-

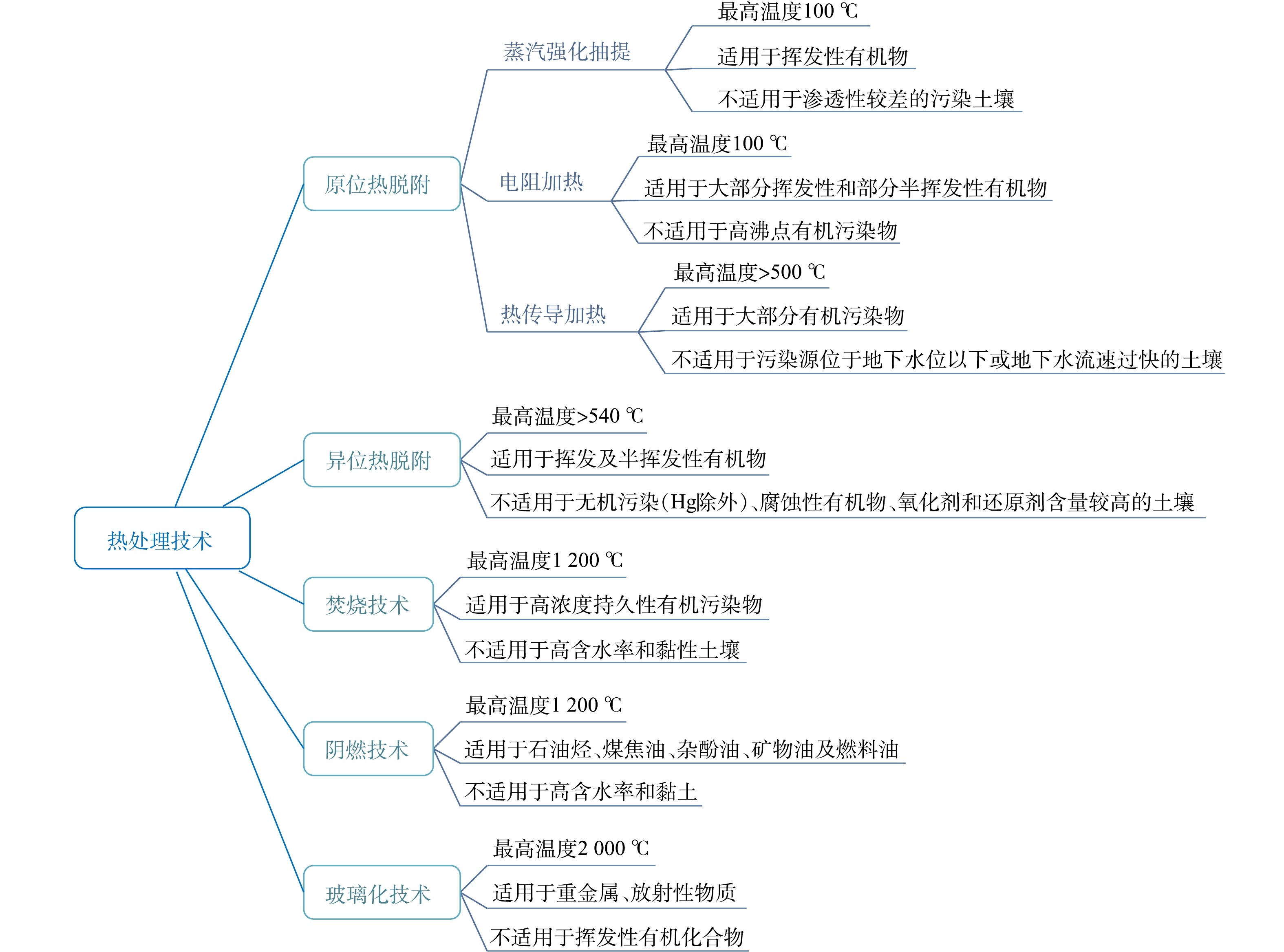

热处理技术常用于去除石油烃 (total petroleum hydrocarbons, TPH)、多环芳烃 (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, PAHs)[1]、多氯联苯(polychlorinated biphenyls, PCBs)[2]、氯苯(chlorobenzene, CBz)[3]等土壤有机污染物。热处理技术类型的选择与污染物性质及其沸点密切相关,不同类型技术有不同的特征和适用场合(见图1)。热处理温度的高低会影响污染物的去除机制:低温热处理时,污染物主要以气相脱附(物理挥发)的形式去除;高温热处理时,污染物则以缩合转化(炭化)、氧化(燃烧)等热反应形式转移[4]。土壤热处理技术快速、高效、彻底、可控,但是有学者担忧会改变土壤结构和性质[5],破坏有机质[6]和微生物菌群[7],从而可能影响再利用特性。关于热处理中有机污染物的化学转化,特别是炭化行为,文献报道并不多见。本文将探讨、分析热处理过程中的炭化行为、炭化机理及其对土壤再利用特性的影响,以期为土壤热处理技术的科学研究与工程实践提供参考。

-

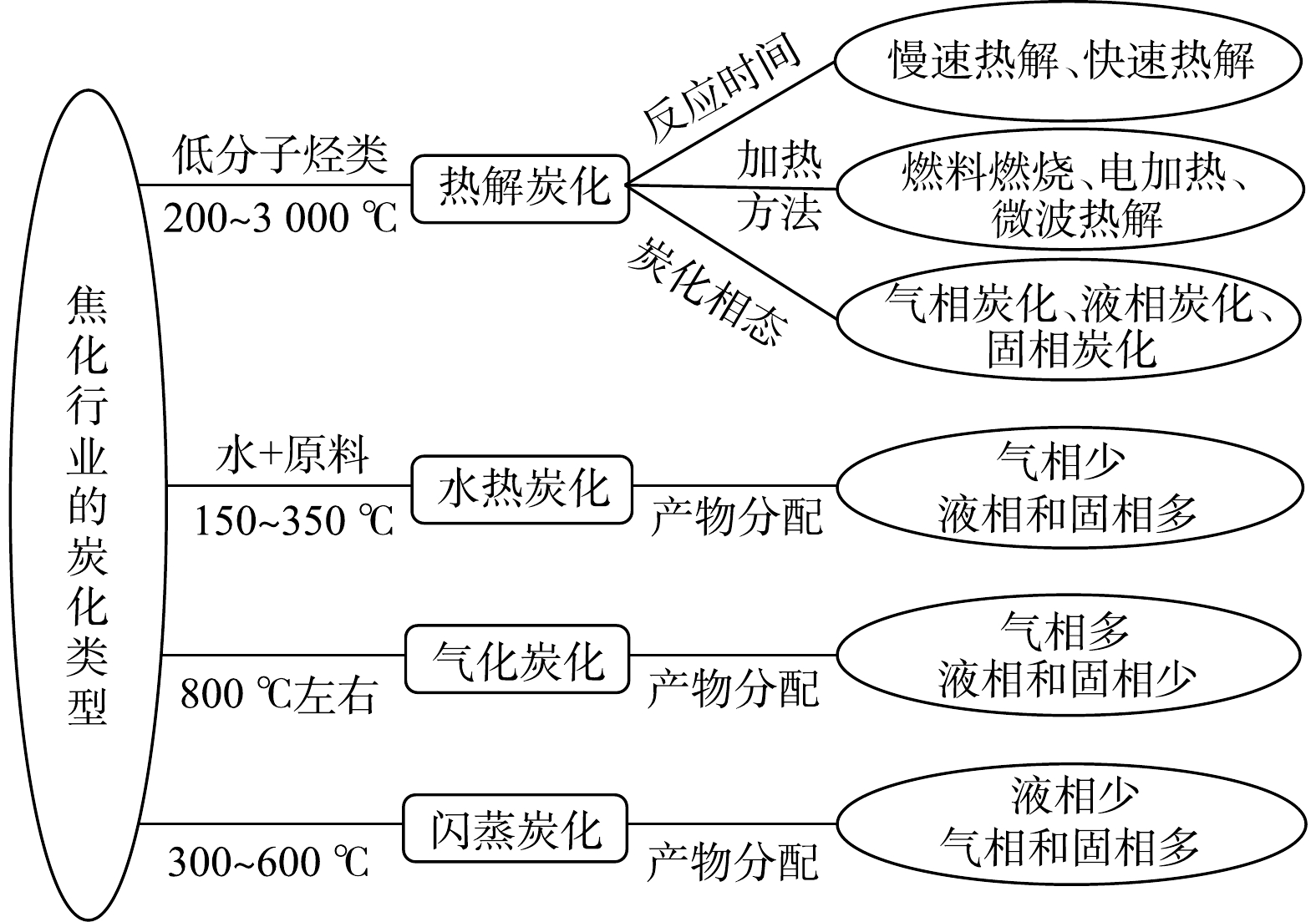

传统焦化行业的炭化反应主要包括热解炭化(pyrolysis)、水热炭化(gasification)、气化炭化(hydrothermal carbonization)和闪蒸炭化(flash carbonization)4类[8],其机理、原料及反应条件各不相同(见图2)。

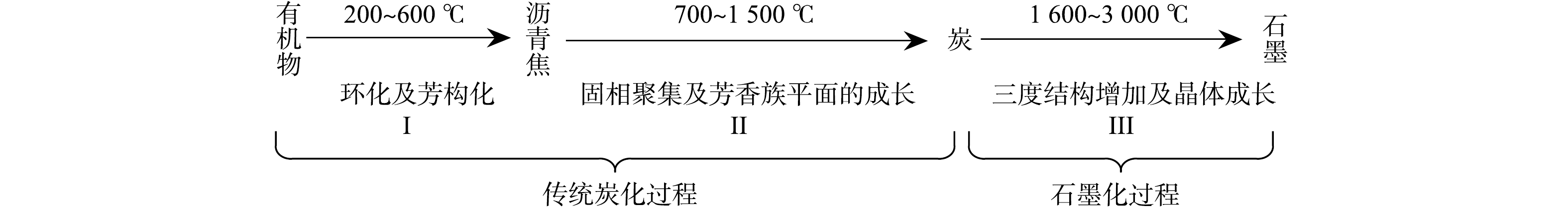

1)热解炭化。热解炭化的温度范围为200~3 000 ℃,其反应过程分为传统炭化I(环化及芳构化)、传统炭化II(固相聚集及芳香族平面的成长)和石墨化炭化III(三度结构增加及晶体成长)3个阶段[9],如图3所示。热解炭化以反应时间分为慢速热解和快速热解;以加热方法分为燃料燃烧、电加热和微波热解[8];以炭化所处相态分为气相炭化、液相炭化和固相炭化[9]。土壤高温热处理过程中发生的有机污染物炭化行为主要属于热解炭化的第一阶段——传统炭化I。

2)水热炭化。水热炭化是以水为介质,将原料置于密闭的水热反应釜中,于150~350 ℃停留1 h以上,最终转化为水热炭,是一种脱水脱羧的加速煤化过程[10]。水热炭化反应经历了水解、脱水、脱羧、芳香化、缩聚等步骤[11],其低温环境导致产生的气体产量非常低,大部分原料转为棕色的煤或溶解在液体中[12]。水热技术可作为重金属(如铅、铯等)污染土壤的一种可靠修复方法[13-14],还可将生物质转化为黄腐酸和腐殖酸,从而用于土壤修复[15]。

3)气化炭化。在气化炭化过程中,在大气压或高压下,生物质在温度为800 ℃左右的气化室被部分氧化。该过程的主要产品是气体,仅形成少量焦炭和液体(炭化的结果)。气化炭化与热解炭化的主要区别在于前者转化环境需要部分氧气,而后者几乎没有氧气[8]。

4)闪蒸炭化。在压力为1~2 MPa下,从原料填充床的底部点火,火势通过炭化床向上流动,阻挡工艺中向下流动的空气。燃烧每千克原料总共约有0.8~1.5 kg空气被输送至反应器中。该方法的反应时间低于30 min,反应器中温度为300~600 ℃,主要生成气态和固态产物[8]。

综上所述,经过上述4种炭化反应制备的生物炭,均可作为土壤改良剂应用于土壤强化修复。4种炭化反应中,热解炭化是有机污染土壤热处理过程中最可能发生的炭化行为。水热炭化能将有机污染物转化为土壤中的腐殖酸类物质,其温和的反应条件或许能为高水分污染土壤的处理、土壤性质的保持和降低二次污染物的排放提供新的修复思路。闪蒸炭化的反应温度处于大部分有机污染物挥发或热转化温度区间,并且其固相产物多,具有较大改善土壤性能的潜力。因此,在污染土壤热处理中可能发生热解、水热及闪蒸炭化。4种炭化在污染土壤修复方面都有辅助意义,但水热及闪蒸炭化在土壤热处理过程中发生的可能性还应进一步展开理论研究和实验验证。

-

土壤热处理过程中有机污染物的炭化过程、炭化反应、炭化机理等相关研究,已有少量文献报道,涉及的污染物类型主要为石油烃和芳烃化合物[16-27](见表1)。

-

热解修复[16-18]和低温微波辅助修复[19]石油烃污染土壤均会发生聚合反应生成热解炭,前者修复石油烃污染物的炭化反应主要发生于400~500 ℃[28],后者主要发生在200 ℃以上[19]。热解炭的形成标志着土壤中有机污染物转变为稳定且无害的炭。此外,热处理过程中石油主要成分(饱和烃、芳香烃、胶质和沥青质)通过蒸发、裂解和聚合/炭化3种方式发生不同程度的转化。其中,饱和烃以气体或热解油形式转化,芳香烃聚合成更大的结构即热解油或少部分残炭,胶质和沥青质可能发生裂解、聚合(主要作用)及裂解-聚合反应形成大部分残炭[20]。另外,氧的存在会影响热解产物的分配比及性能,燃料油污染土壤在N2和CO2这2种热处理环境下,热解气、热解油和热解炭的总质量平衡比分别为60∶33.4∶5.6和70.2∶25.3∶4.6。氧化环境会使得炭从热解油向热解气转移,并改变所有热解产物的表面形貌[21]。

据上述文献分析可看出,对石油烃污染物炭化行为及其影响的关注较少。首先,石油烃的炭化反应与热处理方式、化合物组成和反应气氛有关,但其影响机制尚未完全明晰,缺少因果分析层面的足够理论支撑;其次,目前尚未定量石油烃的炭化产率和推测污染物的炭化路径;另外,应关注热处理过程中不同反应气氛的热解炭性能差异以及不同比例混合气氛的炭化情况,以获取修复石油烃污染土壤的最佳反应条件。

-

芳烃化合物是烃源岩、原油、煤及现代沉积物中含量仅次于饱和烃的重要有机族组分,分为常规多环芳烃、N/O/S杂环芳烃、芳香甾萜烷和脱羟基维生素E 4个系列[29]。近年来,N、O、S等杂环芳烃造成的土壤环境污染越来越受到环境治理者的关注[30-31]。从污染场地数据库获得的结果表明,杂环芳烃可能占土壤中多环芳烃总量的10%~20%[32]。因此,深化杂环芳烃基础理论研究,特别是热处理过程中的炭化行为研究,对于杂环芳烃污染土壤修复及可持续应用具有重要意义。

杂环芳烃经裂解、缩合等反应能生成焦炭,杂环芳烃的生焦趋势要显著大于其他烃类物质(烷烃、烯烃和多环芳烃等),其反应活性顺序为芴>咔唑>二苯并呋喃>苯噻吩>其他烃类[33]。芳烃聚合和分子重排是控制衍生炭结构的关键步骤,其反应的相对程度跟反应物起始结构有关,并且催化剂(促进氢转移和脱氢反应)可改变反应历程及产物性能[34],如在AlCl3催化作用下,吖啶和蒽及9,10-二氢蒽共炭化可以改善焦炭光学各向异性的发展[22]。此外,不同化合物在中间阶段的发展和炭化速率与杂原子的脱除程度和速率[23]及炭化过程中的动力学有关[24, 35]。另外,在300 ℃下,河流沉积物中PAHs会发生炭化反应转化为非挥发性产物[25],矿物基质对该反应有促进作用[26]。关于土壤中芳烃化合物的炭化研究较少,此前,本课题组开展了PAHs的聚合及炭化行为研究,分析了PAHs在气相和土壤中的热转化反应,结果显示气相中PAHs发生了去甲基、缩合及裂解反应,产生了高分子化合物,土壤表面覆盖了一层“炭膜”[27],从而证实了土壤中芳烃化合物炭化反应的发生。

芳烃化合物的炭化研究侧重于分析炭化中间过程,但炭化产率及其产物的理化特性不仅取决于中间相的发展方向,也与反应基质、反应条件及热处理技术等有关。因此,已有研究难以指导芳烃污染土壤的炭化行为影响分析。

-

生物质的炭化产物生物炭是一种土壤改良剂,对于改善土壤的理化性质和生物学特性,增加土壤肥力,提高作物产量都具有重要作用。然而,土壤有机物炭化产物对土壤再利用特性的影响研究还较少,在后续深入研究中可借鉴生物炭改良污染土壤的相关研究成果。

-

土壤热处理过程中,有机污染物在土壤表面生成的炭化产物能促进土壤再利用特性[18],可为修复有机污染土壤提供一种创新与战略手段[21]。目前,相关的研究主要集中在改善土壤理化性质和促进植物生长方面。CHEN等[36]研究了炭化土壤去除Cr(VI)的能力,结果表明反应温度200 ℃时土壤炭化形成的有机碳以及反应温度大于400 ℃时形成的芳族碳,均是还原Cr(VI)的主要因素。VIDONISH等[28]研究了快速高温热解(<500 ℃)后的炭化土壤理化特性,发现其pH维持在正常范围,对植物生长没有任何不良影响。此外,炭化土壤的孔隙率、持水能力和渗透性等都得到了提高,且植物生产量也高于污染土壤[16-17, 37]。以上研究证实了热处置土壤的炭化产物会影响土壤生态价值,但尚缺乏针对有机污染物炭化产物对土壤再利用特性的微观影响机制的研究,如炭化产物对热处理后土壤微生物群落的再繁殖(recolonization)及作物有效营养元素的影响机制等。

-

生物炭是生物质在厌氧或绝氧条件下,生物质经高温(240~700 ℃)裂解炭化而形成的一类高度芳香难熔性固态物质,具有良好的结构、巨大的比表面积和吸附力[38]以及高度的稳定性和抗微生物腐蚀能力[39];并且,其表面存在大量—OH,—COOH等含氧官能团,能增加土壤阳离子交换量(cation exchange capacity, CEC)[40],提高土壤对Ca2+、K+、Mg2+和

NH+4 等养分离子的吸持能力[41];还能锁定植物产生的CO2并改善低肥力土壤的质量[42]。因此,生物炭常用作土壤改良剂,其对土壤持水量、营养成分、pH和微生物菌落都有明显促进作用。1)提高土壤持水量。添加生物炭会增加土壤孔隙度,进而增加有效水含量、改善土壤持水能力[43]。与未改良土壤相比,生物炭改良土壤保留了更多水分(高达15%)[44]。随着生物炭施入量的增加,土壤毛管持水量增大,平均增加1.46倍[45]。不同材质生物炭保水能力不同,随着生物炭含量增加,施用小麦秸秆炭土壤含水量增幅最大(平均增幅28.74%),茶树枝条炭增幅最小(7.16%),不同生物炭改性土壤含水量提高范围为1.05%~55.77%[46]。

2)增加土壤营养成分。施用生物炭可增加土壤保持养分的能力和利用率,进而促进植物生长[47]。与未改良土壤相比,生物炭改良土壤有更高的CEC、比表面积、总氮[44]、有效Ca/K/P、有机碳[48]和植物生长产量[49]。炭化产物的养分保留潜力与炭化方式有关,热解炭吸附硝酸盐、铵盐和磷酸盐等养分的能力比水热炭强[50]。此外,不同含量生物炭对土壤养分的影响程度也不同。小麦根区土壤有机碳、全氮、全磷和全钾含量随生物质炭浓度(10~40 t·hm−2)的增加呈先增加后减少趋势,但均显著高于对照。其中,在20 t·hm−2生物炭浓度处理下,小麦根区土壤的有机碳、全氮和全钾达到最大[51]。

3)稳定土壤pH。我国南方地区存在大面积酸性土壤,一是由于养分有效性降低,二是由于铝离子等有毒物质毒性更强、使作物根系中毒或死亡。生物炭具有碱性,能提高酸性土壤的pH并降低土壤Al含量[48]。不同材料生物炭对土壤pH的影响幅度不同。与非豆科植物相比,豆科植物产生的生物炭对土壤pH影响更大[52],施用茶树枝条炭土壤pH增幅最大(平均增幅1.21个单位),小麦秸秆炭增幅最小(平均增幅0.41个单位)[46]。但生物炭的添加有时也能造成土壤pH降低。小麦根区土壤pH随生物含量的增加呈逐渐降低趋势,不同含量生物质炭处理下的小麦根区土壤pH均明显低于对照值[51]。这可能与原土壤理化性质和生物炭种类有关。

4)丰富土壤微生物群落。添加生物炭改良剂会影响土壤微生物数量和群落组成[39],不同生物炭对土壤生物丰度的影响有所差别。烟杆生物炭改良土壤的微生物种类增加了26.4%[53],辐射松生物炭改良土壤细菌群落丰度的时空变化>5%,包括根瘤菌(8%)、菌丝菌(14%)、链霉菌(6%)、嗜热单孢菌(8%)、链霉菌科(11%)和小单孢菌科(7%)[54]。小麦秸秆生物炭使得基因拷贝数的真菌和细菌比率降低,土壤有机碳和pH提高的同时抑制了真菌生长,土壤中菌类向着以细菌为主的微生物群落转变[55]。酵母和葡萄糖生物炭分别提高了农地和森林土壤的真菌丰度和革兰氏阴性菌丰度[56]。总之,生物炭能明显增加土壤微生物总数,其影响机制与土壤类型、土壤肥力、植物种类和生态环境等密切相关[51]。

因此,进行土壤改良时,应当考虑污染物类型、土质类型和目标改良特性等多种因素,选择合适的生物炭。生物炭对土壤性能的改良效果,汇总于表2。

-

生物炭、焦炭等焦化行业的炭化过程为人熟知,但是环保行业对有机污染土壤热处理过程的炭化过程关注不多,有机污染物炭化行为和机制尚不明晰,今后可重点从以下几个方面开展深入研究。

1)借鉴生物炭、焦炭等焦化行业的炭化成果及研究手段,加强土壤热处理过程炭化产物的多角度表征,评价炭化产物的二次污染特性,解析土壤中有机污染物的炭化行为机制。

2)探明有机土壤热处理炭化产物对土壤再利用特性的改善机制,甄别不同于生物质炭的有机污染物衍生炭影响特性,比如土壤养分、肥力、微生物、生态恢复功能等。

3)明确热处理工艺参数对土壤炭化产物的影响特性,从污染土壤修复效率与土壤再利用特性等角度综合考虑,选择面向目标需求的综合最优热脱附参数,以保持高效修复的同时,提升热处理技术的“绿色可持续修复”特性。

4)关注土壤热处理过程中其它炭化类型,探究水热炭化和闪蒸炭化对特征污染土壤热处理过程的贡献,揭示气化炭化和闪蒸炭化后的生物炭对土壤肥力的影响机制,明确多种炭化类型在不同场地特征热处理过程中发生的可能性。

5)在满足土壤修复目标前提下,探讨土壤有机物炭化行为对热处理耦合方案的影响特性,比如热-生物耦合,以及不同热处理耦合方案对土壤有机物炭化行为的影响机制。

有机污染土壤热处理过程中的炭化行为及其影响

Charring behaviors and their influence of organic contaminated soil during thermal treatment

-

摘要: 热处理技术在国内外均占有较高的市场份额,已成为有机污染场地的主要修复技术。尽管对热处理技术本身的研究和关注较多,包括工艺、参数、能源、效果、成本、应用等方面,但关于有机污染物热处理化学转化中炭化行为研究的报道并不多见。炭化行为可能会改善土壤再利用特性,对热处理工艺参数也可能有一定影响。指出了传统焦化行业中4种炭化反应类型及其机理过程,梳理了石油烃和芳烃化合物等污染土壤热处理过程中的炭化行为,总结了有机污染物炭化行为对土壤再利用特性的影响,并分析了生物质炭化产物对土壤肥力的促进机制。以此为基础,提出了有机污染土壤热处理炭化行为研究的几个重点关注方向。Abstract: Thermal treatment technologies occupy a high domestic/foreign market share, and have become the main remediation technology of organic contaminated sites. Though many studies and concerns are focused on the process, parameters, energy, effect, cost and application of thermal treatment, there are few literature reports on the charring behaviors in the thermochemical conversion of organic pollutants. The charring behaviors may improve reusability of soil and affect process parameters of thermal treatment. Four types of charring reactions and their mechanisms are shown in this paper, and the charring behaviors of petroleum hydrocarbons and aromatic compounds during thermal treatment are reviewed. The effects of organic pollutants charring on soil reusability is summarized, and the improvement of biochar to soil fertility is analysed. Based on the mentioned above, several important research topics of charring process during thermal treatment of organic contaminated soil are proposed.

-

热处理技术常用于去除石油烃 (total petroleum hydrocarbons, TPH)、多环芳烃 (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, PAHs)[1]、多氯联苯(polychlorinated biphenyls, PCBs)[2]、氯苯(chlorobenzene, CBz)[3]等土壤有机污染物。热处理技术类型的选择与污染物性质及其沸点密切相关,不同类型技术有不同的特征和适用场合(见图1)。热处理温度的高低会影响污染物的去除机制:低温热处理时,污染物主要以气相脱附(物理挥发)的形式去除;高温热处理时,污染物则以缩合转化(炭化)、氧化(燃烧)等热反应形式转移[4]。土壤热处理技术快速、高效、彻底、可控,但是有学者担忧会改变土壤结构和性质[5],破坏有机质[6]和微生物菌群[7],从而可能影响再利用特性。关于热处理中有机污染物的化学转化,特别是炭化行为,文献报道并不多见。本文将探讨、分析热处理过程中的炭化行为、炭化机理及其对土壤再利用特性的影响,以期为土壤热处理技术的科学研究与工程实践提供参考。

1. 焦化行业炭化反应类型及基本原理

传统焦化行业的炭化反应主要包括热解炭化(pyrolysis)、水热炭化(gasification)、气化炭化(hydrothermal carbonization)和闪蒸炭化(flash carbonization)4类[8],其机理、原料及反应条件各不相同(见图2)。

1)热解炭化。热解炭化的温度范围为200~3 000 ℃,其反应过程分为传统炭化I(环化及芳构化)、传统炭化II(固相聚集及芳香族平面的成长)和石墨化炭化III(三度结构增加及晶体成长)3个阶段[9],如图3所示。热解炭化以反应时间分为慢速热解和快速热解;以加热方法分为燃料燃烧、电加热和微波热解[8];以炭化所处相态分为气相炭化、液相炭化和固相炭化[9]。土壤高温热处理过程中发生的有机污染物炭化行为主要属于热解炭化的第一阶段——传统炭化I。

2)水热炭化。水热炭化是以水为介质,将原料置于密闭的水热反应釜中,于150~350 ℃停留1 h以上,最终转化为水热炭,是一种脱水脱羧的加速煤化过程[10]。水热炭化反应经历了水解、脱水、脱羧、芳香化、缩聚等步骤[11],其低温环境导致产生的气体产量非常低,大部分原料转为棕色的煤或溶解在液体中[12]。水热技术可作为重金属(如铅、铯等)污染土壤的一种可靠修复方法[13-14],还可将生物质转化为黄腐酸和腐殖酸,从而用于土壤修复[15]。

3)气化炭化。在气化炭化过程中,在大气压或高压下,生物质在温度为800 ℃左右的气化室被部分氧化。该过程的主要产品是气体,仅形成少量焦炭和液体(炭化的结果)。气化炭化与热解炭化的主要区别在于前者转化环境需要部分氧气,而后者几乎没有氧气[8]。

4)闪蒸炭化。在压力为1~2 MPa下,从原料填充床的底部点火,火势通过炭化床向上流动,阻挡工艺中向下流动的空气。燃烧每千克原料总共约有0.8~1.5 kg空气被输送至反应器中。该方法的反应时间低于30 min,反应器中温度为300~600 ℃,主要生成气态和固态产物[8]。

综上所述,经过上述4种炭化反应制备的生物炭,均可作为土壤改良剂应用于土壤强化修复。4种炭化反应中,热解炭化是有机污染土壤热处理过程中最可能发生的炭化行为。水热炭化能将有机污染物转化为土壤中的腐殖酸类物质,其温和的反应条件或许能为高水分污染土壤的处理、土壤性质的保持和降低二次污染物的排放提供新的修复思路。闪蒸炭化的反应温度处于大部分有机污染物挥发或热转化温度区间,并且其固相产物多,具有较大改善土壤性能的潜力。因此,在污染土壤热处理中可能发生热解、水热及闪蒸炭化。4种炭化在污染土壤修复方面都有辅助意义,但水热及闪蒸炭化在土壤热处理过程中发生的可能性还应进一步展开理论研究和实验验证。

2. 土壤热处理过程中有机污染物的炭化行为

土壤热处理过程中有机污染物的炭化过程、炭化反应、炭化机理等相关研究,已有少量文献报道,涉及的污染物类型主要为石油烃和芳烃化合物[16-27](见表1)。

表 1 热处理过程中有机污染物的炭化反应过程相关研究情况Table 1. Related research on charring reaction of organic pollutants during thermal treatment序号 污染物 反应基质 污染物浓度/(mg·kg−1) 热处理温度/℃ 热处理时间/min 反应气氛 载气流速/(L·min−1) 去除效率/% 炭化产物 文献 1 原油 模拟土壤 − 300~400 30~60 N2 − − char [16] 2 柴油 模拟土壤 6 271 100~350 5~120 N2 1.2 28~99 carbon [17] 3 TPH 实际土壤 16 000, 19 000 420 180 N2 1 >99.98, >98.47 char [18] 4 TPH 实际土壤 95 300 80~300 20 − − 40~99.52 char [19] 5 TPH 实际土壤 49 500 250~600 0.5, 30 N2 0.2 >67.3 char [20] 6 燃料油 模拟土壤 − 30~900 <80 CO2 0.5 − char [21] 7 杂环芳烃 − − 100~350 <120 Ar − − coke [22] 8 硫杂环芳烃 − − ≤600 <120 Ar − − coke [23] 9 蒽 − − 440~480 30~360 − − − mesophase [24] 10 菲 − − 540~560 60~300 − − − mesophase [24] 11 PAHs 河流沉积物 − 300 60 He − 95 char [25-26] 12 甲基萘 模拟土壤 40 000 200~400 10~120 N2 0.1~0.38 85.08 char [27] 注:−为文中无准确信息;“char”和“coke”表示“焦炭”,“carbon” 表示“碳”,“mesophase” 表示“液晶”。液晶指从液相到固相变化系统中间生成的中间相。 2.1 石油烃的炭化行为

热解修复[16-18]和低温微波辅助修复[19]石油烃污染土壤均会发生聚合反应生成热解炭,前者修复石油烃污染物的炭化反应主要发生于400~500 ℃[28],后者主要发生在200 ℃以上[19]。热解炭的形成标志着土壤中有机污染物转变为稳定且无害的炭。此外,热处理过程中石油主要成分(饱和烃、芳香烃、胶质和沥青质)通过蒸发、裂解和聚合/炭化3种方式发生不同程度的转化。其中,饱和烃以气体或热解油形式转化,芳香烃聚合成更大的结构即热解油或少部分残炭,胶质和沥青质可能发生裂解、聚合(主要作用)及裂解-聚合反应形成大部分残炭[20]。另外,氧的存在会影响热解产物的分配比及性能,燃料油污染土壤在N2和CO2这2种热处理环境下,热解气、热解油和热解炭的总质量平衡比分别为60∶33.4∶5.6和70.2∶25.3∶4.6。氧化环境会使得炭从热解油向热解气转移,并改变所有热解产物的表面形貌[21]。

据上述文献分析可看出,对石油烃污染物炭化行为及其影响的关注较少。首先,石油烃的炭化反应与热处理方式、化合物组成和反应气氛有关,但其影响机制尚未完全明晰,缺少因果分析层面的足够理论支撑;其次,目前尚未定量石油烃的炭化产率和推测污染物的炭化路径;另外,应关注热处理过程中不同反应气氛的热解炭性能差异以及不同比例混合气氛的炭化情况,以获取修复石油烃污染土壤的最佳反应条件。

2.2 芳烃化合物的炭化行为

芳烃化合物是烃源岩、原油、煤及现代沉积物中含量仅次于饱和烃的重要有机族组分,分为常规多环芳烃、N/O/S杂环芳烃、芳香甾萜烷和脱羟基维生素E 4个系列[29]。近年来,N、O、S等杂环芳烃造成的土壤环境污染越来越受到环境治理者的关注[30-31]。从污染场地数据库获得的结果表明,杂环芳烃可能占土壤中多环芳烃总量的10%~20%[32]。因此,深化杂环芳烃基础理论研究,特别是热处理过程中的炭化行为研究,对于杂环芳烃污染土壤修复及可持续应用具有重要意义。

杂环芳烃经裂解、缩合等反应能生成焦炭,杂环芳烃的生焦趋势要显著大于其他烃类物质(烷烃、烯烃和多环芳烃等),其反应活性顺序为芴>咔唑>二苯并呋喃>苯噻吩>其他烃类[33]。芳烃聚合和分子重排是控制衍生炭结构的关键步骤,其反应的相对程度跟反应物起始结构有关,并且催化剂(促进氢转移和脱氢反应)可改变反应历程及产物性能[34],如在AlCl3催化作用下,吖啶和蒽及9,10-二氢蒽共炭化可以改善焦炭光学各向异性的发展[22]。此外,不同化合物在中间阶段的发展和炭化速率与杂原子的脱除程度和速率[23]及炭化过程中的动力学有关[24, 35]。另外,在300 ℃下,河流沉积物中PAHs会发生炭化反应转化为非挥发性产物[25],矿物基质对该反应有促进作用[26]。关于土壤中芳烃化合物的炭化研究较少,此前,本课题组开展了PAHs的聚合及炭化行为研究,分析了PAHs在气相和土壤中的热转化反应,结果显示气相中PAHs发生了去甲基、缩合及裂解反应,产生了高分子化合物,土壤表面覆盖了一层“炭膜”[27],从而证实了土壤中芳烃化合物炭化反应的发生。

芳烃化合物的炭化研究侧重于分析炭化中间过程,但炭化产率及其产物的理化特性不仅取决于中间相的发展方向,也与反应基质、反应条件及热处理技术等有关。因此,已有研究难以指导芳烃污染土壤的炭化行为影响分析。

3. 炭化产物对土壤再利用特性的促进作用

生物质的炭化产物生物炭是一种土壤改良剂,对于改善土壤的理化性质和生物学特性,增加土壤肥力,提高作物产量都具有重要作用。然而,土壤有机物炭化产物对土壤再利用特性的影响研究还较少,在后续深入研究中可借鉴生物炭改良污染土壤的相关研究成果。

3.1 土壤有机污染物炭化产物的促进作用

土壤热处理过程中,有机污染物在土壤表面生成的炭化产物能促进土壤再利用特性[18],可为修复有机污染土壤提供一种创新与战略手段[21]。目前,相关的研究主要集中在改善土壤理化性质和促进植物生长方面。CHEN等[36]研究了炭化土壤去除Cr(VI)的能力,结果表明反应温度200 ℃时土壤炭化形成的有机碳以及反应温度大于400 ℃时形成的芳族碳,均是还原Cr(VI)的主要因素。VIDONISH等[28]研究了快速高温热解(<500 ℃)后的炭化土壤理化特性,发现其pH维持在正常范围,对植物生长没有任何不良影响。此外,炭化土壤的孔隙率、持水能力和渗透性等都得到了提高,且植物生产量也高于污染土壤[16-17, 37]。以上研究证实了热处置土壤的炭化产物会影响土壤生态价值,但尚缺乏针对有机污染物炭化产物对土壤再利用特性的微观影响机制的研究,如炭化产物对热处理后土壤微生物群落的再繁殖(recolonization)及作物有效营养元素的影响机制等。

3.2 生物质炭化产物的促进作用

生物炭是生物质在厌氧或绝氧条件下,生物质经高温(240~700 ℃)裂解炭化而形成的一类高度芳香难熔性固态物质,具有良好的结构、巨大的比表面积和吸附力[38]以及高度的稳定性和抗微生物腐蚀能力[39];并且,其表面存在大量—OH,—COOH等含氧官能团,能增加土壤阳离子交换量(cation exchange capacity, CEC)[40],提高土壤对Ca2+、K+、Mg2+和

NH+4 1)提高土壤持水量。添加生物炭会增加土壤孔隙度,进而增加有效水含量、改善土壤持水能力[43]。与未改良土壤相比,生物炭改良土壤保留了更多水分(高达15%)[44]。随着生物炭施入量的增加,土壤毛管持水量增大,平均增加1.46倍[45]。不同材质生物炭保水能力不同,随着生物炭含量增加,施用小麦秸秆炭土壤含水量增幅最大(平均增幅28.74%),茶树枝条炭增幅最小(7.16%),不同生物炭改性土壤含水量提高范围为1.05%~55.77%[46]。

2)增加土壤营养成分。施用生物炭可增加土壤保持养分的能力和利用率,进而促进植物生长[47]。与未改良土壤相比,生物炭改良土壤有更高的CEC、比表面积、总氮[44]、有效Ca/K/P、有机碳[48]和植物生长产量[49]。炭化产物的养分保留潜力与炭化方式有关,热解炭吸附硝酸盐、铵盐和磷酸盐等养分的能力比水热炭强[50]。此外,不同含量生物炭对土壤养分的影响程度也不同。小麦根区土壤有机碳、全氮、全磷和全钾含量随生物质炭浓度(10~40 t·hm−2)的增加呈先增加后减少趋势,但均显著高于对照。其中,在20 t·hm−2生物炭浓度处理下,小麦根区土壤的有机碳、全氮和全钾达到最大[51]。

3)稳定土壤pH。我国南方地区存在大面积酸性土壤,一是由于养分有效性降低,二是由于铝离子等有毒物质毒性更强、使作物根系中毒或死亡。生物炭具有碱性,能提高酸性土壤的pH并降低土壤Al含量[48]。不同材料生物炭对土壤pH的影响幅度不同。与非豆科植物相比,豆科植物产生的生物炭对土壤pH影响更大[52],施用茶树枝条炭土壤pH增幅最大(平均增幅1.21个单位),小麦秸秆炭增幅最小(平均增幅0.41个单位)[46]。但生物炭的添加有时也能造成土壤pH降低。小麦根区土壤pH随生物含量的增加呈逐渐降低趋势,不同含量生物质炭处理下的小麦根区土壤pH均明显低于对照值[51]。这可能与原土壤理化性质和生物炭种类有关。

4)丰富土壤微生物群落。添加生物炭改良剂会影响土壤微生物数量和群落组成[39],不同生物炭对土壤生物丰度的影响有所差别。烟杆生物炭改良土壤的微生物种类增加了26.4%[53],辐射松生物炭改良土壤细菌群落丰度的时空变化>5%,包括根瘤菌(8%)、菌丝菌(14%)、链霉菌(6%)、嗜热单孢菌(8%)、链霉菌科(11%)和小单孢菌科(7%)[54]。小麦秸秆生物炭使得基因拷贝数的真菌和细菌比率降低,土壤有机碳和pH提高的同时抑制了真菌生长,土壤中菌类向着以细菌为主的微生物群落转变[55]。酵母和葡萄糖生物炭分别提高了农地和森林土壤的真菌丰度和革兰氏阴性菌丰度[56]。总之,生物炭能明显增加土壤微生物总数,其影响机制与土壤类型、土壤肥力、植物种类和生态环境等密切相关[51]。

因此,进行土壤改良时,应当考虑污染物类型、土质类型和目标改良特性等多种因素,选择合适的生物炭。生物炭对土壤性能的改良效果,汇总于表2。

表 2 生物炭对土壤性能的改良效果Table 2. Effects of biochar on improving soil properties序号 生物炭原料 炭化方式 土壤类型 生物炭含量 实验类型 生物炭对土壤性能的影响 文献 1 柳树 热解炭化 壤土 2% 盆栽实验 C、N矿化分别减少了10%和75%,pH值升高了0.17个单位,总细菌、革兰氏阴性菌和放线杆菌分别增加了28%、27%和62% [39] 2 橡树和山核桃树 热解炭化 壤土 5~20 g·kg−1 土柱实验 C含量增加了17.6%~68.8%,总N含量增加了0.6%~6.9%,含水量增加了10%~15%,CEC增加了4%~30%,比表面积增加了约18%,pH增加了约1个单位 [44] 3 花生壳 热解炭化 砂质壤土 10~60 g·kg−1 盆栽实验 毛管持水量增加了1.2~1.69倍 [45] 4 牧草秸秆、茶树枝条、果树枝条、小麦秸秆 热解炭化 山地黄壤 10~80 t·hm−2 田间实验 含水量提高1.05%~55.77%,pH 值提高0.03~1.68 个单位,微生物生物量碳含量提高10.24%~90.94% [46] 5 花生壳、松木屑 热解炭化 砂质壤土 22 t·hm−2 田间实验 CEC分别提高了15%、5% [47] 6 山核桃壳 热解炭化 砂质壤土 2% 土柱实验 Ca、K分别增加了58%和106%,C增加了11.8 g·kg−1 [48] 7 猪粪 热解炭化 沙姜黑土 0.5%~2% 盆栽实验 植物产量提高了26.50%~49.98%,氮素偏生产力提高 119.32%~162.81%,植物可溶性蛋白质和维C含量增加了33.11%~42.93%和15.16%~46.06%,硝酸盐含量降低了 17.80%~22.08% [49] 8 芒草 水热炭化 砂质壤土 100 t·hm−2 田间实验 NO−3 [50] 9 芒草 热解炭化 砂质壤土 100 t·hm−2 田间实验 NO−3 NH+4 [50] 10 农业秸秆 热解炭化 棕壤 10~40 t·hm−2 室内大田实验 含水量提高了13.92%~74.14%,pH值降低了6.61%~23.97%,TOC提高了25.41%~70.92%,TN提高了25.51%~102.04%,TK提高了33.20%~108.26%,微生物总量提高了59.62%~132.69%,细菌提高了23.53%~41.43%,真菌降低了8.33%~37.12% [51] 11 烟杆 热解炭化 红壤土 40 t·hm−2 田间实验 微生物种类提高了26.4% [53] 12 辐射松 热解炭化 砂质壤土 10% 盆栽实验 微生物活性增加了15%,细菌群落丰度的时空变化>5% [54] 13 小麦秸秆 热解炭化 砂质壤土 20 t·hm−2 田间实验 16S rRNA基因拷贝数分别增加了28%,18S rRNA基因拷贝数分别减少了35% [55] 14 小麦秸秆 热解炭化 砂质壤土 40 t·hm−2 田间实验 16S rRNA基因拷贝数分别增加了64%,18S rRNA基因拷贝数分别减少了46%,嗜甲基和嗜氢菌科丰度下降了70%,厌氧菌科丰度增加了45% [55] 15 酵母 水热炭化 农田和森林土壤 30% 温室实验 真菌增加了16%,革兰氏阳性菌和革兰氏阴性菌减少了7%~14% [56] 16 葡萄糖 水热炭化 农田和森林土壤 30% 温室实验 土壤革兰氏阴性菌和革兰氏阳性菌增加了2.1‰~4.7‰ [56] 4. 展望

生物炭、焦炭等焦化行业的炭化过程为人熟知,但是环保行业对有机污染土壤热处理过程的炭化过程关注不多,有机污染物炭化行为和机制尚不明晰,今后可重点从以下几个方面开展深入研究。

1)借鉴生物炭、焦炭等焦化行业的炭化成果及研究手段,加强土壤热处理过程炭化产物的多角度表征,评价炭化产物的二次污染特性,解析土壤中有机污染物的炭化行为机制。

2)探明有机土壤热处理炭化产物对土壤再利用特性的改善机制,甄别不同于生物质炭的有机污染物衍生炭影响特性,比如土壤养分、肥力、微生物、生态恢复功能等。

3)明确热处理工艺参数对土壤炭化产物的影响特性,从污染土壤修复效率与土壤再利用特性等角度综合考虑,选择面向目标需求的综合最优热脱附参数,以保持高效修复的同时,提升热处理技术的“绿色可持续修复”特性。

4)关注土壤热处理过程中其它炭化类型,探究水热炭化和闪蒸炭化对特征污染土壤热处理过程的贡献,揭示气化炭化和闪蒸炭化后的生物炭对土壤肥力的影响机制,明确多种炭化类型在不同场地特征热处理过程中发生的可能性。

5)在满足土壤修复目标前提下,探讨土壤有机物炭化行为对热处理耦合方案的影响特性,比如热-生物耦合,以及不同热处理耦合方案对土壤有机物炭化行为的影响机制。

-

表 1 热处理过程中有机污染物的炭化反应过程相关研究情况

Table 1. Related research on charring reaction of organic pollutants during thermal treatment

序号 污染物 反应基质 污染物浓度/(mg·kg−1) 热处理温度/℃ 热处理时间/min 反应气氛 载气流速/(L·min−1) 去除效率/% 炭化产物 文献 1 原油 模拟土壤 − 300~400 30~60 N2 − − char [16] 2 柴油 模拟土壤 6 271 100~350 5~120 N2 1.2 28~99 carbon [17] 3 TPH 实际土壤 16 000, 19 000 420 180 N2 1 >99.98, >98.47 char [18] 4 TPH 实际土壤 95 300 80~300 20 − − 40~99.52 char [19] 5 TPH 实际土壤 49 500 250~600 0.5, 30 N2 0.2 >67.3 char [20] 6 燃料油 模拟土壤 − 30~900 <80 CO2 0.5 − char [21] 7 杂环芳烃 − − 100~350 <120 Ar − − coke [22] 8 硫杂环芳烃 − − ≤600 <120 Ar − − coke [23] 9 蒽 − − 440~480 30~360 − − − mesophase [24] 10 菲 − − 540~560 60~300 − − − mesophase [24] 11 PAHs 河流沉积物 − 300 60 He − 95 char [25-26] 12 甲基萘 模拟土壤 40 000 200~400 10~120 N2 0.1~0.38 85.08 char [27] 注:−为文中无准确信息;“char”和“coke”表示“焦炭”,“carbon” 表示“碳”,“mesophase” 表示“液晶”。液晶指从液相到固相变化系统中间生成的中间相。 表 2 生物炭对土壤性能的改良效果

Table 2. Effects of biochar on improving soil properties

序号 生物炭原料 炭化方式 土壤类型 生物炭含量 实验类型 生物炭对土壤性能的影响 文献 1 柳树 热解炭化 壤土 2% 盆栽实验 C、N矿化分别减少了10%和75%,pH值升高了0.17个单位,总细菌、革兰氏阴性菌和放线杆菌分别增加了28%、27%和62% [39] 2 橡树和山核桃树 热解炭化 壤土 5~20 g·kg−1 土柱实验 C含量增加了17.6%~68.8%,总N含量增加了0.6%~6.9%,含水量增加了10%~15%,CEC增加了4%~30%,比表面积增加了约18%,pH增加了约1个单位 [44] 3 花生壳 热解炭化 砂质壤土 10~60 g·kg−1 盆栽实验 毛管持水量增加了1.2~1.69倍 [45] 4 牧草秸秆、茶树枝条、果树枝条、小麦秸秆 热解炭化 山地黄壤 10~80 t·hm−2 田间实验 含水量提高1.05%~55.77%,pH 值提高0.03~1.68 个单位,微生物生物量碳含量提高10.24%~90.94% [46] 5 花生壳、松木屑 热解炭化 砂质壤土 22 t·hm−2 田间实验 CEC分别提高了15%、5% [47] 6 山核桃壳 热解炭化 砂质壤土 2% 土柱实验 Ca、K分别增加了58%和106%,C增加了11.8 g·kg−1 [48] 7 猪粪 热解炭化 沙姜黑土 0.5%~2% 盆栽实验 植物产量提高了26.50%~49.98%,氮素偏生产力提高 119.32%~162.81%,植物可溶性蛋白质和维C含量增加了33.11%~42.93%和15.16%~46.06%,硝酸盐含量降低了 17.80%~22.08% [49] 8 芒草 水热炭化 砂质壤土 100 t·hm−2 田间实验 NO−3 [50] 9 芒草 热解炭化 砂质壤土 100 t·hm−2 田间实验 NO−3 NH+4 [50] 10 农业秸秆 热解炭化 棕壤 10~40 t·hm−2 室内大田实验 含水量提高了13.92%~74.14%,pH值降低了6.61%~23.97%,TOC提高了25.41%~70.92%,TN提高了25.51%~102.04%,TK提高了33.20%~108.26%,微生物总量提高了59.62%~132.69%,细菌提高了23.53%~41.43%,真菌降低了8.33%~37.12% [51] 11 烟杆 热解炭化 红壤土 40 t·hm−2 田间实验 微生物种类提高了26.4% [53] 12 辐射松 热解炭化 砂质壤土 10% 盆栽实验 微生物活性增加了15%,细菌群落丰度的时空变化>5% [54] 13 小麦秸秆 热解炭化 砂质壤土 20 t·hm−2 田间实验 16S rRNA基因拷贝数分别增加了28%,18S rRNA基因拷贝数分别减少了35% [55] 14 小麦秸秆 热解炭化 砂质壤土 40 t·hm−2 田间实验 16S rRNA基因拷贝数分别增加了64%,18S rRNA基因拷贝数分别减少了46%,嗜甲基和嗜氢菌科丰度下降了70%,厌氧菌科丰度增加了45% [55] 15 酵母 水热炭化 农田和森林土壤 30% 温室实验 真菌增加了16%,革兰氏阳性菌和革兰氏阴性菌减少了7%~14% [56] 16 葡萄糖 水热炭化 农田和森林土壤 30% 温室实验 土壤革兰氏阴性菌和革兰氏阳性菌增加了2.1‰~4.7‰ [56] -

[1] 赵涛, 马刚平, 周宇, 等. 多环芳烃类污染土壤热脱附修复技术应用研究[J]. 环境工程, 2017, 35(11): 178-181. [2] LIU J, ZHANG H, YAO Z, et al. Thermal desorption of PCBs contaminated soil with calcium hydroxide in a rotary kiln[J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 220: 1041-1046. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.01.031 [3] 蒋村, 孟宪荣, 施维林, 等. 氯苯污染土壤低温原位热脱附修复[J]. 环境工程学报, 2019, 13(7): 1720-1726. [4] 焦文涛, 韩自玉, 吕正勇, 等. 土壤电阻加热技术原位修复有机污染土壤的关键问题与展望[J]. 环境工程学报, 2019, 13(9): 2027-2036. [5] VIDONISH J E, ZYGOURAKIS K, MASIELLO C A, et al. Thermal treatment of hydrocarbon-impacted soils: A review of technology innovation for sustainable remediation[J]. Engineering, 2016, 2(4): 426-437. doi: 10.1016/J.ENG.2016.04.005 [6] KIERSCH K, KRUSE J, REGIER T Z, et al. Temperature resolved alteration of soil organic matter composition during laboratory heating as revealed by C and N XANES spectroscopy and Py-FIMS[J]. Thermochimica Acta, 2012, 537: 36-43. [7] BÁRCENAS-MORENO G, BÅÅTH E. Bacterial and fungal growth in soil heated at different temperatures to simulate a range of fire intensities[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2009, 41(12): 2517-2526. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.09.010 [8] MEYER S, GLASER B, QUICKER P. Technical, economical, and climate-related aspects of biochar production technologies: A literature review[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(22): 9473-9483. [9] 蒋文忠. 炭素工艺学[M]. 北京: 冶金工业出版社, 2009. [10] 刘亦陶, 魏佳, 李军. 废弃生物质水热炭化技术及其产物在废水处理中的应用进展[J]. 化学与生物工程, 2019, 36(1): 1-10. [11] 吴倩芳, 张付申. 水热炭化废弃生物质的研究进展[J]. 环境污染与防治, 2012, 34(7): 70-75. [12] MALGHANI S, JÜSCHKE E, BAUMERT J, et al. Carbon sequestration potential of hydrothermal carbonization char (hydrochar) in two contrasting soils; results of a 1-year field study[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2015, 51(1): 123-134. doi: 10.1007/s00374-014-0980-1 [13] ISLAM M N, PARK J. Immobilization and reduction of bioavailability of lead in shooting range soil through hydrothermal treatment[J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2017, 191: 172-178. [14] CHEN Y, JING Z, CAI K, et al. Hydrothermal conversion of Cs-polluted soil into pollucite for Cs immobilization[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2018, 336: 503-509. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.11.187 [15] YANG F, ZHANG S, CHENG K, et al. A hydrothermal process to turn waste biomass into artificial fulvic and humic acids for soil remediation[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 686: 1140-1151. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.045 [16] KANG C, KIM D, KHAN M A, et al. Pyrolytic remediation of crude oil-contaminated soil[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 713: 136498. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136498 [17] REN J, SONG X, DING D. Sustainable remediation of diesel-contaminated soil by low temperature thermal treatment: Improved energy efficiency and soil reusability[J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 241: 124952. [18] VIDONISH J E, ZYGOURAKIS K, MASIELLO C A, et al. Pyrolytic treatment and fertility enhancement of soils contaminated with heavy hydrocarbons[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(5): 2498-2506. [19] LUO H, WANG H, KONG L, et al. Insights into oil recovery, soil rehabilitation and low temperature behaviors of microwave-assisted petroleum-contaminated soil remediation[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2019, 377: 341-348. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.05.092 [20] LI D, XU W, MU Y, et al. Remediation of petroleum-contaminated soil and simultaneous recovery of oil by fast pyrolysis[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(9): 5330-5338. [21] LEE T, NAM I, KIM J, et al. The enhanced thermolysis of heavy oil contaminated soil using CO2 for soil remediation and energy recovery[J]. Journal of CO2 Utilization, 2018, 28: 367-373. doi: 10.1016/j.jcou.2018.10.017 [22] MOCHIDA I, ANDO T, MAEDA K, et al. Catalytic carbonization of aromatic hydrocarbons: X: Cocarbonization of heterocyclic compounds with anthracene and 9, 10-dihydroanthracene catalyzed by aluminium chloride[J]. Carbon, 1980, 18(5): 319-328. doi: 10.1016/0008-6223(80)90003-2 [23] MOCHIDA I, ANDO T, MAEDA K, et al. Catalytic carbonization of aromatic hydrocarbons: IX: Carbonization mechanism of heterocyclic sulfur compounds leading to the anisotropic coke[J]. Carbon, 1980, 18(2): 131-136. doi: 10.1016/0008-6223(80)90021-4 [24] SASAKI T, JENKINS R G, ESER S, et al. Carbonization of anthracene and phenanthrene. I. Kinetics and mesophase development[J]. Energy & Fuels, 1993, 7(6): 1039-1046. [25] KOPINKE F, REMMLER M. Reactions of hydrocarbons during thermodesorption from sediments[J]. Thermochimica Acta, 1995, 263: 123-139. doi: 10.1016/0040-6031(94)02419-O [26] REMMLER M, KOPINKE F. Thermal conversion of hydrocarbons on solid matrices[J]. Thermochimica Acta, 1995, 263: 113-121. doi: 10.1016/0040-6031(94)02420-S [27] HE L, SANG Y, YU W, et al. Polymerization and carbonization behaviors of 2-methylnaphthalene in contaminated soil during thermal desorption[J]. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 2020, 231(10): 1-10. [28] VIDONISH J E, ALVAREZ P J, ZYGOURAKIS K. Pyrolytic remediation of oil-contaminated soils: Reaction mechanisms, soil changes, and implications for treated soil fertility[J]. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2018, 57(10): 3489-3500. [29] 马军, 李水福, 胡守志, 等. 芳烃化合物组成及其在油气地球化学中的应用[J]. 地质科技情报, 2010, 29(6): 73-79. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-7849.2010.06.012 [30] TIAN Z, VILA J, WANG H, et al. Diversity and abundance of high-molecular-weight azaarenes in PAH-contaminated environmental samples[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(24): 14047-14054. [31] CHIBWE L, MANZANO C A, MUIR D, et al. Deposition and source identification of nitrogen heterocyclic polycyclic aromatic compounds in snow, sediment, and air samples from the Athabasca oil sands region[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(6): 2981-2989. [32] IDOWU O, SEMPLE K T, RAMADASS K, et al. Analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their polar derivatives in soils of an industrial heritage city of Australia[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 699: 134303. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134303 [33] 仝配配, 王子军. 石油加工过程中焦炭形成的原因、类型及影响因素[J]. 化工进展, 2016, 35(S1): 101-108. [34] GUISNET M, MAGNOUX P. Organic chemistry of coke formation[J]. Applied Catalysis A: General, 2001, 212(1): 83-96. [35] SASAKI T, JENKINS R G, ESER S, et al. Carbonization of anthracene and phenanthrene. 2. Spectroscopy and mechanisms[J]. Energy & Fuels, 1993, 7(6): 1047-1053. [36] CHEN K Y, LIU J C, CHIANG P N, et al. Chromate removal as influenced by the structural changes of soil components upon carbonization at different temperatures[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2012, 162: 151-158. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.10.036 [37] LIU Y, ZHANG Q, WU B, et al. Hematite-facilitated pyrolysis: An innovative method for remediating soils contaminated with heavy hydrocarbons[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 383: 121165. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121165 [38] CHEN L, ZHANG Q, YANG X, et al. Research progress of biochar in soil restoration of lead and cadmium composite contaminated soil[J]. Hans Journal of Soil Science, 2018, 6(4): 108-114. [39] PRAYOGO C, JONES J E, BAEYENS J, et al. Impact of biochar on mineralisation of C and N from soil and willow litter and its relationship with microbial community biomass and structure[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2014, 50(4): 695-702. doi: 10.1007/s00374-013-0884-5 [40] 王典, 张祥, 姜存仓, 等. 生物质炭改良土壤及对作物效应的研究进展[J]. 中国生态农业学报, 2012, 20(8): 963-967. [41] 袁金华, 徐仁扣. 生物质炭的性质及其对土壤环境功能影响的研究进展[J]. 生态环境学报, 2011, 20(4): 779-785. [42] EVANGELOU M W H, BREM A, UGOLINI F, et al. Soil application of biochar produced from biomass grown on trace element contaminated land[J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2014, 146: 100-106. [43] KINNEY T J, MASIELLO C A, DUGAN B, et al. Hydrologic properties of biochars produced at different temperatures[J]. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2012, 41: 34-43. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.01.033 [44] LAIRD D A, FLEMING P, DAVIS D D, et al. Impact of biochar amendments on the quality of a typical Midwestern agricultural soil[J]. Geoderma, 2010, 158(3): 443-449. [45] 勾芒芒, 屈忠义. 土壤中施用生物炭对番茄根系特征及产量的影响[J]. 生态环境学报, 2013, 22(8): 1348-1352. [46] 王成己, 王义祥, 刘岑薇, 等. 不同材料生物质炭施用对果园土壤性状及活性有机碳的影响[J]. 福建农业科技, 2019(3): 66-70. [47] GASKIN J W, SPEIR A, MORRIS L M, et al. Potential for pyrolysis char to affect soil moisture and nutrient status of a loamy sand soil, 2007[C]//2007 Georgia Water Resources Conference. Proceedings of the 2007 Georgia Water Resources Conference. University of Georgia, 2007: 1-3. [48] NOVAK J M, BUSSCHER W J, LAIRD D L, et al. Impact of biochar amendment on fertility of a southeastern coastal plain soil[J]. Soil Science, 2009, 174(2): 105-112. doi: 10.1097/SS.0b013e3181981d9a [49] 孙雪, 刘琪琪, 郭虎, 等. 猪粪生物质炭对土壤肥效及小白菜生长的影响[J]. 农业环境科学学报, 2016, 35(9): 1756-1763. [50] GRONWALD M, DON A, TIEMEYER B, et al. Effects of fresh and aged chars from pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonization on nutrient sorption in agricultural soils[J]. Soil, 2015, 1(1): 475-489. doi: 10.5194/soil-1-475-2015 [51] 郑子乔, 祝经伦. 生物质炭对小麦根区土壤养分和微生物特征的影响[J]. 水土保持研究, 2019, 26(3): 35-41. [52] YUAN J H, XU R K. The amelioration effects of low temperature biochar generated from nine crop residues on an acidic Ultisol[J]. Soil Use and Management, 2011, 27(1): 110-115. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-2743.2010.00317.x [53] 王成己, 陈庆荣, 陈曦, 等. 烟秆生物质炭对烟草根际土壤养分及细菌群落的影响[J]. 中国烟草科学, 2017, 38(1): 42-47. [54] ANDERSON C R, CONDRON L M, CLOUGH T J, et al. Biochar induced soil microbial community change: Implications for biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus[J]. Pedobiologia, 2011, 54(5/6): 309-320. [55] CHEN J, LIU X, ZHENG J, et al. Biochar soil amendment increased bacterial but decreased fungal gene abundance with shifts in community structure in a slightly acid rice paddy from Southwest China[J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 2013, 71: 33-44. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2013.05.003 [56] STEINBEISS S, GLEIXNER G, ANTONIETTI M. Effect of biochar amendment on soil carbon balance and soil microbial activity[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2009, 41(6): 1301-1310. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.03.016 -

下载:

下载: