-

全氟/多氟化合物(per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS)具有热稳定性、化学稳定性、较高的表面活性和疏水疏油等优良特性,自20世纪50年代起被大量生产并广泛应用于多种工业和消费领域[1 − 3]. 传统长链PFAS(全氟碳链长度≥7)包括最具代表性的全氟辛烷磺酸(perfluorooctanesulfonate, PFOS)和全氟辛烷羧酸(perfluorooctanoic acid, PFOA)因具有持久性、生物蓄积性、难降解、生物毒性等特性而备受关注[4 − 8]. PFOA在2005年被美国环保局(US EPA)列为疑似致癌物质[9]. 2006年,US EPA和全球8家主要的氟化学品公司启动了“2010/2015 PFOA管理项目”,旨在2015年前消除PFOA的生产和排放;2013年,PFOA及其铵盐被列入欧盟化学品高风险物质候选清单;2019年,PFOA被列入《斯德哥尔摩公约》“持久性有机污染物”清单附录A[10 − 12]. 随着对PFOA生产和使用的限制,在市场需求的驱动下,开发安全、绿色替代品的研究迅速增加. 多种PFOA替代品(如短链PFAS、氢代多氟羧酸和全氟/多氟烷基醚羧酸)被开发并投入生产和使用[13 − 15]. 由于这些替代品在生产、使用和处理的整个周期中都可以释放到环境中[16],它们在环境中的浓度正呈上升趋势.

新型PFOA替代品——六氟环氧丙烷三聚体羧酸(hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid, HFPO-TA)是一种多醚类全氟烷基醚羧酸(perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids, PFECAs),具有与PFOA相似的结构,是在C—C键之间插入醚键(结构式见表1),替代PFOA在含氟聚合物高性能材料(如聚四氟乙烯和聚偏氟乙烯)生产中作为加工助剂[1, 17]. 2016年,HFPO-TA被中国工信部列入《国家鼓励的有毒有害原料(产品)替代品目录》[21]. HFPO-TA的生产使用在快速增长,其环境污染水平出现上升趋势. 环境中HFPO-TA能通过不同的途径进入生物体并沿食物链传递到高营养级,另外,生物体内长期积累的HFPO-TA会引发多种毒性.

本文从HFPO-TA的生产、用途和环境归趋、环境介质和生物体内的污染现状、生物毒性以及降解等方面进行综述,以期为进一步研究HFPO-TA的环境行为、生物富集与转化以及毒性效应机制提供参考依据,并对目前仍存在的问题和未来的关注方向进行总结和展望.

-

HFPO-TA是由2个六氟环氧丙烷(hexafluoropropylene oxide, HFPO)聚合脱氟形成中间化合物六氟环氧丙烷二聚体(化合物1),六氟环氧丙烷二聚体再与HFPO聚合脱氟生成中间化合物六氟环氧丙烷三聚体(化合物2),然后,六氟环氧丙烷三聚体经过与NaOH、HCl作用,最终生成HFPO-TA,具体的合成路径如下公式(1—4)所示[17, 22]. HFPO-TA的表面张力和临界胶束浓度分别是19.3 mN·m−1 和4.10 g·L-1[22 − 23],说明HFPO-TA具有非常好的表面活性. 目前,HFPO-TA已在我国多地生产使用,山东华夏神州新材料有限公司在2008年上半年自主研发了HFPO-TA作为PFOA替代品,在我国以T-5商标生产,采用替代品T-5生产的含氟聚合物与用PFOA生产的树脂相比具有几近相同的物理及加工性能,并且添加量降低为0.20%[24 − 25]. 上海三爱富公司开发的新型含氟表面活性剂FS(不同相对分子质量的全氟聚醚羧酸盐(包括HFPO-TA盐)与含氟可聚合季铵盐型阳离子表面活性剂复配物)替代PFOA广泛用在聚四氟乙烯和氟橡胶等含氟生产过程中的乳化剂[26].

-

HFPO-TA具有与PFOA相似的热稳定性、化学稳定性、较高的表面活性及疏水疏油等优良特性[1, 11, 17],主要被用在含氟聚合物高性能材料(比如聚四氟乙烯和聚偏氟乙烯)生产中,替代PFOA作为加工助剂,同时也是合成其他含氟产品(包括表面活性剂、防油剂、离子液体和工业添加剂)的重要组成部分[17]. 虽然包括HFPO-TA在内的低分子量PFECAs及其盐类在美国未获得授权用于食品包装材料,但已被广泛用作食品包装材料生产过程中的加工助剂[27]. 另一方面,由于结构中氧原子的插入和C—O键的柔韧性,PFECAs除了具有与传统PFAS相似优良特性外,还具有良好的粘滞特性,这种沿链的柔韧性可防止结晶,从而使其具有在较大温度范围内保持液态的能力[27 − 28],因此,HFPO-TA也是高温、高压、高摩擦等苛刻条件下(如航空航天应用)用作润滑剂的理想选择[29].

-

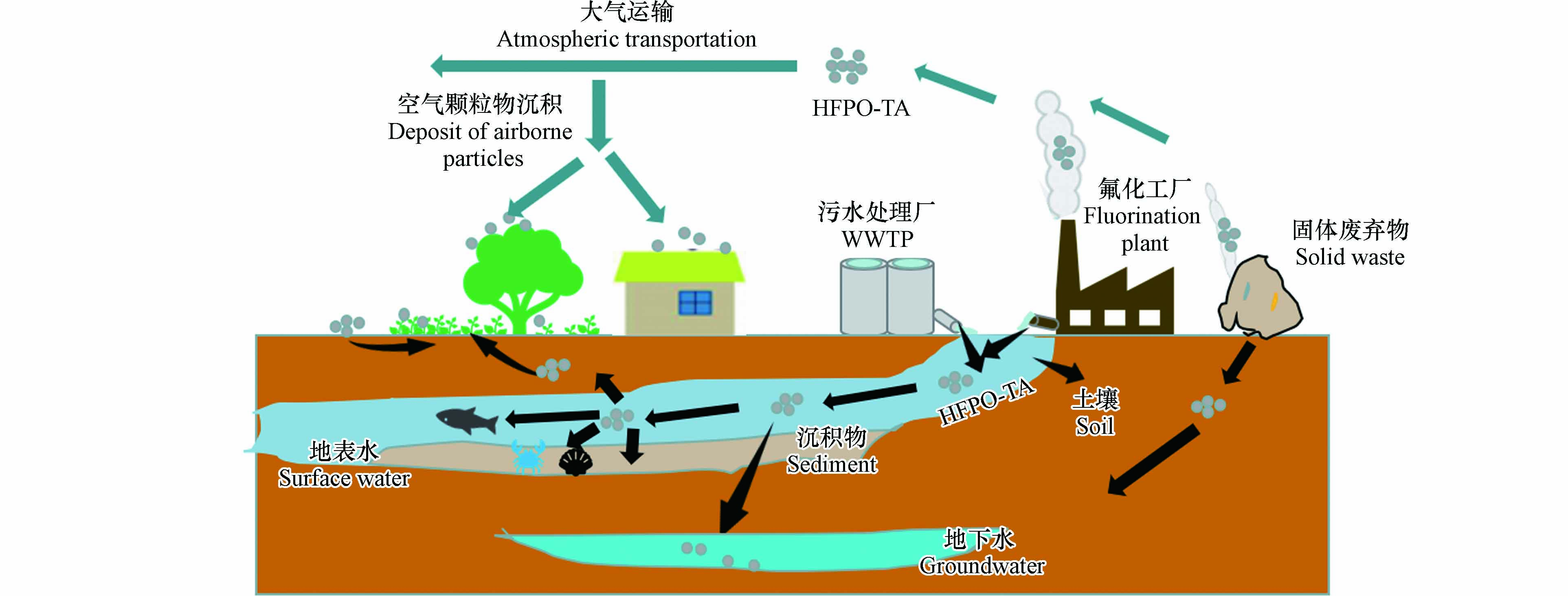

根据HFPO-TA的生产和用途,环境中HFPO-TA主要来源于氟化工厂(fluorochemical industrial park,FIP)、污水处理厂(wastewater treatment plant, WWTP)和固体废弃物(图1). 这些污染源也使环境中HFPO-TA的浓度具有明显的区域化效应,即靠近这些点源的介质中HFPO-TA浓度较高,随着距离的增加HFPO-TA浓度降低[25, 30].

HFPO-TA随FIP和WWTP的出水进入地表水,然后通过水体多界面分配进入颗粒相最终在沉积物中富集[31 − 32],并能迁移到地下水[30, 33];水体中的HFPO-TA能通过摄食和呼吸等方式进入水生生物进而在食物链循环[10, 17]. 另外,表层水和固体废弃物中HFPO-TA能通过灌溉和渗滤液迁移到土壤中并被植物通过根部吸收经木质部转移到地上部分并在果实中富集[25]. HFPO-TA主要通过FIP和固体废弃物的废气进入大气并分配到颗粒相中,通过大气运输进行长距离迁移,随后通过干沉降进入地表(如植物叶片、土壤等)[25, 34]. 由此可见,通过这些污染源进入环境中的HFPO-TA会随大气和水进行长距离运输,从而使HFPO-TA在大气、土壤、水体和生物圈内迁移(图1),并成为人体HFPO-TA的主要来源. 因此,HFPO-TA在环境多种介质(表层水、地下水、悬浮物沉积物、土壤、灰尘)、植物、水生生物和人体中广泛检出.

-

HFPO-TA作为PFOA替代品已使用多年并在全球范围多介质中广泛检出(见表2). HFPO-TA在包括中国、美国、德国、英国、荷兰、瑞典、韩国等多国19条河流中检出,在国外河流中,HFPO-TA在美国Delaware River的浓度较其他河流浓度高,最高浓度达4.33 ng·L−1,而在国内不同地区河流中的浓度差异较大,其中太湖最高浓度达34.8 ng·L−1,接近该地区PFOA浓度(3.15—44.5 ng·L−1)[35],说明HFPO-TA正在被广泛生产和使用并成为全球性污染物. 工业排放作为环境中HFPO-TA的主要来源,在氟化工业区地表水中发现较高浓度的HFPO-TA. FIP出水通过支流汇入小清河后,该河流下游HFPO-TA浓度高达68500 ng·L−1,约是上游水体浓度的120—1600倍,据估计该河流HFPO-TA的排放量约4.6 t·a−1,占PFAS总排放量的22% [17]. 目前WWTP常规处理工艺并不能有效去除HFPO-TA,在江苏常熟氟工业区WWTP的出水检出高浓度的HFPO-TA(浓度中值达360 ng·L−1),在该工业园区周边的排水渠道也检出了HFPO-TA,平均浓度为3.31 ng·L-1[36]. 此外,在望虞河(1.50 ng·L−1)[36]、海河(0.004—3.83 ng·L−1)[37]、南黄海(0.92—6.68 ng·L−1)[31]和鄱阳湖(0.95 ng·L−1)[32]水中也检出了低浓度的HFPO-TA. 由此可见,表层水中HFPO-TA具有明显的区域化效应,即FIP周边的表层水中HFPO-TA浓度高于其他地区. 除此之外,HFPO-TA的浓度变化还具时间效应,Yao等[36]分析了2016—2021年间太湖表层水HFPO-TA的浓度变化,结果发现HFPO-TA从0.38 ng·L−1(2016年)增加到1.72 ng·L−1(2021年),说明HFPO-TA作为PFOA替代物在过去5年的生产和使用是不断增加的. 此外,HFPO-TA在常州段的长江和德胜河的浓度与季节存在一定的关系,在丰水期的浓度(0.39 ng·L−1和0.32 ng·L−1)高于枯水期(0.07 ng·L−1和0.08 ng·L−1)[38]. HFPO-TA在河流中能分配到悬浮物和沉积物中并在沉积物中富集[31],其在鄱阳湖悬浮物和沉积物中的平均浓度分别为410 pg·L−1和200 pg·g−1 dw(干重),均高于PFOA(99 pg·L−1和31 pg·g−1 dw(干重))[32],在南黄海沉积物(7.57—113 pg·g−1 dw(干重))中的浓度却低于PFOA(71.7—1826 pg·g−1 dw(干重))[31]. 虽然HFPO-TA在南黄海沉积物中的浓度低于PFOA,但其在沉积物—孔隙水分配系大于PFOA[31],说明HFPO-TA比PFOA更倾向于分配到沉积物中. 污染物在水体中的分配行为受多种因素影响,因此,HFPO-TA在水体多界面间分配行为和影响因素也是今后值得探究的一个方向.

-

HFPO-TA能随水体进行长距离运输并迁移到地下水[30, 33, 41]. Zhou等[33]首次在黄土高原地下水中检测到HFPO-TA,检出率高达100%,平均浓度为0.31 ng·L−1. 在常熟FIP附近地下水和山东桓台FIP附近地下水中HFPO-TA的浓度分别为0.07—38.0 ng·L−1和3.89—462 ng·L-1[30, 39],分别比黄土高原地下水HFPO-TA浓度高约10倍和100倍,说明工业污水的排放是地下水HFPO-TA污染的重要来源. 在我国许多地区由于气候干旱,缺水严重,地下水是饮用水和农业灌溉的来源[42],一些欠发达地区,地下水通常不经处理直接作为饮用水,因此,地下水中HFPO-TA污染会对当地居民健康构成潜在风险.

饮用水主要来源于地下水而且是人类暴露PFAS的重要途径[43 − 45],然而常规的饮用水处理方法并不能有效去除PFAS污染[46 − 49]. Feng等[25]在山东桓台FIP附近村庄收集的自来水样品中检测到HFPO-TA,最高浓度达81.2 ng·L−1,比该地区地下水(最高浓度462 ng·L−1)浓度仅低6倍左右,虽然经过前期处理但并不能有效去除HFPO-TA. Qu等[38]在常州3个饮用水公共供水系统中检测到HFPO-TA,其平均浓度分别为n.d. —0.21 ng·L−1(冬季)和0.44—0.52 ng·L−1(夏季),与饮用水处理厂出水浓度相当,说明传统的处理工艺对HFPO-TA去除效果不佳,但在处理工艺中添加颗粒活性炭则能有效的去除HFPO-TA且去除率达100%.

-

空气中的气溶胶和颗粒物是PFAS在大气中迁移的重要载体[34, 50 − 51]. Feng等[25, 39]在山东桓台FIP附近村庄的室内外灰尘中检测到高浓度的HFPO-TA,其在室内灰尘中的浓度(4014 ng·g−1)远远高于PFOA(421 ng·g−1)和C4—C7全氟烷基羧酸(perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids, PFCAs)(1320 ng·g−1),HFPO-TA是室外灰尘中的主要PFAS,占∑18PFAS 总量的 61%,其浓度(189—4250 ng·g−1)也显著高于PFOA(24.6—459 ng·g−1),说明与PFOA和短链PFCAs相比,HFPO-TA更易分配在颗粒相中,从而加速其在灰尘中的沉积,另外,该研究也表明HFPO-TA在该FIP周围通过大气传输的途径已经发生. 空气中的HFPO-TA能通过干沉降进入到土壤中,土壤对HFPO-TA具有较强的富集能力,同时也是HFPO-TA重要的“汇”. 土壤中HFPO-TA的来源通常包括固废中渗滤液的迁移和大气中HFPO-TA的颗粒物沉降[34, 52]. Xu等[40]在杭州生活垃圾填埋场附近(< 5 km)的土壤中检出HFPO-TA,尽管浓度较低(低于定量限0.30 ng·g−1),但检出率高达14%. Liu等[30, 53]在江苏常熟FIP(东部20 km以内)附近水稻和小麦轮作的农田里也发现了低浓度的HFPO-TA(0.02 ng·g−1),土壤中的HFPO-TA会被农作物的根系吸收并在植物体内富集,最终威胁着人类健康. Feng等[39]发现HFPO-TA是桓台县氟工厂附近土壤中主要PFAS,占∑18PFAS总量的71%,其浓度(53.7—2910 ng·g−1)显著高于PFOA(22.8—185 ng·g−1),而且在距离该FIP上风向 > 10 km的一个采样区域土壤中HFPO-TA(61.7 ng·g−1)的浓度高于PFOA(48.6 ng·g−1),说明FIP附近HFPO-TA的主要来源是大气传输而且HFPO-TA通过大气迁移沉积到土壤中的速度比PFOA快.

-

植物作为食物链初级生产者,在生态系统中具有不可或缺的重要性,目前已在植物体内检出HFPO-TA的存在,其来源主要是大气和土壤[25, 54]. Feng等[25]在桓台县FIP附近村庄的谷物(小麦和玉米)和蔬菜中检出了HFPO-TA,其在蔬菜中的浓度(45.1 ng·g−1 dw(干重))显著高于小麦(3.71 ng·g−1 dw(干重))和玉米(0.68 ng·g−1 dw(干重)),由于大气的沉降作用,HFPO-TA在绿叶蔬菜中HFPO-TA浓度(111 ng·g−1 dw(干重))显著高于蔬菜的平均浓度(45.1 ng·g−1 dw(干重))(表3). 此外,HFPO-TA在水生生物体内也广泛检出,环境中HFPO-TA能通过摄食、呼吸、接触等多种方式迁移到生物体内,从而进入食物链循环. 山东FIP附近小清河采集的野生鲤鱼体内HFPO-TA的检出率为100%, HFPO-TA在鲤鱼血中浓度高达1510 ng·mL−1,血中生物浓缩因子(bioaccumulation concentration factor,BCF)lgBCF血(2.18)显著高于PFOA(1.93),在肝和肉中浓度中值分别为587 ng·g−1 ww(湿重)和118 ng·g−1 ww(湿重)高于PFOA(449 ng·g−1 ww(湿重)和73.6 ng·g−1 ww(湿重))[17],说明HFPO-TA在鱼体内的积累潜能强于PFOA. HFPO-TA不仅能在水生生物体内富集,还能沿食物链传递. Li等[10]调查了小清河河口不同营养级的生物体内HFPO-TA的含量,HFPO-TA在浮游生物、双壳类、甲壳类、腹足类和鱼类的平均浓度分别为34.6、9.14、72.2、3.16、67.4 ng·g−1 dw(干重),并且检出率为100%,HFPO-TA的营养级放大因子(trophic magnification factors, TMF = 5.25)大于1,说明HFPO-TA 能被传递到高营养级并呈放大效应. 在山东桓台(距FIP约10—20 km)采集的雄黑斑蛙体内也检出了HFPO-TA,它在黑斑蛙不同组织中浓度差异较大,其在肾脏、性腺、肝脏、心脏的浓度最大,说明这些器官可能是HFPO-TA的主要靶器官,另外还发现在所有组织中HFPO-TA的浓度均高于PFOA,并且在全蛙体中的生物富集系数(bioaccumulation factor, BAF )(0.76 L·kg−1)大于PFOA(0.37 L·kg−1)[18],表明HFPO-TA不仅能在水生生物体内富集,在两栖动物体内的也具有较强的积累潜能. 此外,在桓台县FIP附近村庄的家养鸡蛋中也发现较高浓度的HFPO-TA,其浓度为611 ng·g−1 dw(干重)显著高于PFOA(466 ng·g−1 dw(干重))[25]. 以上结果显示HFPO-TA在动植物体内具有比PFOA更高的积累潜能,主要与化学结构和理化性质有关,一方面,HFPO-TA结构中含有醚氧和支链,其碳链长度和分子尺寸大于PFOA,研究表明当碳原子个数小于14时,PFAS的富集能力与碳链长度呈正相关[57 − 58],另一方面, HFPO-TA具有较高的疏水和亲蛋白性,其lg Kow和lg Kpw(5.55和3.85)均大于PFOA(4.81和3.43)(表1),根据PFAS的BCF与lg Kow和lg Kpw呈正相关关系,HFPO-TA具有较强的富集能力[21, 57 − 60].

-

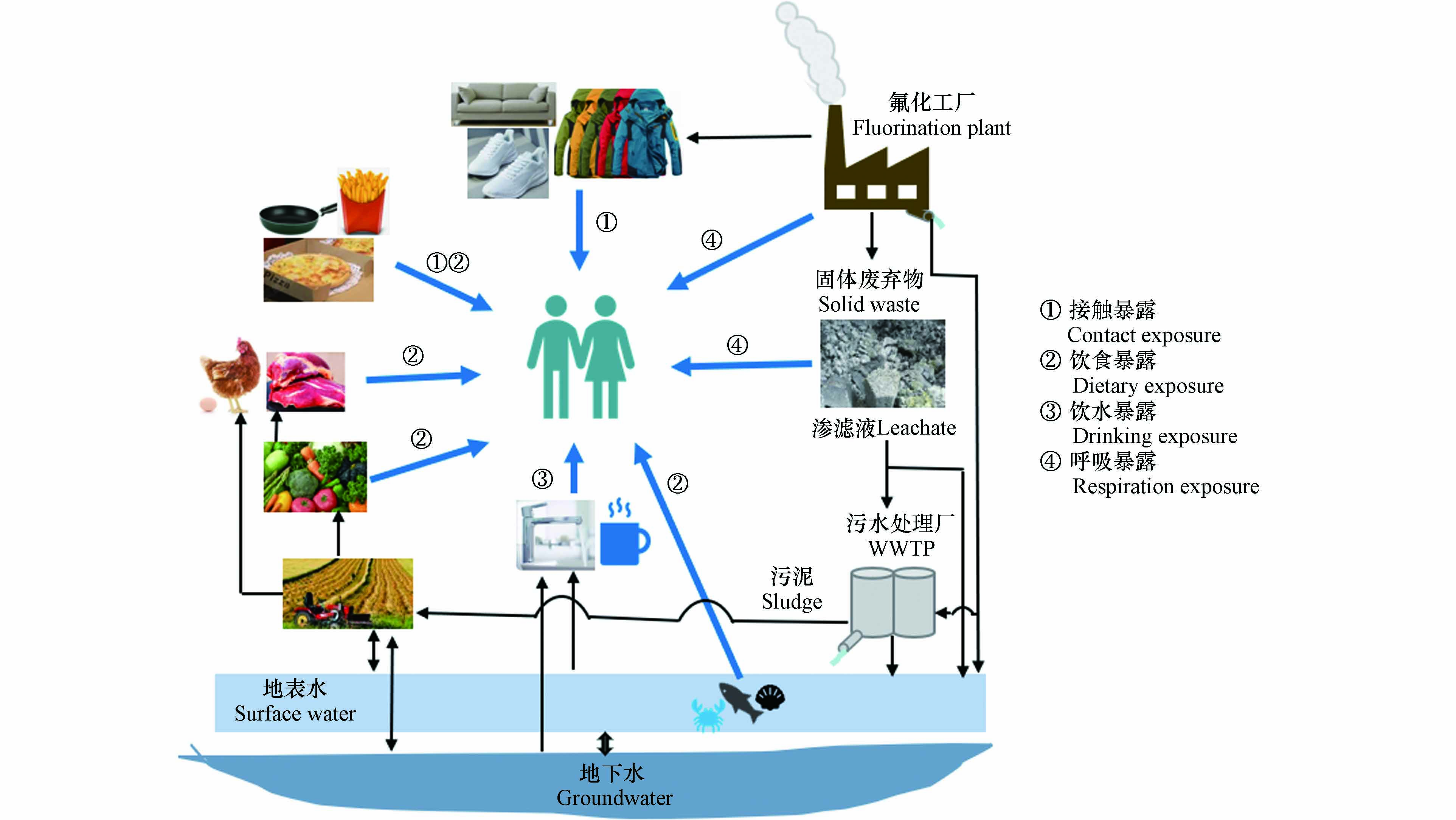

HFPO-TA主要通过呼吸暴露、饮食暴露、饮用水暴露和皮肤接触暴露等方式进入到人体中(图2),其中饮食暴露是人体内HFPO-TA的主要暴露途径.

Feng等[25]计算了山东桓台县FIP周边居民HFPO-TA在饮食、灰尘和饮用水途径的每日摄入量(estimated daily intake,EDIs)并评估了其外暴露风险,HFPO-TA和PFOA在这3种途径的总EDIs分别是231 ng·kg−1·d−1·bw和457 ng·kg−1·d−1·bw,其中饮食摄入对总EDIs的贡献量最大(≥ 98%),虽然目前还未有HFPO-TA的每日可耐受摄入量(tolerable daily intake,TDI)建议值,但其总EDIs接近PFOA(TDI = 12.5 ng·kg−1·d−1·bw)[54],因此,HFPO-TA的暴露尤其是饮食暴露使居民面临潜在健康风险. 环境中的HFPO-TA进入人体后,能在人体内富集并已经在血液、尿液和不同组织中检出HFPO-TA. Pan等[17]2016年调查了桓台县FIP附近居民(n = 48)血清中PFAS的暴露水平,发现HFPO-TA的检出率> 98%,浓度中值为2.93 ng·mL−1. Yao等[56]在2019—2020年再次采集并分析了该地区居民血清(n = 977)中PFAS浓度水平并发现血清中HFPO-TA的浓度与年龄有关,HFPO-TA在2—18岁、19—40岁、41—60岁和 > 60岁年龄组的中值浓度分别为1.34、1.34、2.29、2.63 ng·mL−1,不同年龄组体内HFPO-TA富集含量的差异可能是由于不同年龄段的代谢能力不同,但是,由于HFPO-TA可经胎盘传递、母乳传递、手口接触等行为进入幼儿体内以及不同代谢机制的存在,因此导致0—1岁年龄组幼儿体内HFPO-TA的浓度(中值1.70 ng·mL−1)明显高于青少年和成人(2—40岁)组. 因此,婴幼儿体内高浓度HFPO-TA对其生长发育造成的影响更值得关注. 此外,在桓台县附近居民的尿液和头发中也检出了HFPO-TA,其浓度分别为22.7 ng·mL−1和14.7 ng·g−1,HFPO-TA在尿液中的浓度高于PFOA(7.30 ng·mL−1),这意味着HFPO-TA在人体中的代谢速度比PFOA更快[25]. 另外,在非FIP影响的地区的人体内也发现了HFPO-TA,Kang等[55]在北京大学人民医院收集的28位寻求体外受精健康女性的卵泡液中发现HFPO-TA的检出率为36%,浓度范围为n.d. —0.36 ng·mL−1. 由此可见,HFPO-TA能通过不同的途径进入人体,若人们长期暴露在HFPO-TA中,其风险则不容忽视.

-

环境中HFPO-TA通过多种途径进入生物体后能在其中蓄积并产生多种潜在的毒性. 目前已经发现HFPO-TA具有细胞毒性、肝脏毒性、内分泌干扰毒性、生殖毒性和潜在的致癌风险[11, 61 − 64]. Sheng等[65]发现HFPO-TA在低浓度时就能促进细胞增殖,其(IC50 = 3.42 × 10−4 mol·L−1)对肝细胞的毒性大于PFOA(IC50 = 7.77 × 10−4 mol·L−1),然而,HFPO-TA引起细胞毒性的作用机制与PFOA不同,由于其结构中氧原子的插入,使分子出现结构扭转,导致其以独特的结合方式与人体肝脏脂肪酸结合蛋白(human liver fatty acid binding protein, hL-FABP)结合,最终HFPO-TA与hL-FABP的结合能(−34.9 kJ·mol−1)强于PFOA(−30.7 kJ·mol−1),导致更严重的肝细胞毒性. 肝脏是PFAS作用的主要靶器官,因此HFPO-TA的肝脏毒性也成为科学家关注的热点[66 − 69]. 小鼠暴露HFPO-TA后,其肝重和相对肝重均显著增加,HFPO-TA能诱导比PFOA更严重的肝脏损伤(如肝肿大、细胞核溶解、细胞坏死、细胞质空泡化和丙氨酸转氨酶活性增加)并通过激活过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体(peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, PPAR)通路诱导脂质代谢紊乱[11];此外,HFPO-TA诱导小鼠肝细胞受损后还会引发肝脏炎症,高浓度的HFPO-TA会导致线粒体数量、相对线粒体DNA含量(mtDNA)和由mtDNA编码的线粒体基因的mRNA水平增加,并改变与线粒体功能相关的代谢途径[70]. 体外实验进一步验证了HFPO-TA的肝脏毒性,小鼠3D原发性肝脏球体暴露HFPO-TA后,其胆固醇代谢、胆汁酸代谢和炎症发生了显著改变且HFPO-TA比PFOA的肝脏毒性更严重[61]. HFPO-TA降低了人胚胎干细胞存活率并呈剂量依赖性,HFPO-TA能导致细胞内ROS积累、降低线粒体膜电位,在高浓度组凋亡/坏死细胞增多,即使非细胞毒性浓度下,HFPO-TA仍能通过降低细胞糖原储存能力和解除对特定功能基因的调控损害肝细胞功能[71]. Li等[72]通过比较HFPO-TA和PFOA与人和小鼠PPARγ的结合能力、受体激活活性和细胞脂肪生成活性的影响,发现HFPO-TA与PPARγ的结合能比PFOA高4.8—7.5倍,对HEK293细胞PPARγ信号通路的激活能力、促进小鼠和人前脂肪细胞的脂肪形成分化和脂质积累的效力均强于PFOA.

除了肝脏毒性,Xin等[62]发现HFPO-TA具有内分泌干扰毒性,他们发现HFPO-TA显著改变了斑马鱼性类固醇激素和卵黄原蛋白水平,而且HFPO-TA与雌激素受体配体(estrogen receptor ligand binding domains, ER-LBDs)的结合能(ERα:−115 kJ·mol−1,ERβ:−122 kJ·mol−1)高于PFOA(ERα:−107 kJ·mol−1,ERβ:−113 kJ·mol−1),体内和体外实验结果一致表明HFPO-TA比PFOA具有更高的雌激素效应. 另外,研究还发现HFPO-TA对微生物具有一定的毒性,HFPO-TA能导致小鼠盲肠菌群失衡和盲肠菌群多样性的改变,并且能改变不饱和脂肪酸合成、脂肪酸代谢、乙醛酸和二羧酸代谢、半乳糖代谢等代谢途径[73]. HFPO-TA还影响土壤微生物的丰度、群落结构和功能,HFPO-TA对古菌和细菌的丰度先降低后增加,在整个暴露过程中,增加了氨氧化古菌的丰度却抑制了氨氧化细菌生长,对潜在消化率的影响也是先促进后抑制[74]. 与PFOA相似,HFPO-TA也具有生殖毒性,Peng等[63] 通过体内外实验发现HFPO-TA通过激活p38 MAPK磷酸化促进TJ闭合蛋白降解从而上调MMP-9s表达,最终破坏血-睾屏障的通透性,并且HFPO-TA对血-睾屏障通透性的干扰强于PFOA. 值得注意的是HFPO-TA具有潜在的致癌风险,小鼠通过灌胃暴露HFPO-TA 28天后,虽然在小鼠肝脏中未检测到肿瘤,但转录组和蛋白组分析发现参与化学致癌途径和肿瘤生成的基因和蛋白表达增加,说明HFPO-TA具有很强的致癌潜力[11]. Pan等[64]以人骨髓充质干细胞为体外模型,评估了HFPO-TA潜在的致癌风险,结果发现HFPO-TA增强了细胞增殖并抑制了干细胞多能性,改变了肿瘤相关基因和蛋白表达,表明与癌变相关的细胞周期调控异常和多能性损伤,而且发现HFPO-TA引发的这种不良影响的作用模式可能与PFOA相似,该研究为HFPO-TA的健康风险提供了人类相关证据. 综上所述,HFPO-TA与PFOA相似的化学结构使它们具有相似的生物毒性,然而,由于结构中氧原子的存在和理化性质的不同,HFPO-TA的生物毒性强于PFOA,关于HFPO-TA独特的毒性机制和与蛋白质的结合方式以及与PFOA毒性机制的差异,值得进步一研究.

-

HFPO-TA独特的结构(醚键)为化学反应(氧化反应和还原反应)提供作用位点,在氧化性物质(UV/过硫酸盐)和还原性物质(水合电子)作用下,发生氧桥断裂,生成较短碳链PFAS. Bao等[75]发现HFPO-TA在UV/过硫酸盐系统中240 min降解60%,在SO4-·作用下被氧化成六氟环氧丙烷二聚体羧酸(hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid, HFPO-DA),由于HFPO-DA具有较强的抗氧化性从而导致HFPO-DA的大量产生和积累,给环境中HFPO-DA污染带来风险,后续研究探究了HFPO-TA在UV/亚硫酸盐系统中的降解反应,HFPO-TA在2 h就可以完全降解,8 h内的脱氟率达76%,在水合电子(eaq-)作用下生成中间产物HFPO-DA、氟烷基丙酸(perfluoropropionic acid, PFA)、三氟乙酸(trifluoroacetate, TFA),最终转化成CO2、F-和HCOO-等离子碎片,基于此,将UV/亚硫酸盐与纳滤技术耦合,HFPO-TA在60 min内达到99.7%的去除率并在120 min后回收全部的氟化物,证实了UV/亚硫酸盐还原是饮用水深度处理中纳米过滤的互补技术. Bentel等[76] 探讨了HFPO-TA在紫外线产生的eaq-作用下的降解机制,48 h HFPO-TA的脱氟率为36.5%,结构中醚氧使HFPO-TA具有独特的降解行为,其降解路径主要有3种:①C—F键断裂和C—H键形成(H/F交换),②脱羧—羟基化—HF消除—水解,③C—O键断裂,结构中醚氧增加了相邻—CF2—部位上C—F键的解离能,从而减少了H/F交换形成的抗还原脱氟的多氟产物,另外,C—O键的断裂会产生不稳定的全氟醇,从而促进短氟烷基部分的深度脱氟,由于结构中含有—CF3支链,在叔碳上具有更高的H/F交换趋势,因此脱氟率降低,该研究为改进设计和有效降解含氟化合物提供了依据. Li等[77]研究了HFPO-TA水溶液在紫外光照射下的转化,发现在紫外光照射72 h后,降解率和脱氟率分别是75%和25%,在降解过程中水分解产生的还原活性物质(水合电子和活性氢原子)起主要作用. Chen等[78]自主研发了一种自组装胶束系统,在环境条件下通过使用3种羟基苯乙酸(hydroxyphenylacetic acids, 2-HPA、3-HPA和4-HPA)作为水合电子前体,在紫外线照射下降解HFPO-TA,3种胶束系统均能降解HFPO-TA,其中2-HPA胶束系统的高分解和脱氟效率以及抗干扰能力为处理PFAS污染废水提供前景技术. 综上所述,HFPO-TA在化学反应(氧化和还原)中能够发生降解,其降解路径为HFPO-TA → HFPO-DA →PFA→TFA. 另一方面,HFPO-TA具有与PFOA相似的结构,如均具有全氟化的碳链,因此,HFPO-TA具有与PFOA相似的持久性,然而,HFPO-TA结构中插入的两个醚氧以及周期性的—CF3支链会改变HFPO-TA结构的稳定性,但是目前尚未有文献报道HFPO-TA在自然环境及生物体内发生转化,因此探究HFPO-TA在生物体内的毒代动力学和生物转化是今后亟需关注的方向.

-

作为PFOA新型替代品,HFPO-TA在环境介质、动物和人体中广泛检出并已成为全球性污染物. FIP的工业生产过程是环境中HFPO-TA 主要来源,在受FIP影响的地区,HFPO-TA在一些介质中的浓度接近甚至高于PFOA. HFPO-TA能通过多种途径进入植物、动物和人体内并在其中蓄积,并能引发细胞毒性、肝脏毒性、内分泌干扰毒性、生殖毒性以及潜在的致癌风险,由于独特的结构和理化性质,HFPO-TA的生物积累潜能和生物毒性均强于PFOA. HFPO-TA结构中的醚键为化学反应提供作用位点,发生氧桥断裂被降解. 未来亟需在以下方面开展深入研究:(1)环境监测数据显示HFPO-TA易分布在悬浮颗粒物和沉积物中,但其分配行为和影响因素还不清楚,需要开展研究系统探究HFPO-TA化学结构和理化性质对其在水体多界面(水、固体颗粒物、气溶胶)间分配行为的影响机制;(2)现有研究主要集中在高浓度和短期暴露毒性,然而污染物对不同物种和不同性别的毒性效应不同,因此需要进一步探究HFPO-TA长期低浓度暴露的毒性效应,探明性别和物种差异;(3)HFPO-TA结构中的醚氧改变了其结构稳定性,然而目前关于HFPO-TA在生物体内是否发生转化还未见报道,生物体中含有丰富的酶,C—O键是否会在生物酶的催化下发生断裂需要进一步探究并识别相I和相II代谢产物.

六氟环氧丙烷三聚体羧酸(HFPO-TA)污染现状和生物毒性研究进展

A review of contamination status and and biotoxicity of hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid (HFPO-TA)

-

摘要: 全氟/多氟化合物(per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances,PFAS)是一类具有优良表面活性和稳定性的有机化合物,广泛应用于工业和消费领域,全氟辛烷羧酸(perfluorooctanoic acid,PFOA)是具有代表性的一类PFAS. 由于具有持久性、生物蓄积性、长距离迁移和生物毒性,PFOA已被限制生产和使用. 六氟环氧丙烷三聚体羧酸(hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid,HFPO-TA)是一类新型的PFOA替代品. HFPO-TA在全球范围内的环境介质中广泛存在,在一些介质中的浓度接近甚至高于PFOA. HFPO-TA能在生物体内蓄积并可产生生物毒性效应,由于其独特的化学结构和理化性质,HFPO-TA的生物积累潜能和生物毒性强于PFOA. 本文从HFPO-TA的生产、用途、环境归趋、环境介质和生物体内的污染现状、生物毒性和降解进行综述,并对未来研究趋势和发展方向进行展望,为研究HFPO-TA在生物体内富集与转化机制和毒理学评价提供参考依据.

-

关键词:

- 六氟环氧丙烷三聚体羧酸 /

- 多介质分布 /

- 生物富集 /

- 生物毒性 /

- 降解.

Abstract: Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of organic compounds with excellent surface activity and stability, which are widely used in industrial and consumer fields. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) is a representative class of PFAS. Duo to its persistence, bioaccumulation, long-distance migration and biological toxicity, PFOA has been restricted in production and use. Hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid (HFPO-TA) is a novel alternative to PFOA. HFPO-TA is widely distributed in environmental around the word, and its concentration in some media is close to or even higher than PFOA. HFPO-TA can accumulate in organisms and lead to biological toxicity. Due to its unique chemical structure and physical and chemical properties, HFPO-TA has stronger bioaccumulation potential and biological toxicity than PFOA. In this paper, the production, use, environmental fate, the pollution status in environmental medium and organisms, biotoxicity and degradation of HFPO-TA are reviewed, and the future research trend and development direction are prospected, providing reference basis for the study of enrichment and transformation mechanism of HFPO-TA in organisms and toxicological evaluation. -

近年来,随着城市生态环境的建设,我国城市点源污染控制效果良好,但合流制管道溢流(combined sewer overflows,CSOs)作为城市典型的非点源污染的危害日益凸显出来[1]。由于历史等原因,合流制排水系统仍存在于国内外大多数老城区中,承载着城市生活污水和雨水收集、输送、排放等任务[2],但在降雨时,存在着溢流污染问题。溢流污水中含有各种病原微生物、氮磷等营养元素、各种病菌及有毒有害物质[3],会在降雨期间通过侵蚀或冲刷进行迁移,对城市水体造成污染[4]。合流制溢流污染已经成为城市水环境污染、生态系统失衡的重要原因[5],对城市生态环境产生了严重的威胁,因此,溢流污染的治理已十分紧迫[6−7]。

为治理污水溢流所造成的污染,需从源头对管道进行改造,早在1964年美国就开始了对合流制管道溢流污染控制的研究,经过几十年的发展,现已形成较为成熟的理论和技术[8]。合流制管道溢流污染控制核心包含两方面,一方面是排水系统改造,如扩容管径、铺设新的输水管道、增加排水泵站等来提高截污效率,减少溢流量;另一方面是通过绿色措施,如雨水花园、生物滞留系统、绿色道路等从源头上降低排水管道负荷[9]。我国对合流制溢流污染研究起步较晚,一直没有予以足够的重视,以至于没有形成相关的法规与技术指导标准。现阶段国内一些城市开始逐步重视了CSOs污染问题,并开展了相关研究及相应治理措施[10]。

为了响应国家《水污染防治行动计划》的明确要求,武汉市对巡司河制定了黑臭水体整治方案。本研究基于巡司河片区CSOs治理项目,以武汉市巡司河片区为研究对象,针对溢流污染问题,尝试借鉴工程实例并运用暴雨洪水管理模型(storm water management model,SWMM)软件建立该地区管网水力学模型。通过对工程措施的模拟,进行了污染物截流效率及年污染物溢流量的模拟评估,量化评价工程措施的运行效果,由此确定合理的治理方案,解决了合流制管网污水溢流所导致的城市内涝和城市内河黑臭问题。

1. 模型的构建

1.1 研究区域概况

武汉市巡司河片区位于武汉市武昌区南部,地处亚热带大陆季风性(湿润)气候区,年降雨量1 150~1 450 mm,每年4—9月是主要雨期,降水量占全年70%左右。汇水区域包括:武泰闸合流区子系统、晒湖合流区子系统、武船子系统和沿途合流子系统,总面积达到11.5 km2。该地区的总体地势较为平坦,典型下垫面包括道路路面、屋面、停车场、绿地等,路面根据道路面层可以分为水泥路面、沥青路面;屋面根据屋顶材质可以分为油毡屋面、水泥屋面、瓦屋面;绿地根据植被种类以少部分草坪为主。

1.2 模型概化及参数设定

SWMM是由美国国家环境保护局(United States Environmental Protection Agency)于20世纪70年研制的城市暴雨管理计算机模型[11]。该模型可用模拟完整的城市降雨径流,包括地表径流和排水管网中水流、地表污染物的积聚与冲刷、合流污水溢流过程等,因此,对于合流制溢流污染特征分析和合流制排水管道的规划设计来说是一个行之有效的工具。

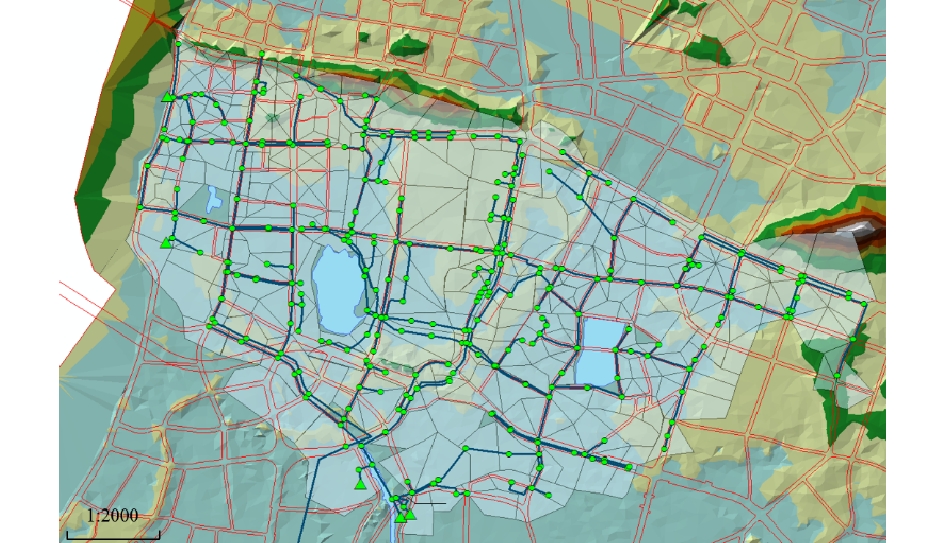

汇水区域内地形数据主要采用1:2 000地形图,根据巡司河地区实际道路的走向、街区的分布与地表径流的流向,将模拟区域人工划分为288个汇水子区域,面积从1.4 ha到7.2 ha不等,根据地形图,计算各汇水子区域的平均坡度为1%,汇水区域概化宽度为52.66 m。假设整个区域上的降雨是均匀的,每个子小区雨水就近汇入管网节点,再根据管网资料以及上述汇水区域的划分结果,将管道信息录入模型,排水管道的主干管均为钢筋混凝土管道。由此得到的管道概化结果如图1所示:在288个汇水子区域里,排水管网概化为516个节点和515段管道,124个排口,5个电排站。

水力模型参数有透水地面初始积洼深度、不透水地面初始积洼深度、透水地面曼宁系数等,此类参数需要依据实际情况并参照手册提供的参数[12]确定。其中入渗模型选择霍顿模型,最大入渗率、最小入渗率、入渗衰减系数分别为76 mm·h−1、3.3 mm·h−1、2 h−1[13];不透水地面初始积洼深度为1.5 mm;不透水地面粗糙系数为0.015;透水地面初始积洼深度为5 mm;透水地面粗糙系数为0.02;排水干管的材质为钢筋混凝土,通过查询SWMM用户手册,再参考国内的研究模拟成果,拟定管道曼宁系数为0.01;无洼地蓄水的不透水地表百分数为25%;汇流模型采用非线性水库模型;水力模型选择动力波。

1.3 设计雨型及雨量

本研究采用武汉市暴雨强度公式[14]进行暴雨强度计算,如式(1)所示。

q=885(1+1.58lg(P+0.06))(t+6.37)0.604 (1) 式中:q为设计暴雨强度,L·(s·hm2)−1;P为重现期,年;t为降雨历时,min。

设计雨型采用芝加哥雨型[15],降雨重现期分别设为3、5、10年,降雨历时为2 h,退水时间为2 h,模拟总历时为4 h。雨峰系数r取值如下:P=3年时,r=0.4;P=5年时,r=0.45;P=10年时,r=0.5。设计降雨情况如图2所示。其中,降雨重现期在3年时的总降雨量和峰值雨强分别为59.60 mm和171.82 mm·h−1,重现期为5年时对应的总降雨量和峰值雨强分别为71.24 mm和205.37 mm·h−1,重现期为10年时对应的总降雨量和峰值雨强的分别为87.14 mm和251.21 mm·h−1。

1.4 水质检测及分析方法

水样的监测指标包括化学需氧量(COD)、总磷(TP)、氨氮(NH3-N)、悬浮颗粒物(SS)。测试方法:SS采用重量法,TP采用钼酸铵分光光度法,COD用重铬酸钾快速消解法测定,NH3-N用纳氏试剂光度法测定。

事件平均浓度(CEMC)是整个降雨过程中所有瞬时污染物浓度对流量的加权平均值,其计算方法如式(2)所示。

CEMC=MV=∫CtQtdt∫Qtdt=∑mj=1CjQj∑mj=1Qj (2) 式中:M为降雨事件中污染物总量,mg;V为降雨事件中总流量,L;Ct为t时刻污水中污染物的瞬时浓度,mg·L−1;Qt为t时刻的瞬时流量,L·h−1;t为发生溢流的时间,h;Cj为第j次取样污染物浓度,mg·L−1;Qj为第j次取样时的流量,L·h−1;m为径流事件次数。

排入受纳水体中的污染物总量分为2部分,一是因为降雨而产生的溢流污染负荷,二是日常污水直排产生的污染负荷。其中因降雨产生的溢流污染负荷是考察的重点,可按式(3)计算。

Mj=∑Ci[ΨS(hi−h0)+Qdti] (3) 式中:Mj为第j个合流制溢流口因降雨全年排污量,mg;Ci为第i场降雨溢流污水污染物浓度EMC值,mg·L−1;Ψ为综合径流系数;S为合流制管网服务面积,m2;hi为第i场降雨场次降雨量,mm;h0为形成径流所需降雨量,mm;Qd为日常污水日均排放量,L·h−1;ti为第i场降雨历时,h。

1.5 模型校核

本项目采用遗传算法对水量模型参数进行了自动校核,对于水质模型参数采用了人工校核。选取COD、SS、TP、NH3-N等4种水质指标作为参考来分析污染状况。根据SWMM使用手册及相关研究数据,初步确定模型水质参数,而后再根据现场实测数据对此参数进行调整,校准结果见表1。

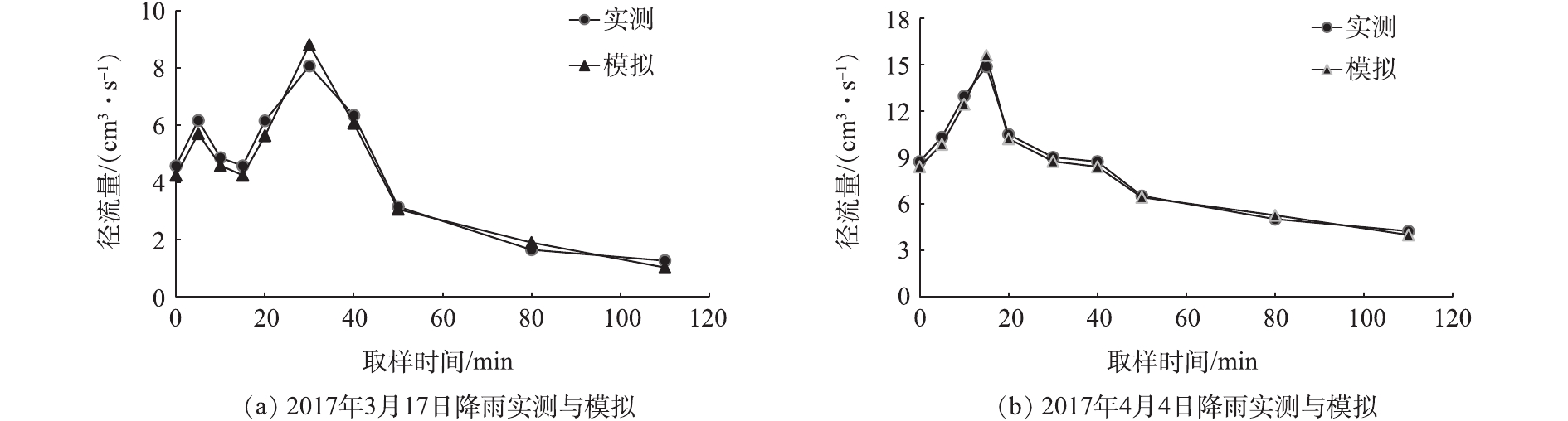

表 1 SWMM水质模型参数Table 1. Basic parameters in water quality model of SWMM水质指标 屋顶 路面 绿地 最大累积量/(kg·(hm2)−1) 半饱和累积时间/d 冲刷系数 冲刷指数 最大累积量/(kg·(hm2)−1) 半饱和累积时间/d 冲刷系数 冲刷指数 最大累积量/(kg·(hm2)−1) 半饱和累积时间/d 冲刷系数 冲刷指数 COD 80 10 0.006 1.8 170 10 0.007 1.8 40 10 0.004 1.2 SS 140 10 0.007 1.8 270 10 0.008 1.8 60 10 0.004 1.2 NH3-N 4 10 0.002 1.5 5 10 0.002 1.5 2 10 0.001 1.2 TP 0.4 10 0.002 1.6 0.2 10 0.002 1.6 0.6 10 0.001 1.2 利用研究区于 2017年3月6日和2017年4月4日监测的2场实际降雨监测数据对模型进行模拟精度校核。由图3可见,模型模拟的流量过程与实测径流过程拟合较好,洪峰流量的模拟值和实测值相接近,表明校核后模拟精度较好,可满足工程需要。

2. 管网溢流污染模拟

2.1 设计暴雨模拟分析

排水系统在暴雨重现期分别为3、5、10年,降雨历时均为2 h的降雨条件下,溢流情况的模拟结果如表2所示。由表2可知,在暴雨重现期为3年时,截流水量仅为44万m3,溢流水量为427.95 m3,溢流水量远大于截流的水量,截流比例仅为9%,各类污染物的溢流量也均超过截流量,截流比例均不超过25%,这说明有大量的污水通过溢流管道流入巡司河中,对巡司河的水生态环境造成破坏。随着暴雨重现期的升高,截流量减小,溢流量增大,截流比例也显著减小。在实际情况下,如果溢流污水大于50万m3,城市自然水体的自净能力将无法处理溢流污水所造成的污染,很有可能导致水质下降,甚至变成黑臭水体[16]。

表 2 不同重现期下的降雨模拟结果Table 2. The results of rainfall simulation under different return periods重现期/年 截流量 溢流量 截流比例 水量/(万m3) 污染物/t 水量/(万m3) 污染物/t 水量/% 污染物/% COD NH3-N TP SS COD NH3-N TP SS COD NH3-N TP SS 3 44 23.79 3.12 0.39 15.97 427.95 126.88 11.49 1.43 73.33 9 16 21 21 18 5 44.48 21.75 2.86 0.36 15.07 481.51 121.65 11.67 1.45 72.86 8 15 20 20 17 10 46.7 18.77 2.36 0.29 13.45 634.6 127.77 12.58 1.57 75.69 7 13 16 16 15 2.2 年降雨模拟分析

采用武汉市2014年和2015年的全年降雨数据对排水管道进行模拟,排水系统发生的溢流次数是全年溢流,结果如表3所示。由表3可以看出,全年溢流的污水接近2 000万m3,流入地表水中的COD约3 300 t、NH3-N约500 t、TP约60 t、SS约2 000 t,截流比例均小于70%,说明现有的合流制管网排水能力过小,一旦发生降雨,很有可能在雨水口附近产生路面积水,造成城市内涝,也会有大量的溢流污水流入地表水中,对环境造成破坏。由此可以推测,降雨发生后,管道内流量快速增加、排水管网超负荷运行是造成溢流量增加和城市内涝的主要原因。

表 3 全年降雨模拟结果Table 3. Simulation results of annual rainfall年份 截流量 溢流量 水量/(万m3) 污染物/t 水量/(万m3) 污染物/t COD NH3-N TP SS COD NH3-N TP SS 2014 3 100.87 7231.75 1 147.28 143.41 43 35.1 1 977.37 3 377.84 515.62 64.43 2 038.75 2015 3 071.72 7 298.67 1 160.9 145.11 4 376.61 1 827.29 3 248.13 500.29 62.52 1 953 因此,如何快速有效的处理这部分径流污水,是解决合流制溢流污染问题的关键。在本次模拟中,欲满足溢流控制规定,则需要将年溢流量控制在50万m3以下,截流比例控制在85%以上,年溢流次数控制在10以下。拟根据研究区域的土地利用情况,设计合理的溢流污染控制方案,增大该地区排水系统的调蓄能力及输水能力,减少溢流次数,从源头上降低溢流污水量,从根本上改变传统排水系统易渍涝、易污染的状况[17]。

3. 研究区域溢流控制模拟

3.1 工程措施组合方案

根据研究区控制目标和总体规划,制定一套可行的方案,在实际工程中通常采用多种工程措施协同作用的方案,发挥各工程措施的特点,实现控制效果最大化。通过分析比较几种典型的工程措施发现,扩增管径的综合效能相对较低,铺设新的输水管道由于建造时需要破坏大量的道路,会长时间影响交通情况,给人们正常工作带来很大影响,此外雨水花园造价和维护成本又过高。因此,根据目标需求以及研究区域场地条件,综合选择了3种工程措施:雨水调蓄池能够缓解管道负荷、减少溢流污水量及溢流次数和滞后洪峰时刻,是一种行之有效的“中端”治理措施[18-19];排水泵站能够有效降低降雨时排水系统所受到的冲击,控制溢流效果显著,且占地较少;箱涵具有较大的调蓄能力及输水能力,所以在安装箱涵之后,可以无需安装排水泵站来调控管网水量,然而在实际应用中,箱涵施工难度较大,而且需要较大的占地面积,对区域整体规划影响较大[20]。

措施布设情况见图4。D1及D2均采用雨水调蓄池和截流泵站组合措施,在晒湖箱涵的末端修建雨水调蓄池和截流泵站,武泰闸片区的溢流污水利用DN1500管道输送至截流泵站。首先利用截流泵站截流溢流污水,超出泵站截流能力的污水再被雨水调蓄池截流,没有被截流的污水最终溢流至巡司河,其中D1被截流的污水输送至下游处理设施,D2被截流的污水就地进行处理,D3利用雨水调蓄池和箱涵组合措施截流来自武泰闸片区及晒湖片区的溢流污水,降雨初期排渠箱涵闸门关闭,污水先流入调蓄池,调蓄池蓄满后关闭进调蓄池闸门,污水进入下游截流箱涵,最后输送送至下游处理设施,截流箱涵满负荷以后,污水溢流入巡司河,晴天利用排空泵站排空调蓄池。

3.2 模拟结果与分析

3.2.1 设计重现期模拟

选取3、5、10年3种降雨情景(降雨历时均为2h)对3种方案模型进行模拟分析,探究各种方案在不同降雨强度下的控制效果,模拟结果见图5和表4。

表 4 场降雨模拟结果Table 4. Simulation results of pollutant loads under different rainfall return periods方案 重现期/年 截流量 溢流量 截流比例 水量/(万m3) 污染物/t 水量/(万m3) 污染物/t 水量/% 污染物/% COD NH3-N TP SS COD NH3-N TP SS COD NH3-N TP SS 3 199.62 67.26 7.01 0.87 40.71 410.62 100.19 6.62 0.82 45.96 33 40 51 52 47 D1 5 204.96 56.06 5.49 0.68 34.62 545.4 110.44 7.82 0.97 50.52 27 34 41 41 41 10 214.67 44.32 3.97 0.49 28.45 919.01 127.7 10.42 1.3 58.6 19 26 28 28 33 3 141.83 54.86 5.69 0.71 32.81 459.57 125.07 9.61 1.16 61.81 24 30 37 38 35 D2 5 144.56 46.27 4.61 0.57 28.13 577.35 131.58 10.47 1.27 65.54 20 26 31 31 30 10 149.56 38.08 3.66 0.45 24.88 862.23 135.59 11.67 1.42 67.27 15 22 24 24 27 3 24.66 6.62 0.52 0.1 5.35 10.78 1.35 0.16 0.03 1.16 70 83 76 75 82 D3 5 25.26 5.97 0.49 0.09 5.02 14.47 1.51 0.19 0.04 1.39 64 80 72 70 78 10 26.7 5.84 0.47 0.09 4.89 25.34 2.02 0.26 0.05 1.88 51 74 64 63 72 可以看出,在3年至10年的降雨重现期的条件下,D2的截流能力最差,径流总量分别减少了24%、20%、15%,D3的截流效果最好,径流总量分别减少了75%、68%、54%,但各方案的控制效果均好于现状排水系统,由模拟结果可以看出调蓄池对于降雨径流具有截流减量的作用。D2对SS截流比例分别为35%、30%、27%,D1对SS截流比例分别为47%、41%、33%,D3对SS截流比例分别为82%、78%、72%。由模拟结果可知,雨水调蓄池使得城市暴雨所带来的非点源污染程度有所降低,对污染物截流具有一定的强化效果,对污染物骤增骤减的现象有所缓解,但是随着重现期的增大,暴雨强度增加,雨水调蓄池对各污染物截流效果会随之减小,主要原因是管道输水能力有限,当降雨量随重现期增大而增大时,各措施的截流效果会逐渐减弱。D3对总径流量和污染物有较强的截流效果,这是由箱涵和雨水调蓄池共同作用的结果。

对比表1可以看出,D1和D2的溢流量与现状下的溢流量相差不大,但截流量有着显著提高,比现状下的截流量提高了约200 m3,因此,导致溢流水量和污染物的截流比例有所提高。虽然截流量的提高能使雨水口附近道路处的路面积水减少,城市内涝问题有所缓解,但任有大量的溢流污水流入地表水中,对环境造成破坏。D3的截流效果最好,不仅溢流量最小,截流效率也是3个方案里最大的,说明采用D3能使溢流进入巡司河的污水减少。因为箱涵具有较大的调蓄能力及输水能力,而雨水调蓄池容积和水泵流量较小,而该地区主要用于截流来自箱涵的污水,根据管道拓扑关系分析,来自晒湖箱涵的污水占总水量的73%,故导致调蓄池和水泵的负荷增大,溢流污水增加,截流效率降低。D2在泵站流量与调蓄池容积的设置上与D1类似,但是由于就地一级强化处理的最大流量为2.5 m3·s−1,使得调蓄池与泵站的共同截流污水的能力受到限制,因此截流效率最低。

3.2.2 往年降雨控制效果分析

由上述模拟分析对比得知,D3对于溢流污染控制效果远优于其他方案。在连续降雨条件下,再分别对3个方案进行模拟分析,探究3种方案在不同降雨强度下对污染物溢流量的截流能力,模拟结果见表5。

表 5 不同年份下污染物溢流模拟结果Table 5. Simulation results of pollutant overflow under different years方案 年份 溢流次数 截流量 溢流量 截流比例 水量/(万m3) 污染物/t 水量/(万m3) 污染物/t 水量/% 污染物/% COD NH3-N TP SS COD NH3-N TP SS COD NH3-N TP SS D1 2014 31 5 250.56 8 006.96 1 256.61 157.05 4 813.81 324.25 68.86 5.54 0.69 36.23 94.18 99.15 99.56 99.56 99.25 2015 20 4 935.09 7 761.74 1 223.47 152.94 4 661.99 332.28 59.81 5.13 0.64 31.99 93.69 99.24 99.58 99.59 99.32 D2 2014 46 4 660.75 10 312.88 1 631.59 203.95 6 182.17 506.15 130.62 11.85 1.47 77.03 90.20 98.75 99.28 99.28 98.77 2015 32 4 527.42 10 302.81 1 635.39 204.42 6 177.69 498.8 114.74 10.72 1.33 66.13 90.08 98.90 99.35 99.35 98.94 D3 2014 9 1 109.13 737.92 109.96 22.35 792.43 158.8 20.34 2.46 0.5 16.75 90.50 97.30 97.80 97.80 97.90 2015 8 862.5 533.48 74.81 15.1 565.62 142.39 14.65 1.92 0.39 12.99 90.80 97.30 97.50 97.50 97.80 可以看出,3种方案的水量总体的截流比例均大于90%,总体水质的截流比例均在95%以上,其中D3在2014年和2015年的溢流量分别为158.8 m3和142.39 m3,在3个方案中最少,对比表2现状下的模拟结果,年溢流水量平均减少了1 751.7万m3、COD减少了3 295.5 t、NH3-N减少了505.8 t、TP减少了63.1 t、SS减少了1 981.1 t,溢流问题得到了极大的缓解,控制污染成效显著。D2和D1的截流水量约为D3的5倍,说明在污水的调蓄和输送方面,能力稍有不足,较高的截流量会使排水管网长期处于高负荷状态,在溢流的污染物方面,3种方案下所溢流的NH3-N和TP差距不大,但溢流的水量、COD和SS差距较大,D2和D1的溢流水量比D3多出约200 t,且只有D3的年溢流次数小于10,这说明在年降雨量相同时,采用D3可以减少溢流进入巡司河的水量和污染物。

虽然溢流水量得到了有效的控制,但降雨后短时间内管道流量较大,依然存在积水和溢流隐患。这一问题反应出对合流制溢流污染的问题治理不能仅依赖于排水系统的改造,绿色设施(透水铺装、绿色屋顶、生物滞留池等)的相对缺乏,使得对径流雨水的截流、蓄水和削峰作用无法发挥[21],导致降雨径流快速汇入排水管道,使得管道内流量短时间内激增。过度依赖于排水系统改造,溢流控制效果会有所降低,应结合绿色设施,在控制溢流污染的同时,兼顾水质提升和美化环境,充分发挥各项措施的优势特点。

4. 结 论

1)SWMM模型能够有效模拟溢流污染的情况,在武汉地区适应性较好,且能对模拟效果进行量化,可作为CSO溢流污染控制和治理的有效工具,为更好的城市生态系统建设和合流制管网改造提供科学依据。

2)对武汉市巡司河区域分别构建现状模型、改造方案模型,并进行了模拟和对比分析,结果表明,通过D3在全年降雨情景模拟时,可使巡司河区域年溢流次数降到10次以下,水量总体的截流比例均大于90%,总体水质的截流比例均在95%以上,年溢流水量平均减少了1 751.7万m3、COD减少了3 295.5 t、NH3-N减少了505.8 t、TP减少了63.1 t、SS减少了1 981.1 t,有效的缓解了合流制管道溢流问题。

3)箱涵-雨水调蓄从组合具有较大的调蓄能力及输水能力,通过箱涵与调蓄池结合,在3年、5年和10年的降雨重现期条件下,对径流总量截流比例分别为69%、63%、51%,对COD截流比例分别为83%、79%、74%,对NH3-N截流比例分别为76%、71%、64%,对TP截流比例分别为74%、70%、62%,对SS截流比例分别为82%、78%、72%。

-

表 1 HFPO-TA和PFOA的分子式、结构式和物理化学性质

Table 1. Molecular formula, structural formula and physicochemical properties of HFPO-TA and PFOA

化学名称Chemical name 分子式Molecular formula 水溶性/(g·L−1)Water solubility[17] lg Kow lg Kpw pKa 化学结构式Structure HFPO-TA 六氟环氧丙烷三聚体羧酸 C9HF17O4 100—200(25 ℃) 5.55[17] 3.85 -0.07[17] PFOA 全氟辛烷羧酸 C8HF15O2 >500(25 ℃) 4.81[18] 3.43 -0.50—4.20[19] 注:lg Kow表示辛醇-水分配系数;lg Kpw表示蛋白-水分配系数,lg Kpw是根据Debruyn和Gobas[20]提出的回归方程lg Kpw = 0.57× lg Kow + 0.69计算得到. Note: lg Kow, octanol-water partition coefficient; lg Kpw, protein-water partition coefficient; lg Kpw is calculated according the regression equation lg Kpw = 0.57× lg Kow + 0.69 proposed by Debruyn and Gobas[20]. 表 2 HFPO-TA和PFOA在不同环境中的浓度水平

Table 2. Concentration levels of HFPO-TA and PFOA in different environments

采样点Sampling point HFPO-TA PFOA 参考文献Reference 地表水/(ng·L−1) 长江(重庆—上海段) <LOQ—1.29 3.48—36.5 [35] 黄河(甘肃、河南和山东段) <LOQ—0.74 0.15—4.92 [35] 珠江(广东段) <LOQ—9.20 0.40—52.8 [35] 辽河(辽宁段) 0.13—0.61 5.28—12.3 [35] 淮河(河南—安徽段) 0.28—0.61 4.24—9.06 [35] 巢湖 0.20—1.08 7.00—10.5 [35] 英国Thames River(Oxford, Landon) 0.05—0.21 5.56—11.7 [35] Rhine River(Germany-Netherlands) <LOQ—0.31 0.86—3.66 [35] 美国Delaware River(Trenton— Frederica) <LOQ—4.33 2.12—14.9 [35] 瑞典Mälaren Lake(Orebro, Stockholm) <LOQ—0.39 1.07—3.34 [35] 韩国Han River(Seoul) 0.16—0.58 1.84—4.53 [35] 山东小清河(上游、支流(东猪龙河,预备河)、下游) 3.99—68500 15.4—197000 [17] 南黄海(江苏省海岸线) 0.92—6.68 10.7—30.8 [31] 望虞河(常熟) (1.50) (36.0) [36] 海河(天津、北京) 0.004—3.83 0.28—21.2 [37] 鄱阳湖 0.46—3.40(0.95) 1.80—17.0(6.50) [32] 太湖(2016年) 0.12—34.8(0.38) 3.15—44.5(18.0) [36] 太湖(2019年) (0.30) (21.0) [36] 太湖(2021年) (1.72) (28.2) [36] 德胜河(常州段)(枯水期) (0.08) (10.0) [38] 德胜河(常州段)(丰水期) (0.32) (6.30) [38] 长江(常州段)(枯水期) (0.07) (9.40) [38] 长江(常州段)(丰水期) (0.39) (6.70) [38] 沉积物/(pg·g -1 dw(干重))和悬浮物/(pg·L−1) 南黄海沉积物(江苏省海岸线) 7.57—113 91.7—1826 [31] 鄱阳湖沉积物 11.0—480(200) 7.10—70.0(31.0) [32] 鄱阳湖悬浮物 120—1200(410) 11.0—1100(99.0) [32] 污水处理厂和工业园区地表水/(ng·L−1) 常熟氟工业区WWTP出水 360(中值) 19232(中值) [36] 常熟氟工业区地表水 (3.31) (533) [36] 地下水和饮用水/(ng·L−1) 黄土高坡地下水 (0.31) 0.41—99.9(6.42) [33] 常熟地下水 0.07—38.0(2.15) 0.25—566(93.3) [30] 桓台地下水 3.89—462 24.8—462 [39] 桓台村庄自来水 n.d. —81.2 n.d. —198 [25] 常州公共供水系统(冬季) n.d. —(0.21) (8.30)—(9.60) [38] 常州公共供水系统(夏季) (0.44)—(0.52) (7.10)—(7.50) [38] 土壤和室内外灰尘/(ng·g−1) 常熟表层土壤 0.02—0.06(0.02) 0.34—5.30(1.56) [30] 桓台县FIP附近土壤 53.7—2910 22.8—185 [39] 杭州垃圾填埋场附近土壤 <LOQ (0.80) [40] 桓台县室外灰尘 189—4250 24.6—459 [39] 桓台县室内灰尘 112—21723(4014) 20.2—1503(421) [25] 注:n.d.表示未检出,LOQ表示定量限,括号里的数字表示平均值. Note: n.d., not detected; LOQ, limit of quantitation; the figures in brackets mean the average value. 表 3 HFPO-TA和PFOA在生物体内分布

Table 3. Distribution of HFPO-TA and PFOA in organism

生物Organism HFPO-TA PFOA 参考文献Reference 小清河 鲤鱼血/(ng·mL−1)(中值) 1510 2190 [17] 鲤鱼肝/(ng·g−1 ww (湿重))(中值) 587 449 [17] 鲤鱼肉/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重))(中值) 118 73.6 [17] 山东桓台 雄黑斑蛙肾/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重)) (59.3) (43.6) [18] 雄黑斑蛙肝/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重)) (13.4) (5.95) [18] 雄黑斑蛙睾丸/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重)) (3.24) (2.54) [18] 雄黑斑蛙皮肤/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重)) (6.10) (2.47) [18] 雄黑斑蛙肺/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重)) (3.93) (1.74) [18] 雄黑斑蛙心/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重)) (7.39) (2.30) [18] 雄黑斑蛙胃/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重)) (1.96) (0.94) [18] 雄黑斑蛙肠/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重)) (0.93) (0.63) [18] 雄黑斑蛙肉/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重)) (1.76) (1.06) [18] 雄黑斑蛙残体/(ng·g−1 ww(湿重)) (1.08) (1.06) [18] 小麦/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) 2.81—5.37(3.71) 3.99—56.8(35.1) [25] 玉米/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) 0.39—1.09(0.68) 0.31—4.56(1.59) [25] 蔬菜/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) n.d. —341(45.1) 3.44—768(130) [25] 牛奶/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) 0.74—10.9(2.47) n.d. —2.74(0.86) [25] 鸡蛋/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) 0.11—2014(390) 0.30—1316(305) [25] 海产品/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) n.d. —4.63(1.14) 0.42—87.7(16.8) [25] 小清河河口 浮游生物/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) 13.6—62.4(34.6) 64.3—165(97.5) [10] 双壳类/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) 0.84—13.7(9.14) 52.7—682(339) [10] 甲壳类/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) 20.9—138(72.2) 136—171(148) [10] 腹足类/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) 2.62—3.62(3.16) 44.7—47.7(46.0) [10] 鱼类/(ng·g−1 dw(干重)) 11.9—188(67.4) 23.5—319(138) [10] 北京 健康女性卵泡液/(ng·mL−1) n.d. —0.36 1.15—596 [55] 山东桓台 居民血清/(ng·mL−1)(中值)(2016年) 2.93 126 [17] 居民血清/(ng·mL−1)(中值)(2019—2020年) 1.93 172 [56] 居民尿液/(ng·mL−1) 0.75—194(22.7) 0.19—34.2(7.30) [25] 居民头发/(ng·g−1) n.d. —52.1(14.7) 18.3—1390(277) [25] 注:n.d.表示未检出,括号里的数字表示平均值. Note: n.d., not detected; the figures in brackets mean the average value. -

[1] ZHANG C H, McELROY A C, LIBERATORE H K, et al. Stability of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in solvents relevant to environmental and toxicological analysis[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2022, 56(10): 6103-6112. [2] KIRKWOOD K I, FLEMING J, NGUYEN H, et al. Utilizing pine needles to temporally and spatially profile per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2022, 56(6): 3441-3451. [3] BUCK R C, FRANKLIN J, BERGER U, et al. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: Terminology, classification, and origins[J]. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 2011, 7(4): 513-541. doi: 10.1002/ieam.258 [4] WANG Z Y, DeWITT J C, HIGGINS C P, et al. A never-ending story of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs)?[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(5): 2508-2518. [5] GOBELIUS L, HEDLUND J, DÜRIG W, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in Swedish groundwater and surface water: Implications for environmental quality standards and drinking water guidelines[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(7): 4340-4349. [6] MARTIN J W, SMITHWICK M M, BRAUNE B M, et al. Identification of long-chain perfluorinated acids in biota from the Canadian Arctic[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2004, 38(2): 373-380. [7] LAM N H, CHO C R, KANNAN K, et al. A nationwide survey of perfluorinated alkyl substances in waters, sediment and biota collected from aquatic environment in Vietnam: Distributions and bioconcentration profiles[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2017, 323: 116-127. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.04.010 [8] KANNAN K, TAO L, SINCLAIR E, et al. Perfluorinated compounds in aquatic organisms at various trophic levels in a great lakes food chain[J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2005, 48(4): 559-566. doi: 10.1007/s00244-004-0133-x [9] STEENLAND K, FLETCHER T, SAVITZ D A. Epidemiologic evidence on the health effects of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2010, 118(8): 1100-1108. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901827 [10] LI Y N, YAO J Z, ZHANG J, et al. First report on the bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids in estuarine food web[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2022, 56(10): 6046-6055. [11] SHENG N, PAN Y T, GUO Y, et al. Hepatotoxic effects of hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid (HFPO-TA), a novel perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) alternative, on mice[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(14): 8005-8015. [12] SONG X W, VESTERGREN R, SHI Y L, et al. Emissions, transport, and fate of emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from one of the major fluoropolymer manufacturing facilities in China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(17): 9694-9703. [13] WANG Z Y, COUSINS I T, SCHERINGER M, et al. Fluorinated alternatives to long-chain perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs), perfluoroalkane sulfonic acids (PFSAs) and their potential precursors[J]. Environment International, 2013, 60: 242-248. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.08.021 [14] STRYNAR M, DAGNINO S, McMAHEN R, et al. Identification of novel perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids (PFECAs) and sulfonic acids (PFESAs) in natural waters using accurate mass time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TOFMS)[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(19): 11622-11630. [15] GEBBINK W A, van ASSELDONK L, van LEEUWEN S P J. Presence of emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in river and drinking water near a fluorochemical production plant in the Netherlands[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(19): 11057-11065. [16] EVICH M G, DAVIS M J B, McCORD J P, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment[J]. Science, 2022, 375(6580): eabg9065. doi: 10.1126/science.abg9065 [17] PAN Y T, ZHANG H X, CUI Q Q, et al. First report on the occurrence and bioaccumulation of hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid: An emerging concern[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(17): 9553-9560. [18] CUI Q Q, PAN Y T, ZHANG H X, et al. Occurrence and tissue distribution of novel perfluoroether carboxylic and sulfonic acids and legacy per/polyfluoroalkyl substances in black-spotted frog (Pelophylax nigromaculatus)[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(3): 982-990. [19] GOSS K U. The pKa values of PFOA and other highly fluorinated carboxylic acids[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42(2): 456-458. [20] DEBRUYN A M H, GOBAS F A P C. The sorptive capacity of animal protein[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2007, 26(9): 1803-1808. doi: 10.1897/07-016R.1 [21] 中华人民共和国工业和信息化部. 《国家鼓励的有毒有害原料(产品)替代品目录(2016年版)》 [EB/OL]. 2016-12-27. CHINESE MINISTRY OF INDUSTRY AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY. List of toxic and hazardous raw materials (products) substitutes encouraged by the state[EB/OL]. 2016-12-27.

[22] 钱力波, 黄美薇, 苏兆本, 等. 六氟环氧丙烷三聚体羧酸(HFPO-TA)环境和生态毒性研究进展[J]. 有机氟工业, 2021(4): 31-38. QIAN L B, HUANG M W, SU Z B, et al. Research progress in environmental and ecological toxicity of hexafluoropropene oxide trimer carboxylic acid(HFPO-TA)[J]. Organo-Fluorine Industry, 2021(4): 31-38 (in Chinese).

[23] OGINO K, MURAKAMI H, ISHIKAWA N, et al. Synthesis of fluorinated surfactants containing hexafluoropropene oxide as a hydrophobic group and properties of the solutions[J]. Journal of Japan Oil Chemists’ Society, 1983, 32(2): 96-101. doi: 10.5650/jos1956.32.96 [24] 王汉利, 李秀芬, 石慧. 无PFOA的含氟表面活性剂对PVDF树脂合成的影响[J]. 涂料技术与文摘, 2015, 36(11): 9-12. WANG H L, LI X F, SHI H. Influence of PFOA-free fluoro-containing surfactant on synthesis of PVDF resin[J]. Coatings Technology & Abstracts, 2015, 36(11): 9-12 (in Chinese).

[25] FENG X M, CHEN X, YANG Y, et al. External and internal human exposure to PFOA and HFPOs around a mega fluorochemical industrial park, China: Differences and implications[J]. Environment International, 2021, 157: 106824. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106824 [26] 陆雯, 张冰冰, 朱鹰, 等. PFOA替代品研究及其在氟橡胶中的应用[J]. 有机氟工业, 2011(2): 20-23. LU W, ZHANG B B, ZHU Y, et al. Study on the PFOA substitute and its application in the polymerization of fluoroelastomer[J]. Organo- Fluorine Industry, 2011(2): 20-23 (in Chinese).

[27] RICE P A, COOPER J, KOH-FALLET S E, et al. Comparative analysis of the physicochemical, toxicokinetic, and toxicological properties of ether-PFAS[J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2021, 422: 115531. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2021.115531 [28] SIANESI D, ZAMBONI V, FONTANELLI R, et al. Perfluoropolyethers: Their physical properties and behaviour at high and low temperatures[J]. Wear, 1971, 18(2): 85-100. doi: 10.1016/0043-1648(71)90158-X [29] JONES W R, SHOGRIN B A, JANSEN M J. Research on liquid lubricants for space mechanisms[J]. Journal of Synthetic Lubrication, 2000, 17(2): 109-122. doi: 10.1002/jsl.3000170203 [30] LIU Z Y, XU C, JOHNSON A C, et al. Exploring the source, migration and environmental risk of perfluoroalkyl acids and novel alternatives in groundwater beneath fluorochemical industries along the Yangtze River, China[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 827: 154413. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154413 [31] FENG X M, YE M Q, LI Y, et al. Potential sources and sediment-pore water partitioning behaviors of emerging per/polyfluoroalkyl substances in the South Yellow Sea[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 389: 122124. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122124 [32] TANG A P, ZHANG X H, LI R F, et al. Spatiotemporal distribution, partitioning behavior and flux of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in surface water and sediment from Poyang Lake, China[J]. Chemosphere, 2022, 295: 133855. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.133855 [33] ZHOU J, LI S J, LIANG X X, et al. First report on the sources, vertical distribution and human health risks of legacy and novel per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater from the Loess Plateau, China[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 404: 124134. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124134 [34] CHEN H, YAO Y M, ZHAO Z, et al. Multimedia distribution and transfer of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) surrounding two fluorochemical manufacturing facilities in Fuxin, China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(15): 8263-8271. [35] PAN Y T, ZHANG H X, CUI Q Q, et al. Worldwide distribution of novel perfluoroether carboxylic and sulfonic acids in surface water[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(14): 7621-7629. [36] YAO J Z, SHENG N, GUO Y, et al. Nontargeted identification and temporal trends of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in a fluorochemical industrial zone and adjacent Taihu Lake[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2022, 56(12): 7986-7996. [37] LI Y, FENG X M, ZHOU J, et al. Occurrence and source apportionment of novel and legacy poly/perfluoroalkyl substances in Hai River Basin in China using receptor models and isomeric fingerprints[J]. Water Research, 2020, 168: 115145. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115145 [38] QU Y X, JIANG X S, CAGNETTA G, et al. Poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in a drinking water treatment plant in the Yangtze River Delta of China: Temporal trend, removal and human health risk[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 696: 133949. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133949 [39] 冯雪敏. 典型环境中新型全氟/多氟化合物的污染特征及人体内外暴露研究[D]. 天津: 南开大学, 2021: 61-105. FENG X M. Pollution characteristics and human external and internal exposure of novel per-/poly-fluoroalkyl substances in typical environment[D]. Tianjin: Nankai University, 2021: 61-105. (in Chinese)

[40] XU C, SONG X, LIU Z Y, et al. Occurrence, source apportionment, plant bioaccumulation and human exposure of legacy and emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in soil and plant leaves near a landfill in China[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 776: 145731. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145731 [41] LEE H J, KIM K Y, HAMM S Y, et al. Occurrence and distribution of pharmaceutical and personal care products, artificial sweeteners, and pesticides in groundwater from an agricultural area in Korea[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 659: 168-176. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.258 [42] XIAO J, WANG L Q, DENG L, et al. Characteristics, sources, water quality and health risk assessment of trace elements in river water and well water in the Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 650: 2004-2012. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.322 [43] LINDSTROM A B, STRYNAR M J, LIBELO E L. Polyfluorinated compounds: Past, present, and future[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(19): 7954-7961. [44] DOMINGO J L, ERICSON-JOGSTEN I, PERELLó G, et al. Human exposure to perfluorinated compounds in Catalonia, Spain: Contribution of drinking water and fish and shellfish[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2012, 60(17): 4408-4415. doi: 10.1021/jf300355c [45] INGELIDO A M, ABBALLE A, GEMMA S, et al. Biomonitoring of perfluorinated compounds in adults exposed to contaminated drinking water in the Veneto Region, Italy[J]. Environment International, 2018, 110: 149-159. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.10.026 [46] APPLEMAN T D, HIGGINS C P, QUIÑONES O, et al. Treatment of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in U. S. full-scale water treatment systems[J]. Water Research, 2014, 51: 246-255. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.10.067 [47] LI Y N, LI J F, ZHANG L F, et al. Perfluoroalkyl acids in drinking water of China in 2017: Distribution characteristics, influencing factors and potential risks[J]. Environment International, 2019, 123: 87-95. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.036 [48] LU Z B, SONG L N, ZHAO Z, et al. Occurrence and trends in concentrations of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in surface waters of Eastern China[J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 119: 820-827. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.045 [49] PAN C G, LIU Y S, YING G G. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in wastewater treatment plants and drinking water treatment plants: Removal efficiency and exposure risk[J]. Water Research, 2016, 106: 562-570. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.10.045 [50] GE H, YAMAZAKI E, YAMASHITA N, et al. Particle size specific distribution of perfluoro alkyl substances in atmospheric particulate matter in Asian cities[J]. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts, 2017, 19(4): 549-560. [51] 何鹏飞, 张鸿, 李静, 等. 深圳市大气中全氟化合物的残留特征[J]. 环境科学, 2016, 37(4): 1240-1247. doi: 10.13227/j.hjkx.2016.04.007 HE P F, ZHANG H, LI J, et al. Residue characteristics of perfluorinated compounds in the atmosphere of Shenzhen[J]. Environmental Science, 2016, 37: 1240-1247 (in Chinese). doi: 10.13227/j.hjkx.2016.04.007

[52] 崔毓莹, 牛夏梦, 唐佳伟, 等. 北京市典型垃圾填埋场渗滤液中PFASs污染水平研究[J]. 环境化学, 2019, 38(9): 2038-2046. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2018120601 CUI Y Y, NIU X M, TANG J W, et al. Distribution and pollution level of PFASs in leachate from typical refuse landfills in Beijing[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2019, 38(9): 2038-2046 (in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2018120601

[53] LIU Z Y, XU C, JOHNSON A C, et al. Source apportionment and crop bioaccumulation of perfluoroalkyl acids and novel alternatives in an industrial-intensive region with fluorochemical production, China: Health implications for human exposure[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022, 423: 127019. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127019 [54] GEBBINK W A, van LEEUWEN S P J. Environmental contamination and human exposure to PFASs near a fluorochemical production plant: Review of historic and current PFOA and GenX contamination in the Netherlands[J]. Environment International, 2020, 137: 105583. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105583 [55] KANG Q Y, GAO F M, ZHANG X H, et al. Nontargeted identification of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in human follicular fluid and their blood-follicle transfer[J]. Environment International, 2020, 139: 105686. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105686 [56] YAO J Z, PAN Y T, SHENG N, et al. Novel perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids (PFECAs) and sulfonic acids (PFESAs): Occurrence and association with serum biochemical parameters in residents living near a fluorochemical plant in China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(21): 13389-13398. [57] INOUE Y, HASHIZUME N, YAKATA N, et al. Unique physicochemical properties of perfluorinated compounds and their bioconcentration in common carpCyprinus carpio L[J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2012, 62(4): 672-680. doi: 10.1007/s00244-011-9730-7 [58] LIU M L, DONG F F, YI S J, et al. Probing mechanisms for the tissue-specific distribution and biotransformation of perfluoroalkyl phosphinic acids in common carp (Cyprinus carpio)[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(8): 4932-4941. [59] CHEN F F, GONG Z Y, KELLY B C. Bioavailability and bioconcentration potential of perfluoroalkyl-phosphinic and-phosphonic acids in zebrafish (Danio rerio): Comparison to perfluorocarboxylates and perfluorosulfonates[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 568: 33-41. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.215 [60] CHEN M, GUO T T, HE K Y, et al. Biotransformation and bioconcentration of 6: 2 and 8: 2 polyfluoroalkyl phosphate diesters in common carp (Cyprinus carpio): Underestimated ecological risks[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 656: 201-208. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.297 [61] SUN S J, WANG J S, YAO J Z, et al. Transcriptome analysis of 3D primary mouse liver spheroids shows that long-term exposure to hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid disrupts hepatic bile acid metabolism[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 812: 151509. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151509 [62] XIN Y, REN X M, WAN B, et al. Comparative in vitro and in vivo evaluation of the estrogenic effect of hexafluoropropylene oxide homologues [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(14): 8371-8380. [63] PENG B X, LI F F, MORTIMER M, et al. Perfluorooctanoic acid alternatives hexafluoropropylene oxides exert male reproductive toxicity by disrupting blood-testis barrier[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 846: 157313. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157313 [64] PAN Y F, QIN H, ZHENG L, et al. Disturbance in transcriptomic profile, proliferation and multipotency in human mesenchymal stem cells caused by hexafluoropropylene oxides[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2022, 292: 118483. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118483 [65] SHENG N, CUI R N, WANG J H, et al. Cytotoxicity of novel fluorinated alternatives to long-chain perfluoroalkyl substances to human liver cell line and their binding capacity to human liver fatty acid binding protein[J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2018, 92(1): 359-369. doi: 10.1007/s00204-017-2055-1 [66] HAGENAARS A, KNAPEN D, MEYER I J, et al. Toxicity evaluation of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) in the liver of common carp (Cyprinus carpio)[J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2008, 88(3): 155-163. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.04.002 [67] QUIST E M, FILGO A J, CUMMINGS C A, et al. Hepatic mitochondrial alteration in CD-1 mice associated with prenatal exposures to low doses of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)[J]. Toxicologic Pathology, 2015, 43(4): 546-557. doi: 10.1177/0192623314551841 [68] YI S J, CHEN P Y, YANG L P, et al. Probing the hepatotoxicity mechanisms of novel chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl sulfonates to zebrafish larvae: Implication of structural specificity[J]. Environment International, 2019, 133: 105262. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105262 [69] LI K, GAO P, XIANG P, et al. Molecular mechanisms of PFOA-induced toxicity in animals and humans: Implications for health risks[J]. Environment International, 2017, 99: 43-54. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.014 [70] XIE X X, ZHOU J F, HU L T, et al. Oral exposure to a hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid (HFPO-TA) disrupts mitochondrial function and biogenesis in mice[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022, 430: 128376. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128376 [71] LIANG S X, LIANG G Q, ZHANG Y, et al. Profiling biotoxicities of hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid with human embryonic stem cell-based assays[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2022, 116: 34-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2021.08.012 [72] LI C H, REN X M, GUO L H. Adipogenic activity of oligomeric hexafluoropropylene oxide (perfluorooctanoic acid alternative) through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ pathway[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(6): 3287-3295. [73] HU L T, SUN L, ZHOU J F, et al. Impact of a hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid (HFPO-TA) exposure on impairing the gut microbiota in mice[J]. Chemosphere, 2022, 303: 134951. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134951 [74] KE Y C, TONG T L, CHEN J F, et al. Influences of hexafluoropropylene oxide (HFPO) homologues on soil microbial communities[J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 259: 127504. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127504 [75] BAO Y X, CAGNETTA G, HUANG J, et al. Degradation of hexafluoropropylene oxide oligomer acids as PFOA alternatives in simulated nanofiltration concentrate: Effect of molecular structure[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020, 382: 122866. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122866 [76] BENTEL M J, YU Y C, XU L H, et al. Degradation of perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids with hydrated electrons: Structure-reactivity relationships and environmental implications[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(4): 2489-2499. [77] LI C, MI N, CHEN Z H, et al. Photodegradation of hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid under UV irradiation[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2020, 97: 132-140. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2020.05.006 [78] CHEN Z H, TENG Y, HUANG L Q, et al. Rapid photo-reductive destruction of hexafluoropropylene oxide trimer acid (HFPO-TA) by a stable self-assembled micelle system of producing hydrated electrons[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2021, 420: 130436. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.130436 -

下载:

下载: