-

我国生活垃圾焚烧行业发展迅猛,环境风险不容忽视。根据文献[1]以及我国生态环境部的公开数据,截至2022年,全球生活垃圾焚烧发电厂 (以下简称焚烧厂) 的焚烧规模约为1.41×106 t·d−1。其中,我国 (不含港澳台地区) 的焚烧规模为9.30×105 t·d−1,占比66.1%,排名第1,大于第2~4名欧盟 (2.07×104 t·d−1、占比14.7%) 、美国 (8.87×104 t·d−1、6.3%) 、日本 (9.22×104 t·d−1、6.5%) 的合计规模,且仍在增长。为防控相关环境风险,我国生态环境部在“十三五”期间启动了生活垃圾焚烧发电行业专项整治,采用了自动监测等诸多创新的手段和方法,出台了《生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据应用管理规定》 (生态环境部令第10号) 和《生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据标记规则》 (生态环境部公告2019年第50号) 等环境监管新政[2],建立了“互联网+全天候监管+非现场执法”模式,引导和督促焚烧厂提高烟气达标水平,使得全行业率先实现基本达标排放,取得了显著的环境效益、社会效益和经济效益,实现了精准治污、科学治污和依法治污,得到了社会的广泛认可[3-5]。

与此同时,部分省市为降低污染物排放总量,已经出台或正在推动更加严格的垃圾焚烧地方标准限值[6];此外,国家层面上积极推动县级地区垃圾焚烧处理设施覆盖范围向建制镇和乡村延伸[7]。与之有关的报道和议论进一步引发人们对生活垃圾焚烧烟气排放与监管标准的思考。1) 我国标准处于何种水平?2) 焚烧厂达标能力是否满足?3) 欧盟、美国、日本等发达国家 (地区) 的标准能否借鉴?

现有文献中对国内外垃圾焚烧排放与监管标准的对比仅关注了排放限值的数值差异,尚未深入分析国内外标准在历史沿革、基准条件、适用对象、执行尺度等方面的差异和原因,从而难以深入回答前述问题。本研究基于2017年以来国内生活垃圾焚烧行业专项整治取得的成效,深入分析国内外标准的差异及原因,有利于识别我国生活垃圾焚烧行业环境监管政策和模式与发达国家 (地区) 的差异,可为进一步优化固定源环境监管政策和模式提供依据。

-

欧盟 (含英国) 的焚烧厂主要建于1975年到2005年之间,到2013年已有约469座焚烧厂,焚烧规模约2.07×105 t·d−1,此后增长速度缓慢 [1, 8]。为了控制焚烧厂的烟气污染和环境风险,在焚烧规模发展到目前的1/3左右时,欧盟及成员国即开始细化烟气排放与监管的要求:1988年,奥地利首提烟气二噁英类的毒性当量浓度不超过0.1 ng TEQ·m−3的限值[9];1989年,欧盟 (欧共体) 发布《新建生活垃圾焚烧厂大气污染防治标准》 (Directive 89/369/EEC) [10],提出烟气在焚烧炉炉温850 ℃以上空间停留至少2 s、烟气含氧量 (氧气的体积分数) 不小于6%等工艺控制要求,为焚烧规模1 t·h−1以下、1~3 t·h−1、3 t·h−1以上的焚烧炉给出了差异化的限值,要求1 t·h−1以上焚烧炉的烟气含氧量、颗粒物、CO、HCl安装自动监测设备,使用7 d滑动均值、日均值开展污染物达标判定。关于烟气常规污染物达标评价的数据粒度,德国曾使用2 h均值和0.5 h最大值,荷兰曾使用最大1 h均值[9],但到1992年欧盟制定《危险废物焚烧污染控制标准提案》 (92/C130/01) 时已基本统一为日均值和0.5 h均值[11]。到20世纪末,欧盟在其1996年《环境空气质量评估和管理指令》 (Directive 96/62/EC) [12]等政策法规标准的影响下,发布了著名的“垃圾焚烧欧盟标准”《生活垃圾焚烧指令》 (Directive 2000/76/EC) [13]。10年后,该标准被欧盟《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) [14]替代,但垃圾焚烧的烟气排放限值并无变化。

-

与我国标准相比,欧盟现行标准《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) [14]存在以下异同:1) 基本条件一致,烟气基准含氧量均为11%,标准工况均指0 ℃和1个大气压;2) 欧盟标准纳入监管的烟气常规污染物指标更多,多出了HF和TOC;3) 欧盟标准中常规污染物达标评价的数据粒度包括日均值、0.5 h均值和10 min均值 (仅针对CO) ,日均值是1个自然日内所有0.5 h均值的算术平均值,且只允许最多5个无效的0.5 h均值,而在我国,日均值是1个自然日内所有1 h均值的算术平均值,且只允许最多4个无效的1 h均值[15];4) 欧盟标准的达标评价方式分为2种,一种需要评价时段内100%的自动监测0.5 h均值满足A类限值,另一种只需要97%以上的自动监测0.5 h均值满足更严格的B类限值,而我国的达标评价方式仅有前一种;5) 欧盟标准以6 t·h−1为界,对不同规模焚烧炉的NOx排放给出了差异化限值。

-

欧盟《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) 要求焚烧厂采用自动监测手段来证明7项常规污染物达标,但又给出了若干免于监测条件:1) 若可证明酸性气体 (HCl、HF和SO2) 稳定达标排放,则可不对酸性气体自动监测;2) 若焚烧规模小于144 t·d−1且可证明烟气NOx稳定达标排放,则可不对NOx自动监测[14]。在欧盟,颗粒物自动监测一般采用光透射/散射法,气态污染物自动监测可采用非分散红外光谱、傅里叶变换红外光谱、非分散紫外光谱、可调谐二极管激光吸收光谱等方法[16],每年开展至少1次比对监测。《固定源污染物自动监控系统的认定:性能要求与测试程序》 (EN 15267-3) 要求自动监测系统的准确度应在《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) 中规定偏差范围的基础上再收紧25%[17]。我国焚烧厂的烟气自动监测方法与欧盟相似,要求每年开展4次比对监测,对于监测指标没有设置免于监测条件[18]。

欧盟没有强制要求对烟气特征污染物开展自动监测:1) 烟气重金属除Hg可使用原子吸收光谱、差分吸收光谱等方法自动监测外,一般通过手工监测的方式来监管[16];2) 烟气二噁英类可手工监测,也可长周期采样监测。就二噁英类手工监测而言,欧盟的EN 1948系列标准和我国的HJ 77.2标准均采用高分辨率色谱质谱联用分析方法,需经历样品采集、提取、净化和仪器分析4个环节,单个样品采集时间一般为2 h,以使足够体积的烟气通过采样装置,提高检出效率。为解决二噁英类手工监测有限的采样时间难以覆盖垃圾焚烧工况波动的问题,欧盟从1997年开始探索使用长周期采样 (自动采样) 方式,通过改进烟气二噁英类采样装置,将采样时间从几个小时延长到2~4个星期,采集的样品仍然采用高分辨率色谱质谱联用分析方法。欧盟已制定《二噁英与多氯联苯长周期采样技术规范》 (CEN/TS 1948-5:2015)[19],法国、比利时等国以及我国宁波、台北等城市已实施了相关应用[20],全球约有450~500套长周期采样装置在使用。但是,长周期采样的容许监测误差较大,当样品的毒性当量浓度为0.02 ng TEQ·Nm−3时允许的最大误差100%,在实际监管应用中易受法理性掣肘。

-

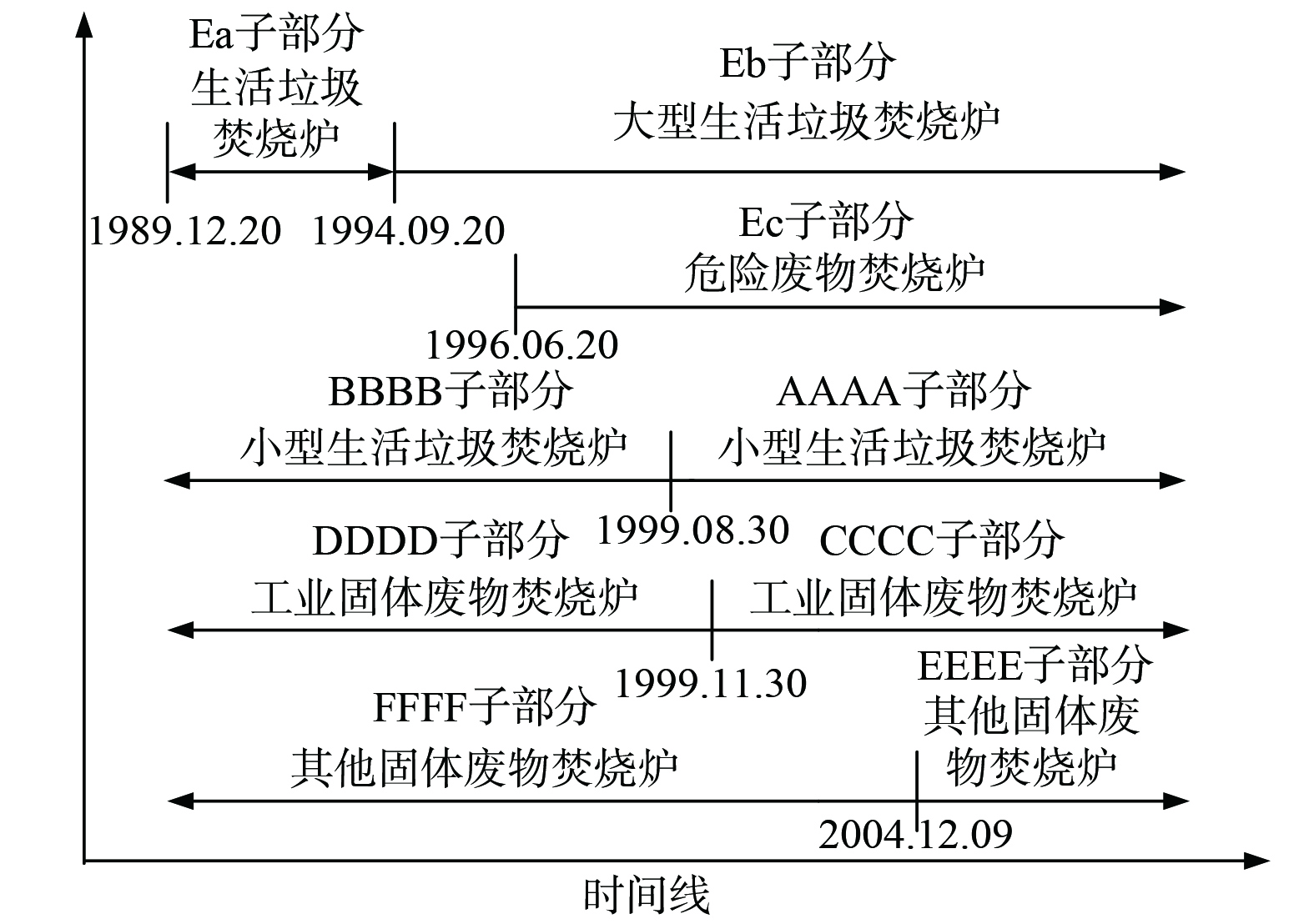

美国约有焚烧发电厂80座,焚烧规模约8.87×105 t·d−1,主要建成于1980年至1995年之间,集中在东海岸及五大湖地区;此外,全国仍有约1 300座不发电的小型焚烧炉存在[1, 21]。自从1995年美国《清洁空气法案》要求新建焚烧厂执行新的污染排放标准以来,便很少新建焚烧发电厂[1, 21]。美国焚烧炉的规模、技术水平、建设年代差异较大,使其排放与监管标准呈现十分显著的差异化特征。《美国联邦法典·环境保护·新建固定污染源环境标准》 (40 CFR part 60) [22]关于焚烧炉的规定共有9个子部分 (见图1) :Ea和Eb两个子部分,分别适用于1994年9月20日前后建成的大型生活垃圾焚烧炉 (≥250 ton·d−1) ;BBBB和AAAA两个子部分,分别适用于1999年8月30日前后建设的小型生活垃圾焚烧炉 (35 ton·d−1~250 ton·d−1) ;其他的子部分适用于危险废物焚烧炉或工业固体废物焚烧炉。其中,Eb子部分在2005年修订时进一步收严了烟气中颗粒物和重金属的排放限值。

-

美国《美国联邦法典·环境保护·新建固定污染源环境标准》 (40 CFR part 60) 的Ea、Eb、BBBB、AAAA等4个子部分均现行有效,这些子部分的排放限值差异主要体现在NOx、二噁英类两个方面。但是,美国标准的诸多基准条件与我国或欧盟不一致,包括:基准烟气含氧量为7%,标准状态是指20 ℃和1个大气压,重量单位使用美制短吨 (ton,1 ton≈0.907 t) ,常规污染物的排放限值使用体积浓度而非质量浓度,二噁英类的排放限值采用质量浓度而非毒性当量浓度,日均值计算采用几何平均而非算术平均。

-

美国早在1983年就在《美国联邦法典·环境保护·新建固定污染源环境标准》 (40 CFR part 60) 中构建了烟气自动监测的规范体系,1990年提出了焚烧厂自动监测的技术导则。因此,美国焚烧厂的环境监管广泛采用自动监测手段。40 CFR part 60的Eb子部分对大型焚烧炉烟气自动监测的要求包括:1) CO应自动监测,达标判定形式主要为4 h滑动平均值;2) 颗粒物、烟气浊度应自动监测,达标判定形式分别为日均值、6 min均值;3) SO2和NOx应自动监测,HCl可选自动监测,达标判定形式为日均值。40 CFR part 60的AAAA子部分也要求对小型焚烧炉的CO、HCl乃至NOx进行自动监测,但因小型焚烧炉的运行连续性较差,AAAA子部分、BBBB子部分要求污染物监测一般应覆盖3次运行过程。

-

日本自1975年起建设生活垃圾焚烧厂,但采取的是以二级行政区 (市、村、町、区,相当于我国的乡镇) 为单位的分散型建设模式,且焚烧发电厂占比不大。截至2021年,日本全国2 145个二级行政区共有热处理设施1 028座,相较往年略有减少,约2个二级行政区就有1座热处理设施 (其中焚烧发电厂384座,占比38.5%) [23]。日本焚烧厂布局分散、规模小 (焚烧炉单炉规模约为167 t·d−1) 、间歇式运行的较多,实际监管难度较大。受限于此,日本生活垃圾焚烧的污染排放标准相对宽松。

-

日本环境省《废弃物处理设施管理指南:垃圾焚烧设施 (第2版) 》给出了烟气中CO、NOx、HCl、二噁英类的排放限值,未直接给出SO2的排放限值,其烟气基准含氧量为12% [24]。根据该国《大气污染防止法》,焚烧厂烟气SO2的允许排放量和允许排放的质量浓度使用K值控制法或总量控制法来计算确定[25]。小型焚烧炉烟气二噁英类的排放限值较为宽松:(48~96) t·d−1焚烧炉的二恶英类限值为1 ng TEQ·Nm−3,48 t·d−1以下焚烧炉的二噁英类限值为5 ng TEQ·Nm−3。

-

日本标准中并未强调烟气污染物自动监测,仅要求每个固定源测2个样品,NOx、SO2、HCl的监测时间应大于30 min,CO的监测时间应大于4 h[24]。污染物自动监测应执行《烟道废气中二氧化硫的自动测量系统和分析仪》 (JIS B 7981) 等相关标准;自动监测设备校准维护应执行《气体分析装置校正方法通则》 (JIS K 0055) 等相关标准。

-

根据生态环境部生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据公开平台的信息,截至2022年,中国 (不包含港澳台地区) 已有834座焚烧发电厂,焚烧规模超过9.30×105 t·d−1,并仍在不断增长。我国生活垃圾焚烧烟气排放的监管要求经历了3个阶段。1) 2000年以前为萌芽探索阶段,国内生活垃圾焚烧规模整体不大,排放要求不完善。《小型焚烧炉》 (HJ/T 18—1996) 建立的限值体系纳入了颗粒物、CO、SO2、NOx、HCl等5项常规污染物,这一烟气排放限值体系沿用至今,但HJ/T 18—1996仅适用于500 kg·h−1以下小型焚烧炉的产品认证,且排放限值过于宽松。2) 2000至2019年为逐步完善阶段,国内生活垃圾焚烧规模不断增加,邻避压力不断增长,《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》先后发布为GWKB 3—2000、GB 18485—2001、GB 18485—2014及2019年修订单,明确提出炉温“850 ℃/2 s”的工艺控制要求,增加了重金属和二噁英类的排放限值,且不断收严排放限值。3) 2020年以来为精准监管阶段,《生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据应用管理规定》 (生态环境部令 第10号) 等环境监管新政实施,明确规定炉温及污染物排放的自动监测数据可作为环境执法证据,构建了依托自动监测手段的全天候精细化环境监管体系。

-

我国现行国家标准《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014及2019年修订单) 既提出了污染物排放控制要求,也提出了建设选址要求、设备选型要求、入炉废物要求、运行要求、监测要求和实施监督要求。与GB 18485—2001相比,GB 18485—2014收严了烟气排放限值,使得焚烧厂必须具备脱酸、脱硝、颗粒物捕集、特征污染物去除等烟气净化单元,还规定焚烧炉每年非正常工况下排放污染物的累计时长不得超过60 h,有利于提高焚烧厂环保水平。此外,上海、天津、河北、福建、海南、深圳等6个省 (市) 出台了排放限值比《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 更严的地方标准 (见表1) ,对HCl、SO2、NOx排放限值的最严要求分别比《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 严格87%、75%和73%。行业内普遍认为NOx排放限值收严的达标难度和成本最大。焚烧厂为了稳定达到地方标准,需要多措并举:1) 升级改造生产工艺和污染防治设施;2) 保证足量的环保耗材投加量;3) 增强运行维护精细化水平。

-

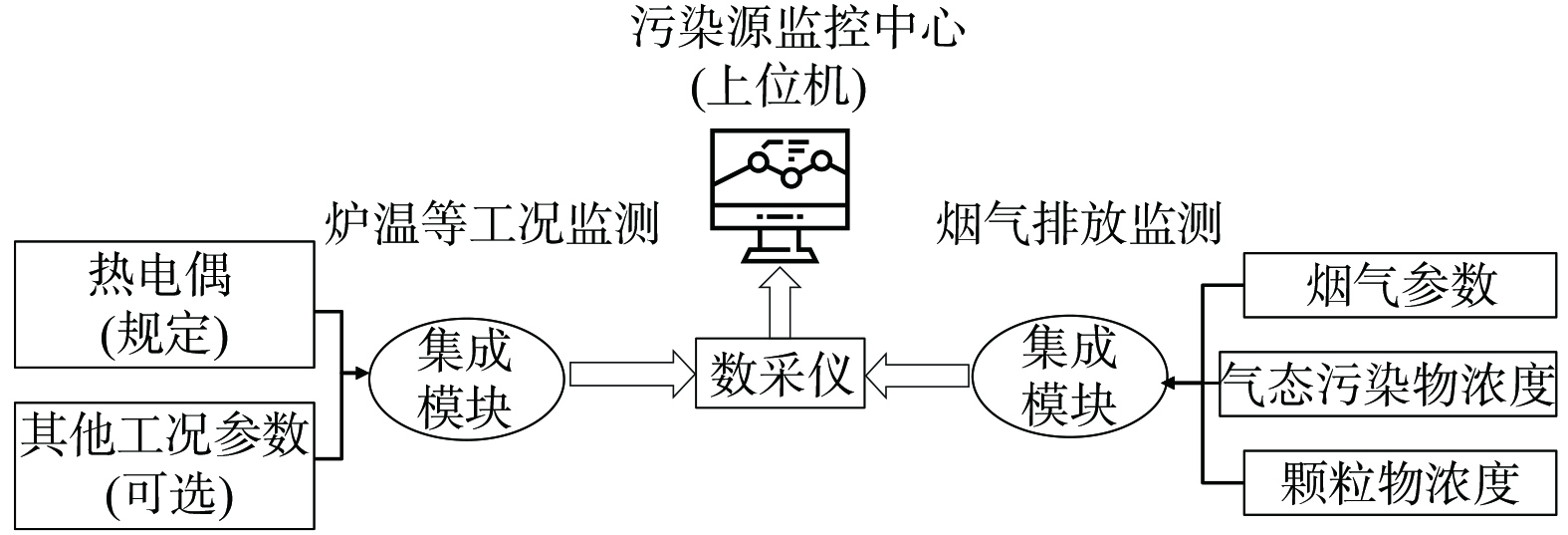

《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 规定焚烧厂安装烟气和炉温的自动监测设备。《环境保护部办公厅关于生活垃圾焚烧厂安装污染物排放自动监控设备和联网有关事项的通知》 (环办环监〔2017〕33号) 强化了安装自动监测设备的规定,要求焚烧厂完成“装、树、联”任务,即安装自动监测设备、厂门口树立显示屏、与生态环境部门联网。在此基础上,生态环境部令第10号等环境监管新政[2]建立了“互联网+全天候监管+非现场执法”模式以及以自动监测数据为驱动的环境监管机制 (见图2) 。一方面在管理层面上解决了炉温“850 ℃/2 s”、每年非正常工况不超过“60 h”等问题,提升了《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 的可操作性;另一方面通过全天候精细化实时监管,实现了对守法者无事不扰、对违法者精准打击,成为国内外环境监管中的一大创举[3-5]。

-

不同焚烧厂的运行工况条件存在差异,故需明确统一的折算基准用于比较烟气污染物的质量浓度 (或毒性当量浓度) ,以保证环境监管公平。从前文可知,我国和欧盟的折算基准一致,但与日本、美国差异较大,故不能直接比较。我国、欧盟焚烧厂烟气排放时的含氧量一般小于折算基准 (11%) ,亦即折算的质量浓度一般低于实测的质量浓度。之所以烟气含氧量的折算基准设置为11%,是因为考虑将垃圾焚烧时的过剩空气系数设为2.1,以保证垃圾焚烧“3T+E”条件[26]中的过剩空气 (excessive air) 条件。我国《生活垃圾焚烧处理工程技术规范》 (CJJ 90—2009) 、《生活垃圾焚烧厂运行监管标准》 (CJJ/T 212—2015) 等标准要求焚烧炉出口烟气含氧量控制在6%~10% (体积百分数) 之间[27],但未给出确切的编制依据。欧盟2006年版和2019年版的《垃圾焚烧最佳可行技术参考文档》[26, 28]提及了焚烧炉出口烟气含氧量不小于6%的要求,认为含氧量过小时不利于CO控制和设备防腐,但2个版本的说法不一致,2006年版文档认为这是已废除的早期要求,而2019年版文档又重申了这一要求;2个文档还提及了焚烧炉出口烟气含氧量介于6%~10%的说法,但引用的文献并未公开,难以考证。但在大量实际调研中了解到,对于大型机械炉排炉和烟气超低排放工艺来说,焚烧炉出口烟气含氧量低于6%可减少风机能耗和厂用电率,既具有明显的节能降耗效果,在运营管控良好的情况下也不会增加污染物的产生排放。

-

表1按照中国和欧盟的折算基准条件,将我国、欧盟、日本、美国的烟气污染物排放限值进行了折算和对比,以便于比较分析。从表1中可以看出:1) 各国标准监管的烟气污染物指标基本一致,虽然欧盟需监管HF和TOC,但并未成为美国、日本等国家的普适要求,这与标准执行的可操作性和实施成本是分不开的;2) 欧盟标准的排放限值最为严格,美国标准对酸性气体限制严格,但对CO和二噁英类的严格程度不如欧盟,日本老旧焚烧厂较多,故其标准对颗粒物、HCl的限制较为宽松;3) 我国《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 总体上处于严格行列,二噁英类的排放限值与欧盟一致,部分省份和城市甚至制定了严于欧盟的地方标准。

焚烧厂产生的污染物基本由垃圾燃料中的元素转化而成,除CO外,它们的生成浓度普遍有天然上限,只要采用合适的烟气净化措施并保证足额的耗材投入,就足以保证达标排放[1]。我国焚烧厂普遍将“选择性非催化还原 (SNCR) 脱硝+半干法脱酸+活性炭喷射+袋式除尘”作为烟气净化基本工艺,部分焚烧厂增设了选择性催化还原 (SCR) 脱硝、湿法脱酸等深度净化工艺。图3给出了我国焚烧厂2022年某月烟气常规污染物排放的质量浓度分布情况 (不包括根据生态环境部令第10号等环境监管新政[2]标记异常的数据) ,可以看出,我国焚烧厂正常运行期间的烟气污染物自动监测数据满足《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 的排放限值,各项烟气常规污染物指标排放质量浓度的大多数日均值数据距离标准排放限值还有一定的安全空间。另外,在保证焚烧工况正常的情况下,烟气二噁英类达标具备技术上的可行性,但是需要注重提高全过程协同防控水平,防范二噁英类的二次生成、记忆效应以及工况波动的影响[29-30]。

我国部分省份和城市,如上海、天津、河北、福建、海南和深圳等6个省市,结合区域发展水平和环境质量改善要求,制定了严于《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 的焚烧厂烟气排放与监管地方标准。表1中各项地方标准的排放限值具有以下特点:1) 除福建外的5项地方标准均收严了烟气颗粒物排放限值,这是因为除尘效率高的袋式除尘器已成为我国焚烧厂的标准配置,而低于20 mg·Nm−3的烟气颗粒物质量浓度的监测需遵循《固定污染源废气 低浓度颗粒物的测定 重量法》 (HJ 836—2017) 等方法;2) 6项地方标准均收严了烟气CO排放限值,这是因为对垃圾焚烧的燃烧完全度和工况稳定性提出了更高要求,从生态环境部生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据公开平台的信息来看,正常工况下炉排式焚烧炉的烟气CO排放质量浓度一般低于20 mg·Nm−3;3) 除福建外的5项地方标准均收严了烟气SO2和HCl的排放限值,从过去数十年的应用实践来看,通过半干法脱酸或者“半干法+干法”脱酸可以将烟气SO2排放质量浓度降低到基本满足表1中的地方标准要求,而要在烟气污染物质量浓度波动的情况下稳定满足地方标准中SO2和HCl的更严要求,则需要联用湿法脱酸措施;4) 6项地方标准均收严了烟气NOx排放限值,尤以深圳为甚,考虑到NOx的产生水平与烟气含氧量、燃料N含量、燃料N类型有关[6],而其削减水平与脱硝措施有关,行业内普遍认为需采用“SNCR脱硝+SCR脱硝”的方式才能将烟气NOx排放质量浓度降低到基本满足表1中的最严要求;5) 深圳、海南的地方标准均收严了烟气二噁英类的排放限值,这既需要完善“活性炭喷射+袋式除尘”的烟气净化措施,也需要防范二次生成、记忆效应、工况波动等可能导致烟气二噁英类产生水平增加的不利影响[29, 30]。

此外,我国《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 允许在不影响焚烧炉正常运行和污染物排放达标的前提下,将生活污水厂污泥、一般工业固体废物送入垃圾焚烧炉进行焚烧处置。入炉燃料成分的变化必然会带来烟气污染物产生水平的变化[1]:1) 生活污水厂污泥含水率高、灰分高、热值低,会导致烟气湿度增大、单位燃料的烟气量减少、烟气污染物的质量浓度水平升高,特别是会导致SO2和NOx的质量浓度水平升高,需控制入炉掺烧的比例;2) 一般工业固体废物含水率低、灰分低、热值高,往往会增大燃料的Cl元素含量和非厨余类N元素含量[6],有利于NOx控制但不利于HCl,除需控制入炉掺烧比例外,还需针对HCl可能的大幅波动做好补喷干粉脱酸、联用湿法脱酸等技术应对措施。

-

不同国家 (地区) 的焚烧厂发展历史不同、技术装备情况不同,使得烟气排放与监管标准的适用对象存在差异。欧盟、日本、美国等国家 (地区) 的烟气排放与监管标准为小型焚烧炉CO、NOx和二噁英类的排放限值设置了差异化的要求,相较而言:1) 欧盟的差异化要求最弱,仅将6 t·h−1以下焚烧炉的NOx排放限值放宽1倍;2) 日本的差异化要求比较明显,为2 t·h−1以下、2~4 t·h−1和4 t·h−1以上3种规模的焚烧炉给出了不同的排放限值,2 t·h−1以下焚烧炉二噁英类的排放限值放宽为5 ng TEQ·Nm−3,是4 t·h−1以上焚烧炉排放限值的50倍;3) 美国的差异化要求最为复杂,不同建设时段、不同规模的焚烧炉分别受不同的标准约束 (见图1) ,每个标准内部对于绝热炉墙炉排炉、水冷炉墙炉排炉、流化床等不同炉型又有不同的CO和NOx排放限值,CO、NOx和二噁英类的限值分别可相差2倍、2.7倍和8.6倍。

我国焚烧厂发展较晚,采用的技术装备相对成熟,《生活垃圾焚烧炉及余热锅炉》 (GB/T 18750—2008) [31]要求单炉规模一般不小于200 t·d−1,《生活垃圾焚烧处理工程项目建设标准》 (建标142—2010) 要求单炉规模不小于100 t·d−1,且全国所有具备发电能力的焚烧厂的单炉规模都在150 t·d−1以上,因此烟气排放与监管标准并未兼顾小型焚烧炉。但是,受到运输费用、无害化处理能力等因素的制约,在农村地区尤其是山区丘陵农村客观上存在数量不等的小型焚烧炉或小型热解气化焚烧炉[32-35];在国家发改委等部门的政策引导下,小型焚烧炉的数量和总体规模仍会增长[7]。对于小型焚烧炉来说,仅有《小型焚烧炉 技术条件》 (JB/T 10192—2012) 明确燃烧室工作温度、烟气出口温度、烟气停留时间、噪声等主要性能指标,在很长一段时间内缺乏相应的烟气排放与监管标准,所以这些小型焚烧炉纷纷自称能满足《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 的烟气污染物排放限值要求,而实际水平参差不齐[34, 36-37]。倘若我国能参照欧盟、日本、美国的标准,在充分调研小型焚烧炉或小型热解气化炉工况稳定性、污染排放水平、达标能力的基础上,在制修订相关的烟气排放与监管标准中给予小型焚烧炉合理的差异化要求,则有利于规范小型焚烧炉市场,增强环境监管的严肃性,但也应把握好尺度,避免像美国标准设置过于复杂的差异化要求,以免削弱标准执行的可操作性。

-

焚烧厂监管标准执行的严格程度决定标准的严肃性。2019年以前,我国的《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 虽然规定了焚烧炉非正常工况的时长限制,但在实施层面上监管措施不足,焚烧厂可“滤除”非正常工况期间的差数据,客观上增加了“劣币驱逐良币”的可能性。生态环境部令第10号等环境监管新政[2]充分发挥自动监测数据的全天候监管功能,创造性地提出了通过对自动监测数据进行电子化标记来声明非正常工况的方法,从而实时计算焚烧炉非正常工况的累积时长,仅对符合非正常工况时限要求的情形才不会认定污染物排放超标,杜绝了焚烧厂人为过滤“差数据”的可能性,真正实现了《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 第7.4条的落地实施。

不用于我国《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 以及生态环境部令第10号等环境监管新政[2]所强调的普适的、全天候的自动监测监管,欧盟标准允许焚烧厂在能证明酸性气体、NOx达标的前提下,不将相关指标纳入自动监测范围,美国允许焚烧厂不将HCl不纳入自动监测范围,执行弹性空间更大,这与欧美国家的经济社会水平和文化背景是分不开的。我国标准执行的弹性空间小,为体现公正、平等原则,实施全覆盖、无差别的环境监管,但这种模式会同时给监管主体和监管对象带来较大的负担,所以我国近年来也在探索“正面清单”[38]等更为灵活的监管方式。实际上,自动监测对违法者利剑高悬、守法者无事不扰的精准监管已经体现出一定的弹性特征,可进一步优化和拓展。一些地方也在借鉴欧盟《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) 中A、B两类限值的做法,在设置更严格排放限值的基础上,允许较小比例的自动监测数据超过限值,从而能适应合理的工况波动。例如,江苏省《固定式燃气轮机大气污染物排放标准》[39]设置的新建固定式燃气轮机NOx排放限值为15 mg·m−3,仅为欧盟《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) 相关限值的3/5,但规定自动监测数据日均值不应超过排放限值的110%、95%的1 h均值不应超过排放限值的200%。

当垃圾焚烧炉掺烧生活污水厂污泥、一般工业固体废物时,入炉燃料的不均质性增强,燃烧工况波动加剧,污染物排放超标的风险增加。这既需要焚烧厂做好入炉燃料特性检测,评估掺烧物料特性和比例对烟气污染物产生水平的影响,做好污染控制的应对措施;也需要在监管层面上合理考虑监管措施的弹性,在保证污染物自动监测得到的最小粒度数据真实、准确、完整、有效的基础上,可探索通过设置B类限值、考核污染物累积排放量等方式来适应工况波动对达标率的影响。

-

1) 我国、欧洲、日本、美国的标准监管的烟气污染物指标基本一致,欧盟标准的排放限值最为严格;我国《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 总体上处于严格行列,二噁英的排放限值与欧盟一致,且部分省份和城市已制定了严于欧盟的地方标准,烟气污染物排放具备满足排放与监管标准要求的技术可行性;

2) 欧盟、日本、美国的焚烧厂起步较早,技术装备差异性较大,烟气排放与监管标准表现较强的差异化特点,为小型焚烧炉的NOx和二噁英类设置了较强差异化的排放限值,但有的差异化要求过于繁复、不便操作;我国焚烧厂发展较晚,采用的技术装备相关成熟,监管标准没有兼顾小型焚烧炉,但确有必要给予小型焚烧炉适度、合理的差异化要求,以规范市场并增强环境监管的严肃性;

3) 欧盟、日本、美国的焚烧厂监管标准执行弹性空间较大,而我国的标准执行弹性空间小,为体现公正、平等原则,更习惯于开展全覆盖、无差别的监管,监管工作量较大、监管刚性很强但柔性不足,有必要在探索“正面清单”等更为灵活的监管方式的同时,基于自动监测手段表现出的精准监管能力,进一步优化和拓展更具弹性的排放限值与监管措施。

国内外生活垃圾焚烧烟气排放与监管标准比较分析

A comparison of emission and supervision standards on exhaust gas from municipal solid waste incineration in China and developed countries

-

摘要: 我国生活垃圾焚烧发电规模占全球的66.1%,环境风险不容忽视,需要制定适宜的烟气污染物排放限值与监管措施,可参考欧盟、美国、日本等较早应用生活垃圾焚烧处理的国家 (地区) 的有益经验。但是,现有的国内外对比研究仅关注了排放限值的差异,忽略了国内外标准在历史沿革、基准条件、适用对象、执行尺度等方面的差异及原因。本研究基于2017年以来国内生活垃圾焚烧行业专项整治取得的成效,深入分析国内外标准的差异及原因,得出以下结论:1) 烟气排放限值落地执行需要与之配套的监管措施,自动监测手段有利于实现对生活垃圾焚烧烟气常规污染物及炉温的全天候监管,在欧盟、美国已广泛应用,在我国的应用已取得良好成效;2) 与国外相比,我国生活垃圾焚烧烟气排放限值未考虑焚烧炉规模与技术差异化的影响,在排放与监管标准中未兼顾小型焚烧炉,但实际上有必要给予小型焚烧炉适度的、合理的差异化要求,以规范市场并增强环境监管的严肃性;3) 与国外相比,我国生活垃圾焚烧烟气排放限值总体上处于严格行列,监管刚性很强但柔性不足,部分省市制定的地方标准限值严于欧盟,但缺乏类似欧盟标准B类限值的达标评价方式,有必要在探索“正面清单”等更为灵活的监管方式的同时,基于自动监测手段表现出的精准监管能力,进一步优化和拓展更具弹性的排放限值与监管措施。本研究有利于识别我国生活垃圾焚烧行业环境监管政策和模式与发达国家 (地区) 的差异,可为进一步优化固定源环境监管政策和模式提供依据。Abstract: The scale of municipal solid waste (MSW) incineration of China accounts for 66.1% of the global total. The environmental risks cannot be neglected and appropriate emission limits and relevant supervision for exhaust gas pollutants should be established. Valuable experiences from countries (regions) that had earlier applications of waste incineration, such as European Union, the United States and Japan, can be considered. However, existing domestic and international comparative studies have only focused on the differences in emission limits stated by the standards, overlooking the differences and reasons for the historical evolution, baseline conditions, applicable targets, and severity of implementation. Based on the achievements of the rectification in waste incineration industry in China since 2017, this study thoroughly analyzed the differences and reasons for standards in China and foreign countries (regions), and drew the following conclusions. 1) The implementation of emission standards requires accompanying supervision measures. Automated monitoring methods were advantageous for achieving round-the-clock supervision of pollutants in exhaust gas. They have been widely adopted in Europe and the United States, and positive success was achieved in China as well. 2) Compared to foreign standards, the emission limit values for MSW incineration exhaust gas in China did not take into account the influences of scale differentiation. Small scale incinerators haven’t been adequately considered in standards for emissions and supervision. But it was necessary to provide moderate and rational differentiated requirements for them, in order to regulate the market and enhance the seriousness of environmental supervision. 3) Compared to foreign standards, the emission limit values for MSW incineration exhaust gas in China are relatively strict, with strong rigidity but insufficient flexibility. Some regional standards were more stringent than those in the European Union. However, there was a lack of benchmark assessment similar to the limits of Class B in EU standards. It was necessary to explore more flexible approaches such as "white lists" while further optimizing and expanding current emission standards and supervision methods based on the precision demonstrated by automated monitoring methods. This article is beneficial for clarifying the confidence in China’s supervision system in realms of waste incineration, and it provides a basis for further optimization in the policies and patterns for the environmental supervision of stationary sources.

-

Key words:

- waste incineration /

- supervision standards /

- emission limits /

- automated monitoring /

- dioxins

-

我国生活垃圾焚烧行业发展迅猛,环境风险不容忽视。根据文献[1]以及我国生态环境部的公开数据,截至2022年,全球生活垃圾焚烧发电厂 (以下简称焚烧厂) 的焚烧规模约为1.41×106 t·d−1。其中,我国 (不含港澳台地区) 的焚烧规模为9.30×105 t·d−1,占比66.1%,排名第1,大于第2~4名欧盟 (2.07×104 t·d−1、占比14.7%) 、美国 (8.87×104 t·d−1、6.3%) 、日本 (9.22×104 t·d−1、6.5%) 的合计规模,且仍在增长。为防控相关环境风险,我国生态环境部在“十三五”期间启动了生活垃圾焚烧发电行业专项整治,采用了自动监测等诸多创新的手段和方法,出台了《生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据应用管理规定》 (生态环境部令第10号) 和《生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据标记规则》 (生态环境部公告2019年第50号) 等环境监管新政[2],建立了“互联网+全天候监管+非现场执法”模式,引导和督促焚烧厂提高烟气达标水平,使得全行业率先实现基本达标排放,取得了显著的环境效益、社会效益和经济效益,实现了精准治污、科学治污和依法治污,得到了社会的广泛认可[3-5]。

与此同时,部分省市为降低污染物排放总量,已经出台或正在推动更加严格的垃圾焚烧地方标准限值[6];此外,国家层面上积极推动县级地区垃圾焚烧处理设施覆盖范围向建制镇和乡村延伸[7]。与之有关的报道和议论进一步引发人们对生活垃圾焚烧烟气排放与监管标准的思考。1) 我国标准处于何种水平?2) 焚烧厂达标能力是否满足?3) 欧盟、美国、日本等发达国家 (地区) 的标准能否借鉴?

现有文献中对国内外垃圾焚烧排放与监管标准的对比仅关注了排放限值的数值差异,尚未深入分析国内外标准在历史沿革、基准条件、适用对象、执行尺度等方面的差异和原因,从而难以深入回答前述问题。本研究基于2017年以来国内生活垃圾焚烧行业专项整治取得的成效,深入分析国内外标准的差异及原因,有利于识别我国生活垃圾焚烧行业环境监管政策和模式与发达国家 (地区) 的差异,可为进一步优化固定源环境监管政策和模式提供依据。

1. 烟气排放与监管要求

1.1 欧盟

1.1.1 历史沿革

欧盟 (含英国) 的焚烧厂主要建于1975年到2005年之间,到2013年已有约469座焚烧厂,焚烧规模约2.07×105 t·d−1,此后增长速度缓慢 [1, 8]。为了控制焚烧厂的烟气污染和环境风险,在焚烧规模发展到目前的1/3左右时,欧盟及成员国即开始细化烟气排放与监管的要求:1988年,奥地利首提烟气二噁英类的毒性当量浓度不超过0.1 ng TEQ·m−3的限值[9];1989年,欧盟 (欧共体) 发布《新建生活垃圾焚烧厂大气污染防治标准》 (Directive 89/369/EEC) [10],提出烟气在焚烧炉炉温850 ℃以上空间停留至少2 s、烟气含氧量 (氧气的体积分数) 不小于6%等工艺控制要求,为焚烧规模1 t·h−1以下、1~3 t·h−1、3 t·h−1以上的焚烧炉给出了差异化的限值,要求1 t·h−1以上焚烧炉的烟气含氧量、颗粒物、CO、HCl安装自动监测设备,使用7 d滑动均值、日均值开展污染物达标判定。关于烟气常规污染物达标评价的数据粒度,德国曾使用2 h均值和0.5 h最大值,荷兰曾使用最大1 h均值[9],但到1992年欧盟制定《危险废物焚烧污染控制标准提案》 (92/C130/01) 时已基本统一为日均值和0.5 h均值[11]。到20世纪末,欧盟在其1996年《环境空气质量评估和管理指令》 (Directive 96/62/EC) [12]等政策法规标准的影响下,发布了著名的“垃圾焚烧欧盟标准”《生活垃圾焚烧指令》 (Directive 2000/76/EC) [13]。10年后,该标准被欧盟《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) [14]替代,但垃圾焚烧的烟气排放限值并无变化。

1.1.2 现行标准

与我国标准相比,欧盟现行标准《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) [14]存在以下异同:1) 基本条件一致,烟气基准含氧量均为11%,标准工况均指0 ℃和1个大气压;2) 欧盟标准纳入监管的烟气常规污染物指标更多,多出了HF和TOC;3) 欧盟标准中常规污染物达标评价的数据粒度包括日均值、0.5 h均值和10 min均值 (仅针对CO) ,日均值是1个自然日内所有0.5 h均值的算术平均值,且只允许最多5个无效的0.5 h均值,而在我国,日均值是1个自然日内所有1 h均值的算术平均值,且只允许最多4个无效的1 h均值[15];4) 欧盟标准的达标评价方式分为2种,一种需要评价时段内100%的自动监测0.5 h均值满足A类限值,另一种只需要97%以上的自动监测0.5 h均值满足更严格的B类限值,而我国的达标评价方式仅有前一种;5) 欧盟标准以6 t·h−1为界,对不同规模焚烧炉的NOx排放给出了差异化限值。

1.1.3 监管手段

欧盟《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) 要求焚烧厂采用自动监测手段来证明7项常规污染物达标,但又给出了若干免于监测条件:1) 若可证明酸性气体 (HCl、HF和SO2) 稳定达标排放,则可不对酸性气体自动监测;2) 若焚烧规模小于144 t·d−1且可证明烟气NOx稳定达标排放,则可不对NOx自动监测[14]。在欧盟,颗粒物自动监测一般采用光透射/散射法,气态污染物自动监测可采用非分散红外光谱、傅里叶变换红外光谱、非分散紫外光谱、可调谐二极管激光吸收光谱等方法[16],每年开展至少1次比对监测。《固定源污染物自动监控系统的认定:性能要求与测试程序》 (EN 15267-3) 要求自动监测系统的准确度应在《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) 中规定偏差范围的基础上再收紧25%[17]。我国焚烧厂的烟气自动监测方法与欧盟相似,要求每年开展4次比对监测,对于监测指标没有设置免于监测条件[18]。

欧盟没有强制要求对烟气特征污染物开展自动监测:1) 烟气重金属除Hg可使用原子吸收光谱、差分吸收光谱等方法自动监测外,一般通过手工监测的方式来监管[16];2) 烟气二噁英类可手工监测,也可长周期采样监测。就二噁英类手工监测而言,欧盟的EN 1948系列标准和我国的HJ 77.2标准均采用高分辨率色谱质谱联用分析方法,需经历样品采集、提取、净化和仪器分析4个环节,单个样品采集时间一般为2 h,以使足够体积的烟气通过采样装置,提高检出效率。为解决二噁英类手工监测有限的采样时间难以覆盖垃圾焚烧工况波动的问题,欧盟从1997年开始探索使用长周期采样 (自动采样) 方式,通过改进烟气二噁英类采样装置,将采样时间从几个小时延长到2~4个星期,采集的样品仍然采用高分辨率色谱质谱联用分析方法。欧盟已制定《二噁英与多氯联苯长周期采样技术规范》 (CEN/TS 1948-5:2015)[19],法国、比利时等国以及我国宁波、台北等城市已实施了相关应用[20],全球约有450~500套长周期采样装置在使用。但是,长周期采样的容许监测误差较大,当样品的毒性当量浓度为0.02 ng TEQ·Nm−3时允许的最大误差100%,在实际监管应用中易受法理性掣肘。

1.2 美国

1.2.1 历史沿革

美国约有焚烧发电厂80座,焚烧规模约8.87×105 t·d−1,主要建成于1980年至1995年之间,集中在东海岸及五大湖地区;此外,全国仍有约1 300座不发电的小型焚烧炉存在[1, 21]。自从1995年美国《清洁空气法案》要求新建焚烧厂执行新的污染排放标准以来,便很少新建焚烧发电厂[1, 21]。美国焚烧炉的规模、技术水平、建设年代差异较大,使其排放与监管标准呈现十分显著的差异化特征。《美国联邦法典·环境保护·新建固定污染源环境标准》 (40 CFR part 60) [22]关于焚烧炉的规定共有9个子部分 (见图1) :Ea和Eb两个子部分,分别适用于1994年9月20日前后建成的大型生活垃圾焚烧炉 (≥250 ton·d−1) ;BBBB和AAAA两个子部分,分别适用于1999年8月30日前后建设的小型生活垃圾焚烧炉 (35 ton·d−1~250 ton·d−1) ;其他的子部分适用于危险废物焚烧炉或工业固体废物焚烧炉。其中,Eb子部分在2005年修订时进一步收严了烟气中颗粒物和重金属的排放限值。

1.2.2 现行标准

美国《美国联邦法典·环境保护·新建固定污染源环境标准》 (40 CFR part 60) 的Ea、Eb、BBBB、AAAA等4个子部分均现行有效,这些子部分的排放限值差异主要体现在NOx、二噁英类两个方面。但是,美国标准的诸多基准条件与我国或欧盟不一致,包括:基准烟气含氧量为7%,标准状态是指20 ℃和1个大气压,重量单位使用美制短吨 (ton,1 ton≈0.907 t) ,常规污染物的排放限值使用体积浓度而非质量浓度,二噁英类的排放限值采用质量浓度而非毒性当量浓度,日均值计算采用几何平均而非算术平均。

1.2.3 监管手段

美国早在1983年就在《美国联邦法典·环境保护·新建固定污染源环境标准》 (40 CFR part 60) 中构建了烟气自动监测的规范体系,1990年提出了焚烧厂自动监测的技术导则。因此,美国焚烧厂的环境监管广泛采用自动监测手段。40 CFR part 60的Eb子部分对大型焚烧炉烟气自动监测的要求包括:1) CO应自动监测,达标判定形式主要为4 h滑动平均值;2) 颗粒物、烟气浊度应自动监测,达标判定形式分别为日均值、6 min均值;3) SO2和NOx应自动监测,HCl可选自动监测,达标判定形式为日均值。40 CFR part 60的AAAA子部分也要求对小型焚烧炉的CO、HCl乃至NOx进行自动监测,但因小型焚烧炉的运行连续性较差,AAAA子部分、BBBB子部分要求污染物监测一般应覆盖3次运行过程。

1.3 日本

1.3.1 历史沿革

日本自1975年起建设生活垃圾焚烧厂,但采取的是以二级行政区 (市、村、町、区,相当于我国的乡镇) 为单位的分散型建设模式,且焚烧发电厂占比不大。截至2021年,日本全国2 145个二级行政区共有热处理设施1 028座,相较往年略有减少,约2个二级行政区就有1座热处理设施 (其中焚烧发电厂384座,占比38.5%) [23]。日本焚烧厂布局分散、规模小 (焚烧炉单炉规模约为167 t·d−1) 、间歇式运行的较多,实际监管难度较大。受限于此,日本生活垃圾焚烧的污染排放标准相对宽松。

1.3.2 现行标准

日本环境省《废弃物处理设施管理指南:垃圾焚烧设施 (第2版) 》给出了烟气中CO、NOx、HCl、二噁英类的排放限值,未直接给出SO2的排放限值,其烟气基准含氧量为12% [24]。根据该国《大气污染防止法》,焚烧厂烟气SO2的允许排放量和允许排放的质量浓度使用K值控制法或总量控制法来计算确定[25]。小型焚烧炉烟气二噁英类的排放限值较为宽松:(48~96) t·d−1焚烧炉的二恶英类限值为1 ng TEQ·Nm−3,48 t·d−1以下焚烧炉的二噁英类限值为5 ng TEQ·Nm−3。

1.3.3 监管手段

日本标准中并未强调烟气污染物自动监测,仅要求每个固定源测2个样品,NOx、SO2、HCl的监测时间应大于30 min,CO的监测时间应大于4 h[24]。污染物自动监测应执行《烟道废气中二氧化硫的自动测量系统和分析仪》 (JIS B 7981) 等相关标准;自动监测设备校准维护应执行《气体分析装置校正方法通则》 (JIS K 0055) 等相关标准。

1.4 中国

1.4.1 历史沿革

根据生态环境部生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据公开平台的信息,截至2022年,中国 (不包含港澳台地区) 已有834座焚烧发电厂,焚烧规模超过9.30×105 t·d−1,并仍在不断增长。我国生活垃圾焚烧烟气排放的监管要求经历了3个阶段。1) 2000年以前为萌芽探索阶段,国内生活垃圾焚烧规模整体不大,排放要求不完善。《小型焚烧炉》 (HJ/T 18—1996) 建立的限值体系纳入了颗粒物、CO、SO2、NOx、HCl等5项常规污染物,这一烟气排放限值体系沿用至今,但HJ/T 18—1996仅适用于500 kg·h−1以下小型焚烧炉的产品认证,且排放限值过于宽松。2) 2000至2019年为逐步完善阶段,国内生活垃圾焚烧规模不断增加,邻避压力不断增长,《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》先后发布为GWKB 3—2000、GB 18485—2001、GB 18485—2014及2019年修订单,明确提出炉温“850 ℃/2 s”的工艺控制要求,增加了重金属和二噁英类的排放限值,且不断收严排放限值。3) 2020年以来为精准监管阶段,《生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据应用管理规定》 (生态环境部令 第10号) 等环境监管新政实施,明确规定炉温及污染物排放的自动监测数据可作为环境执法证据,构建了依托自动监测手段的全天候精细化环境监管体系。

1.4.2 现行标准

我国现行国家标准《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014及2019年修订单) 既提出了污染物排放控制要求,也提出了建设选址要求、设备选型要求、入炉废物要求、运行要求、监测要求和实施监督要求。与GB 18485—2001相比,GB 18485—2014收严了烟气排放限值,使得焚烧厂必须具备脱酸、脱硝、颗粒物捕集、特征污染物去除等烟气净化单元,还规定焚烧炉每年非正常工况下排放污染物的累计时长不得超过60 h,有利于提高焚烧厂环保水平。此外,上海、天津、河北、福建、海南、深圳等6个省 (市) 出台了排放限值比《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 更严的地方标准 (见表1) ,对HCl、SO2、NOx排放限值的最严要求分别比《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 严格87%、75%和73%。行业内普遍认为NOx排放限值收严的达标难度和成本最大。焚烧厂为了稳定达到地方标准,需要多措并举:1) 升级改造生产工艺和污染防治设施;2) 保证足量的环保耗材投加量;3) 增强运行维护精细化水平。

表 1 不同国家 (地区) 生活垃圾焚烧烟气污染物排放限值对比Table 1. A comparison of flue gas emission limit from solid waste incineration facilities in different countries or regions国家或地区 排放要求 颗粒物/mg·Nm−3 CO/mg·Nm−3 SO2/mg·Nm−3 HCl/mg·Nm−3 NOx/mg·Nm−3 HF/mg·Nm−3 TOC/mg·Nm−3 Cd+Tl/mg·Nm−3 Hg/mg·Nm−3 Pb等/mg·Nm−3 二噁英类/ng I-TEQ·Nm−3 中国 《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 24 h均值 20 80 80 50 250 — — — — — — 1 h均值 30 100 100 60 300 — — — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.1 0.05 1 0.1 上海市《生活垃圾焚烧大气污染物排放标准》 (DB31/ 768—2013) 24 h均值 10 50 50 10 200 — — — — — — 1 h均值 10 100 100 50 250 — — — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.05 0.05 0.5 0.1 天津市《生活垃圾焚烧大气污染物排放标准》 (DB12/ 1101—2021) 24 h均值 8 50 20 10 80 — — — — — — 1 h均值 10 100 40 20 150 — — — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.03 0.02 0.3 0.1 河北省《生活垃圾焚烧大气污染排放标准》 (DB13/ 5325—2021) 24 h均值 8 80 20 10 120 — — — — — — 1 h均值 10 100 40 20 150 — — — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.03 0.02 0.3 0.1 福建省《生活垃圾焚烧氮氧化物排放标准》 (DB35/ 1976—2021) 新、改、扩建设施 24 h均值 — — — — 120 — — — — — — 1 h均值 — — — — 150 — — — — — — 海南省《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (DB46/ 484—2019) 24 h均值 8 30 20 8 120 1 10 — — — — 1 h均值 10 50 30 10 150 2 20 — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.03 0.02 0.3 0.05 深圳市《生活垃圾处理设施运营规范》 (SZDB/Z 233—2017) 新建设施 24 h均值 8 30 30 8 80 1 10 — — — — 1 h均值 10 50 30 8 80 2 10 — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.04 0.02 0.3 0.05 欧盟 《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) 日均值 10 50 50 10 200或400a 1 10 — — — — 0.5 h均值 (A类) 30 100 200 60 400 4 20 — — — — 0.5 h均值 (B类) 10 100 50 10 200 2 10 — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.05 0.05 0.5 0.1 日本b 《废弃物处理设施管理指南:垃圾焚烧设施 (第2版) 》 4t·h−1以上 44.4 41.7 视情况而定 777.8 570.4 — — — — — 0.11 美国c 40 CFR part 60,Ea子部分 26.1 48~144 65.7 31.2 283.4 — — — — — 0.38 40 CFR part 60,Eb子部分 2005年以前 18.4 48~144 65.7 31.2 236.1 — — 0.02 0.06 0.15 0.17 2005年以后 15.3 48~144 65.7 31.2 236.1 — — 0.01 0.04 0.11 0.17 40 CFR part 60,AAAA子部分 18.4 48~144 65.7 31.2 236~866 — — 0.02 0.06 0.02 0.17 40 CFR part 60,BBBB子部分 I类 20.7 48~240 67.9 38.7 268~598 — — 0.03 0.06 0.38 0.38或0.76 II类 53.7 48~240 168.7 312.3 — — — 0.08 0.06 1.23 1.60 注:a) 对于≤6 t·h−1的焚烧炉采用更宽松的限值;b) 已按烟气基准含氧量11%进行了折算;c) 已按烟气基准含氧量11%、标准状态为0 ℃进行了折算,污染物浓度已从体积浓度换算为质量浓度,二噁英类毒性当量浓度参照文献[9]按质量浓度除以60换算,重金属指标不同于中国和欧盟。 1.4.3 监管手段

《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 规定焚烧厂安装烟气和炉温的自动监测设备。《环境保护部办公厅关于生活垃圾焚烧厂安装污染物排放自动监控设备和联网有关事项的通知》 (环办环监〔2017〕33号) 强化了安装自动监测设备的规定,要求焚烧厂完成“装、树、联”任务,即安装自动监测设备、厂门口树立显示屏、与生态环境部门联网。在此基础上,生态环境部令第10号等环境监管新政[2]建立了“互联网+全天候监管+非现场执法”模式以及以自动监测数据为驱动的环境监管机制 (见图2) 。一方面在管理层面上解决了炉温“850 ℃/2 s”、每年非正常工况不超过“60 h”等问题,提升了《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 的可操作性;另一方面通过全天候精细化实时监管,实现了对守法者无事不扰、对违法者精准打击,成为国内外环境监管中的一大创举[3-5]。

图 2 我国生活垃圾焚烧发电行业的自动监控系统 (引自文献[2])Figure 2. Automated supervision system of solid waste incineration facilities in China

图 2 我国生活垃圾焚烧发电行业的自动监控系统 (引自文献[2])Figure 2. Automated supervision system of solid waste incineration facilities in China2. 比较分析

2.1 折算基准

不同焚烧厂的运行工况条件存在差异,故需明确统一的折算基准用于比较烟气污染物的质量浓度 (或毒性当量浓度) ,以保证环境监管公平。从前文可知,我国和欧盟的折算基准一致,但与日本、美国差异较大,故不能直接比较。我国、欧盟焚烧厂烟气排放时的含氧量一般小于折算基准 (11%) ,亦即折算的质量浓度一般低于实测的质量浓度。之所以烟气含氧量的折算基准设置为11%,是因为考虑将垃圾焚烧时的过剩空气系数设为2.1,以保证垃圾焚烧“3T+E”条件[26]中的过剩空气 (excessive air) 条件。我国《生活垃圾焚烧处理工程技术规范》 (CJJ 90—2009) 、《生活垃圾焚烧厂运行监管标准》 (CJJ/T 212—2015) 等标准要求焚烧炉出口烟气含氧量控制在6%~10% (体积百分数) 之间[27],但未给出确切的编制依据。欧盟2006年版和2019年版的《垃圾焚烧最佳可行技术参考文档》[26, 28]提及了焚烧炉出口烟气含氧量不小于6%的要求,认为含氧量过小时不利于CO控制和设备防腐,但2个版本的说法不一致,2006年版文档认为这是已废除的早期要求,而2019年版文档又重申了这一要求;2个文档还提及了焚烧炉出口烟气含氧量介于6%~10%的说法,但引用的文献并未公开,难以考证。但在大量实际调研中了解到,对于大型机械炉排炉和烟气超低排放工艺来说,焚烧炉出口烟气含氧量低于6%可减少风机能耗和厂用电率,既具有明显的节能降耗效果,在运营管控良好的情况下也不会增加污染物的产生排放。

2.2 可达性

表1按照中国和欧盟的折算基准条件,将我国、欧盟、日本、美国的烟气污染物排放限值进行了折算和对比,以便于比较分析。从表1中可以看出:1) 各国标准监管的烟气污染物指标基本一致,虽然欧盟需监管HF和TOC,但并未成为美国、日本等国家的普适要求,这与标准执行的可操作性和实施成本是分不开的;2) 欧盟标准的排放限值最为严格,美国标准对酸性气体限制严格,但对CO和二噁英类的严格程度不如欧盟,日本老旧焚烧厂较多,故其标准对颗粒物、HCl的限制较为宽松;3) 我国《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 总体上处于严格行列,二噁英类的排放限值与欧盟一致,部分省份和城市甚至制定了严于欧盟的地方标准。

焚烧厂产生的污染物基本由垃圾燃料中的元素转化而成,除CO外,它们的生成浓度普遍有天然上限,只要采用合适的烟气净化措施并保证足额的耗材投入,就足以保证达标排放[1]。我国焚烧厂普遍将“选择性非催化还原 (SNCR) 脱硝+半干法脱酸+活性炭喷射+袋式除尘”作为烟气净化基本工艺,部分焚烧厂增设了选择性催化还原 (SCR) 脱硝、湿法脱酸等深度净化工艺。图3给出了我国焚烧厂2022年某月烟气常规污染物排放的质量浓度分布情况 (不包括根据生态环境部令第10号等环境监管新政[2]标记异常的数据) ,可以看出,我国焚烧厂正常运行期间的烟气污染物自动监测数据满足《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 的排放限值,各项烟气常规污染物指标排放质量浓度的大多数日均值数据距离标准排放限值还有一定的安全空间。另外,在保证焚烧工况正常的情况下,烟气二噁英类达标具备技术上的可行性,但是需要注重提高全过程协同防控水平,防范二噁英类的二次生成、记忆效应以及工况波动的影响[29-30]。

我国部分省份和城市,如上海、天津、河北、福建、海南和深圳等6个省市,结合区域发展水平和环境质量改善要求,制定了严于《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 的焚烧厂烟气排放与监管地方标准。表1中各项地方标准的排放限值具有以下特点:1) 除福建外的5项地方标准均收严了烟气颗粒物排放限值,这是因为除尘效率高的袋式除尘器已成为我国焚烧厂的标准配置,而低于20 mg·Nm−3的烟气颗粒物质量浓度的监测需遵循《固定污染源废气 低浓度颗粒物的测定 重量法》 (HJ 836—2017) 等方法;2) 6项地方标准均收严了烟气CO排放限值,这是因为对垃圾焚烧的燃烧完全度和工况稳定性提出了更高要求,从生态环境部生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据公开平台的信息来看,正常工况下炉排式焚烧炉的烟气CO排放质量浓度一般低于20 mg·Nm−3;3) 除福建外的5项地方标准均收严了烟气SO2和HCl的排放限值,从过去数十年的应用实践来看,通过半干法脱酸或者“半干法+干法”脱酸可以将烟气SO2排放质量浓度降低到基本满足表1中的地方标准要求,而要在烟气污染物质量浓度波动的情况下稳定满足地方标准中SO2和HCl的更严要求,则需要联用湿法脱酸措施;4) 6项地方标准均收严了烟气NOx排放限值,尤以深圳为甚,考虑到NOx的产生水平与烟气含氧量、燃料N含量、燃料N类型有关[6],而其削减水平与脱硝措施有关,行业内普遍认为需采用“SNCR脱硝+SCR脱硝”的方式才能将烟气NOx排放质量浓度降低到基本满足表1中的最严要求;5) 深圳、海南的地方标准均收严了烟气二噁英类的排放限值,这既需要完善“活性炭喷射+袋式除尘”的烟气净化措施,也需要防范二次生成、记忆效应、工况波动等可能导致烟气二噁英类产生水平增加的不利影响[29, 30]。

此外,我国《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 允许在不影响焚烧炉正常运行和污染物排放达标的前提下,将生活污水厂污泥、一般工业固体废物送入垃圾焚烧炉进行焚烧处置。入炉燃料成分的变化必然会带来烟气污染物产生水平的变化[1]:1) 生活污水厂污泥含水率高、灰分高、热值低,会导致烟气湿度增大、单位燃料的烟气量减少、烟气污染物的质量浓度水平升高,特别是会导致SO2和NOx的质量浓度水平升高,需控制入炉掺烧的比例;2) 一般工业固体废物含水率低、灰分低、热值高,往往会增大燃料的Cl元素含量和非厨余类N元素含量[6],有利于NOx控制但不利于HCl,除需控制入炉掺烧比例外,还需针对HCl可能的大幅波动做好补喷干粉脱酸、联用湿法脱酸等技术应对措施。

2.3 适用对象

不同国家 (地区) 的焚烧厂发展历史不同、技术装备情况不同,使得烟气排放与监管标准的适用对象存在差异。欧盟、日本、美国等国家 (地区) 的烟气排放与监管标准为小型焚烧炉CO、NOx和二噁英类的排放限值设置了差异化的要求,相较而言:1) 欧盟的差异化要求最弱,仅将6 t·h−1以下焚烧炉的NOx排放限值放宽1倍;2) 日本的差异化要求比较明显,为2 t·h−1以下、2~4 t·h−1和4 t·h−1以上3种规模的焚烧炉给出了不同的排放限值,2 t·h−1以下焚烧炉二噁英类的排放限值放宽为5 ng TEQ·Nm−3,是4 t·h−1以上焚烧炉排放限值的50倍;3) 美国的差异化要求最为复杂,不同建设时段、不同规模的焚烧炉分别受不同的标准约束 (见图1) ,每个标准内部对于绝热炉墙炉排炉、水冷炉墙炉排炉、流化床等不同炉型又有不同的CO和NOx排放限值,CO、NOx和二噁英类的限值分别可相差2倍、2.7倍和8.6倍。

我国焚烧厂发展较晚,采用的技术装备相对成熟,《生活垃圾焚烧炉及余热锅炉》 (GB/T 18750—2008) [31]要求单炉规模一般不小于200 t·d−1,《生活垃圾焚烧处理工程项目建设标准》 (建标142—2010) 要求单炉规模不小于100 t·d−1,且全国所有具备发电能力的焚烧厂的单炉规模都在150 t·d−1以上,因此烟气排放与监管标准并未兼顾小型焚烧炉。但是,受到运输费用、无害化处理能力等因素的制约,在农村地区尤其是山区丘陵农村客观上存在数量不等的小型焚烧炉或小型热解气化焚烧炉[32-35];在国家发改委等部门的政策引导下,小型焚烧炉的数量和总体规模仍会增长[7]。对于小型焚烧炉来说,仅有《小型焚烧炉 技术条件》 (JB/T 10192—2012) 明确燃烧室工作温度、烟气出口温度、烟气停留时间、噪声等主要性能指标,在很长一段时间内缺乏相应的烟气排放与监管标准,所以这些小型焚烧炉纷纷自称能满足《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 的烟气污染物排放限值要求,而实际水平参差不齐[34, 36-37]。倘若我国能参照欧盟、日本、美国的标准,在充分调研小型焚烧炉或小型热解气化炉工况稳定性、污染排放水平、达标能力的基础上,在制修订相关的烟气排放与监管标准中给予小型焚烧炉合理的差异化要求,则有利于规范小型焚烧炉市场,增强环境监管的严肃性,但也应把握好尺度,避免像美国标准设置过于复杂的差异化要求,以免削弱标准执行的可操作性。

2.4 执行尺度

焚烧厂监管标准执行的严格程度决定标准的严肃性。2019年以前,我国的《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 虽然规定了焚烧炉非正常工况的时长限制,但在实施层面上监管措施不足,焚烧厂可“滤除”非正常工况期间的差数据,客观上增加了“劣币驱逐良币”的可能性。生态环境部令第10号等环境监管新政[2]充分发挥自动监测数据的全天候监管功能,创造性地提出了通过对自动监测数据进行电子化标记来声明非正常工况的方法,从而实时计算焚烧炉非正常工况的累积时长,仅对符合非正常工况时限要求的情形才不会认定污染物排放超标,杜绝了焚烧厂人为过滤“差数据”的可能性,真正实现了《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 第7.4条的落地实施。

不用于我国《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 以及生态环境部令第10号等环境监管新政[2]所强调的普适的、全天候的自动监测监管,欧盟标准允许焚烧厂在能证明酸性气体、NOx达标的前提下,不将相关指标纳入自动监测范围,美国允许焚烧厂不将HCl不纳入自动监测范围,执行弹性空间更大,这与欧美国家的经济社会水平和文化背景是分不开的。我国标准执行的弹性空间小,为体现公正、平等原则,实施全覆盖、无差别的环境监管,但这种模式会同时给监管主体和监管对象带来较大的负担,所以我国近年来也在探索“正面清单”[38]等更为灵活的监管方式。实际上,自动监测对违法者利剑高悬、守法者无事不扰的精准监管已经体现出一定的弹性特征,可进一步优化和拓展。一些地方也在借鉴欧盟《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) 中A、B两类限值的做法,在设置更严格排放限值的基础上,允许较小比例的自动监测数据超过限值,从而能适应合理的工况波动。例如,江苏省《固定式燃气轮机大气污染物排放标准》[39]设置的新建固定式燃气轮机NOx排放限值为15 mg·m−3,仅为欧盟《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) 相关限值的3/5,但规定自动监测数据日均值不应超过排放限值的110%、95%的1 h均值不应超过排放限值的200%。

当垃圾焚烧炉掺烧生活污水厂污泥、一般工业固体废物时,入炉燃料的不均质性增强,燃烧工况波动加剧,污染物排放超标的风险增加。这既需要焚烧厂做好入炉燃料特性检测,评估掺烧物料特性和比例对烟气污染物产生水平的影响,做好污染控制的应对措施;也需要在监管层面上合理考虑监管措施的弹性,在保证污染物自动监测得到的最小粒度数据真实、准确、完整、有效的基础上,可探索通过设置B类限值、考核污染物累积排放量等方式来适应工况波动对达标率的影响。

3. 结论

1) 我国、欧洲、日本、美国的标准监管的烟气污染物指标基本一致,欧盟标准的排放限值最为严格;我国《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 总体上处于严格行列,二噁英的排放限值与欧盟一致,且部分省份和城市已制定了严于欧盟的地方标准,烟气污染物排放具备满足排放与监管标准要求的技术可行性;

2) 欧盟、日本、美国的焚烧厂起步较早,技术装备差异性较大,烟气排放与监管标准表现较强的差异化特点,为小型焚烧炉的NOx和二噁英类设置了较强差异化的排放限值,但有的差异化要求过于繁复、不便操作;我国焚烧厂发展较晚,采用的技术装备相关成熟,监管标准没有兼顾小型焚烧炉,但确有必要给予小型焚烧炉适度、合理的差异化要求,以规范市场并增强环境监管的严肃性;

3) 欧盟、日本、美国的焚烧厂监管标准执行弹性空间较大,而我国的标准执行弹性空间小,为体现公正、平等原则,更习惯于开展全覆盖、无差别的监管,监管工作量较大、监管刚性很强但柔性不足,有必要在探索“正面清单”等更为灵活的监管方式的同时,基于自动监测手段表现出的精准监管能力,进一步优化和拓展更具弹性的排放限值与监管措施。

-

图 2 我国生活垃圾焚烧发电行业的自动监控系统 (引自文献[2])

Figure 2. Automated supervision system of solid waste incineration facilities in China

表 1 不同国家 (地区) 生活垃圾焚烧烟气污染物排放限值对比

Table 1. A comparison of flue gas emission limit from solid waste incineration facilities in different countries or regions

国家或地区 排放要求 颗粒物/mg·Nm−3 CO/mg·Nm−3 SO2/mg·Nm−3 HCl/mg·Nm−3 NOx/mg·Nm−3 HF/mg·Nm−3 TOC/mg·Nm−3 Cd+Tl/mg·Nm−3 Hg/mg·Nm−3 Pb等/mg·Nm−3 二噁英类/ng I-TEQ·Nm−3 中国 《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (GB 18485—2014) 24 h均值 20 80 80 50 250 — — — — — — 1 h均值 30 100 100 60 300 — — — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.1 0.05 1 0.1 上海市《生活垃圾焚烧大气污染物排放标准》 (DB31/ 768—2013) 24 h均值 10 50 50 10 200 — — — — — — 1 h均值 10 100 100 50 250 — — — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.05 0.05 0.5 0.1 天津市《生活垃圾焚烧大气污染物排放标准》 (DB12/ 1101—2021) 24 h均值 8 50 20 10 80 — — — — — — 1 h均值 10 100 40 20 150 — — — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.03 0.02 0.3 0.1 河北省《生活垃圾焚烧大气污染排放标准》 (DB13/ 5325—2021) 24 h均值 8 80 20 10 120 — — — — — — 1 h均值 10 100 40 20 150 — — — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.03 0.02 0.3 0.1 福建省《生活垃圾焚烧氮氧化物排放标准》 (DB35/ 1976—2021) 新、改、扩建设施 24 h均值 — — — — 120 — — — — — — 1 h均值 — — — — 150 — — — — — — 海南省《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》 (DB46/ 484—2019) 24 h均值 8 30 20 8 120 1 10 — — — — 1 h均值 10 50 30 10 150 2 20 — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.03 0.02 0.3 0.05 深圳市《生活垃圾处理设施运营规范》 (SZDB/Z 233—2017) 新建设施 24 h均值 8 30 30 8 80 1 10 — — — — 1 h均值 10 50 30 8 80 2 10 — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.04 0.02 0.3 0.05 欧盟 《工业排放指令》 (Directive 2010/75/EU) 日均值 10 50 50 10 200或400a 1 10 — — — — 0.5 h均值 (A类) 30 100 200 60 400 4 20 — — — — 0.5 h均值 (B类) 10 100 50 10 200 2 10 — — — — 测定均值 — — — — — — — 0.05 0.05 0.5 0.1 日本b 《废弃物处理设施管理指南:垃圾焚烧设施 (第2版) 》 4t·h−1以上 44.4 41.7 视情况而定 777.8 570.4 — — — — — 0.11 美国c 40 CFR part 60,Ea子部分 26.1 48~144 65.7 31.2 283.4 — — — — — 0.38 40 CFR part 60,Eb子部分 2005年以前 18.4 48~144 65.7 31.2 236.1 — — 0.02 0.06 0.15 0.17 2005年以后 15.3 48~144 65.7 31.2 236.1 — — 0.01 0.04 0.11 0.17 40 CFR part 60,AAAA子部分 18.4 48~144 65.7 31.2 236~866 — — 0.02 0.06 0.02 0.17 40 CFR part 60,BBBB子部分 I类 20.7 48~240 67.9 38.7 268~598 — — 0.03 0.06 0.38 0.38或0.76 II类 53.7 48~240 168.7 312.3 — — — 0.08 0.06 1.23 1.60 注:a) 对于≤6 t·h−1的焚烧炉采用更宽松的限值;b) 已按烟气基准含氧量11%进行了折算;c) 已按烟气基准含氧量11%、标准状态为0 ℃进行了折算,污染物浓度已从体积浓度换算为质量浓度,二噁英类毒性当量浓度参照文献[9]按质量浓度除以60换算,重金属指标不同于中国和欧盟。 -

[1] LU J W, ZHANG S, HAI J, et al. Status and perspectives of municipal solid waste incineration in China: A comparison with developed regions[J]. Waste Management, 2017, 69(C): 170-186. [2] 生态环境部生态环境执法局, 生态环境部华南环境科学研究所. 生活垃圾焚烧发电厂自动监测数据管理新政解读[M]. 北京: 中国环境出版集团, 2020. [3] 于天昊. 垃圾焚烧发电行业如何做到“华丽转身”?[N]. 中国环境报, 2021-03-15(1). [4] 陈郁. 我国垃圾焚烧发电行业专项整治取得显著成效, 自动监测数据立功[N]. 经济日报, 2021-01-04. [5] 王玮, 郭建兵. 垃圾焚烧发电行业专项整治行动成效系列报道(5)垃圾焚烧发电——可供世界借鉴的中国方案[J]. 环境经济, 2023(1): 52-55. [6] 沈华鑫, 程江, 谢颖诗, 等. 垃圾分类背景下厨余垃圾剔除比例对生活垃圾焚烧厂NOx排放的影响[J]. 环境工程学报, 2021, 15(12): 3957-3966. [7] 发展改革委, 住房城乡建设部, 生态环境部, 等. 国家发展改革委等部门关于加强县级地区生活垃圾焚烧处理设施建设的指导意见(发改环资〔2022〕1746号)[EB/OL]. 2022. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-11/content_5729354.htm [8] ISWA. Waste-to-energy state-of-the-art-report statistics, 6th edition with revision[M]. International Solid Waste Association, 2013. [9] LICATA A, HARTENSTEIN H U, TERRACCIANO L. Comparison of US EPA and European emission standards for combustion and incineration technologies: Proceedings of the 5th annual North American waste-to-energy conference and exhibition[C]. U. S. : Research Triangle Park, 1997. [10] EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES. Council Directive 89/369/EEC of 8 June 1989 on the prevention of air pollution from new municipal waste incineration plants[S]. 1989. [11] EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES. Proposal for a Council Directive on the incineration of hazardous waste (92/C130/01): Official Journal of the European Communities: [S]. 1992. [12] EUROPEAN UNION. COUNCIL DIRECTIVE 96/61/EC of 24 September 1996 concerning integrated pollution prevention and control: [S]. 1996. [13] EUROPEAN UNION. Directive 2000/76/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 December 2000 on the incineration of waste[S]. 2000. [14] EUROPEAN UNION. Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 on industrial emissions (integrated pollution prevention and control)[S]. 2010. [15] 环境保护部. 污染物在线监控(监测)系统数据传输标准(HJ 212—2017)[S]. 2017. [16] BRINKMANN T, BOTH R, SCALET B M, et al. JRC Reference report on monitoring of emissions to air and water from IED installations[R]. European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, 2018. [17] GEERTINGER A, BLINKSBJERG P, SPOELSTRA H, et al. Quality assurance of automated measuring systems –background for a new european standard: Conference on Emission Monitoring – CEM 2001[C]. Arnhem, Netherlands. 2001. [18] 生态环境部办公厅. 关于加强生活垃圾焚烧电厂自动监控和监管执法工作的通知(环办执法〔2019〕64号) [Z]. 2019 [19] EUROPEAN COMMITTEE FOR STANDARDIZATION. Stationary source emissions - Determination of the mass concentration of PCDDs/PCDFs and dioxin-like PCBs - Part 5: Long-term sampling of PCDDs/PCDFs and PCBs[S]. 2015. [20] REINMANN J. Long-Term Sampling–A Method for Continuous Emission Monitoring of Dioxins/Furans and Mercury[R]. Environnement S. A. , 2012. [21] PSOMOPOULOS C, BOURKA A, THEMELIS N J. Waste-to-energy: A review of the status and benefits in USA[J]. Waste Management, 2009, 29(5): 1718-1724. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2008.11.020 [22] US EPA. Code of Federal Regulations: PART 60—Standards of performance for new stationary sources[S]. 2011. [23] 日本环境省. 一般廃棄物の排出及び処理状況等(令和3年度)について[R], 2023. [24] 日本环境省. 廃棄物処理施設の発注仕様書作成の手引き (標準発注仕様書及びその解説) エネルギー回収推進施設編: ごみ焼却施設(第2版)[M]. 2013. [25] 千葉県環境生活部大気保全課. 事業者のための大気汚染防止法のてびき(平成28年4月版)[S]. 2016. [26] EU TWG. Integrated pollution prevention and control reference document on the best available techniques for waste incineration[R]. European Commission Technical Working Group on Waste Incineration, 2006. [27] 住房和城乡建设部. 生活垃圾焚烧处理工程技术规范 (CJJ 90—2009)[S]. 北京: 中国建筑工业出版社, 2009. [28] NEUWAHL F, CUSANO G, BENAVIDES J G, et al. Best available techniques (BAT) reference document for waste incineration[R]: JRC Science Hub, 2019. [29] HUANG Y, LU J W, XIE Y, et al. Process tracing of PCDD/Fs from economizer to APCDs during solid waste incineration: Re-formation and transformation mechanisms[J]. Waste Management, 2021, 120: 839-847. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2020.11.007 [30] LU J W, XIE Y, XIE B, et al. Buffering effect of the economizer against PCDD/Fs in flue gas from solid waste incineration plants[J]. Waste Management, 2023, 167: 103-112. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2023.05.029 [31] 国家质量监督检验检疫总局, 国家标准化管理委员会. 生活垃圾焚烧炉及余热锅炉 (GB/T—2008)[S]. 北京: 中国标准出版社, 2008: [32] 雷鸣, 谢冰, 海景, 等. 小型简易生活垃圾焚烧炉二噁英类排放特征及呼吸暴露风险评估[J]. 环境污染与防治, 2019, 41(12): 1471-1476. [33] 雷鸣, 谢冰, 海景, 等. 生活垃圾焚烧炉湿法洗涤后烟气二噁英的排放特征[J]. 环境工程, 2019, 37(7): 153-158. [34] 雷鸣, 海景, 程江, 等. 小型生活垃圾热处理炉二恶英和重金属的排放特征[J]. 中国环境科学, 2017, 37(10): 3836-3844. [35] XIE Y, LU J W, XIE B, et al. Systematic evaluation of decentralized thermal treatment of rural solid waste: status, challenges, and perspectives[J]. Resources Conservation & Recycling Advances, 2022, 15(4): 200116. [36] LEI M, HAI J, CHENG J, et al. Variation of toxic pollutants emission during a feeding cycle from an updraft fixed bed gasifier for disposing rural solid waste[J]. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering, 2018, 26: 608-613. doi: 10.1016/j.cjche.2017.07.019 [37] 雷鸣, 海景, 卢加伟, 等. 上吸式固定床气化炉处理生活垃圾时二噁英的形成与迁移[J]. 华南理工大学学报(自然科学版), 2017, 45(11): 139-146. [38] 生态环境部办公厅. 关于加强生态环境监督执法正面清单管理推动差异化执法监管的指导意见(环办执法〔2021〕10号)[EB/OL]. 2021.https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk05/202104/t20210423_830095.html [39] 江苏省生态环境厅, 江苏省市场监督管理局. 固定式燃气轮机大气污染物排放标准 (DB32/ 3967—2021)[S]. 2021. -

下载:

下载: