-

多环芳烃(polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,PAHs)是一类具有代表性的持久性有机污染物(persistent organic pollutants,POPs)[1],主要由化石燃料或生物质的不完全燃烧产生;其来源分为自然源(森林火灾和火山喷发)和人为源(垃圾焚烧、道路扬尘、石油精炼、交通运输等),其中人为源排放是导致PAHs含量剧增的主要原因[2]. 相较于其它有机污染物,PAHs具有种类多、浓度高、分布广、毒性作用显著等特点. 由于具有致癌、致畸、致突变的“三致”毒性[3],USEPA在1979年规定16种PAHs为优先控制污染物[4].

多环芳烃及其衍生物对人体的暴露途径主要包括吸入、摄入和皮肤接触. PAHs污染物作为外源性化学物质在进入人体后,首先被血液吸收,然后通过血液系统进行分布,将PAHs运输到靶器官[5]. 研究证明,多环芳烃可诱发多种疾病,如白内障、肾和肝损伤以及黄疸、肺癌、皮肤癌、膀胱癌等[6]. 近年来,PAHs衍生物也被发现具有致毒致癌效应[7],如含氧多环芳烃(oxygenated-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,OPAHs)引发人体过敏性疾病和细胞凋亡[7]. 目前为止,关于人体PAHs、OPAHs的暴露水平的研究大多集中在外暴露中,依据环境中检测到的污染物浓度水平,运用模型公式和评估参数计算个体的污染物摄入量. 由于这些数据存在时间和空间上的差距,在人体暴露评估中可能存在局限性,不能反映出真实的暴露水平. 相比之下,内暴露通过检测人体体液或组织液的污染物浓度,其暴露水平更具有准确性、真实性. 通过研究人体内多环芳烃类污染物的暴露特征,有助于评估这些物质对人体的身体负担和潜在的毒性作用.

本研究选择天津市45名青年男性为研究对象,进行血浆样本的采集,对血浆中的PAHs、OPAHs的浓度水平及化学组成进行分析,并结合特征比值法和主成分分析方法解析目标物的来源,运用苯并[a]芘毒性当量(BaPeq)和致癌风险模型评估健康风险.

-

本项研究共采集了天津45名青年男性的血液,参与人员的年龄在25—35岁之间,均在市区居住;无不良生活习惯,工作内容相似且无职业暴露风险. 将采集的静脉血置于含抗凝剂的2 mL EDTA采血管中,以3000 r·min−1离心10 min,取血浆于冻存管,并转移至-20 ℃冰箱中保存直至分析. 所有参与者都被详细告知研究目的,均签订知情同意书. 本研究符合卫生部人类医学伦理审查法和赫尔辛基宣言.

-

将500 µL血浆转移至10 mL聚丙烯离心管中,加入1 mL醋酸铵溶液(1 mol·L−1)、0.25 mL甲酸溶液(1 mol·L−1)和1.2 mL超纯水使蛋白质变性. 超声处理10 min后,以4000 r·min−1离心5 min. 提取物的净化使用SPE柱进行,依次用5 mL正己烷、5 mL二氯甲烷、5 mL丙酮、5 mL甲醇和5 mL超纯水预先活化. 样品中加入40 µL替代标准品(Phe-D10、Chr-D12),经SPE柱提取后, 9 mL正己烷:二氯甲烷(V:V=1:1)混合溶剂进行目标物质的的洗脱. 安瓿瓶收集洗脱液,在温和的氮气流下吹至近干;然后使用500 µL正己烷进行复溶,样品移至进样瓶.

-

本研究选用岛津气相色谱-质谱联用仪(GC-MS)对多种PAHs及OPAHs进行定性和定量测定.

色谱参数设置:色谱柱型号为DB-5MS毛细管柱((SHIMADZU;30 m × 0.25 mm,0.25 μm),升温程序如下:初始温度为65 ℃,保持0.5 min;以15 ℃·min−1的升温速率升至130 ℃,保持0.5 min;再以9 ℃·min−1的速率升至220 ℃,保持1 min;然后以7 ℃·min−1的速率升至240 ℃,保持1.5 min;最后以15 ℃·min−1升温至320 ℃,保持5 min,升温程序的总时长为31.02 min. 进样口温度为270 ℃;进样量为5 µL. 采用脉冲不分流方式进样,载气为氦气,流速为1.4 mL·min−1.

质谱参数设置:质谱仪配置电子轰击电离源(EI),电离电压为70 eV;离子源温度230 ℃;传输线温度为270 ℃;溶剂延迟时间5 min;本研究采用选择离子监测模式(SIM)对目标组分进行检测,具体参数见表1.

-

为确保PAHs及其衍生物测定的准确性,样本分析前测定正己烷溶液检测仪器本底值,直至仪器本底值低于检出限后进行样品测定. 每5个样品中插入正己烷空白,空白样品中均未检测到目标物. 在样品中加入替代标准品,所有血样和空白的两种替代标准的平均回收率在87.6%—150.2%之间,基质加标的相对标准偏差(RSD)小于10%. 目标化合物的检出限(LOD)定义为3倍信噪比,方法检出限范围为0.40—1.80 ng·mL−1.

-

采用SPSS 22.0统计软件进行基础数据的处理和主成分分析、Origin 8.0软件进行数据分析和绘图.

-

本研究通过对血浆样品中PAHs及OPAHs进行分析,共检测到7种PAHs、检出率范围为17.8%—80.0%(如表2所示),与Yang等报道的PAHs检出率范围相似[8]. 在7种单体PAHs中,Phe的检出率最高(80.0%),其次是DBahA(66.7%),Koukoulakis等对希腊成年人血清的研究中也表明了Phe具有较高的检出率[9]. 其他单体PAHs检出率均低于50%,其中BghiP的检出率最低(17.8%).

ΣPAHs的浓度范围为10.1—111.2 ng·mL−1,平均值为24.8 ng·mL−1 (表2). 在检测到的单体PAHs中,DBahA、Phe具有较高的浓度(分别为14.2 ng·mL−1、10.8 ng·mL−1),也是其中检出率最高的2个单体PAHs,浓度最低的是BghiP(1.4 ng·mL−1). Koukoulakis等在血清中的研究发现Phe等7种PAHs的浓度范围为1.95—62.2 ng·mL−1(病例组)和1.26—48.6 ng·mL−1(控制组)[9];Singh等[10]对印度儿童血清PAHs检测的结果显示Phe、Ant、Flu、Pyr浓度分别为9.0 ng·mL−1、3.6 ng·mL−1、6.0 ng·mL−1和9.0 ng·mL−1. 本研究中的PAHs浓度范围上述两项研究中浓度范围基本一致.

在血浆样品中OPAHs的检出率为95.6%,其中Phe-9-Ald、BZO、NCQ、7,12-BaAOs的检出率较高(均大于60%),而Dibf的检出率最低(28.9%). Σ6OPAHs的浓度范围为Nd—85.5 ng·mL−1,平均值为31.9 ng·mL−1,在检测到的单体中,ATO具有最高的浓度(27.1 ng·mL−1),浓度最低的是BZO(4.3 ng·mL−1). 目前,国内外关于OPAHs的研究报道主要集中在环境介质中,动物、人体中OPAHs的研究报道较少,尚不能提供数据上的参照.

-

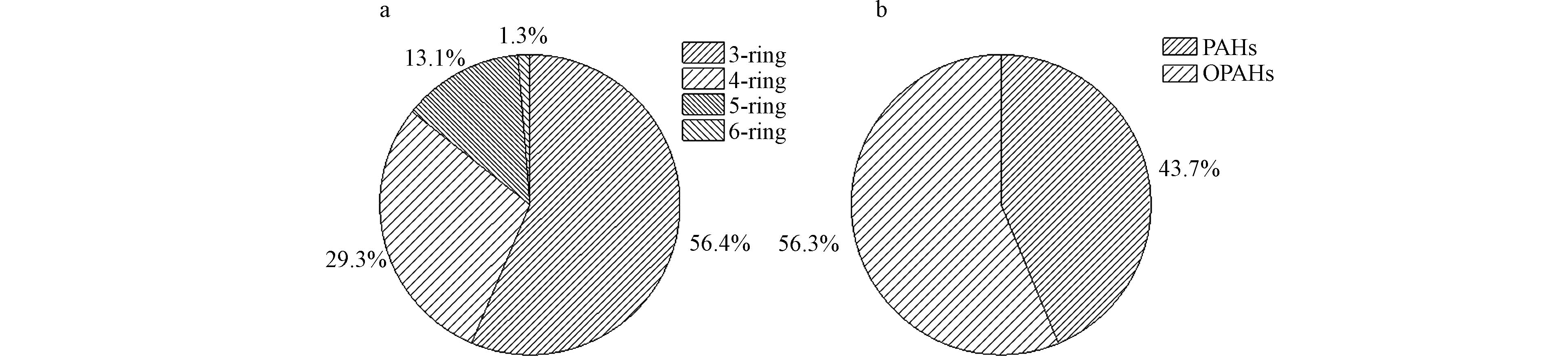

血浆PAHs和OPAHs的分子组成从3环到6环均有分布,其中3环为Phe、Flo、Ant和ATO、Phe-9-Ald,占总量的56%,4环为Flu、Pyr和BZO、NCQ、7,12-BaAO,占总量的29%,5环和6环分别为DBahA和BghiP,分别占13.1%和1.3%(图1a). 血浆中检测到的PAHs和OPAHs成分主要以低-中分子量物质为主,Yin等在脐带血清的研究中发现了低分子量多环芳烃的比例高于高分子量多环芳烃[11],来自印度不同地区的多环芳烃监测研究也报告了儿童血清中低-中分子量多环芳烃多于高分子量多环芳烃[10],低-中-高分子量多环芳烃在人体中的分布呈现一致性. 该分布状况的形成与高分子量物质易与大颗粒物结合富集在地面,低中分子量物质易与较小的颗粒物结合悬浮在空气中有关,通过呼吸进入人体的低中环分子量物质较多,是导致血浆中PAHs和OPAHs以低中分子含量为主的重要因素之一.

在血浆样品中检测到的OPAHs浓度高于PAHs,分别占比56%和44%(图1b). 由于目前在人体内暴露中检测OPAHs的研究有限,目前在一些环境介质中的研究中,发现PAHs衍生物低于PAHs浓度;Bandowe等的研究报告称,乌兹别克斯坦一处工业区的土壤中多环芳烃衍生物(MPAHs,OPAH)的含量低于PAHs的含量[12];Wang等在北京大气颗粒中的研究中发现OPAHs的浓度低于PAHs[13],在环境中的调查与本研究结果不同. 据报道,多环芳烃衍生物与其母体PAHs相似,可以直接从岩源或热源中产生[14],此外,PAHs衍生物还可以通过PAHs在人体内的代谢而逐渐生成[15],这种转化可能是OPAHs的浓度高于PAHs的原因. 人体中出现OPAHs浓度较高的情况应引起重视,在有限的研究中表明OPAHs的毒性可能与PAHs的毒性相同甚至更高. OPAHs在细胞水平上的毒性作用能显著降低人脐静脉内皮细胞(HUVECs)一氧化氮(NO)的生成,存在潜在的内皮损伤效应,可成为人类细胞高致突变的诱变剂[16].

-

由于不同的排放源会产生特定的多环芳烃标志物,PAHs特征比值法常被用来判别多环芳烃类污染物的可能来源. 本研究选用以往研究中广泛使用的4种特征值应用于本研究血清中PAHs的来源解析[9, 17-18]. 各类成因对应污染源中PAHs特征比值如表3所示,在本研究中通过特征值的分析,表明石油源和化石燃料的不完全燃烧是PAHs产生的的重要来源.

-

为进一步研究PAHs的来源情况,采用主成分分析法定量分析血浆中PAHs类物质的来源,提取初始特征值大于1的因子,2个主因子的累计方差贡献率为79.7%,7种PAHs主成分因子载荷如表4所示.

一般认为低分子量的PAHs主要来源于石油的泄漏、化石燃料和生物质的不完全燃烧,而高温燃烧过程主要形成高分子量的PAHs;如在PAHs的来源分析中Pyr、Phe等低中分子量主要与煤燃烧有关,DBahA、BghiP是汽车排放的重要化合物[19-21]. 主因子1具有最高的方差贡献率(70.2%),在主因子1的单体PAHs中只有DBahA具有很高的载荷,表明PAHs的来源是交通燃油排放;主因子2的方差贡献率为9.5%,在单体PAHs中Phe具有最高载荷,其次是Pyr、Flu等低分子量PAHs也具有较高载荷,表明燃煤是主因子2的主要来源. 本研究通过主成分分析表明交通燃油排放是主要污染源,而燃煤来源为PAHs的第二污染源. 其分析结果与特征比值法的结果相互吻合. 综上所述石油源和化石燃料的燃烧是PAHs产生的重要来源,通过对PAHs来源的解析有助于更好地了解排放途径和不同来源的贡献,为未来的风险管理提供科学依据.

有关OPAHs来源途径较多,即可来自于一次排放,也可来自于二次生成. 目前关于OPAHs的具体来源途径尚未有明确的判别方法,可供参考的研究资料有限,尚需进行进一步的研究工作,以期揭示OPAHs具体来源途径及其影响因素.

-

依据药代动力学模型从血浆中多环芳烃含量推算每日总摄入量(TEDIs)如公式(1)所示,当血浆中的多环芳烃的浓度不在随时间变化时,即

dc/dt =0,即血浆的多环芳烃浓度达到平衡,可以以此计算出每日总摄入量[8]. 由于目前的在药代动力学的模型中只有Pyr的参数齐全,本研究中只选取Pyr作为讨论对象.式中,C为血浆中单体多环芳烃的浓度;V为人体的血量(L),一般认为是男性血量为体重的8%;BW为体重(kg);A(无量纲)为Pyr摄入剂量的吸收速率为0.90;f(无量纲)是Pyr吸收剂量分布在血液中的比例为0.052;b代表Pyr的消除速率常数为0.068;式中这些参数参考Haddad[22]和Viau[23]的研究结果.

以血浆中Pyr浓度为基础,基于公式(1)计算血浆中Pyr的每日总摄入量. 其TEDI的范围为0.296—2.928 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw,平均浓度为0.935 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw,见表5.

由于每种单体PAHs具有不同程度的毒性,国内外的研究中通常采用苯并[a]芘当量浓度(BaP equivalent, BaPeq)来评估得到其他单体PAHs的毒性,各单体PAHs的BaPeq毒性当量计算公式如(2)所示。

式中,BaPeqi为各PAHs单体的BaP当量毒性,TEFi为对应PAHs单体的毒性当量因子(Pyr的毒性当量因子为0.001).

-

(1)非致癌系数(HQ)是每日摄入量(TEDI)与美国环保局提供每日参考剂量(RfD)的比值,若HQ>1,则说明存在非致癌风险;HQ<1,则表明不存在致癌风险[24]. Pyr的参考剂量为30 μg·kg−1-bw·d−1,计算公式如(3)所示.

(2)PAHs暴露的致癌风险的计算,如公式(4)所示。

式中,CSF为致癌斜率因子,本研究选用BaP的口服致癌斜率因子[8][7.3 (kg·d)·mg−1]. 根据美国环保署规定,CR<10−6时,引发的致癌风险不明显;CR在10−4和10−6之间时,表明具有潜在的致癌风险;CR>10−4时,表明存在很高的致癌风险[25].

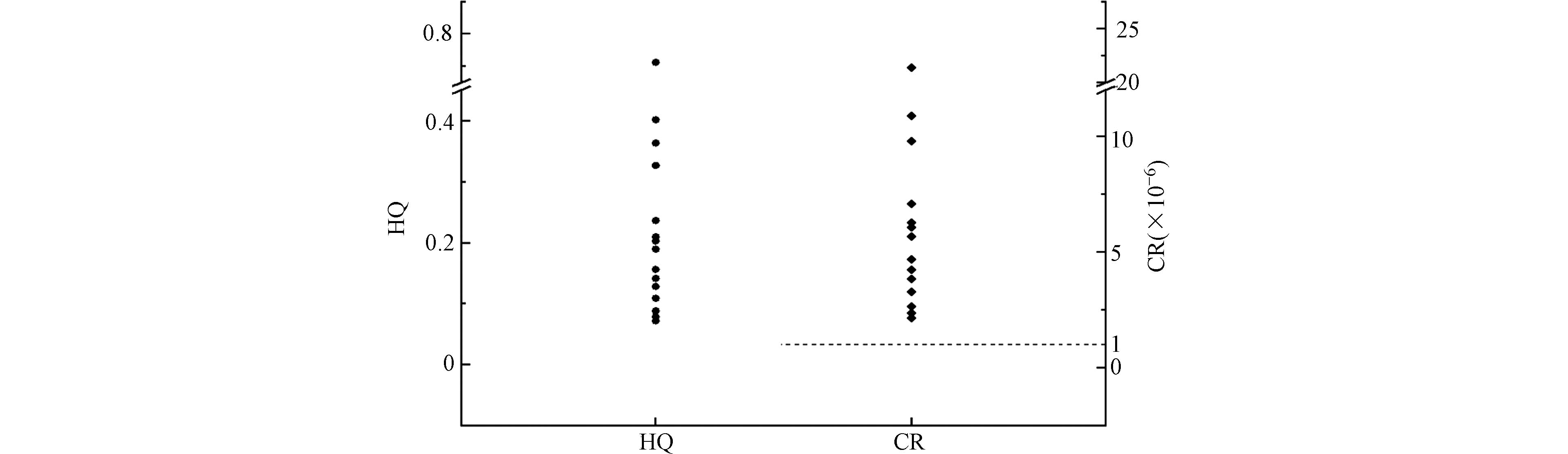

分别计算了HQ和CR值(图2),以评估血浆中Pyr内暴露的非致癌和致癌风险. 血浆中Pyr的HQ值范围为0.072—0.712,中位数为0.189,表明人体血浆中的多环芳烃不存在非致癌风险. 然而,当考虑致癌风险时,基于苯并[a]芘当量浓度的致癌风险应引起足够关注,血浆中CR值的范围为2.16×10−6—2.14×10−5,中位数为5.67×10−6,所用个体的CR值均超过了1×10−6,表明血浆中PAHs存在潜在的致癌风险.

-

在天津市45名青年人群血浆中共检测出7种PAHs和6种OPAHs,ΣPAHs和∑OPAHs平均浓度分别为24.8 ng·mL−1和31.9 ng·mL−1. 其单体化合物中ATO、DBahA的相对含量较高,对人群健康的潜在危害较大,应重点关注. 且PAHs和OPAHs组成特征以低中环物质为主,占总质量浓度的85%. 石油源和化石燃料的燃烧为人群血浆中PAHs的重要来源. 通过致癌风险评估,表明血浆中的PAHs存在潜在的致癌风险,后续应加大对人群内暴露的全面监测和长期健康风险的评估.

人体血浆中多环芳烃及含氧多环芳烃的暴露特征及健康风险评估

Exposure characteristics and health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and oxygenated derivatives in human plasma

-

摘要: 为探究人体多环芳烃(PAHs)及含氧多环芳烃(OPAHs)的内暴露水平、来源及健康效应,本研究采集了天津市45名青年男性的血浆样本,使用气相色谱-质谱法检测多环芳烃及含氧多环芳烃的暴露浓度,利用特征比值法和主成分分析法对其来源及贡献率进行解析,并利用苯并[a]芘(BaP)毒性当量浓度和致癌风险模型对致癌健康风险进行评估. 结果共检测出7种PAHs和6种OPAHs,检出率分别为17.8%—80.0%和28.9%—66.7%,ΣPAHs和∑OPAHs平均浓度为24.8 ng·mL−1和31.9 ng·mL−1;其中,二苯并(a, h)蒽(DBahA)和10H-9-蒽酮(ATO)的浓度水平最高(14.2 ng·mL−1、27.1 ng·mL−1),组成特征以低-中分子量物质为主. 使用特征比值法和主成分分析法进行污染来源分析,结果表明,石油源和化石燃料的燃烧是人体血浆中PAHs的重要来源. 通过致癌风险分析得出风险值(CR)介于10-4与10−6之间,表明血浆中的多环芳烃类物质存在潜在的致癌风险.Abstract: To investigate the internal exposure level, sources, and health effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and oxygenated-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (OPAHs) in human, the plasma samples of 45 young men were collected in Tianjin. The concentrations of PAHs and OPAHs in human plasma were measured using gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer instrument (GC-MS). The sources of the PAHs were analyzed by using diagnostics ratios and the principal component analysis (PCA), and the health risk of PAHs was assessed by BaP equivalent concentrations (BaPeq) and cancer risk (CR). Seven PAHs and six OPAHs were detected in the plasma samples. The detection frequencies of PAHs and OPAHs were in the range of 17.8%—80.0% and 28.9%—66.7%, respectively. The average concentration of ΣPAHs and ∑OPAHs were 24.8 ng·mL−1 and 31.9 ng·mL−1, DBahA, ATO were predominant species(14.2 ng·mL−1, 27.1 ng·mL−1, respectively), and the ring distribution of the PAHs was dominated by low–medium molecular weight components. The results of the diagnostics ratios and PCA suggested that PAHs originated mostly from petroleum source and petroleum combustion. Based on cancer risk analysis, CR values was between 10-4 and 10−6, indicating the potential carcinogenic risk of PAHs and their derivatives in plasma.

-

多环芳烃(polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,PAHs)是一类具有代表性的持久性有机污染物(persistent organic pollutants,POPs)[1],主要由化石燃料或生物质的不完全燃烧产生;其来源分为自然源(森林火灾和火山喷发)和人为源(垃圾焚烧、道路扬尘、石油精炼、交通运输等),其中人为源排放是导致PAHs含量剧增的主要原因[2]. 相较于其它有机污染物,PAHs具有种类多、浓度高、分布广、毒性作用显著等特点. 由于具有致癌、致畸、致突变的“三致”毒性[3],USEPA在1979年规定16种PAHs为优先控制污染物[4].

多环芳烃及其衍生物对人体的暴露途径主要包括吸入、摄入和皮肤接触. PAHs污染物作为外源性化学物质在进入人体后,首先被血液吸收,然后通过血液系统进行分布,将PAHs运输到靶器官[5]. 研究证明,多环芳烃可诱发多种疾病,如白内障、肾和肝损伤以及黄疸、肺癌、皮肤癌、膀胱癌等[6]. 近年来,PAHs衍生物也被发现具有致毒致癌效应[7],如含氧多环芳烃(oxygenated-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,OPAHs)引发人体过敏性疾病和细胞凋亡[7]. 目前为止,关于人体PAHs、OPAHs的暴露水平的研究大多集中在外暴露中,依据环境中检测到的污染物浓度水平,运用模型公式和评估参数计算个体的污染物摄入量. 由于这些数据存在时间和空间上的差距,在人体暴露评估中可能存在局限性,不能反映出真实的暴露水平. 相比之下,内暴露通过检测人体体液或组织液的污染物浓度,其暴露水平更具有准确性、真实性. 通过研究人体内多环芳烃类污染物的暴露特征,有助于评估这些物质对人体的身体负担和潜在的毒性作用.

本研究选择天津市45名青年男性为研究对象,进行血浆样本的采集,对血浆中的PAHs、OPAHs的浓度水平及化学组成进行分析,并结合特征比值法和主成分分析方法解析目标物的来源,运用苯并[a]芘毒性当量(BaPeq)和致癌风险模型评估健康风险.

1. 材料与方法(Materials and methods)

1.1 样品采集与储存

本项研究共采集了天津45名青年男性的血液,参与人员的年龄在25—35岁之间,均在市区居住;无不良生活习惯,工作内容相似且无职业暴露风险. 将采集的静脉血置于含抗凝剂的2 mL EDTA采血管中,以3000 r·min−1离心10 min,取血浆于冻存管,并转移至-20 ℃冰箱中保存直至分析. 所有参与者都被详细告知研究目的,均签订知情同意书. 本研究符合卫生部人类医学伦理审查法和赫尔辛基宣言.

1.2 血浆样品前处理

将500 µL血浆转移至10 mL聚丙烯离心管中,加入1 mL醋酸铵溶液(1 mol·L−1)、0.25 mL甲酸溶液(1 mol·L−1)和1.2 mL超纯水使蛋白质变性. 超声处理10 min后,以4000 r·min−1离心5 min. 提取物的净化使用SPE柱进行,依次用5 mL正己烷、5 mL二氯甲烷、5 mL丙酮、5 mL甲醇和5 mL超纯水预先活化. 样品中加入40 µL替代标准品(Phe-D10、Chr-D12),经SPE柱提取后, 9 mL正己烷:二氯甲烷(V:V=1:1)混合溶剂进行目标物质的的洗脱. 安瓿瓶收集洗脱液,在温和的氮气流下吹至近干;然后使用500 µL正己烷进行复溶,样品移至进样瓶.

1.3 仪器分析

本研究选用岛津气相色谱-质谱联用仪(GC-MS)对多种PAHs及OPAHs进行定性和定量测定.

色谱参数设置:色谱柱型号为DB-5MS毛细管柱((SHIMADZU;30 m × 0.25 mm,0.25 μm),升温程序如下:初始温度为65 ℃,保持0.5 min;以15 ℃·min−1的升温速率升至130 ℃,保持0.5 min;再以9 ℃·min−1的速率升至220 ℃,保持1 min;然后以7 ℃·min−1的速率升至240 ℃,保持1.5 min;最后以15 ℃·min−1升温至320 ℃,保持5 min,升温程序的总时长为31.02 min. 进样口温度为270 ℃;进样量为5 µL. 采用脉冲不分流方式进样,载气为氦气,流速为1.4 mL·min−1.

质谱参数设置:质谱仪配置电子轰击电离源(EI),电离电压为70 eV;离子源温度230 ℃;传输线温度为270 ℃;溶剂延迟时间5 min;本研究采用选择离子监测模式(SIM)对目标组分进行检测,具体参数见表1.

表 1 目标组分的检测离子Table 1. The monitoring ions of target components目标组分 Target component 定量离子 Quantifier ion (m/z) 定性离子 Qualifier ion (m/z) 芴 Fluorene(Flo) 166 165.00—164.00 菲 Phenanthrene(Phe) 178 176.00—152.00 蒽 Anthracene(Ant) 178 176.00—179.00 荧蒽 Fluoranthene(Flu) 202 200.00—203.00 芘 Pyrene(Pyr) 202 200.00—201.00 二苯并(a,h)蒽 Dibenz[a,h]anthracene(DBahA) 278 276.00—279.00 苯并(g,h,i)芘 Benzo[ghi]perylene(BghiP) 276 274.00—138.00 氧芴 Dibenzofuran(Dibf) 168 139.00—169.00 10H-9-蒽酮 10H-9-Anthracenone(ATQ) 208 152.00—180.00 菲-9-醛 Phenanthrene-9-carboxaldehyde(Phe-9-Ald) 178 206.00—176.00 苯并蒽酮 7H-Benz[de]anthracen-7-one(BZO) 230 202.00—200.00 5,12-四并苯醌 5,12-Naphthacenedione(NCQ) 258 202.00—230.00 苯并[a]蒽-7,12-二酮 Benz(a)anthracene-7,12-dione(7,12-BaAO) 258 202.00—230.00 菲-D10 Phenanthrene-D10(Phe-D10) 188 184.00—160.00 䓛-D12 Chrysene-D12(Chr-D12) 240 236.00—241.00 1.4 质量控制与质量保证

为确保PAHs及其衍生物测定的准确性,样本分析前测定正己烷溶液检测仪器本底值,直至仪器本底值低于检出限后进行样品测定. 每5个样品中插入正己烷空白,空白样品中均未检测到目标物. 在样品中加入替代标准品,所有血样和空白的两种替代标准的平均回收率在87.6%—150.2%之间,基质加标的相对标准偏差(RSD)小于10%. 目标化合物的检出限(LOD)定义为3倍信噪比,方法检出限范围为0.40—1.80 ng·mL−1.

1.5 数据处理

采用SPSS 22.0统计软件进行基础数据的处理和主成分分析、Origin 8.0软件进行数据分析和绘图.

2. 结果与讨论(Results and discussion)

2.1 PAHs、OPAHs暴露水平

本研究通过对血浆样品中PAHs及OPAHs进行分析,共检测到7种PAHs、检出率范围为17.8%—80.0%(如表2所示),与Yang等报道的PAHs检出率范围相似[8]. 在7种单体PAHs中,Phe的检出率最高(80.0%),其次是DBahA(66.7%),Koukoulakis等对希腊成年人血清的研究中也表明了Phe具有较高的检出率[9]. 其他单体PAHs检出率均低于50%,其中BghiP的检出率最低(17.8%).

表 2 PAH和OPAHs在血浆中的分布情况Table 2. Concentrations of PAH and OPAHs in plasma分类Species 物质名称Compound 检出率/%Detection rate 平均浓度/(ng·mL−1)Average concentration 范围/(ng·mL−1)Range 标准偏差/(ng·mL−1) Standard deviation PAHs Phe 80.0 10.8 N.d.—51.7 10.4 DBahA 66.7 14.2 N.d.—36.1 4.8 BghiP 17.8 1.4 N.d.—3.4 1.2 Flo 33.3 5.4 N.d.—15.6 3.6 Ant 26.7 2.3 N.d.—4.4 1.0 Flu 31.1 4.4 N.d.—14.1 3.4 Pyr 33.3 8.1 N.d.—25.2 6.0 ∑PAHs 100 24.8 10.1—111.2 17.4 OPAHs Dibf 28.9 8.9 N.d.—21.7 6.6 ATO 44.4 27.1 N.d.—56.0 7.5 Phe-9-Ald 66.7 6.7 N.d.—7.0 0.2 BZO 66.7 4.3 N.d.—5.3 0.5 NCQ 66.7 6.3 N.d.—9.2 1.4 7,12-BaAO 66.7 8.7 N.d.—13.5 1.7 ∑OPAHs 95.6 31.9 N.d.—85.5 21.6 ΣPAHs的浓度范围为10.1—111.2 ng·mL−1,平均值为24.8 ng·mL−1 (表2). 在检测到的单体PAHs中,DBahA、Phe具有较高的浓度(分别为14.2 ng·mL−1、10.8 ng·mL−1),也是其中检出率最高的2个单体PAHs,浓度最低的是BghiP(1.4 ng·mL−1). Koukoulakis等在血清中的研究发现Phe等7种PAHs的浓度范围为1.95—62.2 ng·mL−1(病例组)和1.26—48.6 ng·mL−1(控制组)[9];Singh等[10]对印度儿童血清PAHs检测的结果显示Phe、Ant、Flu、Pyr浓度分别为9.0 ng·mL−1、3.6 ng·mL−1、6.0 ng·mL−1和9.0 ng·mL−1. 本研究中的PAHs浓度范围上述两项研究中浓度范围基本一致.

在血浆样品中OPAHs的检出率为95.6%,其中Phe-9-Ald、BZO、NCQ、7,12-BaAOs的检出率较高(均大于60%),而Dibf的检出率最低(28.9%). Σ6OPAHs的浓度范围为Nd—85.5 ng·mL−1,平均值为31.9 ng·mL−1,在检测到的单体中,ATO具有最高的浓度(27.1 ng·mL−1),浓度最低的是BZO(4.3 ng·mL−1). 目前,国内外关于OPAHs的研究报道主要集中在环境介质中,动物、人体中OPAHs的研究报道较少,尚不能提供数据上的参照.

2.2 组分特征分析

血浆PAHs和OPAHs的分子组成从3环到6环均有分布,其中3环为Phe、Flo、Ant和ATO、Phe-9-Ald,占总量的56%,4环为Flu、Pyr和BZO、NCQ、7,12-BaAO,占总量的29%,5环和6环分别为DBahA和BghiP,分别占13.1%和1.3%(图1a). 血浆中检测到的PAHs和OPAHs成分主要以低-中分子量物质为主,Yin等在脐带血清的研究中发现了低分子量多环芳烃的比例高于高分子量多环芳烃[11],来自印度不同地区的多环芳烃监测研究也报告了儿童血清中低-中分子量多环芳烃多于高分子量多环芳烃[10],低-中-高分子量多环芳烃在人体中的分布呈现一致性. 该分布状况的形成与高分子量物质易与大颗粒物结合富集在地面,低中分子量物质易与较小的颗粒物结合悬浮在空气中有关,通过呼吸进入人体的低中环分子量物质较多,是导致血浆中PAHs和OPAHs以低中分子含量为主的重要因素之一.

在血浆样品中检测到的OPAHs浓度高于PAHs,分别占比56%和44%(图1b). 由于目前在人体内暴露中检测OPAHs的研究有限,目前在一些环境介质中的研究中,发现PAHs衍生物低于PAHs浓度;Bandowe等的研究报告称,乌兹别克斯坦一处工业区的土壤中多环芳烃衍生物(MPAHs,OPAH)的含量低于PAHs的含量[12];Wang等在北京大气颗粒中的研究中发现OPAHs的浓度低于PAHs[13],在环境中的调查与本研究结果不同. 据报道,多环芳烃衍生物与其母体PAHs相似,可以直接从岩源或热源中产生[14],此外,PAHs衍生物还可以通过PAHs在人体内的代谢而逐渐生成[15],这种转化可能是OPAHs的浓度高于PAHs的原因. 人体中出现OPAHs浓度较高的情况应引起重视,在有限的研究中表明OPAHs的毒性可能与PAHs的毒性相同甚至更高. OPAHs在细胞水平上的毒性作用能显著降低人脐静脉内皮细胞(HUVECs)一氧化氮(NO)的生成,存在潜在的内皮损伤效应,可成为人类细胞高致突变的诱变剂[16].

2.3 PAHs来源解析

2.3.1 特征值分析

由于不同的排放源会产生特定的多环芳烃标志物,PAHs特征比值法常被用来判别多环芳烃类污染物的可能来源. 本研究选用以往研究中广泛使用的4种特征值应用于本研究血清中PAHs的来源解析[9, 17-18]. 各类成因对应污染源中PAHs特征比值如表3所示,在本研究中通过特征值的分析,表明石油源和化石燃料的不完全燃烧是PAHs产生的的重要来源.

表 3 各类成因对应污染源中PAHs的特征比值Table 3. Various causes correspond to the diagnostics ratios of PAHs in pollution sources特征比值Diagnostics ratios 石油类来源Petroleum source 化石燃料的不完全燃烧类来源Incomplete combustion of fossil fuels 本研究This study 荧蒽/芘 Flu/Pyr 0—1 >1 0.55 菲/蒽 Phe/Ant >10 0—10 5.8 荧蒽/(荧蒽+芘) Flu/(Flu+Pyr) 0—0.4 0.4—0.5a,>0.5b 0.33 蒽/(蒽+菲) Ant/ (Phe+Ant) <0.1 >0.1 0.15 注:a. 主要在石油类产品的不完全燃烧过程中形成Mainly formed in the incomplete combustion process of petroleum products;b. 主要在木材、煤炭和草类的不完全燃烧过程中形成Mainly formed in the incomplete combustion process of wood, coal and grass 2.3.2 主成分分析

为进一步研究PAHs的来源情况,采用主成分分析法定量分析血浆中PAHs类物质的来源,提取初始特征值大于1的因子,2个主因子的累计方差贡献率为79.7%,7种PAHs主成分因子载荷如表4所示.

表 4 主成分分析因子载荷矩阵Table 4. Factor loading matrix of principal component analysis变量Variables 主因子1 Factor 1 主因子2 Factor 2 Flo −0.929 0.301 Phe −0.881 0.390 Ant −0.897 0.265 Flu −0.862 0.329 Pyr −0.899 0.317 DBahA 0.845 0.275 BghiP 0.262 0.379 Dibf −0.790 0.154 ATO 0.601 0.443 Phe-9-Ald 0.939 0.241 BZO 0.923 0.254 NCQ 0.894 0.258 7,12-BaAO 0.908 0.290 解释方差变量% 70.2 9.5 累计方差贡献率% 70.2 79.7 一般认为低分子量的PAHs主要来源于石油的泄漏、化石燃料和生物质的不完全燃烧,而高温燃烧过程主要形成高分子量的PAHs;如在PAHs的来源分析中Pyr、Phe等低中分子量主要与煤燃烧有关,DBahA、BghiP是汽车排放的重要化合物[19-21]. 主因子1具有最高的方差贡献率(70.2%),在主因子1的单体PAHs中只有DBahA具有很高的载荷,表明PAHs的来源是交通燃油排放;主因子2的方差贡献率为9.5%,在单体PAHs中Phe具有最高载荷,其次是Pyr、Flu等低分子量PAHs也具有较高载荷,表明燃煤是主因子2的主要来源. 本研究通过主成分分析表明交通燃油排放是主要污染源,而燃煤来源为PAHs的第二污染源. 其分析结果与特征比值法的结果相互吻合. 综上所述石油源和化石燃料的燃烧是PAHs产生的重要来源,通过对PAHs来源的解析有助于更好地了解排放途径和不同来源的贡献,为未来的风险管理提供科学依据.

有关OPAHs来源途径较多,即可来自于一次排放,也可来自于二次生成. 目前关于OPAHs的具体来源途径尚未有明确的判别方法,可供参考的研究资料有限,尚需进行进一步的研究工作,以期揭示OPAHs具体来源途径及其影响因素.

2.4 健康风险评估

2.4.1 每日总摄入量和毒性当量

依据药代动力学模型从血浆中多环芳烃含量推算每日总摄入量(TEDIs)如公式(1)所示,当血浆中的多环芳烃的浓度不在随时间变化时,即

dc/dt vdcdt=TEDIs×BW×A×f−b×V×C (1) 式中,C为血浆中单体多环芳烃的浓度;V为人体的血量(L),一般认为是男性血量为体重的8%;BW为体重(kg);A(无量纲)为Pyr摄入剂量的吸收速率为0.90;f(无量纲)是Pyr吸收剂量分布在血液中的比例为0.052;b代表Pyr的消除速率常数为0.068;式中这些参数参考Haddad[22]和Viau[23]的研究结果.

以血浆中Pyr浓度为基础,基于公式(1)计算血浆中Pyr的每日总摄入量. 其TEDI的范围为0.296—2.928 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw,平均浓度为0.935 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw,见表5.

表 5 Pyr的每日总摄入量(TEDI,μg·kg−1·d−1 bw)Table 5. Total estimated daily intake of Pyr in plasma (TEDI, μg·kg−1·d−1 bw)目标物Compounds 百分位数Percentiles 平均值Average 范围 Range 25% 50% 75% Pyr 0.487 0.777 1.156 0.935 0.296—2.928 由于每种单体PAHs具有不同程度的毒性,国内外的研究中通常采用苯并[a]芘当量浓度(BaP equivalent, BaPeq)来评估得到其他单体PAHs的毒性,各单体PAHs的BaPeq毒性当量计算公式如(2)所示。

BaPeqi=TEDIi×TEFi (2) 式中,BaPeqi为各PAHs单体的BaP当量毒性,TEFi为对应PAHs单体的毒性当量因子(Pyr的毒性当量因子为0.001).

2.4.2 非致癌健康风险和致癌风险

(1)非致癌系数(HQ)是每日摄入量(TEDI)与美国环保局提供每日参考剂量(RfD)的比值,若HQ>1,则说明存在非致癌风险;HQ<1,则表明不存在致癌风险[24]. Pyr的参考剂量为30 μg·kg−1-bw·d−1,计算公式如(3)所示.

HQ=TEDIRfD (3) (2)PAHs暴露的致癌风险的计算,如公式(4)所示。

CR=CSF×BaPeq (4) 式中,CSF为致癌斜率因子,本研究选用BaP的口服致癌斜率因子[8][7.3 (kg·d)·mg−1]. 根据美国环保署规定,CR<10−6时,引发的致癌风险不明显;CR在10−4和10−6之间时,表明具有潜在的致癌风险;CR>10−4时,表明存在很高的致癌风险[25].

分别计算了HQ和CR值(图2),以评估血浆中Pyr内暴露的非致癌和致癌风险. 血浆中Pyr的HQ值范围为0.072—0.712,中位数为0.189,表明人体血浆中的多环芳烃不存在非致癌风险. 然而,当考虑致癌风险时,基于苯并[a]芘当量浓度的致癌风险应引起足够关注,血浆中CR值的范围为2.16×10−6—2.14×10−5,中位数为5.67×10−6,所用个体的CR值均超过了1×10−6,表明血浆中PAHs存在潜在的致癌风险.

3. 结论(Conclusion)

在天津市45名青年人群血浆中共检测出7种PAHs和6种OPAHs,ΣPAHs和∑OPAHs平均浓度分别为24.8 ng·mL−1和31.9 ng·mL−1. 其单体化合物中ATO、DBahA的相对含量较高,对人群健康的潜在危害较大,应重点关注. 且PAHs和OPAHs组成特征以低中环物质为主,占总质量浓度的85%. 石油源和化石燃料的燃烧为人群血浆中PAHs的重要来源. 通过致癌风险评估,表明血浆中的PAHs存在潜在的致癌风险,后续应加大对人群内暴露的全面监测和长期健康风险的评估.

-

表 1 目标组分的检测离子

Table 1. The monitoring ions of target components

目标组分 Target component 定量离子 Quantifier ion (m/z) 定性离子 Qualifier ion (m/z) 芴 Fluorene(Flo) 166 165.00—164.00 菲 Phenanthrene(Phe) 178 176.00—152.00 蒽 Anthracene(Ant) 178 176.00—179.00 荧蒽 Fluoranthene(Flu) 202 200.00—203.00 芘 Pyrene(Pyr) 202 200.00—201.00 二苯并(a,h)蒽 Dibenz[a,h]anthracene(DBahA) 278 276.00—279.00 苯并(g,h,i)芘 Benzo[ghi]perylene(BghiP) 276 274.00—138.00 氧芴 Dibenzofuran(Dibf) 168 139.00—169.00 10H-9-蒽酮 10H-9-Anthracenone(ATQ) 208 152.00—180.00 菲-9-醛 Phenanthrene-9-carboxaldehyde(Phe-9-Ald) 178 206.00—176.00 苯并蒽酮 7H-Benz[de]anthracen-7-one(BZO) 230 202.00—200.00 5,12-四并苯醌 5,12-Naphthacenedione(NCQ) 258 202.00—230.00 苯并[a]蒽-7,12-二酮 Benz(a)anthracene-7,12-dione(7,12-BaAO) 258 202.00—230.00 菲-D10 Phenanthrene-D10(Phe-D10) 188 184.00—160.00 䓛-D12 Chrysene-D12(Chr-D12) 240 236.00—241.00 表 2 PAH和OPAHs在血浆中的分布情况

Table 2. Concentrations of PAH and OPAHs in plasma

分类Species 物质名称Compound 检出率/%Detection rate 平均浓度/(ng·mL−1)Average concentration 范围/(ng·mL−1)Range 标准偏差/(ng·mL−1) Standard deviation PAHs Phe 80.0 10.8 N.d.—51.7 10.4 DBahA 66.7 14.2 N.d.—36.1 4.8 BghiP 17.8 1.4 N.d.—3.4 1.2 Flo 33.3 5.4 N.d.—15.6 3.6 Ant 26.7 2.3 N.d.—4.4 1.0 Flu 31.1 4.4 N.d.—14.1 3.4 Pyr 33.3 8.1 N.d.—25.2 6.0 ∑PAHs 100 24.8 10.1—111.2 17.4 OPAHs Dibf 28.9 8.9 N.d.—21.7 6.6 ATO 44.4 27.1 N.d.—56.0 7.5 Phe-9-Ald 66.7 6.7 N.d.—7.0 0.2 BZO 66.7 4.3 N.d.—5.3 0.5 NCQ 66.7 6.3 N.d.—9.2 1.4 7,12-BaAO 66.7 8.7 N.d.—13.5 1.7 ∑OPAHs 95.6 31.9 N.d.—85.5 21.6 表 3 各类成因对应污染源中PAHs的特征比值

Table 3. Various causes correspond to the diagnostics ratios of PAHs in pollution sources

特征比值Diagnostics ratios 石油类来源Petroleum source 化石燃料的不完全燃烧类来源Incomplete combustion of fossil fuels 本研究This study 荧蒽/芘 Flu/Pyr 0—1 >1 0.55 菲/蒽 Phe/Ant >10 0—10 5.8 荧蒽/(荧蒽+芘) Flu/(Flu+Pyr) 0—0.4 0.4—0.5a,>0.5b 0.33 蒽/(蒽+菲) Ant/ (Phe+Ant) <0.1 >0.1 0.15 注:a. 主要在石油类产品的不完全燃烧过程中形成Mainly formed in the incomplete combustion process of petroleum products;b. 主要在木材、煤炭和草类的不完全燃烧过程中形成Mainly formed in the incomplete combustion process of wood, coal and grass 表 4 主成分分析因子载荷矩阵

Table 4. Factor loading matrix of principal component analysis

变量Variables 主因子1 Factor 1 主因子2 Factor 2 Flo −0.929 0.301 Phe −0.881 0.390 Ant −0.897 0.265 Flu −0.862 0.329 Pyr −0.899 0.317 DBahA 0.845 0.275 BghiP 0.262 0.379 Dibf −0.790 0.154 ATO 0.601 0.443 Phe-9-Ald 0.939 0.241 BZO 0.923 0.254 NCQ 0.894 0.258 7,12-BaAO 0.908 0.290 解释方差变量% 70.2 9.5 累计方差贡献率% 70.2 79.7 表 5 Pyr的每日总摄入量(TEDI,μg·kg−1·d−1 bw)

Table 5. Total estimated daily intake of Pyr in plasma (TEDI, μg·kg−1·d−1 bw)

目标物Compounds 百分位数Percentiles 平均值Average 范围 Range 25% 50% 75% Pyr 0.487 0.777 1.156 0.935 0.296—2.928 -

[1] KIM K H, JAHAN S A, KABIR E, et al. A review of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their human health effects [J]. Environment International, 2013, 60: 71-80. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.07.019 [2] BIENIEK G. Aromatic and polycyclic hydrocarbons in air and their urinary metabolites in coke plant workers [J]. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 1998, 34(5): 445-454. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199811)34:5<445::AID-AJIM5>3.0.CO;2-P [3] RENGARAJAN T, RAJENDRAN P, NANDAKUMAR N, et al. Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with special focus on cancer [J]. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 2015, 5(3): 182-189. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(15)30003-4 [4] GAN S, LAU E V, NG H K. Remediation of soils contaminated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2009, 172(2/3): 532-549. [5] RADMACHER P, MYERS S, LOONEY S, et al. A pilot study of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) in maternal and cord blood plasma [J]. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 2008, 56(1): 476-477. [6] PICKERING R W. A toxicological review of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [J]. Journal of Toxicology:Cutaneous and Ocular Toxicology, 1999, 18(2): 101-135. doi: 10.3109/15569529909037562 [7] MUSA BANDOWE B A, SOBOCKA J, WILCKE W. Oxygen-containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (OPAHs) in urban soils of Bratislava, Slovakia: Patterns, relation to PAHs and vertical distribution [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2011, 159(2): 539-549. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.10.011 [8] YANG Z Y, GUO C S, LI Q, et al. Human health risks estimations from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in serum and their hydroxylated metabolites in paired urine samples [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 290: 117975. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117975 [9] KOUKOULAKIS K G, KANELLOPOULOS P G, CHRYSOCHOU E, et al. Leukemia and PAHs levels in human blood serum: Preliminary results from an adult cohort in Greece [J]. Atmospheric Pollution Research, 2020, 11(9): 1552-1565. doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2020.06.018 [10] SINGH V K, PATEL D K, RAM S, et al. Blood levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in children of Lucknow, India [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2008, 54(2): 348-354. doi: 10.1007/s00244-007-9015-3 [11] YIN S S, TANG M L, CHEN F F, et al. Environmental exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): The correlation with and impact on reproductive hormones in umbilical cord serum [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 220: 1429-1437. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.10.090 [12] BANDOWE B A M, SHUKUROV N, LEIMER S, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soils of an industrial area in semi-arid Uzbekistan: Spatial distribution, relationship with trace metals and risk assessment [J]. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 2021, 43(11): 4847-4861. doi: 10.1007/s10653-021-00974-3 [13] WANG W T, JARIYASOPIT N, SCHRLAU J, et al. Concentration and photochemistry of PAHs, NPAHs, and OPAHs and toxicity of PM2.5 during the Beijing Olympic games [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(16): 6887-6895. [14] FORSBERG N D, WILSON G R, ANDERSON K A. Determination of parent and substituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in high-fat salmon using a modified QuEChERS extraction, dispersive SPE and GC-MS [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59(15): 8108-8116. doi: 10.1021/jf201745a [15] GEIER M C, CHLEBOWSKI A C, TRUONG L, et al. Comparative developmental toxicity of a comprehensive suite of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2018, 92(2): 571-586. doi: 10.1007/s00204-017-2068-9 [16] ØVREVIK J. Oxidative potential versus biological effects: A review on the relevance of cell-free/abiotic assays as predictors of toxicity from airborne particulate matter [J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2019, 20(19): 4772. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194772 [17] WHITEHEAD T, METAYER C, GUNIER R B, et al. Determinants of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon levels in house dust"> [J]. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 2011, 21(2): 123-132. [18] FANG G C, CHANG K F, LU C, et al. Estimation of PAHs dry deposition and BaP toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) study at Urban, Industry Park and rural sampling sites in central Taiwan, Taichung [J]. Chemosphere, 2004, 55(6): 787-796. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2003.12.012 [19] 陈锋, 孟凡生, 王业耀, 等. 基于主成分分析-多元线性回归的松花江水体中多环芳烃源解析 [J]. 中国环境监测, 2016, 32(4): 49-53. doi: 10.19316/j.issn.1002-6002.2016.04.09 CHEN F, MENG F S, WANG Y Y, et al. The research of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the river based on the principal component-multivariate linear regression analysis [J]. Environmental Monitoring in China, 2016, 32(4): 49-53(in Chinese). doi: 10.19316/j.issn.1002-6002.2016.04.09

[20] 何大双, 黄海平, 侯读杰, 等. 加拿大阿萨巴斯卡地区Mildred泥炭柱多环芳烃分布特征及来源解析 [J]. 湿地科学, 2019, 17(1): 25-35. doi: 10.13248/j.cnki.wetlandsci.2019.01.004 HE D S, HUANG H P, HOU D J, et al. Distribution characteristics and source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mildred peat core from the athabasca region, Canada [J]. Wetland Science, 2019, 17(1): 25-35(in Chinese). doi: 10.13248/j.cnki.wetlandsci.2019.01.004

[21] 党天剑, 陆光华, 薛晨旺, 等. 西藏色季拉山公路沿线PAHs分布、来源及风险 [J]. 中国环境科学, 2019, 39(3): 1109-1116. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6923.2019.03.026 DANG T J, LU G H, XUE C W, et al. Distribution, sources and risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons along the highway in Shergyla Mountain in Tibet [J]. China Environmental Science, 2019, 39(3): 1109-1116(in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6923.2019.03.026

[22] HADDAD S, WITHEY J, LAPARÉ S, et al. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modeling of Pyrene in the rat [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 1998, 5(4): 245-255. doi: 10.1016/S1382-6689(98)00008-8 [23] VIAU C, DIAKITÉ A, RUZGYTÉ A, et al. Is 1-hydroxypyrene a reliable bioindicator of measured dietary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon under normal conditions? [J]. Journal of Chromatography B, 2002, 778(1/2): 165-177. [24] LEI B L, ZHANG K Q, AN J, et al. Human health risk assessment of multiple contaminants due to consumption of animal-based foods available in the markets of Shanghai, China [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2015, 22(6): 4434-4446. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3683-0 [25] WANG W, HUANG M J, KANG Y, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in urban surface dust of Guangzhou, China: Status, sources and human health risk assessment [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2011, 409(21): 4519-4527. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.07.030 期刊类型引用(2)

1. 任瑛,李广科,桑楠. 氧化多环芳烃对大麦幼苗生长及抗氧化生理响应的影响. 环境化学. 2024(11): 3658-3664 .  本站查看

本站查看

2. 杨姝萍,钟芝清,黄子杰,罗宽能. 菜籽油中16种PAHs测定的不确定度评定. 粮油与饲料科技. 2024(10): 218-220 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(3)

-

DownLoad:

DownLoad: