随着2005年溴代阻燃剂在全球范围内被逐步禁用,作为溴代阻燃剂的替代物,有机磷酸酯阻燃剂(organophosphorus flame retardants, OPFRs)被广泛应用于塑料制品、装修材料、电子产品和建筑材料中,以降低各种产品的易燃性。据估计,全球OPFRs的年均消费增长率为4.9%[1]。环境调查数据显示,OPFRs已成为环境介质中检出频率较高和存在范围较广的一类化学污染物[2]。

磷酸三苯酯(triphenyl phosphate, TPhP)是一种最常见的芳香基OPFRs,由于具有良好的阻燃性和增塑性,被广泛用于聚氯乙烯、电子产品及液压油中[3]。与其他OPFRs类似,TPhP主要以物理添加方式而非化学键合的方式存在,因此很容易从各种产品中释放进入环境。多项研究表明,TPhP广泛存在于包括空气、水、土壤、灰尘和沉积物等在内的多种环境介质中,甚至在人体样本如血液、胎盘、尿液和母乳中也有较高检出,具有分布广、检出率高、浓度高等特点[1-5]。例如,在我国的室内灰尘中,TPhP的平均浓度为610 ng·g-1[6]。Li等[7]发现,在广东廉江电子垃圾回收区的沉积物中,TPhP的浓度高达4 260~1 710 000 ng·g-1。在中国华北地区,95%的河流水样中检出TPhP,最高浓度为15.7 ng·L-1[8]。此外,在人体样本中也检测到了TPhP,He等[9]研究发现,儿童尿液中的TPhP浓度为0.3 ng·L-1。我国渤海湾人体血清中,TPhP的平均浓度为10.2 ng·g-1[10]。北京地区采集的母乳中,TPhP是检出频率最高的有机磷酸酯阻燃剂之一,检出率高达99%,中间浓度值为1 070 ng·L-1[11]。

TPhP引起的健康危害日益加剧,对生态稳定和人类健康的毒理效应逐步显露[4-5]。毒理学数据表明,TPhP具有神经毒性、生殖发育毒性、肝脏毒性及内分泌干扰作用等多种毒性效应[2],但目前对肺脏的毒性研究明显不足,仅有的文献显示,TPhP可导致肺细胞内活性氧(reactive oxygen species, ROS)水平升高和DNA损伤加剧[12]。肺脏是人体的呼吸器官,是机体进行气体交换的重要场所,TPhP具有较高的挥发性,极易通过呼吸系统直接进入人体的肺部组织,从而对人体的肺细胞造成极大的危害,因此,有必要研究TPhP对肺细胞的毒理效应。

本研究拟选择人源的非小细胞肺癌细胞系(human lung carcinoma cell line, A549)为研究对象,采用高内涵细胞表型分析技术平台,系统地测定TPhP的肺细胞毒性表型特征,明确TPhP的肺细胞毒性效应,为科学评估TPhP的人体健康风险提供理论依据和数据支持。

1 材料与方法(Materials and methods)

1.1 药物和试剂

Ham’s F-12K培养基购自武汉普诺赛生命科技有限公司;胎牛血清(fetal bovine serum, FBS)、胰蛋白酶、抗生素、细胞核染料Hoechst 33342、细胞核膜通透性染料TOTO-3、活性氧染料CM-H2DCFDA、线粒体膜电位染料JC-1、线粒体探针Mito Tracker Green、细胞凋亡检测染料、小鼠抗细胞色素C单克隆抗体(33-8200)、兔抗磷酸化组蛋白(phosphorylated histones H2AX, pH2AX)单克隆抗体(MA5-33062)、Alexa Fluor Plus 488标记的羊抗小鼠IgG二抗(A32723)、Alexa Fluor Plus 555标记的羊抗兔IgG二抗(A32732)均购自美国Thermo Fisher公司;TPhP(纯度≥99%,CAS 115-86-6),二甲基亚砜(dimethyl sulphoxide, DMSO)购自美国Sigma公司;细胞计数试剂盒(cell counting kit-8, CCK-8)和牛血清白蛋白(bovine serum albumin, BSA)购自碧云天生物科技有限公司;96孔细胞培养板、96孔底透黑板、6孔细胞培养板、15 mL无菌离心管等细胞培养器皿均购自美国Corning公司。多聚甲醛溶液、TritonX-100、酒精及其他常规化学试剂为国产试剂。

1.2 细胞培养与处理

A549细胞购自上海复祥生物科技有限公司,细胞接种于含10% FBS的F-12K培养液,37 ℃、5%CO2培养箱中培养。A549细胞以每孔1×104接种于96孔细胞培养板(黑边底透)中,培养箱中培养过夜。TPhP溶解于DMSO制成不同浓度的暴露溶液,等量的DMSO作为溶剂对照组。

1.3 细胞活性检测

A549细胞经0~200 μmol·L-1 TPhP染毒24 h后,采用CCK-8试剂进行细胞活性的检测。每孔加入10 μL CCK-8试剂,在细胞培养箱中继续孵育2~3 h。实验结束后,用多功能酶标仪测定450 nm处的吸光值(optical density, OD)。细胞存活率计算公式如下:

细胞存活率/% = [OD(450)实验组-OD(450)调零]/[OD(450)对照组-OD(450)调零]×100%。

1.4 细胞核和核膜通透性(nuclear membrane permeability, NMP)分析

用预热至37 ℃的磷酸盐缓冲生理盐水(phosphate buffered saline, PBS)配制含有细胞核染料Hoechst 33342和核膜通透性染料TOTO-3的混合细胞染料。A549细胞进行50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP染毒24 h后(后续实验的染毒剂量与此相同),用PBS洗2次,每孔加入100 μL染色工作液,于37 ℃避光染色15 min,洗板后,再次加入PBS上机检测。

1.5 细胞活性氧(ROS)和线粒体膜电位(mitochondrial membrane potential, MMP)检测

用预热至37 ℃的PBS配制含有细胞核染料Hoechst 33342和活性氧染料CM-H2DCFDA的混合细胞染料进行ROS的检测;用含有细胞核染料Hoechst 33342和线粒体膜电位染料JC-1的混合细胞染料进行MMP的测定。染毒处理24 h后,用PBS洗涤细胞,每孔加入100 μL染色工作液,于37 ℃避光染色15 min或20 min。洗板后,再次加入PBS上机检测。MMP以红色/绿色荧光的比值来衡量线粒体去极化的程度,比值越高表明线粒体去极化越低,MMP增加,反之去极化增加,MMP下降。

1.6 线粒体纹理结构分析

给药处理24 h后,吸弃96孔板中的培养基,每孔细胞用PBS轻轻洗涤2次,用预热至37 ℃的HBSS配制线粒体荧光探针染料Mito Tracker Green,于37 ℃避光染色1 h。洗板后,用细胞核染料Hoechst 33342染色10~15 min。洗板后,再次加入PBS上机检测。

1.7 pH2AX蛋白和细胞色素C蛋白的检测

给药处理24 h后,吸弃96孔板中的培养基,每孔细胞用PBS轻轻洗涤1次,先用4%多聚甲醛溶液固定15 min,再用0.1% Triton X-100透膜10 min,吸弃透膜液,PBS洗板后,加入含3% BSA的封闭液,室温孵育30 min,吸弃封闭液,加入一抗工作液(小鼠抗细胞色素C抗体按1∶300稀释,兔抗pH2AX抗体按1∶200稀释),4 ℃避光孵育过夜。吸弃一抗工作液,用PBS清洗细胞3次,再加入对应的二抗工作液(Alexa Fluor Plus 488标记的羊抗小鼠IgG二抗按1∶1 000稀释,或Alexa Fluor Plus 555标记的羊兔IgG二抗按1∶500稀释),37 ℃避光孵育1 h。吸弃二抗工作液,用PBS清洗细胞2次,用细胞核染料Hoechst 33342染色10~15 min,洗板后采用高内涵分析仪进行检测。

1.8 细胞凋亡检测

用Annexin V结合缓冲液配制染色工作液,染色工作液为Annexin V、PI和Hoechst 33342的混合细胞染料。给药处理24 h后,吸弃96孔板中的培养基,用预冷的PBS轻轻洗涤细胞2次,每孔加入50 μL染色工作液,于37 ℃避光染色15 min,洗板后,再次加入PBS上机检测。

1.9 统计学处理

采用SPSS 21.0统计分析软件进行单因素方差分析(ANOVA),数据结果用平均值±标准误差表示,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。细胞凋亡率由高内涵分析系统的Harmony 4.9图像分析软件直接得出。TPhP抑制50%细胞活性时的浓度值(half maximal inhibitory concentration, IC50)由GraphPad Prism 8.0软件进行非线性回归分析得出。

2 结果(Results)

2.1 TPhP对A549细胞活性的影响

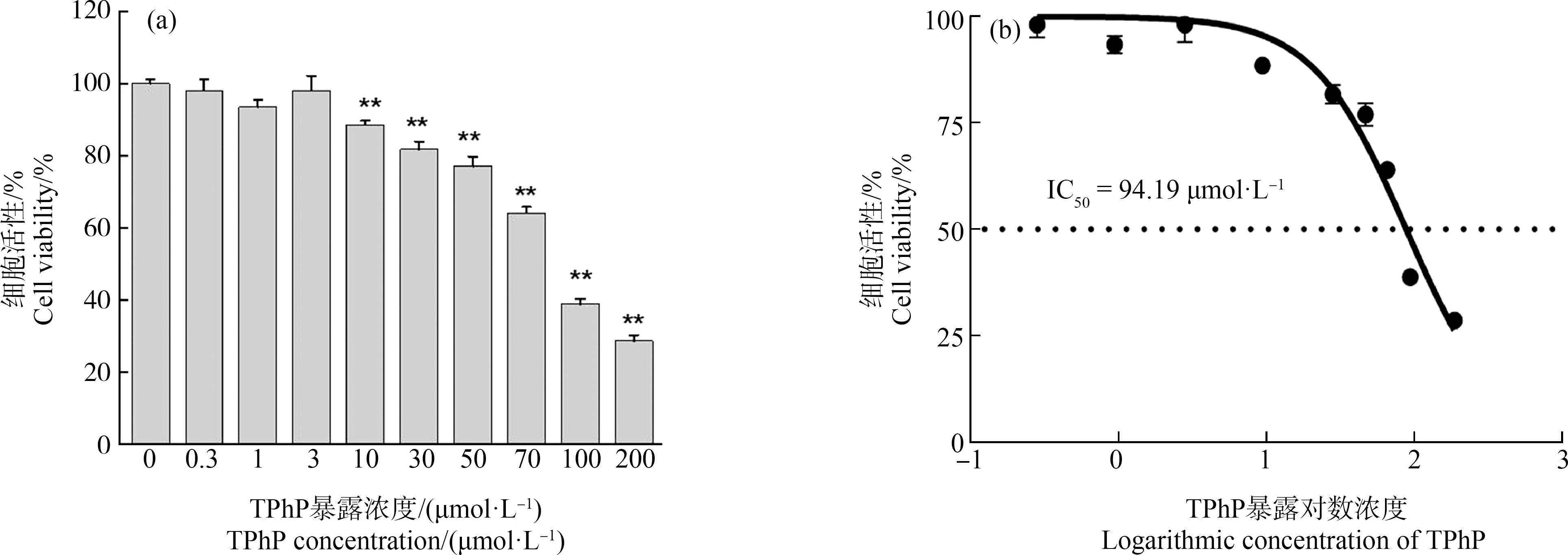

A549细胞经0、0.3、1、3、10、30、50、70、100和200 μmol·L-1的TPhP暴露24 h后,经CCK-8方法进行细胞活性的分析。结果显示,10~200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组的A549细胞活性显著降低,分别为对照组的88.4%、81.6%、76.9%、63.9%、38.8%和28.6%,其他各剂量组的肺细胞活性没有受到显著影响(图1(a))。利用非线性回归方法分析得出TPhP的IC50为94.19 μmol·L-1(图1(b))。

图1 磷酸三苯酯(TPhP)作用A549细胞24 h后对细胞活性的影响

注:图(a)为A549细胞经50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露后的细胞活性(%),每个值代表3次重复实验的平均值±标准差;“*”代表不同剂量下与对照组相比有显著性差异(**P<0.01)。

Fig. 1 Effect of triphenyl phosphate (TPhP) on cell viability in A549 cells after 24 h treatment

Note: Figure (a), cell viability (%) induced by 50, 100 and 200 μmol·L-1 TPhP in A549 cells, and results are means±SD of three replicate experiments; “*” represents the significant difference between the control group and the TPhP treatment groups (Compared with the control, ** P<0.01).

2.2 TPhP对A549细胞核形态的影响

高内涵分析系统可以对荧光标记的细胞核进行多参数分析,包括细胞核的形态、细胞核的均匀程度及细胞核的碎片化程度。细胞核的均匀程度可以通过细胞核的荧光强度来表征,而细胞核碎片化程度可以通过细胞核荧光强度的变异系数(coefficient of variation, CV值)进行评估。以Hoechst 33342标记细胞核,通过荧光成像及高内涵分析系统进行定量分析,获得细胞核多参数的值,以参数变化率的百分值作图,结果如图2所示。与对照组相比,随着TPhP作用浓度的增加,细胞核变化程度随之增加。在50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组中,细胞核面积显著增加(P<0.05),且与浓度呈正向的剂量-效应关系;50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组的细胞核亮度降低(P<0.05),说明细胞核的均匀程度降低;100 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组的细胞核荧光强度变异系数增大,表明细胞核碎片化程度加剧(P<0.01)。

图2 磷酸三苯酯(TPhP)作用A549细胞24 h后细胞核参数的变化

注:A549细胞经50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露后的细胞核参数变化率(%),每个值代表3次重复实验的平均值±标准差;“*”代表不同剂量下与对照组相比有显著性差异(*P<0.05, **P<0.01)。

Fig. 2 Change rate of cell nuclear parameters in A549 cells after 24 h treatment of triphenyl phosphate (TPhP)

Note: Change rate of nuclear parameters (%) induced by 50, 100 and 200 μmol·L-1 TPhP in A549 cells, and results are means±SD of three replicate experiments; “*” represents the significant difference between the control group and the TPhP treatment groups (Compared with the control, *P<0.05 and **P<0.01).

2.3 TPhP对A549细胞线粒体纹理结构的影响

用Mito Tracker Green荧光探针标记线粒体(图3(a)),利用高内涵纹理分析模块,对细胞线粒体的纹理结构及线粒体质量进行评估,以参数变化率的百分值作图。由图3(b)可知,与对照组相比,在100 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组中,线粒体数量显著增加(P<0.01),分别超过对照组数量的128.9%和72.6%,而在50 μmol·L-1 TPhP组,线粒体数量没有显著性变化;在100 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组中,线粒体的面积显著降低(P<0.01),降幅分别为对照组的16.4%和15.0%;对线粒体质量进行评估,发现50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组中,线粒体质量均呈下降趋势(P<0.01),分别降低15.8%、44.1%和32.8%,其中100 μmol·L-1组的线粒体损伤程度最严重。

图3 磷酸三苯酯(TPhP)作用A549细胞24 h后线粒体纹理结构的变化

注:图(a)中Control为DMSO对照组,TPhP为100 μmol·L-1 TPhP组,Hoechst 33342标记细胞核,Mito Tracker Green标记线粒体;图(b)为A549细胞经50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露后的线粒体纹理结构变化率(%),每个值代表3次重复实验的平均值±标准差;“*”代表不同剂量下与对照组相比有显著性差异(*P<0.05, **P<0.01)。

Fig. 3 Change rate of mitochondrial network structure in A549 cells after 24 h treatment of triphenyl phosphate (TPhP)

Note: In figure (a), Control means DMSO treatment group, TPhP means 100 μmol·L-1 TPhP treatment group; nucleus was labeled with Hoechst 33342 and mitochondria was labeled with Mito Tracker Green; in figure (b), change rate of mitochondrial network structure (%) induced by 50, 100 and 200 μmol·L-1 TPhP in A549 cells, and results are means±SD of three replicate experiments; “*” represents the significant difference between the control group and the TPhP treatment groups (Compared with the control, *P<0.05 and **P<0.01).

2.4 TPhP对A549细胞内活性氧(ROS)水平、NMP和MMP的影响

以CM-H2DCFDA、TOTO-3和JC-1分别标记ROS(图4(a))、NMP(图4(b))和MMP(图4(c)),通过荧光成像及高内涵分析系统进行定量分析,以参数变化率的百分值作图,结果如图4(d)所示。与对照组相比,TPhP暴露组的ROS水平显著升高(P<0.05),在100 μmol·L-1组达到最高水平,达到对照组的184.7%;在100 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组中,NMP显著增加(P<0.01),50 μmol·L-1 TPhP组没有显著性变化;在50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组中,MMP显著降低(P<0.01),分别降低35.3%、49.5%和61.6%,且与浓度呈一定的剂量-效应关系。

图4 磷酸三苯酯(TPhP)作用A549细胞24 h后活性氧(ROS)、核膜通透性(NMP)和线粒体膜电位(MMP)的变化

注:图(a)、图(b)和图(c)中Control为DMSO对照组,TPhP为100 μmol·L-1 TPhP组;图(a)和图(b)中Hoechst 33342标记细胞核,CM-H2DCFDA标记ROS,TOTO-3标记NMP;图(c)中Hoechst 33342标记细胞核,JC-1标记MMP;JC-1以聚集体形式存在时,呈红色荧光(MMP升高);JC-1以单体形式存在时,呈绿色荧光(MMP降低);图(d)为A549细胞经50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露后的ROS、NMP和MMP变化率(%),每个值代表3次重复实验的平均值±标准差;“*”代表不同剂量下与对照组相比有显著性差异(*P<0.05, **P<0.01)。

Fig. 4 Change rate of reactive oxygen species (ROS), nuclear membrane permeability (NMP) and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) in A549 cells after 24 h treatment of triphenyl phosphate (TPhP)

Note: In figure (a), (b) and (c), Control means DMSO treatment group, TPhP means 100 μmol·L-1 TPhP treatment group; in figure (a) and (b), nucleus was labeled with Hoechst 33342, ROS was labeled with CM-H2DCFDA, NMP was labeled with TOTO-3; in figure (c), nucleus was labeled with Hoechst 33342 and MMP was labeled with JC-1; red fluorescence represents the aggregate of JC-1; green fluorescence represents monomer of JC-1; in figure (d), change rate of ROS, NMP and MMP (%) induced by 50, 100 and 200 μmol·L-1 TPhP in A549 cells; results are means±SD of three replicate experiments; “*” represents the significant difference between the control group and the TPhP treatment groups (Compared with the control, *P<0.05 and **P<0.01).

2.5 TPhP对A549细胞pH2AX和细胞色素C表达量的影响

由图5(a)和5(c)可知,与对照组相比,100 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组中细胞内pH2AX含量显著增加(P<0.01),在200 μmol·L-1组达到最高水平,含量增加57.6%,表明TPhP作用可诱导细胞内DNA的损伤;由图5(b)和5(c)可知,在100 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组中,细胞色素C的含量显著增加(P<0.05),表达量分别增加16.9%和13.8%。在50 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组中,pH2AX和细胞色素C的蛋白表达量均没有显著性变化。

图5 磷酸三苯酯(TPhP)作用A549细胞24 h后磷酸化H2AX(pH2AX)和细胞色素C蛋白表达量的变化

注:图(a)和图(b)中Control为DMSO对照组,TPhP为100 μmol·L-1 TPhP组;Hoechst 33342标记细胞核,pH2AX蛋白由抗pH2AX的一抗和Alexa Fluor Plus 555标记的二抗染色,细胞色素C蛋白由抗细胞色素C的一抗和Alexa Fluor Plus 488标记的二抗染色;图(c)为A549细胞经50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露后的pH2AX和细胞色素C变化率(%),每个值代表3次重复实验的平均值±标准差;“*”代表不同剂量下与对照组相比有显著性差异(*P<0.05, **P<0.01);pH2AX为磷酸化组蛋白H2AX。

Fig. 5 Change rate of protein expression of phosphorylated histones H2AX (pH2AX) and cytochrome C in A549 cells after 24 h treatment of triphenyl phosphate (TPhP)

Note: In figure (a) and (b), Control means DMSO treatment group, TPhP means 100 μmol·L-1 TPhP treatment group; nucleus was labeled with Hoechst 33342, pH2AX was stained with an anti-pH2AX primary antibody and an Alexa Fluor Plus 555-labeled secondary antibody, cytochrome C was stained with an anti-cytochrome C primary antibody and an Alexa Fluor Plus 488-labeled secondary antibody; in figure (c), change rate of pH2AX and cytochrome C (%) induced by 50, 100 and 200 μmol·L-1 TPhP in A549 cells, and results are means±SD of three replicate experiments; “*” represents the significant difference between the control group and the TPhP treatment groups (Compared with the control, *P<0.05 and **P<0.01); pH2AX means phosphorylated histones H2AX.

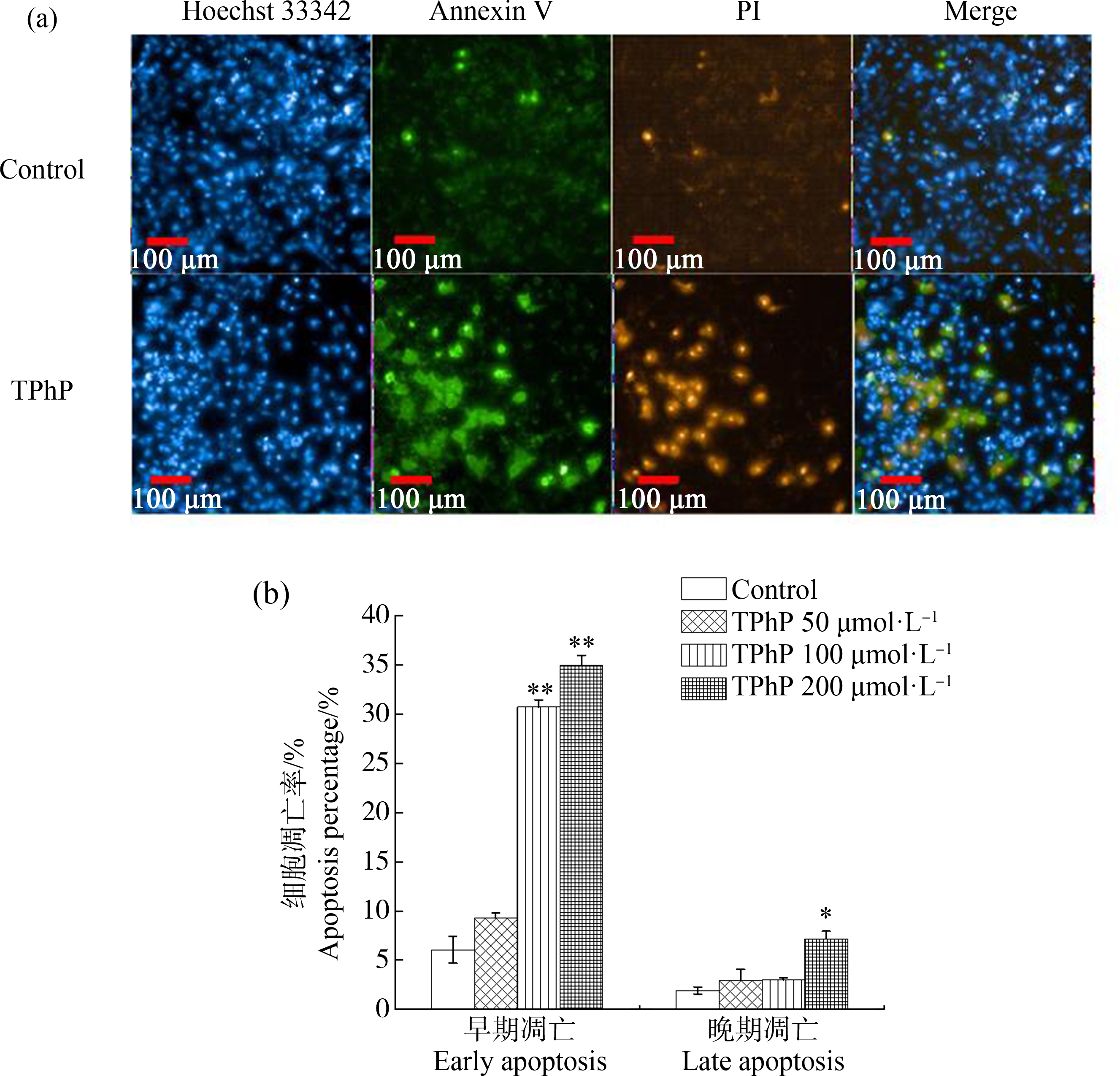

2.6 TPhP诱导A549细胞凋亡

采用Annexin V和PI双染法进一步检测TPhP对A549细胞凋亡的影响,当Annexin V染色明显,PI染色不明显时,表示细胞发生早期凋亡;当Annexin V和PI双染明显时,表示细胞发生晚期凋亡(图6(a))。由图6(b)可知,与对照组相比,100 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP处理A549细胞24 h,诱导细胞发生早期凋亡现象明显(P<0.01),引起的早期凋亡率分别为30.7%和34.9%,而细胞晚期凋亡率仅在200 μmol·L-1 TPhP组具有显著性升高(P<0.05),晚期凋亡率为7.2%,其他2个剂量组均没有显著性变化。

图6 磷酸三苯酯(TPhP)作用A549细胞24 h后细胞凋亡率的变化

注:图(a)中Control表示DMSO对照组,TPhP表示100 μmol·L-1 TPhP组;Hoechst 33342标记细胞核,Annexin V标记早期凋亡细胞,PI标记死亡细胞,Annexin V/PI双染标记晚期凋亡细胞;图(b)为A549细胞经50、100和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露后的细胞凋亡率(%),每个值代表3次重复实验的平均值±标准差;“*”代表不同剂量下与对照组相比有显著性差异(*P<0.05, **P<0.01)。

Fig. 6 Apoptosis percentage of A549 cells after 24 h treatment of triphenyl phosphate (TPhP)

Note: In figure (a), Control means DMSO treatment group, TPhP means 100 μmol·L-1 TPhP treatment group; early apoptotic cells are Annexin V positive and PI negative; necrotic cells are PI positive; late apoptotic cells are both Annexin V and PI positive; in figure (b), apoptosis percentage (%) induced by 50, 100 and 200 μmol·L-1 TPhP in A549 cells, results are means±SD of three replicate experiments; “*” represents the significant difference between the control group and the TPhP treatment groups (Compared with the control, *P<0.05 and ** P<0.01).

3 讨论(Discussion)

细胞的增殖活性和细胞活力是评价外界不利环境刺激对细胞毒性影响作用的关键指标。细胞活性结果显示,随着暴露浓度的增加,TPhP呈现明显的细胞毒性作用。较高浓度(50、70、100和200 μmol·L-1)的TPhP作用A549细胞24 h后,细胞的活性显著下降。与此相似,Canbaz等[13]发现浓度高于50 μmol·L-1的TPhP可导致小鼠树突状细胞的存活率显著降低,An等[12]的研究同样发现高浓度(150 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1)的TPhP作用A549细胞24 h,可导致细胞的存活率显著降低,然而,与本文的结果不同的是,50 μmol·L-1和100 μmol·L-1的TPhP对A549细胞存活率无明显影响。这种差异可能与受试细胞的不同来源(虽然遗传背景相同)、不同的传代次数和生理状态有关。利用非线性回归的方法,计算TPhP的IC50浓度为94.19 μmol·L-1,而中国仓鼠细胞和人肝细胞在TPhP处理24 h后的IC50分别为37 μmol·L-1和23.58 μmol·L-1[14-15]。综合以上的研究结果,可以发现,TPhP暴露不同细胞24 h后,IC50基本在几十μmol·L-1左右。由此推测,低浓度TPhP胁迫不会引起细胞毒性,而高浓度TPhP(≥几十μmol·L-1)存在明显的急性细胞毒性。

Hoechst 33342染色实验观察到,50 μmol·L-1的TPhP仅使A549细胞核面积增加,细胞核的其他参数均未出现显著性变化,而在高浓度(100 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1)TPhP组,细胞均出现核面积增加、核碎片化程度加剧和核膜通透性增加等典型的细胞核损伤现象。进一步的免疫荧光实验结果显示,100 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1 TPhP暴露组的pH2AX荧光强度相比对照组明显增强。pH2AX是DNA损伤的重要标志物,DNA双链断裂后会在DNA双链断裂点处形成pH2AX的聚集,它可以识别损伤后的DNA,在保持基因组的完整性及DNA损伤修复中具有重要作用[16]。因此,pH2AX荧光强度的增强,进一步说明TPhP作用引起细胞内DNA的损伤。与本文的研究结果相似,之前关于TPhP的研究同样发现,TPhP可导致A549细胞DNA损伤加剧及ROS水平升高,推测过多ROS的产生造成DNA损伤[12]。

线粒体是一种存在于大多数细胞中的由2层膜包被的细胞器,是细胞的动力工厂。在活细胞中,线粒体频繁地融合和分裂是细胞对抗内外环境的一种自我保护机制,这种相互拮抗的细胞功能导致线粒体在细胞中形成网状结构,线粒体在形态上表现为从分散的椭圆形或长管状到网络结构之间保持着此消彼长的动态平衡,这使得线粒体的动态变化极易受到细胞内外环境的影响[17]。Le等[18]的研究显示,5种OPFRs暴露AML-12肝细胞24 h,导致线粒体网络结构破坏,线粒体出现碎片化现象。目前,线粒体的碎裂被作为评估环境化学物质毒性效应的敏感生物标志物[19]。本文的结果显示,TPhP(100 μmol·L-1和200 μmol·L-1)使A549细胞线粒体纹理结构受到明显损伤,线粒体网络化程度下降,呈现碎裂或断裂状,说明TPhP具有较强的线粒体毒性。

氧化应激是许多外源性化学污染物引起细胞毒性的主要作用机制。线粒体是细胞活性氧产生的主要场所,也是氧化损伤的主要靶点[20]。细胞内过量ROS的产生会触发线粒体损伤。有研究表明,过量ROS可引起线粒体膜通透性转运孔道(mitochondrial permeability transition pore, MPTP)的开放[21],释放细胞色素C,激活半胱氨酸蛋白酶,最终导致细胞凋亡[22]。本研究对细胞内ROS水平、MMP及细胞色素C的定量分析结果显示,随着TPhP剂量的增加,细胞内ROS水平升高,MMP降低,细胞色素C含量升高,表明TPhP能诱导A549细胞的氧化应激反应,使线粒体结构受损,MMP下降,细胞色素C释放,最终导致细胞凋亡。

综上所述,本研究采用不同浓度TPhP处理A549细胞,发现较高浓度TPhP可抑制肺细胞的活力、损伤细胞核膜完整性、破坏线粒体网络结构和引起细胞DNA损伤,还可诱导线粒体途径释放细胞色素C,最终导致细胞凋亡。虽然实验中所设定的暴露浓度高于环境中的一般浓度,但TPhP在短期暴露中表现出的细胞毒性,对TPhP的毒性评价具有一定的参考价值。而环境浓度的TPhP长时间暴露对人体是否存在一定的健康风险,需要更多的研究加以确证。

[1] Yang J W, Zhao Y Y, Li M H, et al. A review of a class of emerging contaminants: The classification, distribution, intensity of consumption, synthesis routes, environmental effects and expectation of pollution abatement to organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs) [J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2019, 20(12): 2874

[2] Du J, Li H X, Xu S D, et al. A review of organophosphorus flame retardants (OPFRs): Occurrence, bioaccumulation, toxicity, and organism exposure [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2019, 26(22): 22126-22136

[3] Wei G L, Li D Q, Zhuo M N, et al. Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers: Sources, occurrence, toxicity and human exposure [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2015, 196: 29-46

[4] Feng L P, Ouyang F X, Liu L P, et al. Levels of urinary metabolites of organophosphate flame retardants, TDCIPP, and TPHP, in pregnant women in Shanghai [J]. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2016, 2016: 9416054

[5] He R W, Li Y Z, Xiang P, et al. Organophosphorus flame retardants and phthalate esters in indoor dust from different microenvironments: Bioaccessibility and risk assessment [J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 150: 528-535

[6] Chen Y X, Liu Q Y, Ma J, et al. A review on organophosphate flame retardants in indoor dust from China: Implications for human exposure [J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 260: 127633

[7] Li H R, La Guardia M J, Liu H H, et al. Brominated and organophosphate flame retardants along a sediment transect encompassing the Guiyu, China e-waste recycling zone [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 646: 58-67

[8] Wang R M, Tang J H, Xie Z Y, et al. Occurrence and spatial distribution of organophosphate ester flame retardants and plasticizers in 40 rivers draining into the Bohai Sea, North China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2015, 198: 172-178

[9] He C, Toms L L, Thai P, et al. Urinary metabolites of organophosphate esters: Concentrations and age trends in Australian children [J]. Environment International, 2018, 111: 124-130

[10] Gao D T, Yang J, Bekele T G, et al. Organophosphate esters in human serum in Bohai Bay, North China [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2020, 27(3): 2721-2729

[11] Chen X L, Zhao X Z, Shi Z X. Organophosphorus flame retardants in breast milk from Beijing, China: Occurrence, nursing infant’s exposure and risk assessment [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 771: 145404

[12] An J, Hu J W, Shang Y, et al. The cytotoxicity of organophosphate flame retardants on HepG2, A549 and Caco-2 cells [J]. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part A, Toxic/Hazardous Substances &Environmental Engineering, 2016, 51(11): 980-988

[13] Canbaz D, Logiantara A, van Ree R, et al. Immunotoxicity of organophosphate flame retardants TPHP and TDCIPP on murine dendritic cells in vitro [J]. Chemosphere, 2017, 177: 56-64

[14] Belcher S M, Cookman C J, Patisaul H B, et al. In vitro assessment of human nuclear hormone receptor activity and cytotoxicity of the flame retardant mixture FM 550 and its triarylphosphate and brominated components [J]. Toxicology Letters, 2014, 228(2): 93-102

[15] Wang X Q, Li F, Liu J L, et al. New insights into the mechanism of hepatocyte apoptosis induced by typical organophosphate ester: An integrated in vitro and in silico approach [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2021, 219: 112342

[16] Bonner W M, Redon C E, Dickey J S, et al. GammaH2AX and cancer [J]. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2008, 8(12): 957-967

[17] Eisner V, Picard M, Hajnóczky G. Mitochondrial dynamics in adaptive and maladaptive cellular stress responses [J]. Nature Cell Biology, 2018, 20(7): 755-765

[18] Le Y F, Shen H P, Yang Z, et al. Comprehensive analysis of organophosphorus flame retardant-induced mitochondrial abnormalities: Potential role in lipid accumulation [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 274: 116541

[19] Perdiz D, Oziol L, Poüs C. Early mitochondrial fragmentation is a potential in vitro biomarker of environmental stress [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 223: 577-587

[20] Li R W, Zhou P J, Guo Y Y, et al. Tris (1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate induces apoptosis and autophagy in SH-SY5Y cells: Involvement of ROS-mediated AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathways [J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2017, 100: 183-196

[21] Yu X L, Yin H, Peng H, et al. OPFRs and BFRs induced A549 cell apoptosis by caspase-dependent mitochondrial pathway [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 221: 693-702

[22] Kluck R M, Esposti M D, Perkins G, et al. The pro-apoptotic proteins, Bid and Bax, cause a limited permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane that is enhanced by cytosol [J]. The Journal of Cell Biology, 1999, 147(4): 809-822