氯化石蜡(chlorinated paraffins, CPs)是一系列多氯正构烷烃的复杂混合物,由正构烷烃和分子氯在紫外线、高温或高压条件下发生自由取代反应产生,一般氯含量(质量分数)在30%~70%之间[1]。根据碳链长度CPs通常被分为三大类,C10~13的为短链氯化石蜡(short chain chlorinated paraffins, SCCPs);C14~17的为中链氯化石蜡(medium chain chlorinated paraffins, MCCPs);C≥18的为长链氯化石蜡(long chain chlorinated paraffins, LCCPs)。此外,还存在C6~9的超短链氯化石蜡(very short chain chlorinated paraffins, vSCCPs),被认为是SCCPs的加工副产品[2],或是由SCCPs和MCCPs降解而产生[3]。

20世纪30年代,CPs已经在全球范围内开始生产,主要用作增塑剂、阻燃剂、金属加工液和皮革加脂剂等[4-5]。我国自20世纪50年代末开始生产CPs,2019年总产能已超过200万t·a-1,主产区为河南、山东和河北,三省占据全国总产量的49%[6]。随着产量增加,在生产、运输和使用过程中难免会向环境中泄漏,在废品处置过程中(如垃圾焚烧、填埋等)也会源源不断地释放到环境中。不仅如此,CPs在焚烧过程中还会产生多种持久性氯化芳烃,如多氯联苯、多氯萘等,带来了一系列环境问题[7-8]。

海洋是各类持久性有机污染物(persistent organic pollutants, POPs)的汇,CPs作为POPs之一,加之其主要产区和消费区分布在东部沿海[6],使得我国海洋环境更易受到CPs的污染。有报道称,山东半岛渤海湾沿岸海水中SCCPs浓度为572.6~1 978 ng·L-1,平均值为1 256 ng·L-1[3];黄海沿岸海水中SCCPs浓度为370.0~543.3 ng·L-1,平均值为449.3 ng·L-1[3];珠江口海水中SCCPs浓度为180~460 ng·L-1[9];辽东湾海水中SCCPs浓度相对较低,为4.10~13.1 ng·L-1,平均7.70 ng·L-1[10]。此外,在渤海沿岸的陆地土壤(120.31 ng·g-1,干质量)、潮间带沉积物(203.17 ng·g-1,干质量)和海洋表层沉积物(259.64 ng·g-1,干质量)中均有SCCPs污染的报道[11]。CPs不仅存在于环境中,海洋生物体中也有检出。在渤海湾沿岸软体动物中,SCCPs浓度高达5 510 ng·g-1(干质量)[12];而在辽东湾鱼类体内SCCPs浓度在428~2 896 ng·g-1(湿质量),甲壳类为243~1 053 ng·g-1(湿质量),双壳贝类为1 058~2 259 ng·g-1(湿质量),此外,在珠江口鱼类和甲壳类体内也有报道,但含量相对较低[9]。SCCPs分布广泛,污染严重,且具有生物富集性、环境持久性等特征,因而被国内外学者广泛关注[13],2017年SCCPs也被列入斯德哥尔摩公约POPs清单[14]。

SCCPs作为新型污染物,关于其毒性的研究相对较少。现有研究表明,SCCPs具有致死性、致癌性和发育毒性,导致内分泌系统紊乱和代谢功能异常[15]。在哺乳动物小鼠(Mus musculus)的经口暴露实验中发现,SCCPs主要损伤肝脏、肾脏,并具有致死性、致癌性[16-17];对于内分泌系统的影响,主要是降低甲状腺素总T4浓度,引起促甲状腺素(TSH)和尿苷二磷酸葡醛酸转移酶(UDPGT)水平升高,导致甲状腺功能紊乱[7]。在非洲爪蟾(Xenopus laevis)的实验中发现SCCPs能够导致胚胎生长缓慢、发育畸形,并诱导了谷胱甘肽转移酶活性增加[18]。对于鱼类而言,SCCPs能够引起虹鳟幼鱼(Oncorhynchus mykiss)肝脏纤维损伤、肝细胞坏死和炎症反应[19];能够导致斑马鱼(Danio rerio)胚胎死亡率增加,孵化率降低,并影响甲状腺激素的代谢[20-21],在Ren等[22]在研究中发现SCCPs对斑马鱼胚胎13 d的LC50低至34.4 μg·L-1。关于SCCPs的毒性机制,一般认为可能是SCCPs与大分子结合,继而引起机体氧化应激、代谢紊乱、内分泌紊乱等有关[15]。现已证明,SCCPs会引起体外培养细胞产生氧化应激反应,导致活性氧(reactive oxygen species, ROS)积累,超氧化物歧化酶(superoxide dismutase, SOD)和过氧化氢酶(catalase, CAT)活性增加[23],而氧化应激会产生诸多不利影响,如破坏细胞成分,导致DNA损伤和基因突变等,因此,氧化应激可能是SCCPs毒性作用的基础[24-25],这也是本研究中重点关注鱼类胚胎氧化损伤的原因。

海洋是SCCPs污染的重灾区,但目前并没有关于SCCPs对海洋生物毒性效应的报道。褐牙鲆(Paralichthys olivaceus)是我国北方重要的经济鱼类和增殖放流的主要品种,其健康状况与人类息息相关,同时,褐牙鲆具有洄游习性,每年春季洄游至近岸产卵,受人类活动影响,近岸的底泥及海水中SCCPs污染更为严重[3],加之其胚胎、仔鱼的生理功能尚未发育完善,受SCCPs的影响可能更为严重。因此,本实验以褐牙鲆胚胎、仔鱼为研究对象,探究SCCPs对海洋鱼类的毒性效应。通过本研究,有助于进一步了解SCCPs的生态毒性,为制定和完善相关环境评价标准提供理论依据。

1 材料与方法(Materials and methods)

1.1 SCCPs溶液配制

实验中的SCCPs(CAS号85535-84-8,纯度≥99%)购自山东嘉颖化工科技有限公司。SCCPs用二甲基亚砜(DMSO,分析纯,中国国药有限公司)助溶后,按照实验分组配成相应的浓度,各组中DMSO浓度均为0.02%(V∶V),此外设置溶剂对照组,仅添加相同剂量的DMSO。

1.2 褐牙鲆胚胎的暴露实验

褐牙鲆胚胎购自烟台天源水产有限公司,待亲鱼产卵受精后,立即收集受精卵运回实验室进行随机分组。暴露实验在外径120 mm的培养皿中进行,按照实验浓度分成了0、0.1、1、10、100、1 000和10 000 μg·L-1组(0.1、1和10 μg·L-1组用于探究目前海水污染水平的毒性效应;100、1 000和10 000 μg·L-1组用于评估严重污染时的毒性效应)和溶剂对照组(0.02%的DMSO),每组3个平行,每个平行100粒胚胎,其中0、1、100和10 000 μg·L-1组和DMSO组额外多设置6个平行,用于测定胚胎抗氧化酶活性及相关抗氧化基因的表达情况。分组完成后待受精率发育至桑椹胚时(约受精后4 h,4 hpf),开始暴露实验。

整个暴露期间保持光周期14 L∶10 D、水温(18±1) ℃、盐度(33±1)‰、溶解氧(7.0±0.5) mg·L-1。

1.3 毒性终点统计和显微观察

实验中采用显微镜(LEICA-DM2500,德国)观察胚胎的发育情况,拍照记录畸形个体,判别畸形类型等,部分测量指标采用解剖镜(OLYMPUS-SZ61TR,日本)及其自带软件(Olympus cellSens)直接测量。统计的各毒性终点如表1所示。

表1 胚胎发育中各毒性终点及其说明

Table 1 Toxic endpoints and description in embryonic development

毒性终点Toxicity endpoints评价时间/hpfHours post-fertilization/hpf说明Description自主运动Spontaneous movement42胚胎尾部每分钟内自发地从一边摆动到另一边的次数;每组统计15枚Number of spontaneous tail movements per minute per embryo; 15 embryos were scored per group孵化率Hatching rate60、72累积孵化胚胎数/总卵数Cumulative hatched embryos/total number of embryos仔鱼体长Larval length132解剖镜下测量体长,每组统计15尾Measurement of body length under dissecting microscope, with 15 individuals per group畸形率Malformation rate132畸形仔鱼数/存活仔鱼总数Umber of malformed larvae/total number of surviving larvae死亡率Mortality rate132累计死亡数/总卵数Cumulative mortality/total number of embryos卵黄囊面积Yolk sac area132解剖镜下测量仔鱼卵黄囊面积,每组统计15尾Measurement of yolk sac area in larvae under dissecting microscope, with 15 individuals per group

1.4 抗氧化酶活性测定及相关抗氧化基因表达情况

实验结束后,0、1、100和10 000 μg·L-1组和DMSO组各取3个平行测定SOD(WST-1法)、CAT(钼酸铵法)的活性以及MDA(TBA法)的含量,所用试剂盒购自南京建成生物工程研究所,具体操作步骤按试剂盒说明书进行。

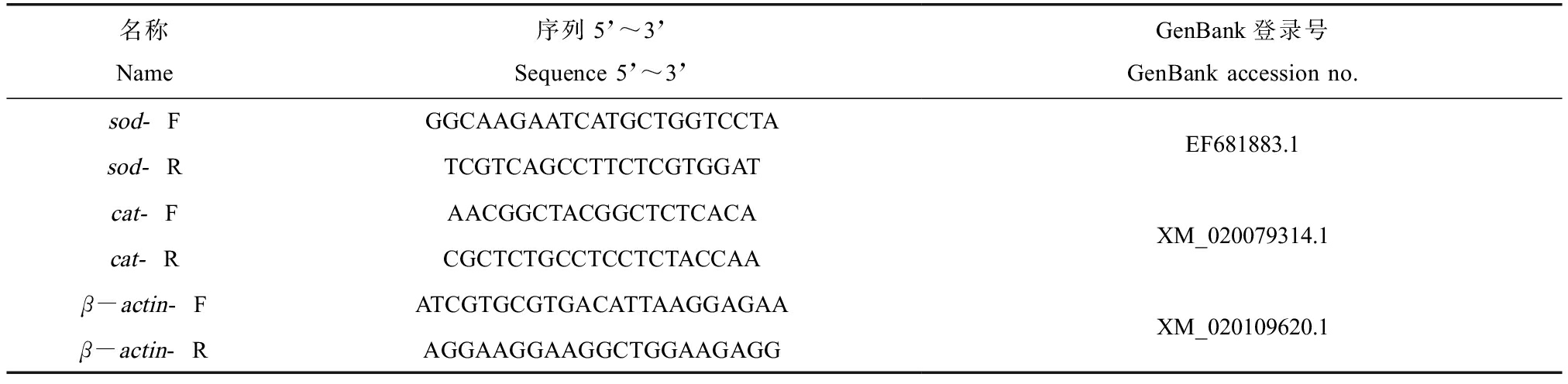

另外取0、1、100和10 000 μg·L-1组和DMSO组剩余的3个平行,以β-actin为内参基因,采用2-ΔΔCt法测定抗氧化基因sod和cat的表达水平。首先取0.1 g样品充分匀浆后使用Trizol试剂盒(生工生物工程股份有限公司)提取总RNA,使用超微分光光度计(NanoDropOne,Thermo,美国)测定总RNA的浓度和判断RNA的质量;随后使用MightyScript Plus第一链合成试剂盒(生工生物工程股份有限公司)合成cDNA;再用PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix试剂盒(赛默飞世尔科技公司)进行cDNA的扩增。反应体系为20 μL,反应程序和条件为:95 ℃下预变性2 min,95 ℃变性15 s,53 ℃退火15 s,72 ℃延伸1 min,重复40个循环。引物相关信息见表2。

表2 内参基因和目的基因引物信息

Table 2 Primer information of internal reference genes and target genes

名称Name序列5’~3’Sequence 5’~3’GenBank登录号GenBank accession no.sod-FGGCAAGAATCATGCTGGTCCTAsod-RTCGTCAGCCTTCTCGTGGATEF681883.1cat-FAACGGCTACGGCTCTCACAcat-RCGCTCTGCCTCCTCTACCAAXM_020079314.1β-actin-FATCGTGCGTGACATTAAGGAGAAβ-actin-RAGGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGAGGXM_020109620.1

1.5 数据统计与分析

利用SPSS 25软件对数据进行Kolmogorov-Smirnow正态分布检验和Levene方差齐性检验,满足2种检验条件后进行one-way ANOVA分析。利用Tukey test进行组间多重比较,在DMSO组与对照组无显著差异(P<0.05时表示差异显著)的基础上,以DMSO组为对照与各实验组进行比较。半致死浓度(LC50)通过Probit模型进行确定。数值结果以Mean±SD表示。

2 结果(Results)

2.1 SCCPs对褐牙鲆胚胎孵化的影响

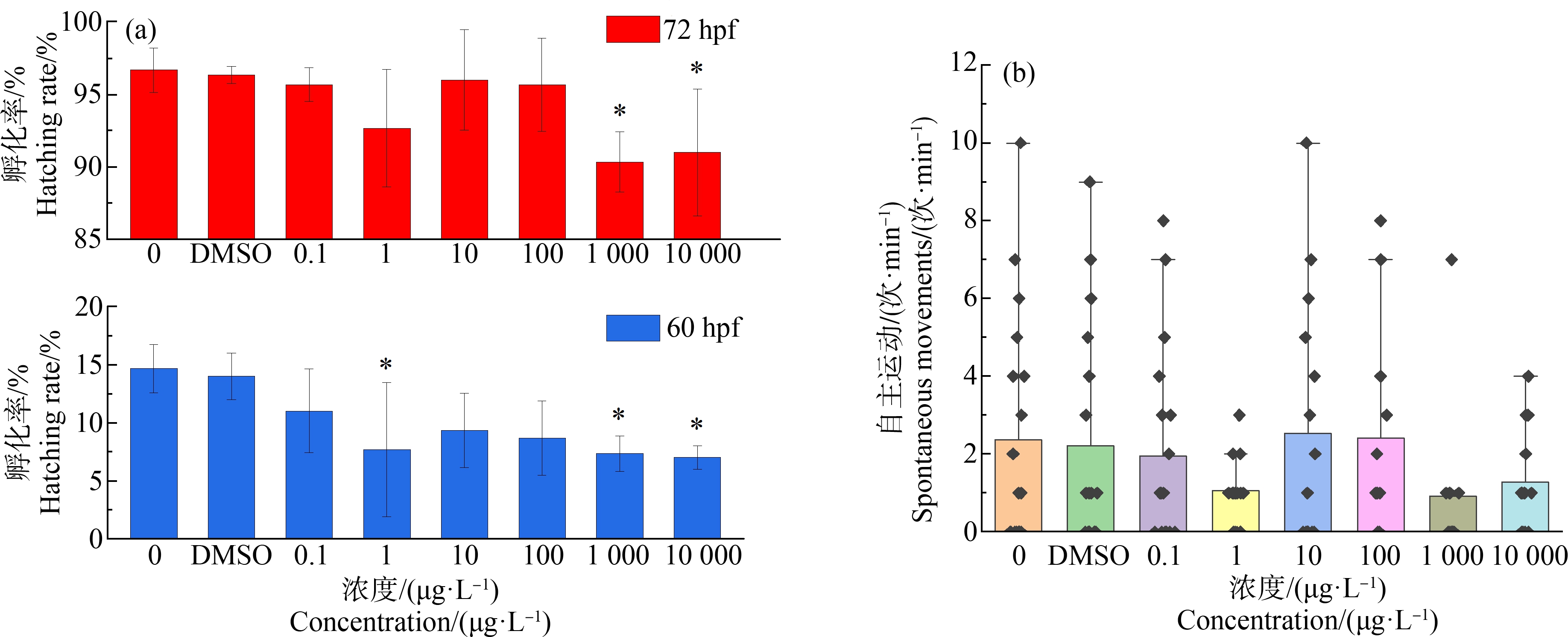

本研究统计了胚胎60 hpf、72 hpf的孵化率,结果如图1(a)所示。可见各实验组60 hpf的孵化率均小于对照组,表明SCCPs推迟了褐牙鲆胚胎的孵化,其中1、1 000和10 000 μg·L-1组的孵化率分别为(7.7±5.8)%、(7.3±1.5)%和(7.0±1.0)%,与对照组(14.7±2.1)%存在显著差异(P<0.05)。在受精后72 h时,对照组胚胎的孵化率达到了(96.3±0.5)%,而1 000 μg·L-1组和10 000 μg·L-1组分别为(90.3±2.1)%、(91.0±4.4)%,均与对照组存在显著差异(P<0.05),此时其他低浓度(0.1、1、10和100 μg·L-1)实验组的孵化率与对照组无显著差异(P>0.05),这表明高浓度的SCCPs胁迫会导致褐牙鲆胚胎孵化率下降,但低浓度胁迫时对胚胎孵化率没有影响。此外,在10 000 μg·L-1组还发现了部分出膜困难的胚胎(胚胎存活,但未孵化出膜),在受精后84 h和108 h时仍未出膜,如图2(e)、图2(i),可见这些胚胎表面粗糙,附有大量颗粒杂质。

图1 短链氯化石蜡(SCCPs)对褐牙鲆胚胎化率和自主运动的影响

注:(a)各组60 hpf和72 hpf的孵化率;(b) 各组胚胎42 hpf自主运动情况;*代表示实验组与对照组间P<0.05,**代表P<0.01,***P<0.001;下同

Fig. 1 The effect of short chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCPs) on embryo hatching rate and autonomous movement

Note: (a) Hatching rate of embryos at 60 hpf and 72 hpf; (b) Autonomous movement of embryos at 42 hpf; asterisks denote significant difference between treatments and control, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.01; the same below.

图2 SCCPs诱导褐牙鲆胚胎-仔鱼产生的畸形类型

注:(a)、(b)、(c)和(d)为对照组36 hpf、48 hpf、72 hpf和108 hpf的胚胎或仔鱼;(e)、(i)分别为实验组84 hpf、108 hpf未孵化出膜的胚胎(HF);(f)为实验组48 hpf卵黄囊水肿(YSE)的仔鱼;(g)、(h)分别为实验组96 hpf、108 hpf脊柱弯曲(SC)、鳍膜损伤(FD)的仔鱼;(j)为实验组60 hpf仔鱼(YSE、FD);(k)、(l)为实验组108 hpf心包水肿(PE)、SC和YSE的仔鱼。

Fig. 2 Types of malformations induced by SCCPs in the Paralichthys olivaceus embryos

Note: (a), (b), (c), (d) The control group embryos at 24, 48, 72 and 96 hpf, respectively; (e), (i) Hatch failure (HF) embryos in the treatments at 84 hpf, 108 hpf, respectively; (f) Embryo with yolk sac edema (YSE) at 48 hpf; (g), (h) Larvae with spinal curvature (SC), fin membrane damage (FD) in the treatments at 96 hpf, 108 hpf, respectively; (j) Larvae with YSE and FD in the treatments at 60 hpf; (k), (l) Larvae with pericardial edema (PE), SC and YSE in the treatments at 108 hpf.

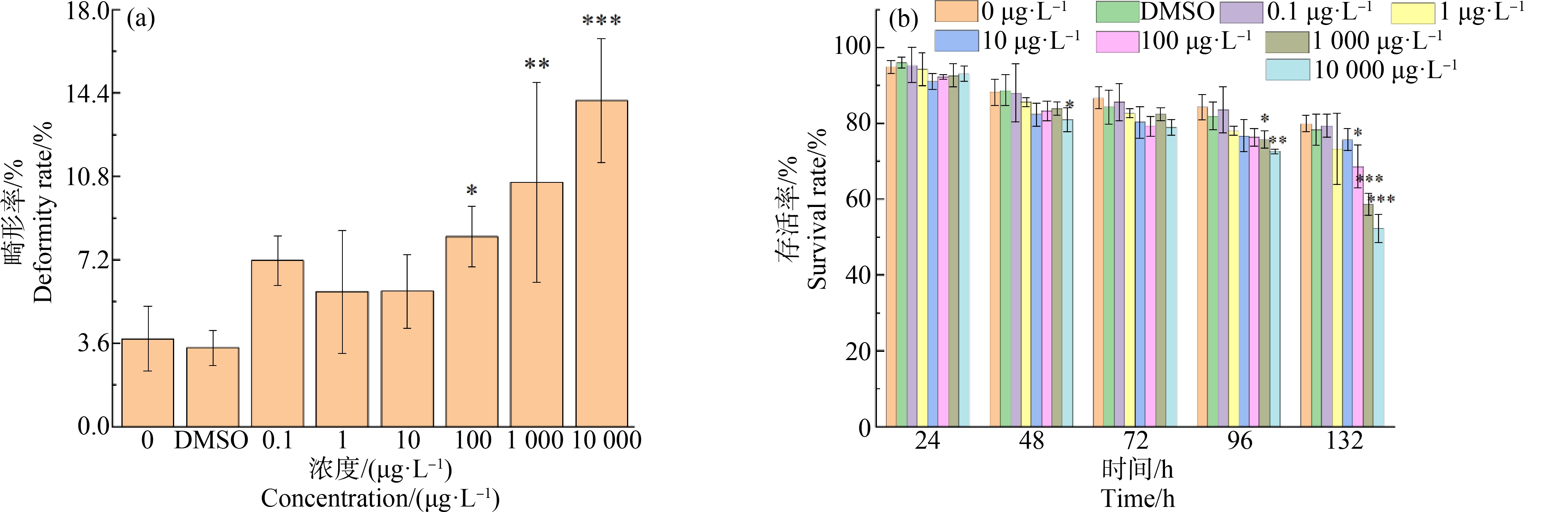

2.2 SCCPs对褐牙鲆胚胎致畸、致死作用

研究发现SCCPs对褐牙鲆胚胎具有致畸作用,且存在明显的剂量效应。如图3(a)所示,120 hpf时100、1 000和10 000 μg·L-1组的畸形率分别为(8.2±1.3)%、(10.6±4.3)%和(14.1±2.7)%,与对照组(3.8±1.4)%均有显著差异(P<0.05),但0.1、1和10 μg·L-1各组与对照组相比差异不显著(P>0.05)。在畸形个体中,畸形类型主要为脊柱弯曲(图2(g)、图2(h)、图2(k)、图2(l))、卵黄囊水肿(图2(f)、图2(j)、图2(l))、心包水肿(图2(k)、图2(l))、鳍膜损伤(图2(g)、图2(h)、图2(j)),同时发现随着暴露时间延长,畸形个体一般会同时表现出多种畸形类型,其中水肿现象较为普遍。

图3 SCCPs对褐牙鲆胚胎-仔鱼畸形率和存活率的影响

Fig. 3 Effect of SCCPs on embryonic malformation and survival rate of Paralichthys olivaceus

各组存活率的统计结果如图3(b)所示,在实验结束时(132 hpf),对照组存活率为(78.3±2.1)%,而100、1 000和10 000 μg·L-1组的分别为(68.7±2.9)%、(58.7±5.7)%和(52.3±2.8)%,与对照组均有显著差异(P<0.05),其他各浓度实验组则与对照无显著差异(P>0.05)。可见随着暴露浓度增加,存活率逐渐下降,表现出剂量效应。随着暴露时间增长,各实验组存活率逐渐降低,尤其是96~132 h高浓度实验组(100、1 000和10 000 μg·L-1组)仔鱼的存活率急速下降,时间效应明显。此外,通过Probit模型估算的SCCPs对褐牙鲆胚胎132 h-LC50为49 743.34 μg·L-1。

2.3 SCCPs对胚胎-仔鱼生长和卵黄吸收的影响

实验中SCCPs对褐牙鲆仔鱼表现出了生长抑制作用,如图4(a)所示,实验结束时(132 hpf)对照组仔鱼体长为(34.0±2.9) mm,高于各浓度的实验组,并与1、10、100、1 000和10 000 μg·L-1组差异显著(P<0.05)。如图4(b)所示,实验结束时(132 hpf)对照组卵黄囊面积要大于各实验组,且与各实验组均有显著差异(P<0.05)。

图4 SCCPs对褐牙鲆胚胎-仔鱼体长和卵黄囊面积的影响

Fig. 4 Effect of SCCPs on larvae body length and yolk sac area in Paralichthys olivaceus

2.4 SCCPs对仔鱼抗氧化系统的影响

SCCPs对褐牙鲆抗氧化酶SOD、CAT的活性及脂质过氧化产物MDA含量的影响如图5和图6所示。与对照组相比,SCCPs诱导了褐牙鲆仔鱼SOD活性增加,其中1 μg·L-1组的SOD活性为(95.53±3.32) U·mg-1,较对照组显著增加了192.3%(P<0.05);100 μg·L-1组的SOD活性为(54.10±8.52) U·mg-1,较对照组显著增加了65.53%(P<0.05);10 000 μg·L-1组的SOD活性为(40.12±3.06) U·mg-1,较对照组显著增加了22.8%(P<0.05)。同样,实验组CAT活性也高于对照组(0.42±0.09) U·mg-1,1、100和10 000 μg·L-1组分别为(1.27±0.30) U·mg-1、(0.78±0.09) U·mg-1和(0.73±0.19) U·mg-1。仔鱼sod、cat基因表达情况如图5(b)、5(d)所示,各实验组两基因的表达量均高于对照组,且随着实验浓度增加,基因表达情况有所抑制,这一规律也与抗氧化酶活力的变化相对应。

图5 SCCPs诱导褐牙鲆仔鱼产生的氧化应激

Fig. 5 SCCPs induced oxidative stress in Paralichthys olivaceus

图6 SCCPs诱导褐牙鲆仔鱼产生的丙二醛(MDA)

Fig. 6 SCCPs induced malonaldehyde (MDA) in Paralichthys olivaceus

对于MDA而言,本研究中1 μg·L-1组MDA含量为(13.32±0.24) nmol·mg-1,100 μg·L-1为(12.95±1.79) nmol·mg-1,10 000 μg·L-1组为(25.61±0.12) nmol·mg-1,均显著高于对照组的(8.86±1.44) nmol·mg-1(P<0.05),特别是10 000 μg·L-1组,MDA含量接近于对照组的3倍,表明机体已发生了严重的氧化应激反应。

3 讨论(Discussion)

SCCPs暴露会引起胚胎孵化延迟,高浓度胁迫时还会导致孵化率降低,如图1(a)所示。这一现象在斑马鱼中也有报道[21-22],但对其他水生生物孵化的影响还需要进一步研究。孵化是鱼类早期发育阶段的重要一环,一般包括2个过程,一是孵化腺分泌孵化酶、绒毛膜酶,引起卵膜膨胀、降解[26-27],二是胚胎机械运动使卵膜破裂[28-29]。本研究中发现SCCPs能够影响褐牙鲆胚胎的孵化,这与以上过程可能有关,遗憾的是本研究并没有对孵化酶进行研究。但关于胚胎的机械运动,我们发现在42 h时1、1 000和10 000 μg·L-1组胚胎的自主运动次数要低于对照组(图1(b)),均在4 次·min-1以下,由于这些胚胎自主运动的强度减弱,很难突破卵膜,使得实验组60 hpf的孵化率低于对照组,表现出孵化延迟的现象。而对于高浓度组出现胚胎出膜困难的现象,一方面可能是SCCPs抑制了胚胎的自主运动,使得胚胎出膜困难;另一方面可能是由于SCCPs具有亲脂性,大量附着在卵膜表面,呈现出颗粒状态(图2(e)、图2(i)),阻塞了气孔造成胚胎缺氧[30];早期研究,缺氧能够抑制胚胎发育,导致孵化延迟或死亡[31]。

SCCPs对褐牙鲆胚胎-仔鱼具有明显致死作用,这在非洲爪蟾[18]、虹鳟鱼[19]和斑马鱼[20]中均有报道。本实验中观察到SCCPs对褐牙鲆胚胎132 h的LC50为49 743.34 μg·L-1,而刘丽华等[21]发现SCCPs对斑马鱼胚胎96 h的LC50为1~10 mg·L-1,Fisk等[32]在日本青鳉鱼(Oryzias latipes)胚胎中发现其LC50值2.7~9.6 mg·L-1,相比较均低于本实验观察到的结果,这可能是物种耐受性不同引起的。值得注意的是Ren等[22]同样采用斑马鱼作为受试动物,在13 d的慢性毒性实验中发现SCCPs的LC50低至34.4 μg·L-1,可见暴露时间越长,其水生生物毒性越大,特别是对水生生物长期暴露的影响还需进一步深入研究。

诸多研究表明,环境污染物能够导致鱼类胚胎发育畸形[20,22,33-34]。本研究发现SCCPs对褐牙鲆胚胎同样具有致畸作用,且存在明显的剂量效应。Liu等[20]研究发现,SCCPs对斑马鱼胚胎发育毒性也具有低浓度致畸作用不明显、高浓度致畸作用显著的规律。值得注意的是,在畸形类型中水肿发生率较高,污染物导致鱼类水肿的发生可能与膜的通透性有关[35]。MDA作为脂质过氧化物,其含量能够反映生物膜受损程度,研究中观察到实验组仔鱼MDA含量显著高于对照组(图6),表明仔鱼体内生物膜发生了严重的脂质过氧化作用,生物膜结构和功能的损伤势必会影响其功能,改变通透性[36],最终导致了实验组大量水肿个体产生。此外,在实验结束时存活仔鱼中畸形个体仍占有一定量比例,对于畸形胚胎而言大多数最终会走向死亡[23],存活率会进一步降低。

体长是衡量仔鱼生长发育状况最直观的指标。由于整个实验过程处于内源性营养阶段,卵黄提供了胚胎生长发育所需的所有能量,卵黄囊面积在一定程度上能够反映胚胎-仔鱼能量利用的情况。我们结合体长规律发现,实验组胚胎-仔鱼消耗的能量多反而生长较慢(图4),这一现象在斑马鱼胚胎中也有发现[20],这可能是由于胚胎-仔鱼面临SCCPs的毒性胁迫,消耗了大量的能量用于解毒[37],导致分配给生长的能量减少,因而生长缓慢。

正常情况下,机体内ROS处于动态平衡状态,当受到污染物胁迫致使ROS积累时,机体的抗氧化系统会发挥作用,维持ROS代谢平衡,避免细胞遭受氧化损伤,影响组织、器官的功能。SOD和CAT是机体抗氧化防御系统的第一道防线[38],ROS过量时会诱导其活性增加,SOD能够催化![]() 生成毒性较低的H2O2,而CAT负责催化H2O2分解成H2O和O2[39],因此,SOD和CAT的活性能够间接反映机体的氧化损伤情况,也被广泛地用于评价污染物的毒性效应中[40-42]。本研究中褐牙鲆仔鱼SOD、CAT活性及sod、cat基因的表达情况均显著高于对照组,表明SCCPs诱导机体发生了氧化应激反应,进而导致细胞损伤、凋亡,最终影响着生物体的代谢和免疫调节等[43]。研究发现,青鳉鱼幼鱼[44]、热带爪蛙胚胎[45]随着SCCPs暴露浓度的增加,机体SOD、CAT都呈下降趋势。原因可能是低浓度处理时,仔鱼产生适应性反应,通过提升抗氧化酶活性来消除ROS,保护机体免受氧化损伤;但随着SCCPs暴露浓度增加,机体产生的ROS大量积累,超过了抗氧化防御系统清除能力,过量ROS损伤抗氧化系统,致使抗氧化酶活性下降、相关抗氧化酶基因下调[46]。此外,由于MDA依赖于SOD进行清除,随着SCCPs浓度增加,SOD的活性逐渐下降,使得体内MDA含量增加,实验中SOD和MDA的变化规律也对应了起来。综上所述,我们认为SCCPs引起的氧化应激可能是导致褐牙鲆胚胎-仔鱼发育异常(畸形、死亡等)的主要原因,而这种氧化损伤即使在环境浓度(1 μg·L-1)下也会存在,结合其他毒性终点观察到的结果,我们认为短期环境浓度的SCCPs胁迫虽未导致鱼类存活率显著下降,但对鱼类的正常发育已产生影响。长期来看,这种影响可能会打破近海生态系统的稳定,导致鱼类资源量进一步下降。

生成毒性较低的H2O2,而CAT负责催化H2O2分解成H2O和O2[39],因此,SOD和CAT的活性能够间接反映机体的氧化损伤情况,也被广泛地用于评价污染物的毒性效应中[40-42]。本研究中褐牙鲆仔鱼SOD、CAT活性及sod、cat基因的表达情况均显著高于对照组,表明SCCPs诱导机体发生了氧化应激反应,进而导致细胞损伤、凋亡,最终影响着生物体的代谢和免疫调节等[43]。研究发现,青鳉鱼幼鱼[44]、热带爪蛙胚胎[45]随着SCCPs暴露浓度的增加,机体SOD、CAT都呈下降趋势。原因可能是低浓度处理时,仔鱼产生适应性反应,通过提升抗氧化酶活性来消除ROS,保护机体免受氧化损伤;但随着SCCPs暴露浓度增加,机体产生的ROS大量积累,超过了抗氧化防御系统清除能力,过量ROS损伤抗氧化系统,致使抗氧化酶活性下降、相关抗氧化酶基因下调[46]。此外,由于MDA依赖于SOD进行清除,随着SCCPs浓度增加,SOD的活性逐渐下降,使得体内MDA含量增加,实验中SOD和MDA的变化规律也对应了起来。综上所述,我们认为SCCPs引起的氧化应激可能是导致褐牙鲆胚胎-仔鱼发育异常(畸形、死亡等)的主要原因,而这种氧化损伤即使在环境浓度(1 μg·L-1)下也会存在,结合其他毒性终点观察到的结果,我们认为短期环境浓度的SCCPs胁迫虽未导致鱼类存活率显著下降,但对鱼类的正常发育已产生影响。长期来看,这种影响可能会打破近海生态系统的稳定,导致鱼类资源量进一步下降。

[1] Environment Canada and Health Canada. Priority substances list assessment report [R]. Ottawa, Ontario: Environment Canada and Health Canada, 1993: 56

[2] Reth M, Oehme M. Limitations of low resolution mass spectrometry in the electron capture negative ionization mode for the analysis of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins [J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2004, 378(7): 1741-1747

[3] Zhao N, Cui Y, Wang P W, et al. Short-chain chlorinated paraffins in soil, sediment, and seawater in the intertidal zone of Shandong Peninsula, China: Distribution and composition [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 220: 452-458

[4] Bayen S, Obbard J P, Thomas G O. Chlorinated paraffins: A review of analysis and environmental occurrence [J]. Environment International, 2006, 32(7): 915-929

[5] Feo M L, Eljarrat E, Barceló D, et al. Occurrence, fate and analysis of polychlorinated n-alkanes in the environment [J]. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2009, 28(6): 778-791

[6] 郑结斌. 中国氯化石蜡行业现状及发展分析 [J]. 中国氯碱, 2021(1): 22-24

[7] Fiedler H. Short-chain Chlorinated Paraffins: Production, Use and International Regulations [M]// Boer J. Chlorinated Paraffins. Springer Link, 2010: 1-40

[8] Yuan S C, Wang M, Lv B, et al. Transformation pathways of chlorinated paraffins relevant for remediation: A mini-review [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2021, 28(8): 9020-9028

[9] Huang Y M, Chen L G, Jiang G, et al. Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of short-chain chlorinated paraffins in marine organisms from the Pearl River Estuary, South China [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 671: 262-269

[10] Ma X D, Zhang H J, Wang Z, et al. Bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of short chain chlorinated paraffins in a marine food web from Liaodong Bay, North China [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2014, 48(10): 5964-5971

[11] 崔阳. 山东半岛沿岸短链氯化石蜡的分布、组成、迁移规律及其影响因素[D]. 济南: 山东大学, 2018: 28-35

[12] Yuan B, Wang T, Zhu N L, et al. Short chain chlorinated paraffins in mollusks from coastal waters in the Chinese Bohai Sea [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2012, 46(12): 6489-6496

[13] Zeng L X, Zhao Z S, Li H J, et al. Distribution of short chain chlorinated paraffins in marine sediments of the East China Sea: Influencing factors, transport and implications [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2012, 46(18): 9898-9906

[14] Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee. Recommendation by the Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee to list short-chain chlorinated paraffins in annex A to the convention [C]. Stockholm: United Nations Environment Programme, 2017: 35-36

[15] Wang X, Zhu J B, Xue Z M, et al. The environmental distribution and toxicity of short-chain chlorinated paraffins and underlying mechanisms: Implications for further toxicological investigation [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 695: 133834

[16] Ali T E S, Legler J. Overview of the Mammalian and Environmental Toxicity of Chlorinated Paraffins [M]// Boer J. Chlorinated Paraffins. Springer Link, 2010: 135-154

[17] Bucher J R, Alison R H, Montgomery C A, et al. Comparative toxicity and carcinogenicity of two chlorinated paraffins in F344/N rats and B6C3F1 mice [J]. Toxicological Sciences, 1987, 9(3): 454-468

[18] ![]() á B, Blaha L, Vršková D, et al. Sublethal toxic effects and induction of gGutathione S-transferase by short-chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCPs) and C-12 alkane (dodecane) in Xenopus laevis frog embryos [J]. Acta Veterinaria Brno, 2006, 75(1): 115-122

á B, Blaha L, Vršková D, et al. Sublethal toxic effects and induction of gGutathione S-transferase by short-chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCPs) and C-12 alkane (dodecane) in Xenopus laevis frog embryos [J]. Acta Veterinaria Brno, 2006, 75(1): 115-122

[19] Cooley H M, Fisk A T, Wiens S C, et al. Examination of the behavior and liver and thyroid histology of juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) exposed to high dietary concentrations of C(10)-, C(11)-, C(12)- and C(14)-polychlorinated n-alkanes [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2001, 54(1-2): 81-99

[20] Liu L H, Li Y F, Coelhan M, et al. Relative developmental toxicity of short-chain chlorinated paraffins in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 219: 1122-1130

[21] 刘丽华, 马万里, 刘丽艳, 等. 短链氯化石蜡C10(50.2% Cl)对斑马鱼胚胎的发育毒性[J]. 哈尔滨工业大学学报, 2016, 48(8): 127-130, 140

Liu L H, Ma W L, Liu L Y, et al. Study on developmental toxicity of short-chain chlorinated paraffins C10(50.2% Cl) in zebrafish embryos [J]. Journal of Harbin Institute of Technology, 2016, 48(8): 127-130, 140 (in Chinese)

[22] Ren X Q, Zhang H J, Geng N B, et al. Developmental and metabolic responses of zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos and larvae to short-chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCPs) exposure [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 622-623: 214-221

[23] Geng N B, Zhang H J, Zhang B Q, et al. Effects of short-chain chlorinated paraffins exposure on the viability and metabolism of human hepatoma HepG2 cells [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2015, 49(5): 3076-3083

[24] 王菲迪, 张海军, 耿柠波, 等. 短链氯化石蜡(SCCPs)和多环芳烃(PAHs)联合暴露对HepG2细胞抗氧化系统的影响[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2018, 13(5): 218-225

Wang F D, Zhang H J, Geng N B, et al. Combined effects of SCCPs and PAHs on the antioxidant system in HepG2 cells [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2018, 13(5): 218-225 (in Chinese)

[25] Chen J W, Ni B B, Li B, et al. The responses of autophagy and apoptosis to oxidative stress in nucleus pulposus cells: Implications for disc degeneration [J]. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry: International Journal of Experimental Cellular Physiology, Biochemistry, and Pharmacology, 2014, 34(4): 1175-1189

[26] Lepage T, Sardet C, Gache C. Spatial expression of the hatching enzyme gene in the sea urchin embryo [J]. Developmental Biology, 1992, 150(1): 23-32

[27] Araki K, Fujikawa N, Nakayama I, et al. Early expression of a hatching enzyme gene in Masu salmon (Oncorhynchus masou) embryos [J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2011, 53(3): 509-512

[28] 赵君. 中国对虾(Penaeus chinensis)孵化酶的分离纯化、性质及其鉴定研究[D]. 青岛: 中国海洋大学, 2007: 14-18

[29] Sano K, Inohaya K, Kawaguchi M, et al. Purification and characterization of zebrafish hatching enzyme—An evolutionary aspect of the mechanism of egg envelope digestion [J]. The FEBS Journal, 2008, 275(23): 5934-5946

[30] Samaee S M, Rabbani S, ![]() B, et al. Efficacy of the hatching event in assessing the embryo toxicity of the nano-sized TiO2 particles in zebrafish: A comparison between two different classes of hatching-derived variables [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2015, 116: 121-128

B, et al. Efficacy of the hatching event in assessing the embryo toxicity of the nano-sized TiO2 particles in zebrafish: A comparison between two different classes of hatching-derived variables [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2015, 116: 121-128

[31] Hendon L A. Cross-talk between pyrene and hypoxia signaling pathways in embryonic Cyprinodon variegatus [D]. Hattiesburg: University of Southern Mississippi, 2006: 19-25

[32] Fisk A, Tomy G, Muir D. Toxicity of C 10-, C 11-, C 12-, and C 14- polychlorinated alkanes to Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) embryos [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 1999, 18(12): 2894-2902

[33] Vieira R, Ven ncio C A S, Félix L M. Toxic effects of a mancozeb-containing commercial formulation at environmental relevant concentrations on zebrafish embryonic development [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2020, 27(17): 21174-21187

ncio C A S, Félix L M. Toxic effects of a mancozeb-containing commercial formulation at environmental relevant concentrations on zebrafish embryonic development [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2020, 27(17): 21174-21187

[34] Sultana Z, Khan M M, Mostakim G M, et al. Studying the effects of profenofos, an endocrine disruptor, on organogenesis of zebrafish [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2021, 28(16): 20659-20667

[35] Hill A J, Bello S M, Prasch A L, et al. Water permeability and TCDD-induced edema in zebrafish early-life stages [J]. Toxicological Sciences: An Official Journal of the Society of Toxicology, 2004, 78(1): 78-87

[36] Carbajal-Hernández A L, Valerio-García R C, Martínez-Ruíz E B, et al. Maternal-embryonic metabolic and antioxidant response of Chapalichthys pardalis (Teleostei: Goodeidae) induced by exposure to 3,4-dichloroaniline [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2017, 24(21): 17534-17546

[37] Berntssen M H G, Aatland A, Handy R D. Chronic dietary mercury exposure causes oxidative stress, brain lesions, and altered behaviour in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) parr [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2003, 65(1): 55-72

[38] Verlecar X N, Jena K B, Chainy G B N. Modulation of antioxidant defences in digestive gland of Perna viridis (L.), on mercury exposures [J]. Chemosphere, 2008, 71(10): 1977-1985

[39] 周启星. 生态毒理学[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2004: 28-30

[40] Atli G, Alptekin O, Tükel S, et al. Response of catalase activity to Ag+, Cd2+, Cr6+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ in five tissues of freshwater fish Oreochromis niloticus [J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Toxicology &Pharmacology, 2006, 143(2): 218-224

[41] Larose C, Canuel R, Lucotte M, et al. Toxicological effects of methylmercury on walleye (Sander vitreus) and perch (Perca flavescens) from lakes of the boreal forest [J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Toxicology &Pharmacology, 2008, 147(2): 139-149

[42] Guilherme S, Válega M, Pereira M E, et al. Antioxidant and biotransformation responses in Liza aurata under environmental mercury exposure—Relationship with mercury accumulation and implications for public health [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2008, 56(5): 845-859

[43] Liang X M, Wang F, Li K B, et al. Effects of norfloxacin nicotinate on the early life stage of zebrafish (Danio rerio): Developmental toxicity, oxidative stress and immunotoxicity [J]. Fish &Shellfish Immunology, 2020, 96: 262-269

[44] Yang W K, Chiang L F, Tan S W, et al. Environmentally relevant concentrations of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate exposure alter larval growth and locomotion in medaka fish via multiple pathways [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 640-641: 512-522

[45] 李磊, 蒋玫, 王云龙. 邻苯二甲酸二丁酯和邻苯二甲酸二辛酯对大黄鱼受精卵及仔鱼的急性毒性效应[J]. 海洋渔业, 2019, 41(3): 346-353

Li L, Jiang M, Wang Y L. Toxic effects of DBP and DOP on early life stage of Pseudosciaena crocea [J]. Marine Fisheries, 2019, 41(3): 346-353 (in Chinese)

[46] 王艳, 马泽民, 吴石金. 3种PAEs对蚯蚓的毒性作用和组织酶活性影响的研究[J]. 环境科学, 2014, 35(2): 770-779

Wang Y, Ma Z M, Wu S J. Study on the effect of enzymatic activity and acute toxicity of three PAEs on Eisenia foetida [J]. Environmental Science, 2014, 35(2): 770-779 (in Chinese)