|

[1]

|

LIU X H, LU S Y, GUO W, et al. Antibiotics in the aquatic environments: A review of lakes, China[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 627: 1195-1208. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.271

|

|

[2]

|

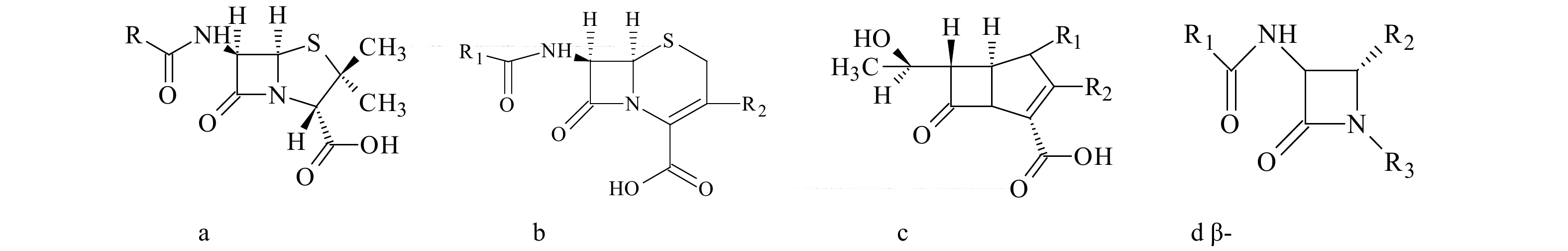

THYKAER J, NIELSEN J. Metabolic engineering of β-lactam production[J]. Metabolic Engineering, 2003, 5(1): 56-69. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7176(03)00003-X

|

|

[3]

|

HARRIS S J, CORMICAN M, CUMMINS E. Antimicrobial residues and antimicrobial-resistant bacteria: Impact on the microbial environment and risk to human health: A review[J]. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal, 2012, 18(4): 767-809. doi: 10.1080/10807039.2012.688702

|

|

[4]

|

OZCENGIZ G, DEMAIN A L. Recent advances in the biosynthesis of penicillins, cephalosporins and clavams and its regulation[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2013, 31(2): 287-311. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.12.001

|

|

[5]

|

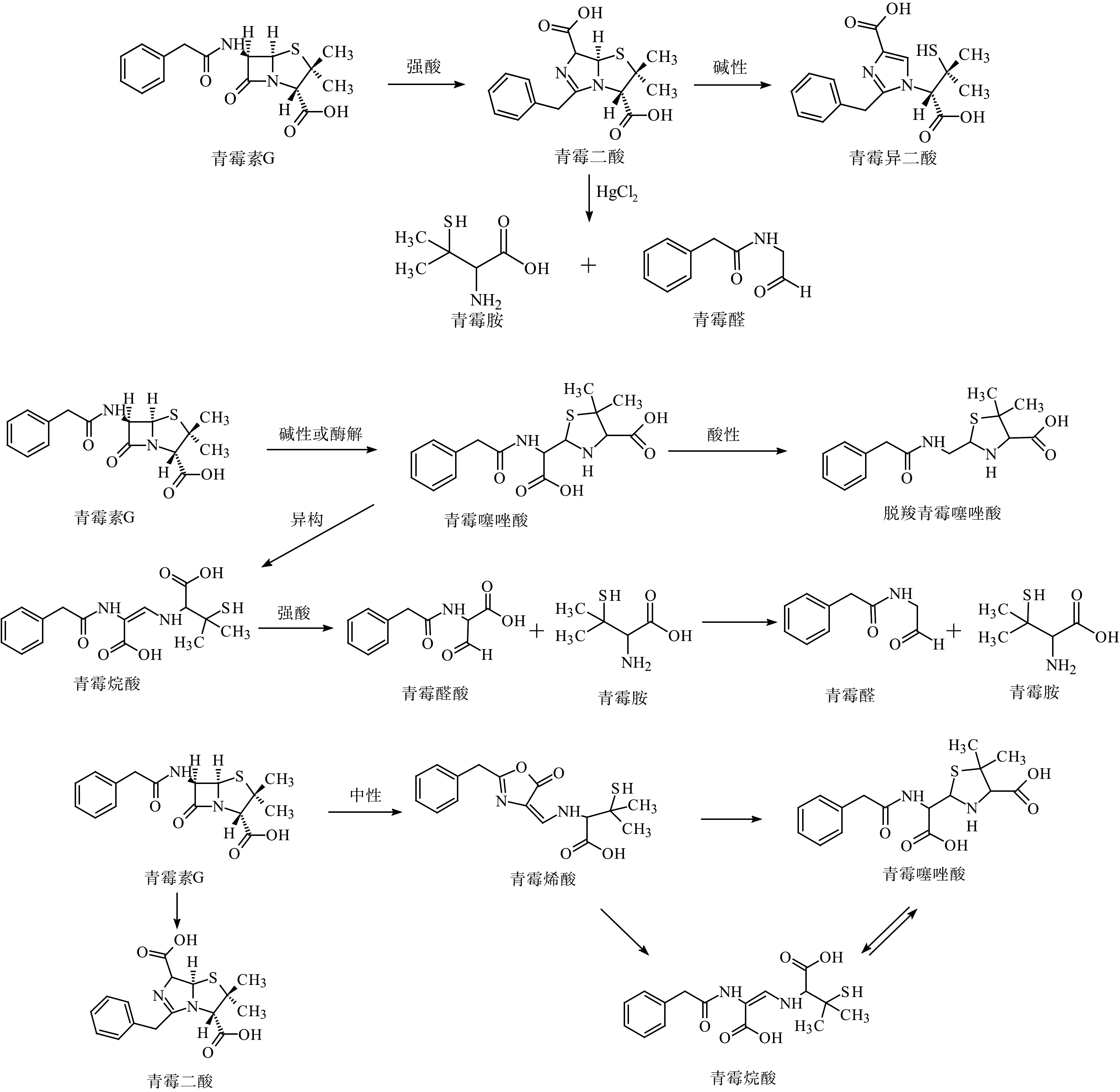

PAN M, CHU L M. Fate of antibiotics in soil and their uptake by edible crops[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 599-600: 500-512. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.214

|

|

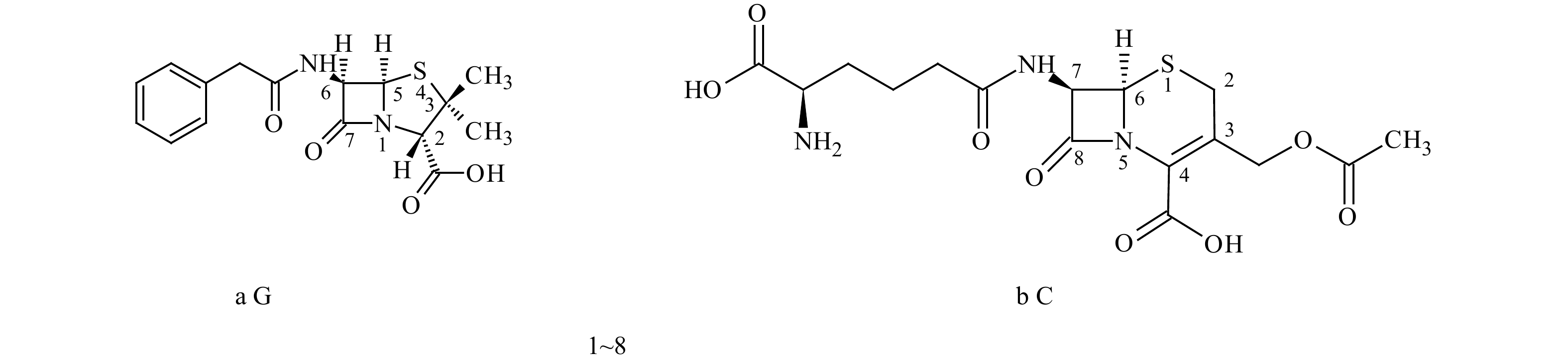

[6]

|

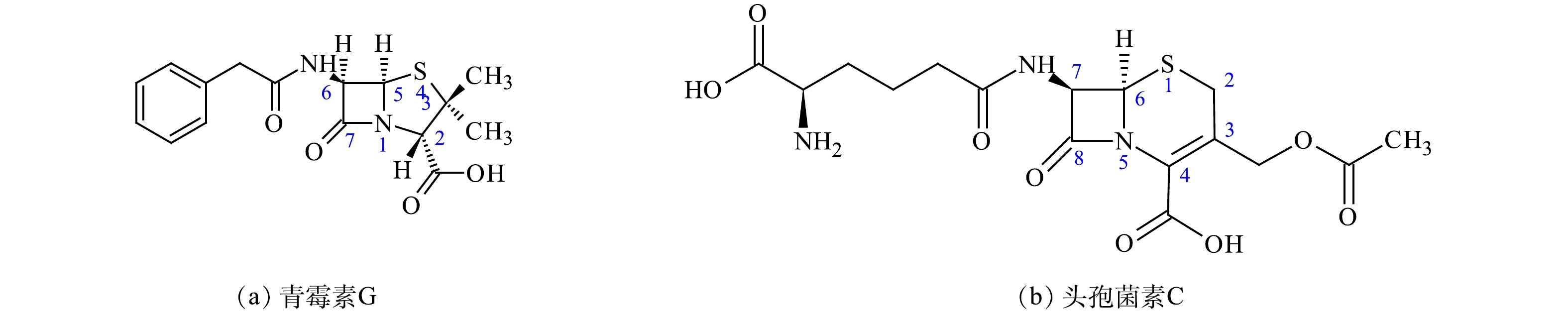

MILAKOVIC M, VESTERGAARD G, GONZALEZ-PLAZA J J, et al. Effects of industrial effluents containing moderate levels of antibiotic mixtures on the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes and bacterial community composition in exposed creek sediments[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 706: 136001. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136001

|

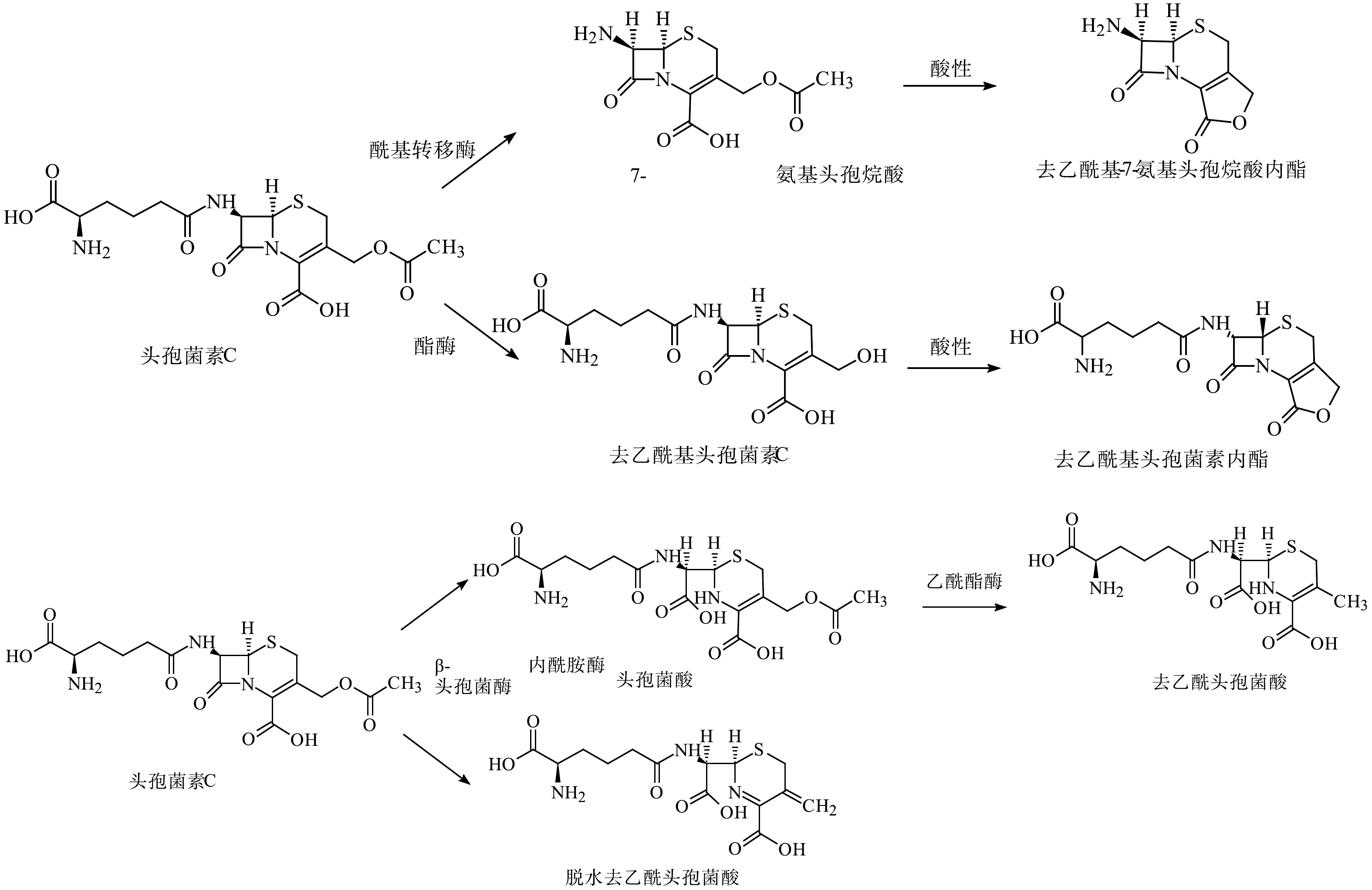

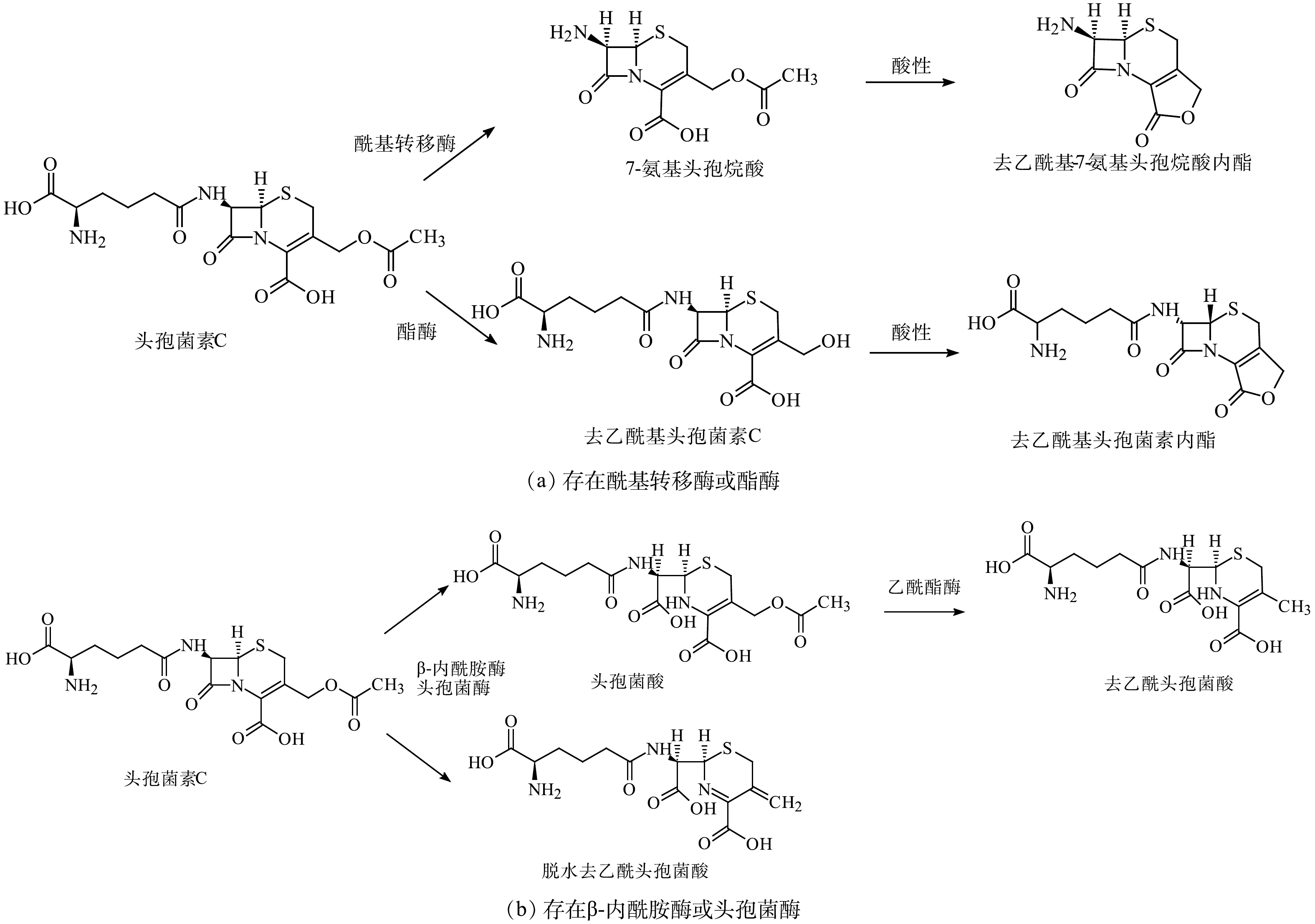

|

[7]

|

YU X, ZHANG M Y, ZUO J E, et al. Evaluation of antibiotic resistant lactose fermentative opportunistic pathogenic enterobacteriaceae bacteria and blatem-2 gene in cephalosporin wastewater and its discharge receiving river[J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2018, 228: 458-465.

|

|

[8]

|

WANG J L, MAO D Q, MU Q H, et al. Fate and proliferation of typical antibiotic resistance genes in five full-scale pharmaceutical wastewater treatment plants[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2015, 526: 366-373. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.046

|

|

[9]

|

LARSSON D G J, DE PEDRO C, PAXEUS N. Effluent from drug manufactures contains extremely high levels of pharmaceuticals[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2007, 148(3): 751-755. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.07.008

|

|

[10]

|

KOVALOVA L, SIEGRIST H, SINGER H, et al. Hospital wastewater treatment by membrane bioreactor: Performance and efficiency for organic micropollutant elimination[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(3): 1536-1545.

|

|

[11]

|

WATKINSON A J, MURBY E J, KOLPIN D W, et al. The occurrence of antibiotics in an urban watershed: From wastewater to drinking water[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2009, 407(8): 2711-2723. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.11.059

|

|

[12]

|

KUMMERER K. Drugs in the environment: Emission of drugs, diagnostic aids and disinfectants into wastewater by hospitals in relation to other sources: A review[J]. Chemosphere, 2001, 45(6/7): 957-969.

|

|

[13]

|

SLANAA M, DOLENC M S. Environmental risk assessment of antimicrobials applied in veterinary medicine: A field study and laboratory approach[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2013, 35(1): 131-141. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2012.11.017

|

|

[14]

|

PARK H, CHOUNG Y K. Degradation of antibiotics (tetracycline, sulfathiazole, ampicillin) using enzymes of glutathion s-transferase[J]. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal, 2007, 13(5): 1147-1155. doi: 10.1080/10807030701506223

|

|

[15]

|

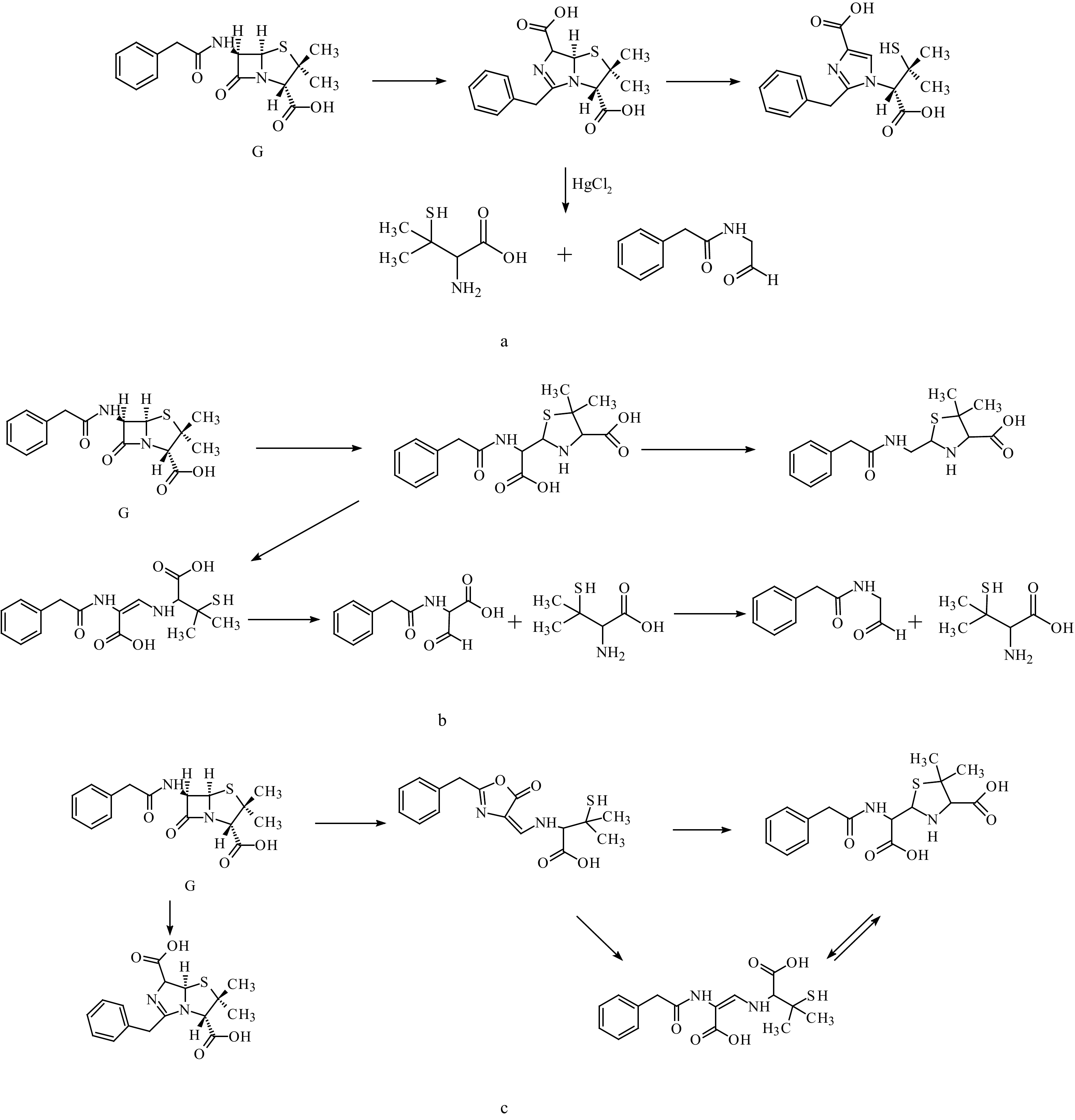

WANG B, LI G M, CAI C, et al. Assessing the safety of thermally processed penicillin mycelial dreg following the soil application: Organic matter’s maturation and antibiotic resistance genes[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 636: 1463-1469. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.288

|

|

[16]

|

CAI C, LIU H L, WANG B. Performance of microwave treatment for disintegration of cephalosporin mycelial dreg (CMD) and degradation of residual cephalosporin antibiotics[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2017, 331: 265-272. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.02.034

|

|

[17]

|

ZHANG Z H, ZHAO J, YU C G, et al. Evaluation of aerobic co-composting of penicillin fermentation fungi residue with pig manure on penicillin degradation, microbial population dynamics and composting maturity[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2015, 198: 403-409. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.09.005

|

|

[18]

|

LI D, YANG M, HU J Y, et al. Determination of penicillin g and its degradation products in a penicillin production wastewater treatment plant and the receiving river[J]. Water Research, 2008, 42(1/2): 307-317.

|

|

[19]

|

王勇军, 陈平, 韦惠民, 等. 青霉素菌渣厌氧消化技术研究[J]. 中国沼气, 2015, 33(5): 28-31. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-1166.2015.05.005

|

|

[20]

|

WANG B, LIU H L, CAI C, et al. Effect of dry mycelium of penicillium chrysogenum fertilizer on soil microbial community composition, enzyme activities and snap bean growth[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23: 20728-20738.

|

|

[21]

|

ZHANG Z H, ZHAO J, YU C G, et al. Chelatococcus composti sp. nov., isolated from penicillin fermentation fungi residue with pig manure co-compost[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017, 67(3): 565-569. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001651

|

|

[22]

|

CAI C, LIU H L. Application of microwave-pretreated cephalosporin mycelial dreg (CMD) as soil amendment: Temporal changes in chemical and fluorescent parameters of soil organic matter[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 621: 417-424. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.261

|

|

[23]

|

DESHPANDE A D, BAHETI K G, CHATTERJEE N R. Degradation of β-lactam antibiotics[J]. Current Science, 2004, 87(12): 1684-1695.

|

|

[24]

|

GUAN Y D, WANG B, GAO Y X, et al. Occurrence and fate of antibiotics in the aqueous environment and their removal by constructed wetlands in China: A review[J]. Pedosphere, 2017, 27(1): 42-51. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(17)60295-9

|

|

[25]

|

JAFARI OZUMCHELOUEI E, HAMIDIAN A H, ZHANG Y, et al. Physicochemical properties of antibiotics: A review with an emphasis on detection in the aquatic environment[J]. Water Environment Research, 2020, 92(2): 177-188. doi: 10.1002/wer.1237

|

|

[26]

|

SHEEHAN J C, HENERYLOGAN K R. The total synthesis of penicillin-V[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1959, 81(12): 1262-1263.

|

|

[27]

|

DAVIES J, DAVIES D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance[J]. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 2010, 74(3): 417-433. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10

|

|

[28]

|

NEWTON G G F, ABRAHAM E P. Cephalosporin-C, a new antibiotic containing sulphur and d-α-aminoadipic acid[J]. Nature, 1955, 175: 548-550. doi: 10.1038/175548a0

|

|

[29]

|

ABRAHAM E P, NEWTON G G F. The structure of cephalosporin C[J]. Biochemical Journal, 1961, 79: 377-391. doi: 10.1042/bj0790377

|

|

[30]

|

SONAWANE C V. Enzymatic modifications of cephalosporins by cephalosporin acylase and other enzymes[J]. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 2006, 26(2): 95-120. doi: 10.1080/07388550600718630

|

|

[31]

|

RIBEIRO A R, SURES B, SCHMIDT T C. Cephalosporin antibiotics in the aquatic environment: A critical review of occurrence, fate, ecotoxicity and removal technologies[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 241: 1153-1166. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.06.040

|

|

[32]

|

ALDEEK F, ROSANA M R, HAMILTON Z K, et al. LC-MS/MS method for the determination and quantitation of penicillin g and its metabolites in citrus fruits affected by huanglongbing[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2015, 63(26): 5993-6000. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02030

|

|

[33]

|

WANG X H, LIN A Y. Phototransformation of cephalosporin antibiotics in an aqueous environment results in higher toxicity[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(22): 12417-12426.

|

|

[34]

|

EVAGGELOPOULOU E N, SAMANIDOU V F. Development and validation of an HPLC method for the determination of six penicillin and three amphenicol antibiotics in gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) tissue according to the European Union Decision 2002/657/EC[J]. Food Chemistry, 2013, 136(3/4): 1322-1329.

|

|

[35]

|

LIN J, NISHINO K, ROBERTS M C, et al. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2015, 6: 34.

|

|

[36]

|

REN Z, ZHANG W, LI J, et al. Effect of organic solutions on the stability and extraction equilibrium of penicillin G[J]. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 2010, 55(8): 2687-2694.

|

|

[37]

|

ZENG X M, LIN J. Beta-lactamase induction and cell wall metabolism in gram-negative bacteria[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2013, 4: 128.

|

|

[38]

|

PAZDA M, KUMIRSKA J, STEPNOWSKI P, et al. Antibiotic resistance genes identified in wastewater treatment plant systems: A review[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 697: 134023. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134023

|

|

[39]

|

LI D, YANG M, HU J Y, et al. Determination and fate of oxytetracycline and related compounds in oxytetracycline production wastewater and the receiving river[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2008, 27(1): 80-86. doi: 10.1897/07-080.1

|

|

[40]

|

MICHAEL I, RIZZO L, MCARDELL C S, et al. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for the release of antibiotics in the environment: A review[J]. Water Research, 2013, 47(3): 957-995. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.11.027

|

|

[41]

|

MATSUO H, SAKAMOTO H, ARIZONO K, et al. Behavior of pharmaceuticals in waste water treatment plant in Japan[J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2011, 87(1): 31-35. doi: 10.1007/s00128-011-0299-7

|

|

[42]

|

LARSSON D G J. Pollution from drug manufacturing: Review and perspectives[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2014, 369: 20130571. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0571

|

|

[43]

|

KALTENBOECK B, RAY P, KNOWLTON K F, et al. Development and validation of a UPLC-MS/MS method to monitor cephapirin excretion in dairy cows following intramammary infusion[J]. Plos One, 2014, 9(11): e112343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112343

|

|

[44]

|

MANZETTI S, GHISI R. The environmental release and fate of antibiotics[J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2014, 79(1/2): 7-15.

|

|

[45]

|

KUMMERER K, HENNINGER A. Promoting resistance by the emission of antibiotics from hospitals and households into effluent[J]. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 2003, 9(12): 1203-1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2003.00739.x

|

|

[46]

|

KUMMERER K. Resistance in the environment[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2004, 54(2): 311-320. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh325

|

|

[47]

|

CROMWELL G L. Why and how antibiotics are used in swine production[J]. Animal Biotechnology, 2002, 13(1): 7-27. doi: 10.1081/ABIO-120005767

|

|

[48]

|

KUMMERER K. Antibiotics in the aquatic environment: A review-Part I[J]. Chemosphere, 2009, 75(4): 417-434. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.11.086

|

|

[49]

|

JECHALKE S, HEUER H, SIEMENS J, et al. Fate and effects of veterinary antibiotics in soil[J]. Trends in Microbiology, 2014, 22(9): 536-545. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.05.005

|

|

[50]

|

PAN M, CHU L M. Leaching behavior of veterinary antibiotics in animal manure-applied soils[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 579: 446-473.

|

|

[51]

|

LI S, SHI W Z, LIU W, et al. A duodecennial national synthesis of antibiotics in china's major rivers and seas (2005-2016)[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 615: 906-917. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.328

|

|

[52]

|

JIANG M X, WANG L H, JI R. Biotic and abiotic degradation of four cephalosporin antibiotics in a lake surface water and sediment[J]. Chemosphere, 2010, 80(11): 1399-1405. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.05.048

|

|

[53]

|

ZHANG Q, YING G, PAN C, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the river basins of China: Source analysis, multimedia modelling, and linkage to bacterial resistance[J]. Environmental Science Technology, 2015, 49(11): 6772-6782. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00729

|

|

[54]

|

LI B, ZHANG T. Mass flows and removal of antibiotics in two municipal wastewater treatment plants[J]. Chemosphere, 2011, 83(9): 1284-1289. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.03.002

|

|

[55]

|

HIRTE K, SEIWERT B, SCHUURMANN G, et al. New hydrolysis products of the beta-lactam antibiotic amoxicillin, their pH-dependent formation and search in municipal wastewater[J]. Water Research, 2016, 88: 880-888. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.11.028

|

|

[56]

|

CHRISTIANA T, SCHNEIDER R J, FÄRBERB H A, et al. Determination of antibiotic residues in manure, soil, and surface waters[J]. Acta Hydrochimica et Hydrobiologica, 2003, 31: 36-44. doi: 10.1002/aheh.200390014

|

|

[57]

|

WATKINSON A J, MURBY E J, COSTANZO S D. Removal of antibiotics in conventional and advanced wastewater treatment: Implications for environmental discharge and wastewater recycling[J]. Water Research, 2007, 41(18): 4164-4176. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.04.005

|

|

[58]

|

TRAN N H, REINHARD M, GIN K Y H. Occurrence and fate of emerging contaminants in municipal wastewater treatment plants from different geographical regions: A review[J]. Water Research, 2018, 133: 182-207. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.12.029

|

|

[59]

|

PUTRA E K, PRANOWO R, SUNARSO J, et al. Performance of activated carbon and bentonite for adsorption of amoxicillin from wastewater: Mechanisms, isotherms and kinetics[J]. Water Research, 2009, 43(9): 2419-2430. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.02.039

|

|

[60]

|

GULKOWSKA A, HE Y H, SO M K, et al. The occurrence of selected antibiotics in Hong Kong coastal waters[J]. Marine Pollution Bulltin, 2007, 54(8): 1287-1293. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.04.008

|

|

[61]

|

GULKOWSKA A, LEUNG HW, SO M K, et al. Removal of antibiotics from wastewater by sewage treatment facilities in Hong Kong and Shenzhen, China[J]. Water Research, 2008, 42(1/2): 395-403.

|

|

[62]

|

CHA J M, YANG S, CARLSON K H. Trace determination of β-lactam antibiotics in surface water and urban wastewater using liquid chromatography combined with electrospray tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2006, 1115(1/2): 46-57.

|

|

[63]

|

LI B, ZHANG T, XU Z Y, et al. Rapid analysis of 21 antibiotics of multiple classes in municipal wastewater using ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2009, 645(1/2): 64-72.

|

|

[64]

|

周波, 项铁男. 青霉素菌渣灭活技术研究[J]. 中国抗生素, 2014, 39(6): 418-421.

|

|

[65]

|

PAN M, CHU L M. Adsorption and degradation of five selected antibiotics in agricultural soil[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 545/546: 48-56. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.040

|

|

[66]

|

ZHANG G, MA D, PENG C, et al. Process characteristics of hydrothermal treatment of antibiotic residue for solid biofuel[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2014, 252: 230-238. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2014.04.092

|

|

[67]

|

王冉, 刘铁铮, 王恬. 抗生素在环境中的转归及其生态毒性[J]. 生态学报, 2006, 26(1): 265-270. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1000-0933.2006.01.032

|

|

[68]

|

贾励瑛. β-内酰胺类抗生素在污水处理厂的分布与迁移转化[D]. 邯郸: 河北工程大学, 2012.

|

|

[69]

|

安博宇, 袁园园, 黄玲利, 等. 头孢菌素类药物在环境中的行为及残留研究进展[J/OL]. [2020-06-03]. 中国抗生素杂志: 1-9.https://doi.org/10.13461/j.cnki.cja.006785.

|

|

[70]

|

王冰, 孙成, 胡冠九. 环境中抗生素残留潜在风险及其研究进展[J]. 环境科学与技术, 2007, 30(3): 108-112. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-6504.2007.03.040

|

|

[71]

|

MITCHELL S M, ULLMAN J L, TEEL A L, et al. pH and temperature effects on the hydrolysis of three beta-lactam antibiotics: Ampicillin, cefalotin and cefoxitin[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014: 466 547-555.

|

|

[72]

|

LANGIN A, ALEXY R, KONIG A, et al. Deactivation and transformation products in biodegradability testing of beta-lactams amoxicillin and piperacillin[J]. Chemosphere, 2009, 75(3): 347-354. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.12.032

|

|

[73]

|

KESSLER D P, GHEBRE-SELLASSIE I, M. KNEVEL A, et al A kinetic analysis of the acidic degradation of penicillin g and confirmation of penicillamine as a degradation product[J]. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2, 1981, 12(9): 1247-1251.

|

|

[74]

|

ALDEEK F, CANZANI D, STANDLAND M, et al. Identification of penicillin g metabolites under various environmental conditions using UHPLC-MS/MS[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2016, 64(31): 6100-6107. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b06150

|

|

[75]

|

陈兆坤, 胡昌勤. 头孢菌素类抗生素的降解机制[J]. 国外医药(抗生素分册), 2004, 25(6): 249-252.

|

|

[76]

|

温玉麟. 头孢菌素类抗生素的稳定性(上)[J]. 国外医药(抗生素分册), 1990, 11(4): 278-284.

|

|

[77]

|

WATKINS R R, PAPP-WALLACE K M, DRAWZ S M, et al. Novel beta-lactamase inhibitors: A therapeutic hope against the scourge of multidrug resistance[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2013, 4: 392.

|

|

[78]

|

KÜMMERER K. Antibiotics in the aquatic environment: A review-Part II[J]. Chemosphere, 2009, 75(4): 435-441. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.12.006

|

|

[79]

|

THOMSON K S, MOLAND E S. Version 2000: The new β-lactamases of gram-negative bacteria at the dawn of the new millennium[J]. Microbes and Infection, 2000, 2(10): 1225-1235. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01276-4

|

|

[80]

|

CHEN J, LI H, YANG J S, et al. Prevalence and characterization of integrons in multidrug resistant acinetobacter baumannii in eastern China: A multiple-hospital study[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2015, 12(8): 10093-10105. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120810093

|

|

[81]

|

YIGIT H, QUEENAN A M, ANDERSON G J, et al. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of klebsiella pneumoniae[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2001, 45(4): 1151-1161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1151-1161.2001

|

|

[82]

|

ADLER M. Mechanisms and dynamics of carbapenem resistance in Escherichia coli[D]. Sweden: Uppsala University, 2014.

|

|

[83]

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U S), National Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Infectious Diseases(U S), National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention(U S), National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (U S). Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013[M/OL]. [2020-06-03]. 2013. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/20705.

|

|

[84]

|

HENRIQUES I S, FONSECA F, ALVES A, et al. Occurrence and diversity of integrons and β-lactamase genes among ampicillin-resistant isolates from estuarine waters[J]. Research in Microbiology, 2006, 157(10): 938-947. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.09.003

|

|

[85]

|

BAQUERO F, MARTINEZ J L, CANTON R. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in water environments[J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2008, 19(3): 260-265. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.05.006

|

|

[86]

|

LI D, QI R, YANG M, et al. Bacterial community characteristics under long-term antibiotic selection pressures[J]. Water Research, 2011, 45(18): 6063-6073. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.09.002

|

|

[87]

|

CALL D R, MATTHEWS L, SUBBIAH M, et al. Do antibiotic residues in soils play a role in amplification and transmission of antibiotic resistant bacteria in cattle populations?[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2013, 4: 193.

|

|

[88]

|

PEI R, CHA J, CARLSON K H, et al. Response of antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) to biological treatment in dairy lagoon water[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2007, 41(14): 5108-5113.

|

|

[89]

|

罗越. 青霉素生产废水深度处理[D]. 太原: 山西大学, 2015.

|

|

[90]

|

CHEN Z Q, WANG H C, CHEN Z B, et al. Performance and model of a full-scale up-flow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) to treat the pharmaceutical wastewater containing 6-APA and amoxicillin[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2011, 185(2/3): 905-913.

|

|

[91]

|

GUO R X, XIE X D, CHEN J Q. The degradation of antibiotic amoxicillin in the Fenton-activated sludge combined system[J]. Environmental Technology, 2015, 36(5/6/7/8): 844-851.

|

|

[92]

|

ZHOU L J, YING G G, LIU S, et al. Occurrence and fate of eleven classes of antibiotics in two typical wastewater treatment plants in south China[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2013, 452/453: 365-376. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.03.010

|

|

[93]

|

BOUKI C, VENIERI D, DIAMADOPOULOS E. Detection and fate of antibiotic resistant bacteria in wastewater treatment plants: A review[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2013, 91: 1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.01.016

|

|

[94]

|

CHOW L, WALDRON L, GILLINGS M R. Potential impacts of aquatic pollutants: Sub-clinical antibiotic concentrations induce genome changes and promote antibiotic resistance[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2015, 6: 803.

|

|

[95]

|

WANG J Y, AN X L, HUANG F Y, et al. Antibiotic resistome in a landfill leachate treatment plant and effluent-receiving river[J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 242: 125207. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125207

|

|

[96]

|

张昱, 唐妹, 田哲, 等. 制药废水中抗生素的去除技术研究进展[J]. 环境工程学报, 2018, 12(1): 1-14. doi: 10.12030/j.cjee.201801010

|

|

[97]

|

成建华, 张文莉. 抗生素菌渣处理工艺设计[J]. 医药工程设计, 2003, 24(2): 31-34.

|

|

[98]

|

李再兴, 田宝阔, 左剑恶, 等. 抗生素菌渣处理处置技术进展[J]. 环境工程, 2012, 30(2): 72-75.

|

|

[99]

|

LI C, ZHANG G, ZHANG Z, et al. Alkaline thermal pretreatment at mild temperatures for biogas production from anaerobic digestion of antibiotic mycelial residue[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2016, 208: 49-57. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.02.064

|

|

[100]

|

ZHANG S H, CHEN Z Q, WEN Q X, et al. Assessing the stability in composting of penicillin mycelial dreg via parallel factor (parafac) analysis of fluorescence excitation-emission matrix (EEM)[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2016, 299: 167-176. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2016.04.020

|

|

[101]

|

ZHANG S H, CHEN Z Q, WEN Q X, et al. Effectiveness of bulking agents for co-composting penicillin mycelial dreg (PMD) and sewage sludge in pilot-scale system[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(2): 1362-1370. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5357-y

|

|

[102]

|

ZHANG S H, CHEN Z Q, WEN Q X, et al. Assessment of maturity during co-composting of penicillin mycelial dreg via fluorescence excitation-emission matrix spectra: Characteristics of chemical and fluorescent parameters of water-extractable organic matter[J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 155: 358-366. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.04.051

|

|

[103]

|

YANG L, ZHANG S H, CHEN Z Q, et al. Maturity and security assessment of pilot-scale aerobic co-composting of penicillin fermentation dregs (PFDs) with sewage sludge[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2016, 204: 185-191. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.01.004

|

|

[104]

|

AWAD M, TIAN Z, GAO Y X, et al. Pretreatment of spiramycin fermentation residue using hyperthermophilic digestion: Quick startup and performance[J]. Water Science and Technology, 2018, 78(9): 1823-1832. doi: 10.2166/wst.2018.256

|

|

[105]

|

NAZARI G, ABOLGHASEMI H, ESMAIELI M, et al. Aqueous phase adsorption of cephalexin by walnut shell-based activated carbon: A fixed-bed column study[J]. Applied Surface Science, 2016, 375: 144-153. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.03.096

|

|

[106]

|

MITCHELL S M, SUBBIAH M, ULLMAN J L, et al. Evaluation of 27 different biochars for potential sequestration of antibiotic residues in food animal production environments[J]. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2015, 3(1): 162-169. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2014.11.012

|

|

[107]

|

HE X, MEZYK S P, MICHAEL I, et al. Degradation kinetics and mechanism of beta-lactam antibiotics by the activation of H2O2 and Na2S2O8 under UV-254 nm irradiation[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2014, 279: 375-383. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.07.008

|

|

[108]

|

SERNA-GALVIS E A, FERRARO F, SILVA-AGREDO J, et al. Degradation of highly consumed fluoroquinolones, penicillins and cephalosporins in distilled water and simulated hospital wastewater by UV254 and UV254/persulfate processes[J]. Water Research, 2017, 122: 128-138. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.05.065

|

|

[109]

|

岳秀萍, 张涛. Fenton氧化与Fe/C微电解预处理头孢菌抗生素废水的实验研究[J]. 太原理工大学学报, 2012, 43(3): 325-328. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-9432.2012.03.018

|

|

[110]

|

NAVALON S, ALVARO M, GARCIA H. Reaction of chlorine dioxide with emergent water pollutants: Product study of the reaction of three β-lactam antibiotics with ClO2[J]. Water Research, 2008, 42(8/9): 1935-1942.

|

|

[111]

|

ARSLAN-ALATON I, DOGRUEL S. Pre-treatment of penicillin formulation effluent by advanced oxidation processes[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2004, 112(1/2): 105-113.

|

|

[112]

|

ELMOLLA E, CHAUDHURI M. Optimization of fenton process for treatment of amoxicillin, ampicillin and cloxacillin antibiotics in aqueous solution[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2009, 170(2/3): 666-672.

|

|

[113]

|

KLAUSON D, BABKINA J, STEPANOVA K, et al. Aqueous photocatalytic oxidation of amoxicillin[J]. Catalysis Today, 2010, 151(1/2): 39-45.

|

|

[114]

|

ELMOLLA ES, CHAUDHURI M. Degradation of the antibiotics amoxicillin, ampicillin and cloxacillin in aqueous solution by the photo-Fenton process[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2009, 172(2/3): 1476-1481.

|

|

[115]

|

ANDREOZZI R, CANTERINO M, MAROTTA R, et al. Antibiotic removal from wastewaters: The ozonation of amoxicillin[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2005, 122(3): 243-250. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.03.004

|

|

[116]

|

ARSLAN-ALATON I, CAGLAYAN A E. Toxicity and biodegradability assessment of raw and ozonated procaine penicillin G formulation effluent[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2006, 63(1): 131-140. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2005.02.014

|

|

[117]

|

DODD M C, BUFFLE M O, GUNTEN U V. Oxidation of antibacterial molecules by aqueous ozone: Moiety-specific reaction kinetics and application to ozone-based wastewater treatment[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2006, 40(6): 1969-1977.

|

|

[118]

|

YI Q Z, GAO Y X, ZHANG H, et al. Establishment of a pretreatment method for tetracycline production wastewater using enhanced hydrolysis[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2016, 300: 139-145. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2016.04.120

|

|

[119]

|

YI Q Z, ZHANG Y, GAO Y X, et al. Anaerobic treatment of antibiotic production wastewater pretreated with enhanced hydrolysis: Simultaneous reduction of COD and ARGs[J]. Water Research, 2017, 110: 211-217. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.12.020

|

DownLoad:

DownLoad: