-

安全清洁的饮用水与人群健康息息相关,也是我国当前经济社会发展中的重大民生问题之一[1]。饮用水处理工艺经过百余年的发展,特别是消毒工艺的应用,为消除伤寒、霍乱等介水传播疾病做出了重大贡献。但随着检测技术的不断发展,耐氯性条件致病菌在饮用水系统中被不断检出[2-3]。有研究[4]显示,人类仍有50%的疾病与饮用水中病原微生物有关。因此,探究饮用水处理工艺中细菌群落的时空分布与动态变化,对病原微生物控制技术的开发,进而保障人群健康具有重要意义。

高通量测序因其准确性高、成本低等优点,在供水系统微生物群落解析中应用广泛。目前,已有利用该技术对常规处理工艺[5]、臭氧-生物活性炭深度处理工艺[6]、炭砂滤池处理工艺[7]等工艺过程中细菌群落多样性进行解析的很多案例。但是,针对超滤工艺及其组合净水工艺过程中细菌群落变化的研究却鲜见报道[8]。

本研究以我国南方某基于活性炭-超滤深度处理工艺的自来水厂为采样地,采用NovaSeq6000高通量测序技术对夏季和冬季各工艺单元出水和活性炭生物膜的细菌群落进行解析,以探究细菌群落在工艺过程中的分布与变化规律;并了解主要条件致病菌属的组成,以期为全面保障饮用水安全提供参考。

全文HTML

-

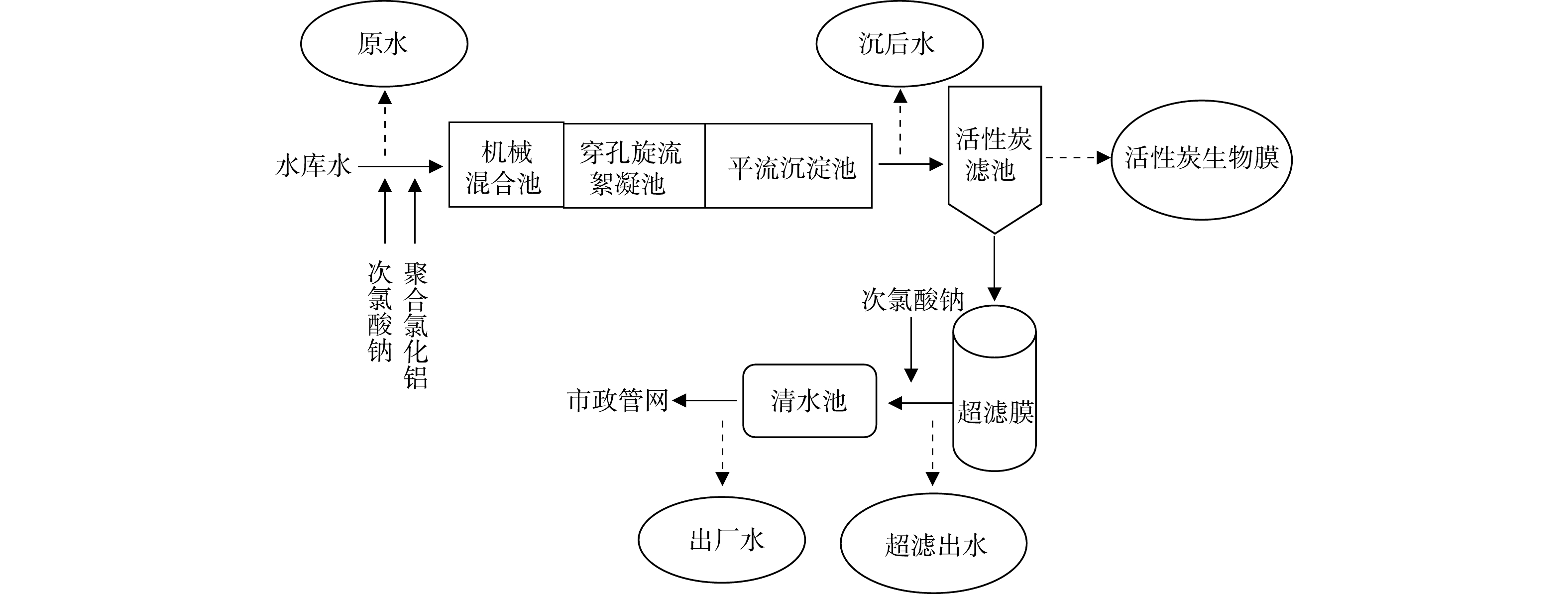

该自来水厂(以下简称“水厂”)设计规模为40 000 t·d−1,供水面积约4 km2,服务人口约160 000人。水源水来自水库。以机械混合池、穿孔旋流絮凝池、斜管沉淀池、活性炭滤池、超滤膜车间和清水池为主要工艺单元,工艺流程如图1所示。混凝剂选用聚合氯化铝,投加量为1.0~2.0 mg·L−1(以氧化铝计);预氧化剂和消毒剂均采用次氯酸钠,预氧化投加量为0.5~1.0 mg·L−1,主消毒投加量为1.5~2.0 mg·L−1,均以Cl2计。

-

水样来自GAC-UF各工艺单元的出水,生物膜样品则采集自GAC-UF活性炭滤池中的活性炭,样品采集时各工艺单元设备运行状态良好。采样点如图1所示。样品名称分别为原水、沉后水、炭滤出水、超滤出水、出厂水和活性炭生物膜,对应的夏季(7月份)样品编号为S.RW、S.CSE、S.GACFE、S.UFE、S.FW和S.GACB;对应的冬季样品编号为W.RW、W.CSE、W.GACFE、W.UFE、W.FW和W.GACB。水样采集所用塑料桶须进行灭菌处理,活性炭样品置于无菌袋中。以上样品均需要采集3份平行样品,混合均匀后方可进行样品检测[9]。水样及活性炭样品要及时进行检测,如无条件立即进行检测,需于4 ℃条件下保存,并在24 h内完成检测。活性炭样品的处理步骤参考文献[10]。采用0.22 μm滤膜对水样和活性炭样品的处理上清液进行过滤,直到滤膜无法下滤为止。之后将滤膜置于灭菌处理的离心管中,于−80 ℃条件下保存。

-

使用HACH HQd多参数水质分析仪对刚采集样品的pH、水温和溶解氧立即进行测定;使用HACH 2100AN浊度分析仪、GE Sievers 5310C总有机碳测定仪、VARIAN CARY50型号紫外-可见分光光度计对浊度、TOC/DOC、UV254进行检测;使用《生活饮用水标准检验方法》(GB/T 5750-2006)[11]的方法对总磷、氨氮、高锰酸盐指数(CODMn)、菌落总数等指标进行检测;生物可降解溶解性有机碳(BDOC)测定方法参考文献[12];异养菌平板计数(HPC)参考文献[13]。

-

首先,各样品的基因组DNA使用十六烷基三甲基溴化铵(CTAB)法提取,采用无菌水将提取获得的DNA稀释至1 ng·μL−1,以此DNA为模板,选择515F和806R等16S V4区引物进行聚合酶链式反应(PCR)。然后,采用琼脂糖凝胶(浓度为2%)对PCR产物进行电泳检测,并用胶回收试剂盒(qiagen公司)对目的条带进行回收。最后,利用TruSeq® DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit建库试剂盒构建文库,通过Qubit和Q-PCR对文库进行定量,文库确认合格后,在NovaSeq6000平台上进行测序。

-

在97%一致性水平上,将测序获得的有效数据采用Uparse软件聚类为OTUs(operational taxonomic units)。之后对OTUs通过Mothur方法与SILVA的SSUrRNA数据库注释分析其所代表的物种,并在门、纲、属水平上进行样品的群落组成分析。同时,将数据均一化,以分析细菌群落多样性。

α多样性指数和PCA分析分别采用Qiime软件(Version 1.7.0)和R软件(Version 2.15.3)完成。

1.1. 水厂概况及处理工艺

1.2. 样品处理、采集与保存

1.3. 水质指标的测定

1.4. 细菌群落测序分析

1.5. 测序数据分析

-

表1为GAC-UF深度处理工艺过程的水质参数变化。通过分析表1可知,出厂水pH、浊度、CODMn、菌落总数等指标均能满足《生活饮用水卫生标准》(GB 5749-2006)[14]的要求。现行的美国饮用水水质标准中,对HPC的限值是500 CFU·mL−1[15],本研究中两个季节的数据均没有超标;但是,冬季出厂水的HPC已达323 CFU·mL−1。HPC作为微生物学指标,需要引起重视。此外,冬季各工艺单元HPC远高于菌落总数。由于与测定菌落总数的营养琼脂培养基相比,测定HPC的R2A培养基有机物组成更加广泛,更有利于受损细菌的修复生长,因此,冬季更应强化工艺运行,以保障饮用水微生物安全。

除pH、水温和溶解氧3项指标以外,工艺过程中的其他指标基本呈现下降趋势。其中,夏季和冬季对浊度、氨氮、BDOC、菌落总数的去除率基本相同,且与相关研究结果基本吻合[16]。

-

夏季和冬季的水样、生物膜样品α多样性指数如表2所示。由表2可知,Good’s coverage均在0.98以上。由此可以看出,对于水样、活性炭生物膜样品中细菌群落的覆盖率,16S rRNA测序均能达到较高。

在水样方面,除在GAC工艺单元有大幅升高外,OTUs和Shannon、Chao1等α多样性指数在活性炭-超滤深度处理工艺过程中整体呈下降趋势,混凝沉淀工艺单元、UF工艺单元和消毒工艺单元对细菌多样性均起到削减作用。此外,夏季对OTUs、Shannon和Chao1的去除率(48.02%、39.68%、53.84%)明显高于冬季(42.57%、21.07%、36.05%)。其主要原因可能是,冬季水温较夏季低10 ℃左右,较低的温度影响了工艺运行效果。以上结果均表现了GAC-UF深度处理工艺中细菌群落明显的时空变化特性。此外,冬季水样和生物膜样品OTUs数目和α多样性指数均高于夏季。HOU等[7]对广州某炭砂滤池处理工艺水厂的研究结果与本文的结果一致;但任红星[17]对我国东部某臭氧-生物活性炭深度处理工艺的研究结果却与本文结果相反。以上内容表明,在不同地域水厂工艺过程中,细菌群落多样性的时间变化特性有所差异,产生这一结果可能与原水(水源水)中的营养物质组成有关[18]。

细菌群落多样性在GAC-UF深度处理工艺过程中整体呈下降趋势,但在GAC单元出水中明显升高,且活性炭生物膜细菌群落多样性亦高于原水。以上结果均表明,GAC滤池中细菌的大量孳生。BOON等[19]的研究也表明GAC滤池出水中大量微生物的存在。混凝沉淀工艺单元、UF工艺单元和消毒工艺单元均对细菌群落多样性起到削减作用,混凝沉淀工艺单元对细菌群落多样性的去除率在20%左右。但是,POITELON等[20]和LIN等[5]的研究结果表明,混凝沉淀工艺单元对细菌群落的影响作用较小,这与本文结果有一定出入。其可能的原因是,本研究中添加了次氯酸钠作为预氧化剂,强化了混凝沉淀工艺对细菌群落的去除。在UF工艺单元,2个季节对细菌多样性的去除作用均较为明显,表明了超滤膜对微生物的有效截留,这与乔铁军等[21]的研究结果一致。消毒工艺单元是保障饮用水微生物安全最主要的屏障,其在夏季对细菌群落多样性的去除率最高,但在冬季去除率较低,这可能与耐氯菌的存在有关。

-

1)门水平上的细菌群落组成。门水平上的细菌群落组成如图2所示。由图2可知,2个季节水样的主要菌门组成基本相同;不同的是,变形菌门(Proteobacteria)在夏季样品中占绝对优势,而放线菌门(Actinobacteria)在冬季各水样中相对丰度略高于变形菌门(Proteobacteria)。相较各水样而言,在活性炭生物膜样品(S.GACB和W.GACB)中,变形菌门(Proteobacteria)在夏季(60.79%)和冬季(72.15%)均占绝对优势;夏季主要菌门还包括浮霉菌门(Planctomycetes,12.79%)、酸杆菌门(Acidobacteria,5.06%)和奇古菌门(Thaumarchaeota,3.62%),冬季还包括软壁菌门(Tenericutes,4.83%)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria,4.04%)和浮霉菌门(Planctomycetes,3.12%)。

综上所述,水样和生物膜样品细菌群落组成在门水平上存在一定差异,且生物膜样品差异更为明显;但综合这两种样品来看,占有绝对优势的菌门仍为变形菌门(Proteobacteria)。

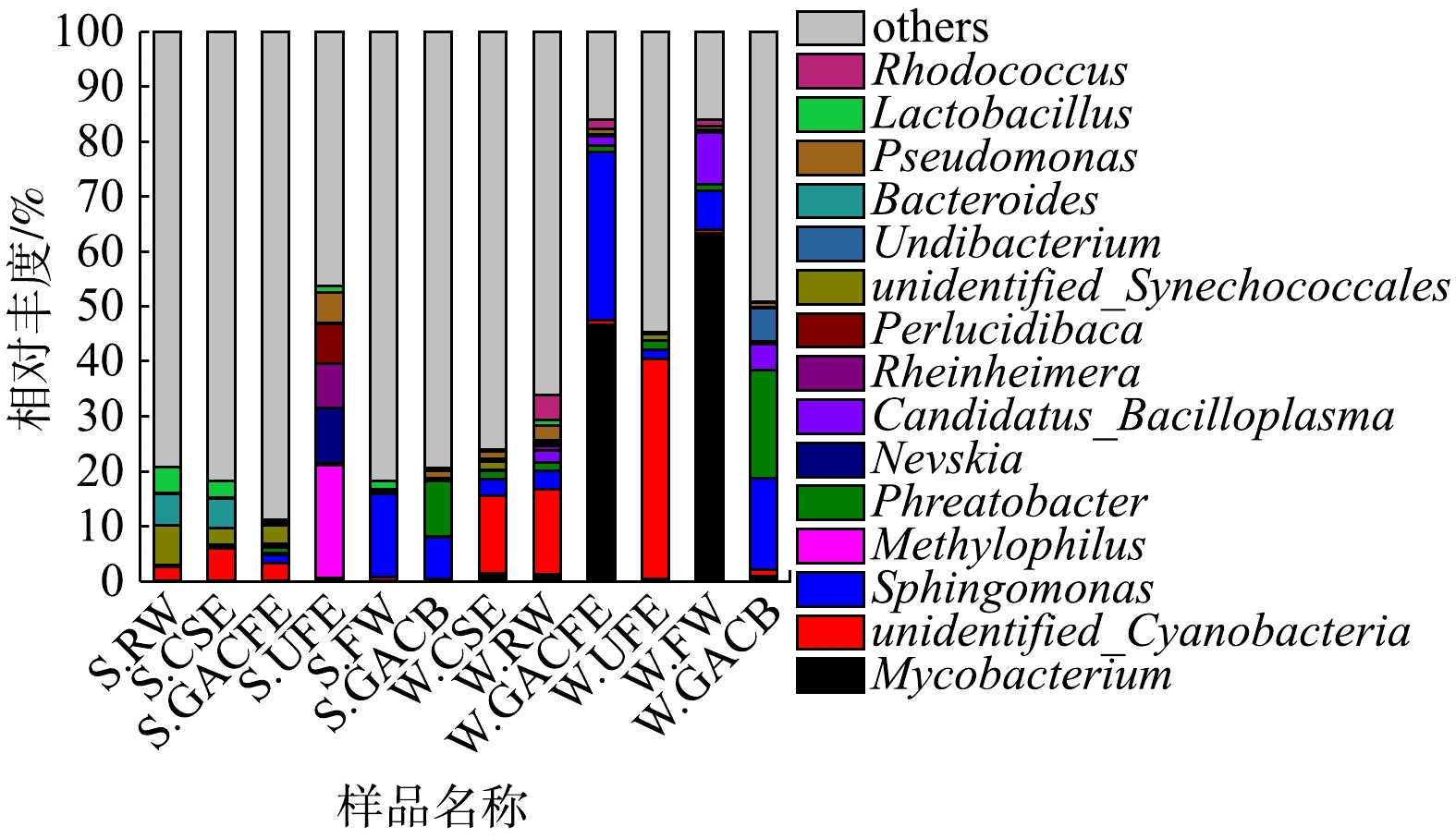

2)属水平上的细菌群落组成。夏、冬两季在属水平上的细菌群落组成如图3所示。由图3可知,在属水平组成上,2个季节的细菌群落组成差异性更为明显,如在S.FW中绝对优势菌属为鞘氨醇单胞菌属(Sphingomonas,15.15%),在W.FW中绝对优势菌属为分支杆菌属(Mycobacterium,63.32%)。根据祝泽兵[3]的研究,这2种菌属均具有一定的耐氯性。此外,可能正是由于大量分支杆菌属(Mycobacterium)等耐氯菌的存在,造成了冬季消毒工艺对细菌多样性的去除率较低。

根据相关研究[22]报道,分支杆菌属(Mycobacterium)和假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas)为条件致病菌属。这2种条件致病菌属在冬季样品中的相对丰度高于夏季,且分支杆菌属(Mycobacterium)在活性炭池中更易孳生,出水丰度较沉淀池出水有所增加,特别是冬季样品增加较多。此外,在常规处理工艺[5]、臭氧-生物活性炭深度处理工艺[6]、炭砂滤池处理工艺[7]中亦发现不动杆菌属(Acinetobacter)、梭菌属(Clostridium)、军团菌属(Legionella)、气单胞菌属(Aeromonas)、沙门菌属(Salmonella)、链球菌属(Streptococcus)等多种条件致病菌属,且在供水管网系统中也有检出[23]。虽然大多数条件致病菌属相对丰度均较低,但其也包含非致病菌种[24],这仍需引起关注,后续应加强致病菌种水平和更有效灭活方式的研究。

-

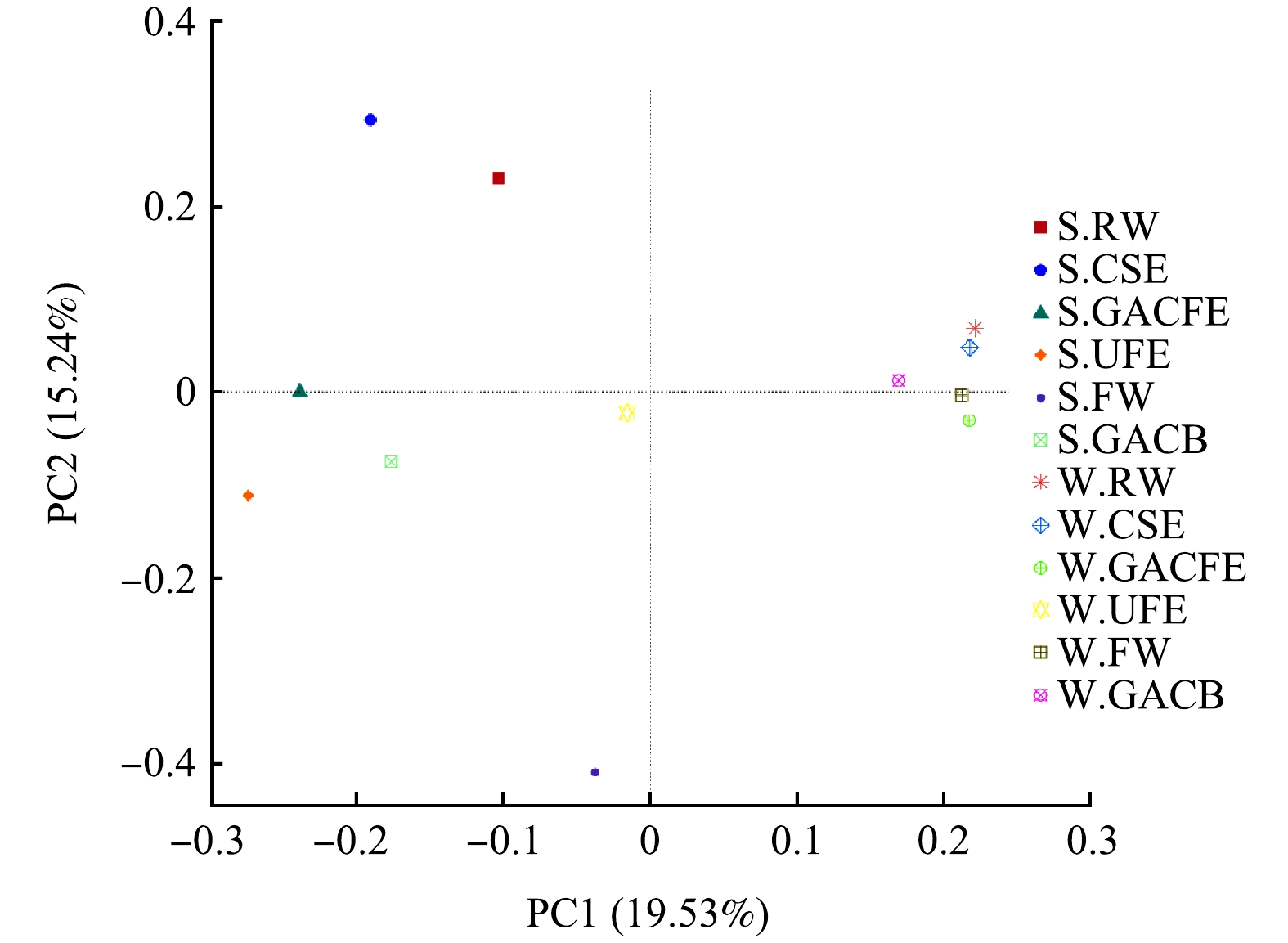

采用主成分分析对细菌群落的组成变化进行了研究,结果如图4所示。由图4可知,除冬季超滤出水(W.UFE)外,夏、冬两季样品分别分布在第一主成分(横坐标)两侧,这表明细菌群落组成的季节性变化非常明显。冬季超滤出水(W.UFE)远离所有样品,这说明其与其他样品细菌群落组成差异较大。与冬季相比,夏季各样品之间距离均较远,这说明各工艺单元之间的细菌群落组成差异亦更大。

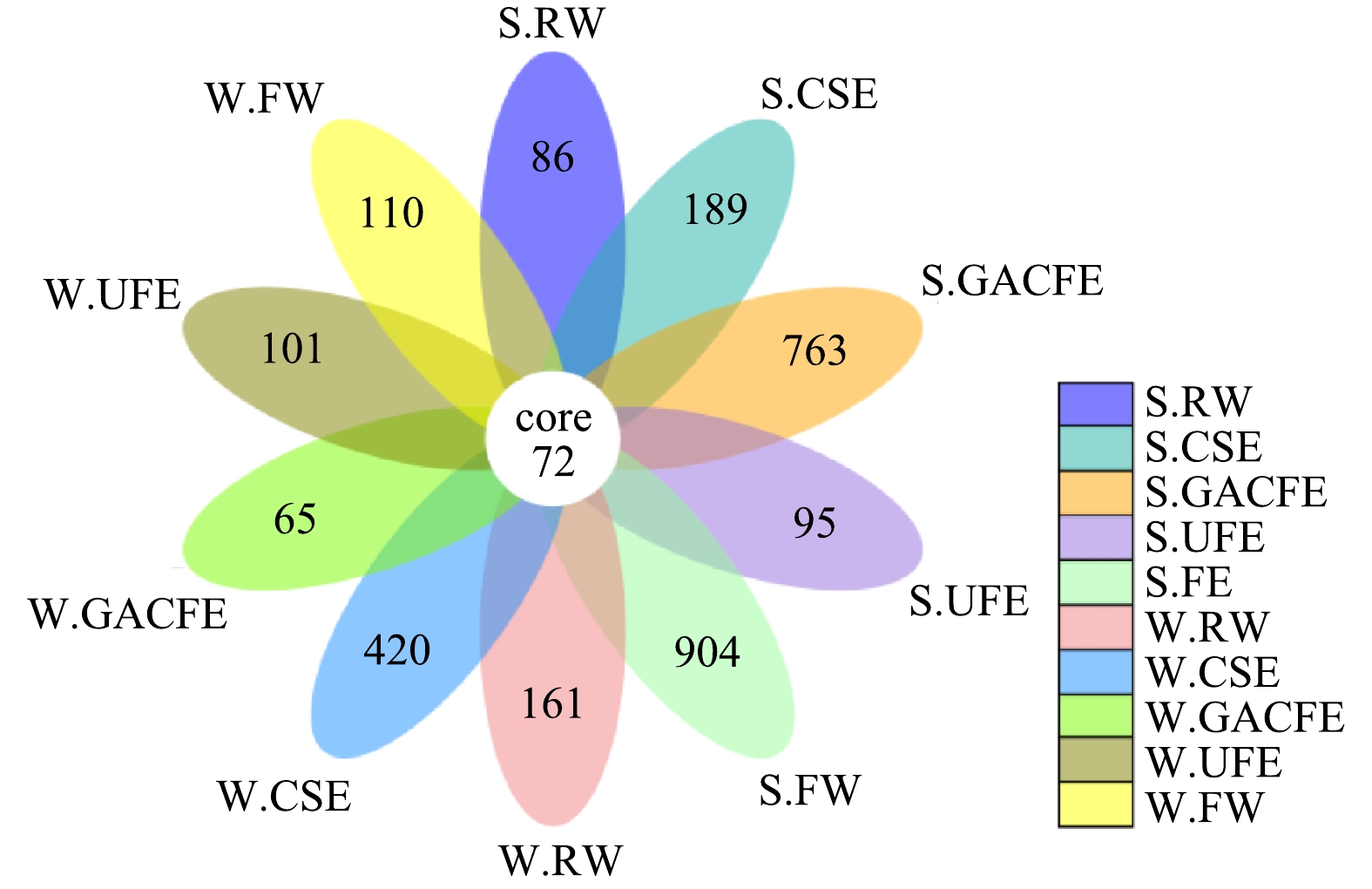

为明确工艺过程中的核心微生物,对夏、冬两季工艺水样共有和特有OTUs进行花瓣图分析,结果如图5所示。由图5可知,所有水样共有的OTUs数目是72,这说明一部分细菌不仅稳定存在于水样中,不受季节的影响;而且最终可能会进入龙头水,对人群健康造成危害。在核心微生物72个OTUs中,条件致病菌属分支杆菌属(Mycobacterium)和假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas)所占数目为1和3,所占比例合计为5.56%。

2.1. GAC-UF深度处理工艺运行效果

2.2. 工艺过程中细菌群落多样性变化

2.3. 工艺过程中细菌群落组成

2.4. 细菌群落组成变化及核心微生物

-

1)出厂水中浊度、菌落总数等水质指标均符合国标GB 5749-2006的要求。

2)细菌群落多样性在工艺过程中呈明显的时空分布变化,混凝沉淀、UF和消毒是去除细菌群落多样性的主要工艺单元,且夏季去除率明显高于冬季。

3)主要菌门组成为变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria)等;在属水平上细菌群落组成差异较大。

4)条件致病菌属主要包括分支杆菌属(Mycobacterium)和假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas),其在核心微生物中合计占比为5.56%。

下载:

下载: