9 0.992 9.326 0.996 15 4 740.83 4 707.9 0.980 9.183 0.998 50 4 488.43 4 357.2 0.995 9.434 0.995 90 4 302.15 4 253.5 0.996 9.750 0.997 -

[1] ZHENG X, WU R, CHEN Y G. Effects of ZnO nanoparticles on wastewater biological nitrogen and phosphorus removal[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(7): 2826-2832. [2] ZHANG Z Z, CHENG Y F, XU L Z J, et al. Transient disturbance of engineered ZnO nanoparticles enhances the resistance and resilience of anammox process in wastewater treatment[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 622-623: 402-409. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.016 [3] SU H, WANG Y F, GU Y L, et al. Potential applications and human biosafety of nanomaterials used in nanomedicine[J]. Journal of Applied Toxicology, 2017, 38: 3-24. [4] GOTTSCHALK F, SONDERER T, SCHOLZ R W, et al. Modeled environmental concentrations of engineered nanomaterials (TiO2, ZnO, Ag, CNT, fullerenes) for different regions[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009, 43(24): 9216-9222. [5] PUAY N Q, QIU G, TING Y P. Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on biological wastewater treatment in a sequencing batch reactor[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2015, 88: 139-145. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.03.081 [6] WU Y H, HAN R, YANG X N, et al. Correlating microbial community with physicochemical indices and structures of a full-scale integrated constructed wetland system[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2016, 100: 6917-6926. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7526-4 [7] 林莉莉, 鲁汭, 肖恩荣, 等. 人工湿地生物堵塞研究进展[J]. 环境科学与技术, 2019, 42(6): 207-214. [8] YE J, LI H, ZHANG C, et al. Classification and extraction methods of the clog components of constructed wetland[J]. Ecological Engineering, 2014, 70: 327-331. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.06.028 [9] FRANKLIN N M, ROGERS N J, APTE S C, et al. Comparative toxicity of nanoparticulate ZnO, bulk ZnO, and ZnCl2 to a freshwater microalga (Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata): Importance of particle solubility[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2007, 41(24): 8484-8490. [10] HE E, QIU R, CAO X, et al. Elucidating toxicodynamic differences at the molecular scale between ZnO NPs and ZnCl2 in enchytraeus crypticus via nontargeted metabolomics[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54: 3487-3498. [11] SILVA B L D, CAETANO B L, CHIARI-ANDRÉO B G, et al. Increased antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles: Influence of size and surface modification[J]. Colloids and Surfaces B:Biointerfaces, 2019, 177: 440-447. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.02.013 [12] WANG S, GAO M C, MA B R, et al. Size-dependent effects of ZnO nanoparticles on performance, microbial enzymatic activity and extracellular polymeric substances in sequencing batch reactor[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 257: 113596. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113596 [13] WEI L L, DING J, XUE M, et al. Adsorption mechanism of ZnO and CuO nanoparticles on two typical sludge EPS: Effect of nanoparticle diameter and fractional EPS polarity on binding[J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 214: 210-219. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.093 [14] KISER M A, RYU H, JANG H Y, et al. Biosorption of nanoparticles to heterotrophic wastewater biomass[J]. Water Research, 2010, 44: 4105-4114. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.05.036 [15] SAMSÓ R, GARCÍA J, MOLLE P, et al. Modelling bioclogging in variably saturated porous media and the interactions between surface/subsurface flows: Application to constructed wetland[J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2016, 165: 271-279. [16] MATOS M D, SPERLING M V, MATOS A D. Clogging in horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands: Influencing factors, research methods and remediation techniques[J]. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology, 2018, 17(1): 87-107. doi: 10.1007/s11157-018-9458-1 [17] KELLER A A, WANG H T, ZHOU D X, et al. Stability and aggregation of metal oxide nanoparticles in natural aqueous matrices[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(6): 1962-1967. [18] 国家环境保护总局. 水和废水监测分析方法[M]. 4版. 北京: 中国环境科学出版社, 2002. [19] ZHAO L F, ZHU W, TONG W. Clogging processes caused by biofilm growth and organic particle accumulation in lab-scale vertical flow constructed wetlands[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2009, 6: 40-47. [20] LI X Y, YANG S F. Influence of loosely bound extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) on the flocculation, sedimentation and dewaterability of activated sludge[J]. Water Research, 2007, 41: 1022-1030. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2006.06.037 [21] MIAO L Z, WANG C, HOU J, et al. Response of wastewater biofilm to CuO nanoparticle exposure in terms of extracellular polymeric substances and microbial community structure[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 579: 588-597. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.056 [22] WANG Z, GAO M, WEI J, et al. Long-term effects of salinity on extracellular polymeric substances, microbial activity and microbial community from biofilm and suspended sludge in an anoxic-aerobic sequencing batch biofilm reactor[J]. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, 2016, 68: 275-280. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2016.09.005 [23] 王雪礁, 王森, 李姗姗, 等. 二氧化钛纳米颗粒对序批式反应器中活性污泥胞外聚合物产量及其组分的影响[J]. 中国海洋大学学报(自然科学版), 2018, 48(4): 111-119. [24] CHEN L, HU Q Z, ZHANG X, et al. Effects of ZnO nanoparticles on the performance of anaerobic membrane bioreactor: An attention to the characteristics of supernatant, effluent and biomass community[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2019, 248: 743-755. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.02.051 [25] SHARIFI S, BEHZADI S, LAURENT S, et al. Toxicity of nanomaterials[J]. Chemical Society Review, 2012, 41(6): 2323-2343. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15188F [26] ZHANG X J, ZHANG N, FU H Q, et al. Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on nitrogen removal, microbial activity and microbial community of CANON process in a membrane bioreactor[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 243: 93-99. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.052 [27] MA B R, LI Z W, WANG S, et al. Insights into the effect of nickel (Ni(II)) on the performance, microbial enzymatic activity and extracellular polymeric substances of activated sludge[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2019, 251: 81-89. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.094 [28] DIMKPA C O, CALDER A, GAJJAR P, et al. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with an environmentally beneficial bacterium, Pseudomonas chlororaphis[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2011, 188(1/2/3): 428-435. [29] JONES N, RAY B, RANJIT K T, et al. Antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticle suspensions on a broad spectrum of microorganisms[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2010(1): 71-76. [30] 郑晓英, 吴颜科, 陈卫, 等. Zn(Ⅱ)长期作用对好氧颗粒污泥脱氮和微生物活性的影响[J]. 水处理技术, 2014, 40(6): 24-28. [31] ZHANG D Q, ENG C Y, STUCKEY D C, et al. Effects of ZnO nanoparticle exposure on wastewater treatment and soluble microbial products (SMPs) in an anoxic-aerobic membrane bioreactor[J]. Chemosphere, 2017, 171: 446-459. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.12.053 [32] CHEN W, WESTERHOFF P, LEENHEER J A, et al. Fluorescence excitation-emission matrix regional integration to quantify spectra for dissolved organic matter[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 37(24): 5701-5710. [33] KONG Q, HE X, MA S S, et al. The performance and evolution of bacterial community of activated sludge exposed to trimethoprim in a sequencing batch reactor[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 244: 872-879. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.08.018 [34] LIN W X, SUN S Y, WU C, et al. Effects of toxic organic flotation reagent (aniline aerofloat) on an A/O submerged membrane bioreactor (sMBR): Microbial community dynamics and performance[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2017, 142: 14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.03.033 [35] GE Y, SCHIMEL J P, HOLDEN P A. Evidence for negative effects of TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles on soil bacterial communities[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(4): 1659-1664. [36] CHEN Y, WEN Y, TANG Z R, et al. Effects of plant biomass on bacterial community structure in constructed wetlands used for tertiary wastewater treatment[J]. Ecological Engineering, 2015, 84: 38-45. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.07.013 [37] WANG Q, LV R Y, RENE E R, et al. Characterization of microbial community and resistance gene (CzcA) shifts in up-flow constructed wetlands-microbial fuel cell treating Zn (II) contaminated wastewater[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2020, 302(18): 122867. [38] JIANG Y, WEI L, YANG K, et al. Rapid formation of aniline-degrading aerobic granular sludge and investigation of its microbial community succession[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2017, 166: 1235-1243. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.134 [39] CHEN D, WANG H, YANG K, et al. Performance and microbial communities in a combined bioelectrochemical and sulfur autotrophic denitrification system at low temperature[J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 193: 337-342. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.11.017 [40] PENG P, HUANG H, REN H. Effect of adding low-concentration of rhamnolipid on reactor performances and microbial community evolution in MBBRs for low C/N ratio and antibiotic wastewater treatment[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2018, 256: 557-561. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.02.035 [41] VAN N L, JETTEN M S M. Anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria: Unique microorganisms with exceptional properties[J]. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 2012, 76(3): 585-596. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05025-11 [42] WANG Q, HE J. Complete nitrogen removal via simultaneous nitrification and denitrification by a novel phosphate accumulating Thauera sp. strain SND5[J]. Water Research, 2020, 185: 116300. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116300 [43] 毛跃建. 废水处理系统中重要功能类群Thauera属种群结构与功能的研究[D]. 上海: 上海交通大学, 2009. [44] CHEN H J, ZHOU W Z, ZHU S N, et al. Biological nitrogen and phosphorus removal by a phosphorus-accumulating bacteria Acinetobacter sp. strain C-13 with the ability of heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2020, 322: 124507. [45] LIU S, LI J. Accumulation and isolation of simultaneous denitrifying polyphosphate-accumulating organisms in an improved sequencing batch reactor system at low temperature[J]. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 2015, 100: 140-148. [46] 杨垒, 陈宁, 任勇翔, 等. 异养硝化细菌Acinetobacter junii NP1的同步脱氮除磷特性及动力学分析[J]. 环境科学, 2019, 40(8): 3713-3721. [47] WAN W, HE D, XUE Z. Removal of nitrogen and phosphorus by heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification of a denitrifying phosphorus-accumulating bacterium Enterobacter cloacae HW-15[J]. Ecological Engineering, 2017, 99: 199-208. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.11.030 [48] 余俊霞, 陈双荣, 刘凌言, 等. 复合人工湿地系统对低污染水总氮的净化效果及其微生物群落结构特征[J/OL]. 环境工程: 1-11[2021-10-03]. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.2097.X.20210617.1622.018.html. [49] 李维, 石先阳. 氧化锌纳米颗粒对SBR中活性污泥脱氮性能及硝化细菌丰度的影响[J]. 环境工程学报, 2017, 11(8): 4549-4558. doi: 10.12030/j.cjee.201606123 [50] 王涛, 张栋, 戴翎翎, 等. 纳米材料对污水/污泥厌氧消化系统影响的研究进展[J]. 环境工程, 2015, 33(6): 1-5. [51] 魏佳明, 崔丽娟, 李伟, 等. 表流湿地细菌群落结构特征[J]. 环境科学, 2016, 37(11): 4357-4365. -

DownLoad:

DownLoad: