1 微囊藻毒素的毒理与地质历史(Toxicological and geological history of microcystins)

1.1 微囊藻毒素的生物毒性

蓝藻是一种光自养的原核藻类,常见于世界各地的多种水环境中。蓝藻会在富营养化水体和特定环境条件下容易发生过度生长,形成水华。全球性气候变化带来的全球性升温、二氧化碳浓度升高、紫外线辐射增强、极端天气发生概率加大导致蓝藻在全球性气候变化过程中相对其他藻类更具有竞争优势,致使蓝藻水华发生的频度加大[1]。

水华蓝藻常常能够产生多种有毒性的藻毒素,微囊藻毒素(microcystins, MCs)是其中一种最广泛报道、也对人类健康威胁最大的蓝藻毒素。MCs普遍地由世界各地水环境中形成水华的蓝藻产生,如固氮的鱼腥藻(Anabaena)、节球藻(Nodularin),非固氮的微囊藻(Microcystis)、颤藻(Oscillatoria)等[2]。

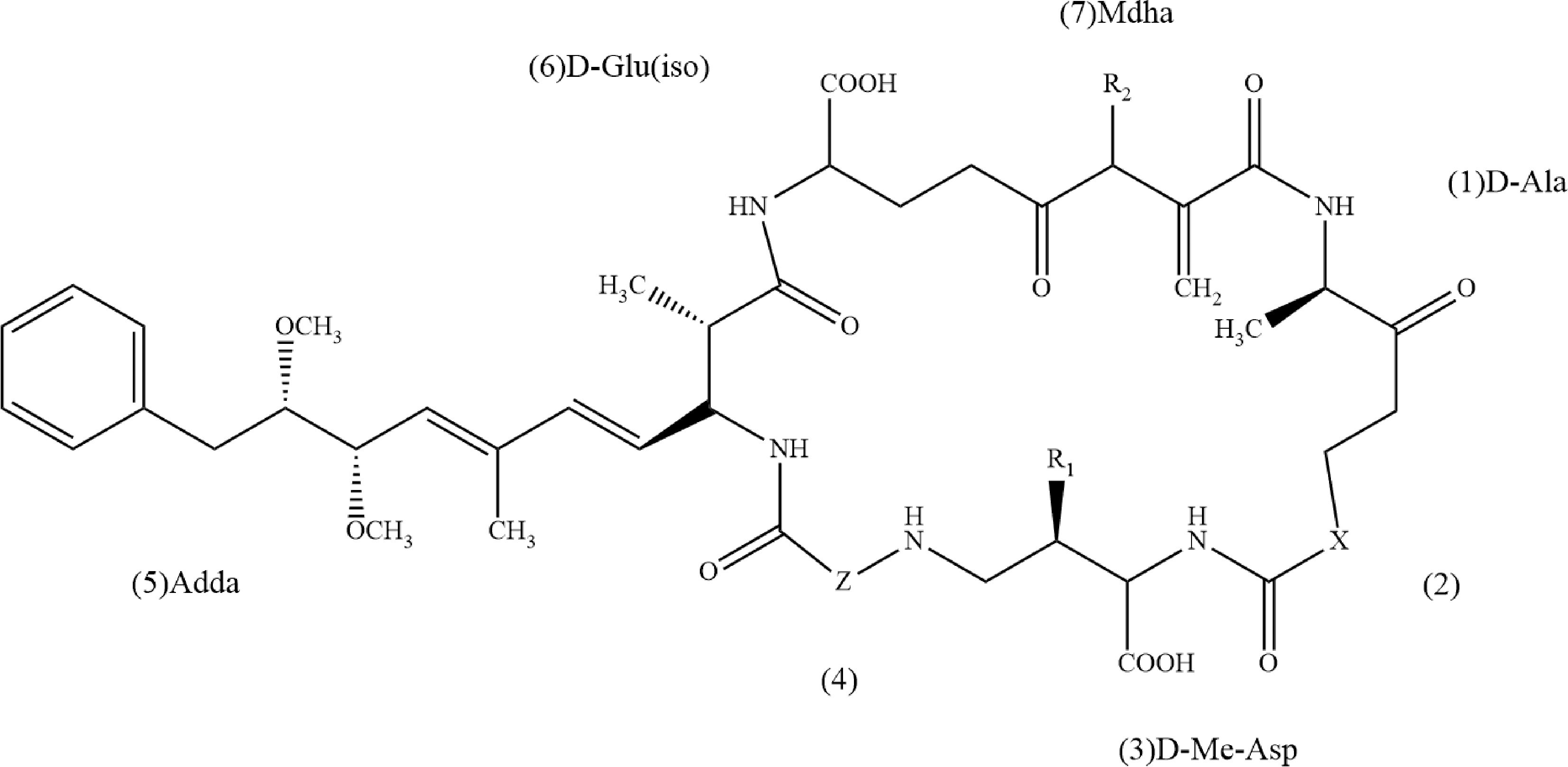

MCs的一般结构为环状(D-Ala1-X2-D-MeAsp3-Z4-Adda5-D-Glu6-Mdha7),其中X和Z是可变的L-氨基酸,D-Me-Asp代表D-β-甲基天冬氨酸,Adda是(2S,3S,8S,9S)-3-氨基-9-甲氧基-2,6,8-三甲基-10-苯基癸-4,6-二烯酸,Mdha是N-甲基脱氢丙氨酸(图1)。可变的亚基组合使得天然MCs存在超过100个异构体[3]。

图1 微囊藻毒素的一般结构

注:在MC-LR中,X表示L-亮氨酸,Z表示精氨酸,R1和R2表示CH3。

Fig. 1 General structure of microcystins

Note: In MC-LR, X stands for L-leucine, Z stands for arginine, and R1 and R2 stand for CH3.

MCs对周围环境中的植物存在一定的植物毒性。很多水生植物可以吸收微囊藻毒素并使其在体内累积,若长时间暴露于受藻毒素污染的水体,MCs会穿过根膜屏障,在植物组织内部转移并积累到不同的器官中,通过诱导氧化胁迫或抑制真核生物蛋白质的合成来影响水生植物的生物代谢(如生长、光合作用和酶系统)[4-5]。此外,MCs激活植物防御反应的同时也会导致光合作用速率降低[6]。但到目前为止,它们对植物细胞的毒性分子机制尚未明确。

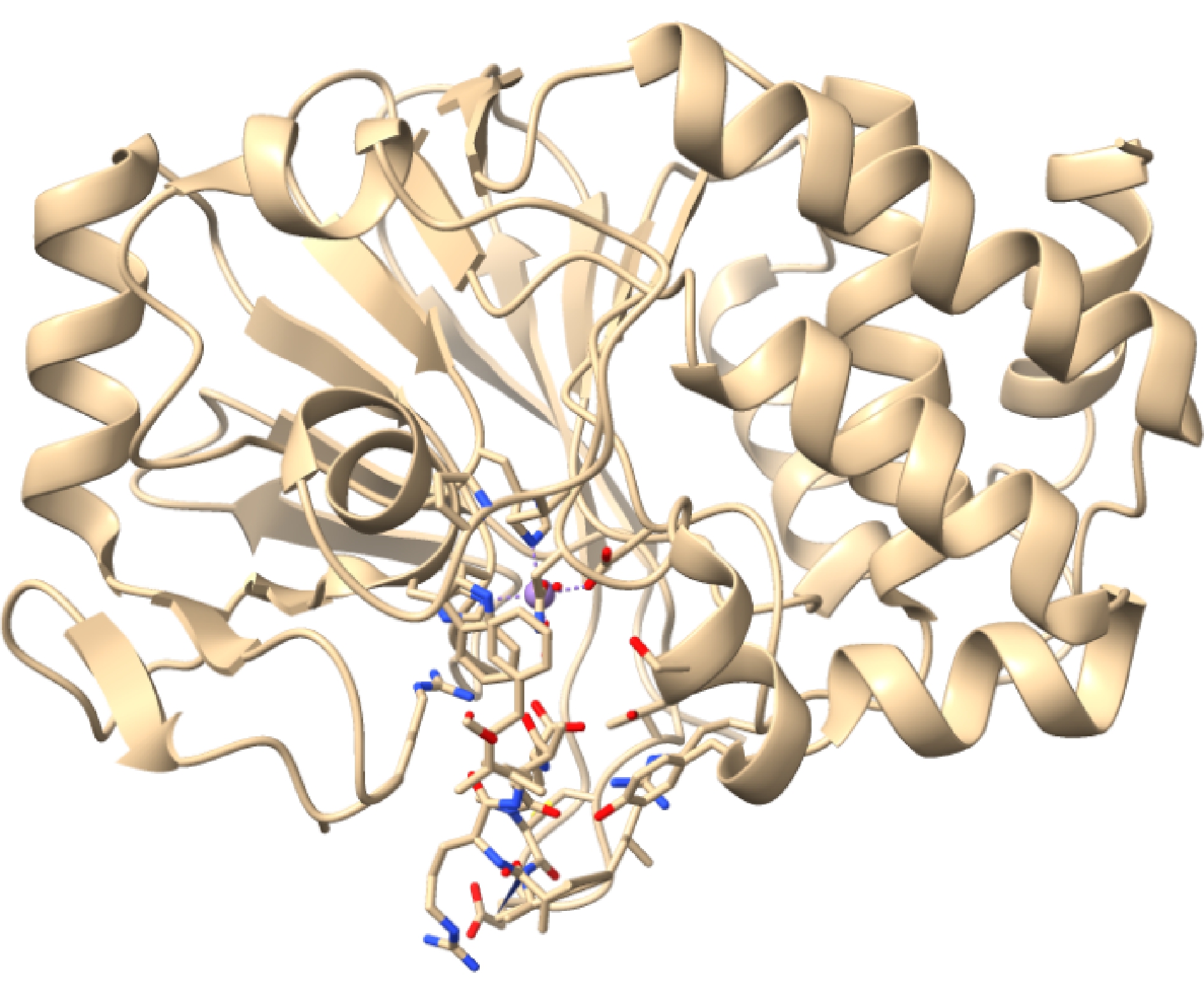

MCs对人类与哺乳动物能够产生强烈的毒性[7]。蛋白质的磷酸化和去磷酸化过程由磷酸化酶和激酶催化,能够调控细胞内的蛋白质活性,异常抑制这些酶对细胞的稳态会产生重大影响。MCs对丝氨酸/苏氨酸特异性蛋白磷酸酶的PP1和PP2A有很强的共价结合力,但对PP2B影响较小,MCs通过与PP1和PP2A结合抑制其活性(图2为LR型MCs与蛋白磷酸酶PP1的结合示意图)。MCs对动物的急性毒性也是通过抑制蛋白磷酸酶,导致蛋白的过度磷酸化和细胞骨架的改变,失去对促分裂素原活化蛋白激酶(mitogen activated protein kinase, MAPK)旁路的负调控作用,造成细胞形态的丧失,最终使肝内出血或肝功能不全[7]。除此之外,MCs还会通过诱导氧化应激反应、诱导中性粒细胞衍生趋化因子等分子机制,来诱导细胞凋亡,造成机体损害[8]。MCs的污染造成人类死亡的首次报道是1996年在巴西Caruaru市,医院的血液透析用水被MCs污染,造成至少76人发生肝功能衰竭症状,最终导致死亡[9]。近年来,MCs多次在全球范围内直接或间接影响人类健康。我国的太湖、长江等水域20多年来一直遭受蓝藻水华的困扰,甚至在2015年检测出太湖和巢湖地区的MCs超出国标2 600倍[10-11]。美国五大湖流域发生严重的蓝藻水华并造成牲畜死亡,其中占主导地位的产毒蓝藻就是产生MCs的微囊藻属[12]。近期,在希腊塞尔迈湾的紫贻贝(Mytilus galloprovincialis)养殖地也首次检测到MCs的存在[13]。因此,治理微囊藻水华及其释放的藻毒素污染是一个全球范围内的重要课题。

图2 MC-LR与蛋白磷酸酶PP1结合示意图

Fig. 2 The binding diagram of MC-LR and protein phosphatase PP1

1.2 地质历史上的藻毒素与生物大灭绝

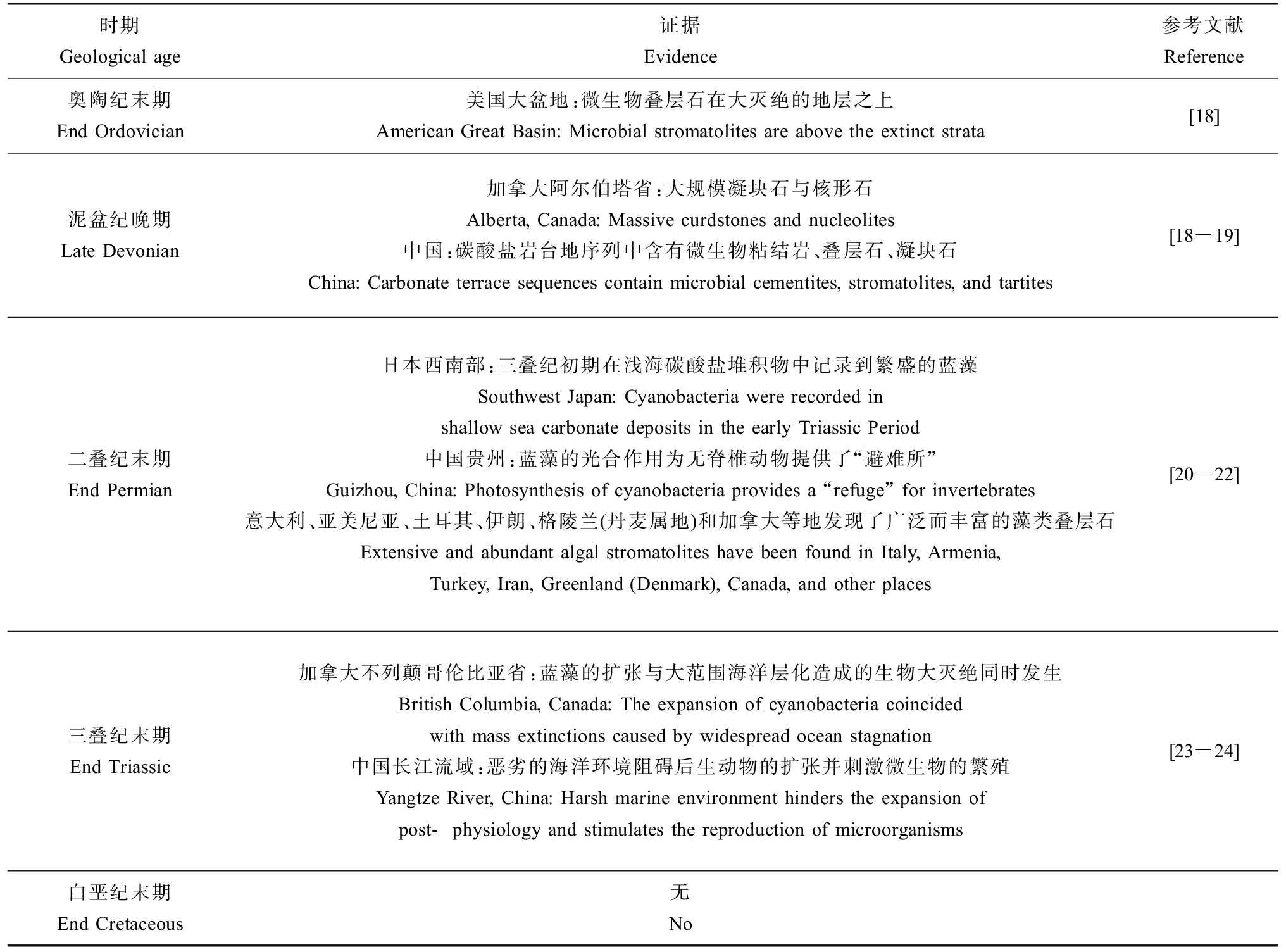

全球气候变化不仅会由人类活动而导致,在地球历史上流星撞击或火山喷发等自然原因或偶然事件也都会造成全球气温升高、海平面上升和CO2浓度升高等变化。这些气候变化被认为能够直接或间接地促进海洋和淡水环境中大规模藻类水华的发生[14-15]。通过对显生宙5次生物大灭绝时期的岩石记录进行研究(表1),发现除了白垩纪末期生物大灭绝(其主要归因于小行星撞击地球[16]),其他几次显生宙生物大灭绝事件都和叠层石丰度的增加存在一定关联性,而且与全球气温变化和海平面变化有关。对此,Castle和Rodgers[17]提出假说,频繁而大规模的藻类水华是造成水环境缺氧的主要原因,流星撞击或火山喷发引发的全球气候变化也促成了水华过程中藻毒素的大量释放,继而引起了显生宙的几次生物大灭绝。

表1 与5次生物大灭绝相关的藻类生物量增加的证据

Table 1 Evidence for increased microbial activity associated with mass extinctions

时期Geological age证据Evidence参考文献Reference奥陶纪末期End Ordovician 美国大盆地:微生物叠层石在大灭绝的地层之上American Great Basin: Microbial stromatolites are above the extinct strata[18]泥盆纪晚期Late Devonian加拿大阿尔伯塔省:大规模凝块石与核形石Alberta, Canada: Massive curdstones and nucleolites中国:碳酸盐岩台地序列中含有微生物粘结岩、叠层石、凝块石China: Carbonate terrace sequences contain microbial cementites, stromatolites, and tartites[18-19]二叠纪末期End Permian日本西南部:三叠纪初期在浅海碳酸盐堆积物中记录到繁盛的蓝藻Southwest Japan: Cyanobacteria were recorded in shallow sea carbonate deposits in the early Triassic Period中国贵州:蓝藻的光合作用为无脊椎动物提供了“避难所”Guizhou, China: Photosynthesis of cyanobacteria provides a “refuge” for invertebrates意大利、亚美尼亚、土耳其、伊朗、格陵兰(丹麦属地)和加拿大等地发现了广泛而丰富的藻类叠层石Extensive and abundant algal stromatolites have been found in Italy, Armenia, Turkey, Iran, Greenland (Denmark), Canada, and other places[20-22]三叠纪末期End Triassic 加拿大不列颠哥伦比亚省:蓝藻的扩张与大范围海洋层化造成的生物大灭绝同时发生British Columbia, Canada: The expansion of cyanobacteria coincided with mass extinctions caused by widespread ocean stagnation中国长江流域:恶劣的海洋环境阻碍后生动物的扩张并刺激微生物的繁殖Yangtze River, China: Harsh marine environment hinders the expansion of post-physiology and stimulates the reproduction of microorganisms[23-24]白垩纪末期End Cretaceous 无No

2 微囊藻毒素的生物学功能(Biological functions of microcystins)

目前的已有研究结果表明,MCs等藻毒素的产生,并非针对人类和哺乳动物。Rantala等[25]对MCs合成酶编码基因的系统发育分析表明,藻类合成MCs的能力要早于后生动物的起源,更是远远早于哺乳动物和人类的出现。因此可以确定,MCs对于哺乳动物和人类的毒性是偶然的,并不是该毒素原本的生物学功能。鉴于此,近20年来,国际上对MCs生物学功能的探索和争论持续至今[26-29]。

2.1 作为化感物质增强竞争力

由于蓝藻水华的有害影响在很大程度上是通过产生毒性化合物造成的,因此Wang等[30]认为水华是借助了这些藻毒素,才会达到如此高的细胞密度[31]。一种可能的机制是MCs能够保护蓝藻免受病原体、寄生虫或捕食者的侵害。这一机制得到了一些研究的支持,产毒藻株不太受捕食者的青睐,并且捕食者的存在也可能会诱导毒素的产生[32-33]。第2种可能的机制是藻毒素的主动释放可能会抑制竞争物种的生长或生存[33-34]。这种由化学物质介导的干扰性竞争现象被称为化感作用[35]。

有研究认为MCs的产生可能与多种浮游植物之间的化感作用有关,因此,MCs被认为是一种化感物质[36]。实验结果表明,MC-LR对莱氏衣藻(Chlamydomonas reinhardtii)细胞活力有明显的化感抑制作用。MC-LR在暴露开始阶段显著上调抗坏血酸过氧化物酶(APX)和过氧化氢酶(CAT)的蛋白丰度,并伴随着H2O2的过度积累。这表明MC-LR可以通过氧化损伤来抑制细胞活性[37]。铜绿微囊藻(Microcystis aeruginosa)的产毒藻株在营养充足和光照不受限制的条件下,与近头状尖胞藻(Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata)和镰形纤维藻(Ankistrodesmus falcatus)共培养时,2种藻的生物量均低于其单独培养时的生物量。这表明,藻毒素作为一种化感物质,使铜绿微囊藻在与其他物种竞争时处于有利地位[38]。在对铜绿微囊藻和韦森伯格氏微囊藻(Microcystis wesenbergii)之间的化感作用进行实验时,加入铜绿微囊藻的无细胞滤液对韦氏微囊藻的生长有抑制作用,说明铜绿微囊藻对韦森伯格氏微囊藻具有明显的化感抑制作用[39]。无论是微囊藻毒素纯品还是蓝藻提取物,都对多种受试硅藻(Fistulifera pelliculosa等)和红藻(Chroothece richteriana)的光合速率产生影响,进而抑制其生长[40]。微囊藻与鱼腥藻(Dolichospermum)的共培养存在化感抑制作用,但精确的生长效果会因菌株或种类而异,并受到营养条件的影响[41-42]。另外,长期暴露于MC-LR(49.1~98.3 μg·L-1)下,水生植物蒲草(Typha angustifolia Linn)受氧化胁迫严重,非气孔限制或气孔限制对光合作用系统的影响明显,导致光合作用速率下降[37]。MCs也会通过影响细胞膜功能、诱导氧化应激等机制,来抑制水生植物黄菖蒲(Iris pseudacorus L.)的生长[43]。

但对MCs与动物之间化感作用的研究仅在典型的水华高细胞浓度下发现显著影响,而进行较低细胞浓度条件实验时,没有检测到化感作用。除此以外也有一些研究结果否定了MCs作为抵抗动物摄食的化感物质的可能[44]。系统发育学研究发现,MCs的合成基因在蓝藻进化过程中一直存在,且早于后生动物的出现[45],于是否定了它抵御浮游动物摄食的功能[25,46]。因此,MCs作为化感物质来抵御动物摄食的观点并不被学界广泛接受。

2.2 参与调节光合作用

光照是MCs生物合成的一个重要影响因素,研究表明细胞需要活跃的光合作用才能产生更多的毒素,这说明MCs与光合作用之间存在一定的联系。

Zilliges等[47]研究发现,在高光强下MCs通过其N-甲基脱氢丙氨酸部分与蛋白磷酸酶靶标的半胱氨酸形成稳定的硫醚键,与卡尔文循环的光合活性酶结合发生相互作用,显示了野生型比突变株更加耐受高光强的优势。Wang等[48]为了研究铜绿微囊藻的光合作用速率与MCs产量之间的关系,在不同铁处理条件下对铜绿微囊藻进行了培养。实验验证,铁可以促进铜绿微囊藻的光合作用能力和促进MC-LR的产生,但不是以剂量依赖的方式。并且,光合作用能力与MCs产量呈显著正相关。由于铁的变化会通过影响电子传递链而抑制ATP的产生,进而改变微囊藻毒素合成基因的表达,这表明MCs的产生在很大程度上依赖于光合作用的氧化还原状态和能量代谢。García-Espín等[40]的实验结果显示,MC-LR纯品和蓝藻提取物都会促进或抑制被测藻类的光合作用活性。这种光合作用速率的变化可能与MCs通过产生更多的光合色素而影响光合作用系统有关。另外,在高光强的环境条件下,细胞会发生氧化应激,MCs可提高核酮糖-1,5-二磷酸羧化酶(ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, RuBisCO)的活性,降低胞内氧气浓度,耗费高光合速率积累的能量,从而避免氧化损伤[37, 47]。

2.3 有助于藻类适应环境变化

水温在3~27 ℃的范围内,蓝藻生物量在18 ℃以下随温度升高而增加,但随后随温度的进一步升高而迅速下降。环境中的MCs浓度与温度密切相关,且在20~25 ℃ 之间升高最多,这与蓝藻生物量的下降同时发生。并且产毒藻株比无毒藻株更容易在底泥中存活[49]。在富营养化的太湖,生物量受季节变化影响比较显著的蓝藻就包括微囊藻[50],其四季的相对丰度分别为19.6%、39.1%、75.6%和15.0%[51]。在夏季水温较高时,微囊藻提高光合速率会导致氧化应激,蓝藻生物量降低的同时产生大量MCs以维持自身生物量。Wang等[52]的研究也显示,大多数底栖微囊藻群落可以依赖MCs的存在以维持正常的光合作用速率,来度过冬季较为恶劣的环境。但Feng等[53]在研究复苏阶段毒素对微囊藻的影响时,并未发现高产毒微囊藻具有较高的复苏率,毒素含量较低的藻株反而复苏率略高。因此MCs有助于藻类越冬的观点还需要进行进一步研究。

由于人类生产活动造成碱性含盐废水排放量的增加,会对多种水生生物造成影响。Yu等[54]的实验结果表明,低碱性盐度(EC=2.5 mS·cm-1)有利于铜绿微囊藻的生长和MCs的合成和释放[55]。在中碱性盐度(EC=5 mS·cm-1)时,铜绿微囊藻能够激活碱性盐耐受机制,通过增加光合色素含量,但不影响细胞的抗氧化防御系统和细胞超微结构,来保护细胞免受碱性盐胁迫。因而增强铜绿微囊藻的存活率。但过量的碱性盐(EC=7.5 mS·cm-1)会对铜绿微囊藻产生毒性作用导致细胞死亡[56]。将产毒蓝藻培养在较低盐度水平(4 g·L-1 NaCl)时发现,这些蓝藻菌株可以诱导MCs的产生和ATP-柠檬酸裂合酶去磷酸化蛋白的表达[57]。由此可以说明,在一定的盐度范围内,产毒藻株可以通过调节MCs的释放,激活盐度耐受机制,来平衡并降低环境中盐度变化对自身的影响。

李伟等[58]通过模拟人工酸雨,发现铜绿微囊藻产毒藻株FACHB 905的细胞粒径在各个pH处理下都要明显高于无毒藻株FACHB 469;同时,酸雨处理导致藻体有效光化学效率显著降低,生长速率受到抑制,细胞死亡,FACHB 905表现出更强的抗逆性。推测MCs在对抗pH变化也发挥着一定的作用。

有研究发现,在湍流条件下,MCs浓度(胞内和胞外)显著增加,最大值是静水中的3.4倍。强烈的湍流会增加水流的剪切力,导致细胞机械损伤或细胞溶解,造成细胞破裂和包括毒素在内的细胞内物质泄漏。短期的湍流条件有利于产毒微囊藻的生长,也导致了微囊藻毒性的增加[59]。

2.4 有助于群落的形成

Kurmayer等[60]通过对野外单个群体微囊藻的尺寸大小及产毒量分析发现,微囊藻的产毒量与群体大小呈正相关。这表明MCs很有可能参与了微囊藻群体的形成过程。此外,MC-RR暴露会上调4种多糖的生物合成基因(capD、csaB、tagH和epsL)并显著增加细胞外多糖的产生[61]。Sedmak和Elersek[62]发现,MCs可以通过增加细胞浓度使细胞聚集;改变细胞通透性造成细胞体积增大;影响光合速率等多种机制参与水华的形成。

Kehr等[63]在铜绿微囊藻中发现的一种凝集素(microvirin, MVN),它参与了微囊藻的细胞间识别与粘附过程。添加外源MVN,可观察到MVN缺失突变株产生明显的细胞聚集。在铜绿微囊藻NIES-478的培养试验中,花生凝集素(peanut agglutinin, PNA)处理后的细胞表现出更高的细胞铁摄取率、MCs产量以及细胞外碳水化合物在细胞膜中的积累[64]。基于在mcyB突变细胞中不能检测到MVN等多种证据,表明MCs和MVN之间存在功能关联[65]。MCs可能作为一种信号分子,并以这种方式影响MVN及其结合配体的表达[66]。相关实验以是否降解胞外的MCs为对照,发现释放到胞外的毒素被降解后,微囊藻群落生物量减小约50%,证实了MCs对微囊藻群体形态的维持具有重要作用[61]。

2.5 作为信号分子传递信息

Phelan和Downing[67]将集胞藻(Synechocystis sp.) PCC6803暴露于MCs中,结果表明在与环境相关的浓度下,MCs能被不产生藻毒素的细胞吸收,并定位在类囊体膜上导致PS Ⅱ (photosystem Ⅱ)活性下降。RT-PCR结果表明,MCs的信号传导效应在很大程度上取决于用于培养的光照条件。pksⅠ~pksⅢ基因簇对外源MCs最敏感,而对微囊藻毒素合成基因表达的自诱导效应可以忽略不计,并且仅在光的临界阈值以上观察到[68]。

MCs在产毒细胞中对多种蛋白质具有调节的作用。微囊藻毒素合成基因缺失突变体ΔmcyB的蛋白质积累发生了显著变化,包括卡尔文循环中的几种酶、藻胆蛋白和2种依赖NADPH的还原酶(谷胱甘肽还原酶和硫氧还蛋白-二硫键还原酶)。MCs在细胞内能与这些蛋白质结合产生相互作用,并且在强光和氧化应激条件下,这种结合显著增强[47]。MCs对光合活性酶的作用在前文已有提及,是通过提高RuBisCO活性从而加快细胞光合速率。在类囊体膜中发现的MCs的百分比非常低,藻胆蛋白可能是具有这些寡肽结合位点的主要蛋白质,MCs通过与藻胆蛋白结合,增加其在微囊藻胞内溶胶的溶解度[69]。

Schatz等[46]研究则发现,被动机械裂解的细胞释放的MCs可被存活的细胞接收信息,进而显著提高微囊藻毒素合成基因的表达及含量以提高其他细胞的存活率,表明MCs可作为种内细胞信息交流物质,提高其他存活细胞的适应性[70]。甘南琴等[71]也指出MCs可能参与胞内信号传递与基因调控。

3 环境因素对藻毒素的影响(Effects of environmental factors on microcystins)

3.1 影响藻毒素产生与分布的环境因素

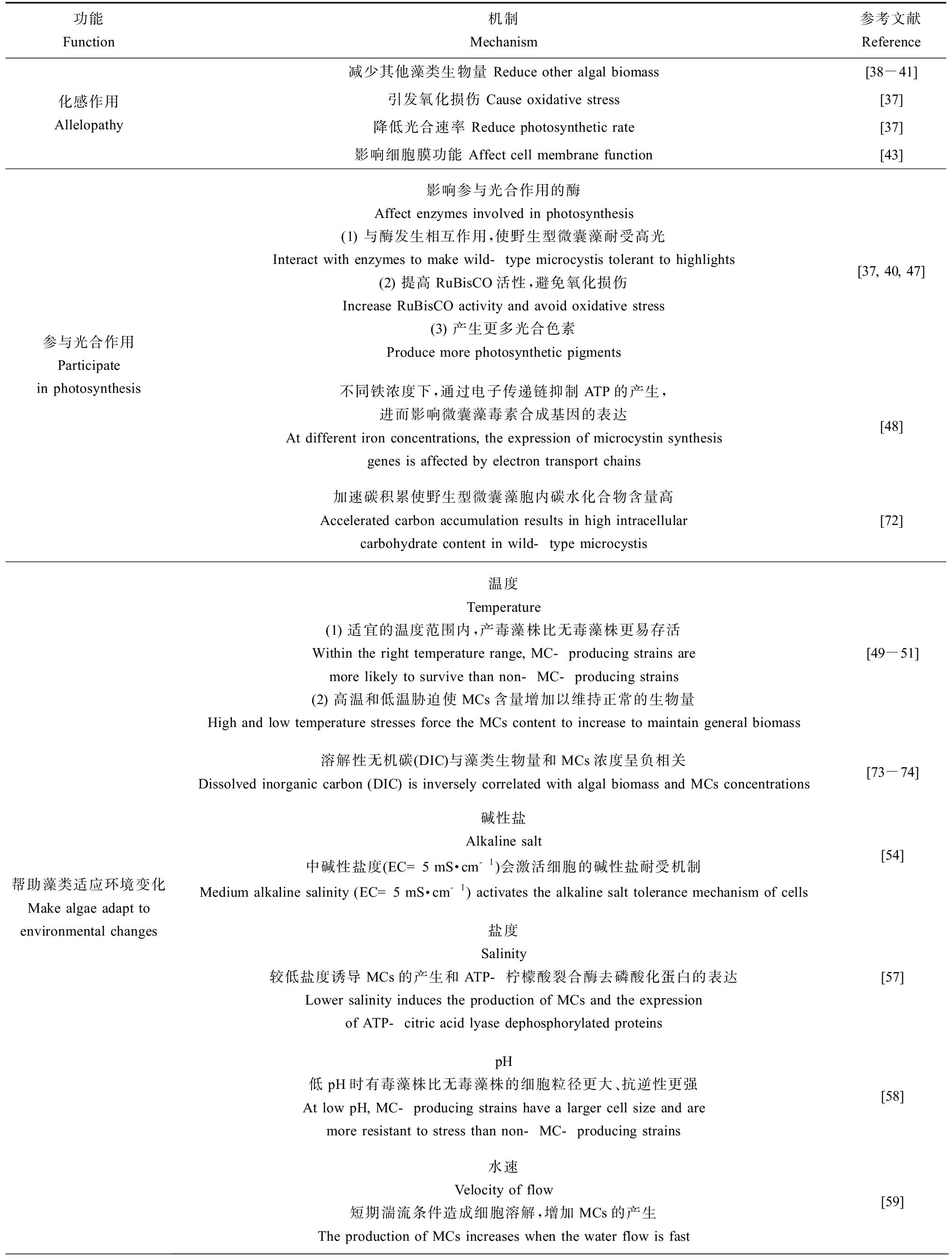

MCs的产生和环境变化有很强的关联。除了上述MCs能够帮助藻类适应环境变化(表2),反过来,MCs的生物合成也受到多种环境因素的影响,如光照[37, 76]、温度[49, 77]和营养物质[36, 76, 78]等。

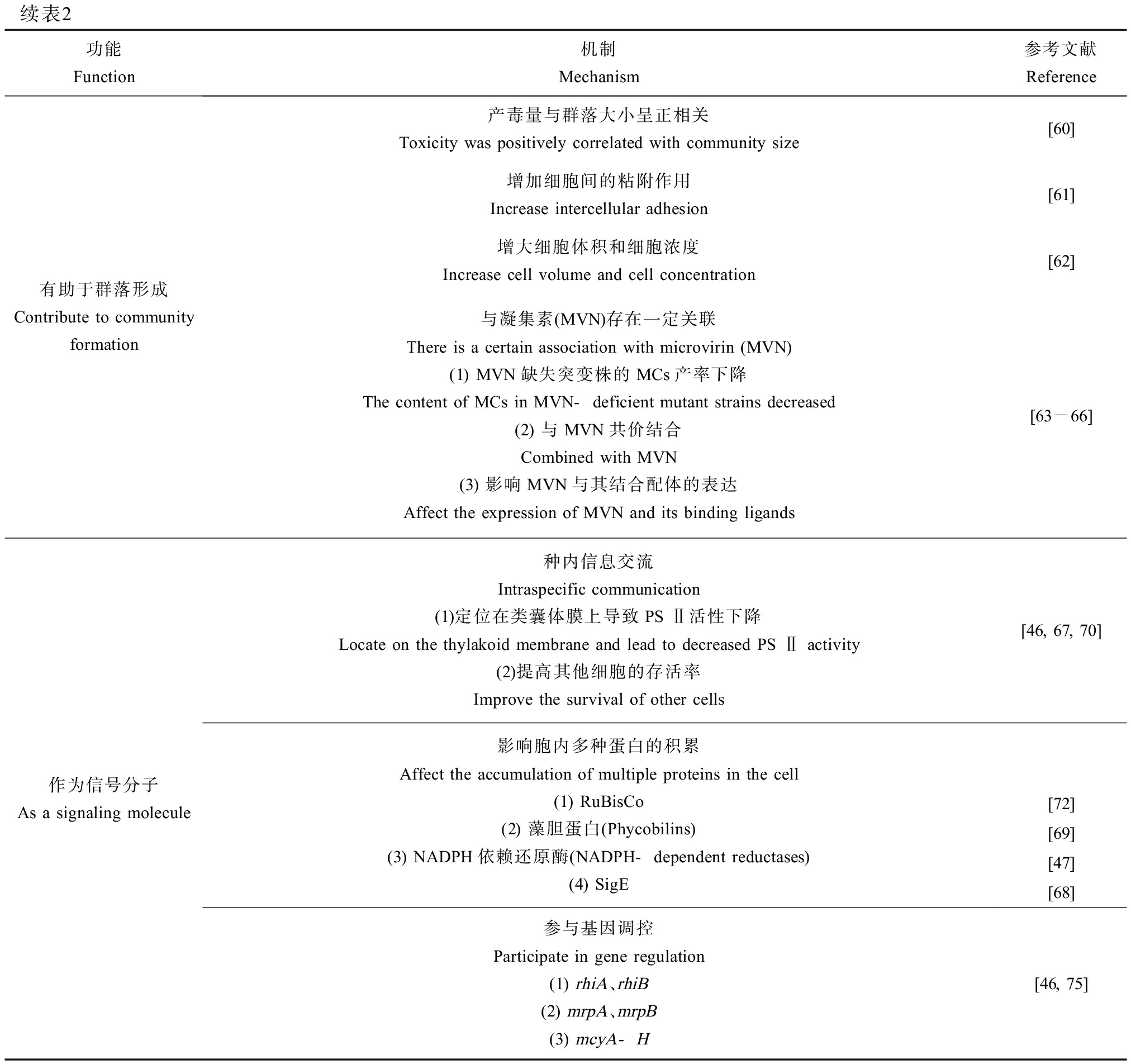

表2 微囊藻毒素的生物学功能及其机制

Table 2 Biological function and mechanism of microcystins

功能Function机制Mechanism参考文献Reference化感作用Allelopathy减少其他藻类生物量 Reduce other algal biomass[38-41]引发氧化损伤 Cause oxidative stress[37]降低光合速率 Reduce photosynthetic rate[37]影响细胞膜功能 Affect cell membrane function[43]参与光合作用Participate in photosynthesis影响参与光合作用的酶Affect enzymes involved in photosynthesis(1) 与酶发生相互作用,使野生型微囊藻耐受高光Interact with enzymes to make wild-type microcystis tolerant to highlights(2) 提高RuBisCO活性,避免氧化损伤Increase RuBisCO activity and avoid oxidative stress(3) 产生更多光合色素Produce more photosynthetic pigments[37, 40, 47]不同铁浓度下,通过电子传递链抑制ATP的产生,进而影响微囊藻毒素合成基因的表达At different iron concentrations, the expression of microcystin synthesis genes is affected by electron transport chains[48]加速碳积累使野生型微囊藻胞内碳水化合物含量高Accelerated carbon accumulation results in high intracellular carbohydrate content in wild-type microcystis[72]帮助藻类适应环境变化Make algae adapt to environmental changes温度Temperature(1) 适宜的温度范围内,产毒藻株比无毒藻株更易存活Within the right temperature range, MC-producing strains are more likely to survive than non-MC-producing strains(2) 高温和低温胁迫使MCs含量增加以维持正常的生物量High and low temperature stresses force the MCs content to increase to maintain general biomass溶解性无机碳(DIC)与藻类生物量和MCs浓度呈负相关Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) is inversely correlated with algal biomass and MCs concentrations碱性盐Alkaline salt中碱性盐度(EC=5 mS·cm-1)会激活细胞的碱性盐耐受机制Medium alkaline salinity (EC=5 mS·cm-1) activates the alkaline salt tolerance mechanism of cells盐度Salinity较低盐度诱导MCs的产生和ATP-柠檬酸裂合酶去磷酸化蛋白的表达Lower salinity induces the production of MCs and the expression of ATP-citric acid lyase dephosphorylated proteinspH低pH时有毒藻株比无毒藻株的细胞粒径更大、抗逆性更强At low pH, MC-producing strains have a larger cell size and are more resistant to stress than non-MC-producing strains水速Velocity of flow短期湍流条件造成细胞溶解,增加MCs的产生The production of MCs increases when the water flow is fast[49-51][73-74][54][57][58][59]

续表2功能Function机制Mechanism参考文献Reference有助于群落形成Contribute to community formation产毒量与群落大小呈正相关Toxicity was positively correlated with community size[60]增加细胞间的粘附作用Increase intercellular adhesion[61]增大细胞体积和细胞浓度Increase cell volume and cell concentration[62]与凝集素(MVN)存在一定关联There is a certain association with microvirin (MVN)(1) MVN缺失突变株的MCs产率下降The content of MCs in MVN-deficient mutant strains decreased(2) 与MVN共价结合Combined with MVN(3) 影响MVN与其结合配体的表达Affect the expression of MVN and its binding ligands[63-66]作为信号分子As a signaling molecule种内信息交流Intraspecific communication(1)定位在类囊体膜上导致PS Ⅱ活性下降Locate on the thylakoid membrane and lead to decreased PS Ⅱ activity(2)提高其他细胞的存活率Improve the survival of other cells影响胞内多种蛋白的积累Affect the accumulation of multiple proteins in the cell (1) RuBisCo(2) 藻胆蛋白(Phycobilins)(3) NADPH依赖还原酶(NADPH-dependent reductases)(4) SigE参与基因调控Participate in gene regulation(1) rhiA、rhiB(2) mrpA、mrpB(3) mcyA-H [46, 67, 70][72][69][47][68][46, 75]

注:NADPH是还原型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸。

Note: NADPH is nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

光照会直接影响微囊藻毒素合成基因的表达。紫外线照射可导致DNA、蛋白质或脂质的直接损伤,以及活性氧的积累,导致分子和细胞损伤。相比之下,却可导致MCs、氰肽蛋白等蛋白的产量增加。铜绿微囊藻暴露在逐渐增加的光强下或改变光质,MCs的胞外浓度增加[79]。紫外光照射不仅直接作用于膜系统的脂质并引起超微结构变化,而且对OEC和D1蛋白造成伤害,从而导致PS Ⅱ失活,同时可能通过氧化损伤来降解细胞内和细胞外的MCs[80]。

一项比较铜绿微囊藻在3种不同温度(20、26和32 ℃)下产生藻毒素的研究表明,随着温度的升高,MC-LR的水平不断升高。此外,铜绿微囊藻的产毒菌株在20 ℃以上时更具竞争力[81]。温度升高10 ℃会显著增加微囊藻毒素合成基因mcyB表达,从而增加MCs的合成[82]。温度的直接或间接影响是蓝藻群落产生的毒素空间分布、浓度的主要驱动因素。广义线性模型表明,毒素多样性指数随纬度的增大而增大,随水体稳定性的增大而减小。随着全球变暖的持续,湖泊温度升高的直接和间接影响将推动全球范围内蓝藻毒素分布的变化,可能会增加一些产毒物种或菌株的优势[81, 83]。Taranu等[84]的实验证实,毒性较大的MC-LA和MC-LR的水平与气候因素相关,在中风和频繁降雨的中低营养水体显示MC-LA的百分比较高,而温暖、营养丰富的条件显示MC-LR和MC-RR的百分比较高。

淡水水体中的蓝藻有害水华主要归因于水体富营养化,水体中的氮、磷含量也会对MCs有着一定的直接或间接影响。增加氮的供应将导致MCs产量增加,中低剂量(1~3 mg·L-1·周-1)的氮水平促进了有毒蓝藻在湖泊中的优势地位以及MCs浓度的升高[85]。无论氮的形态如何,较低的碳氮比培养基都会使微囊藻产生更高的MC-LR浓度[86]。产毒藻株的MCs产量与太湖中氨氮(NH3-N)浓度呈正相关,与洋河中总磷(TP)、总溶解磷(TDP)和磷酸盐(PO4-P)浓度呈正相关。这表明,影响太湖有毒蓝藻水华的主要营养因子是氮,而洋河则是磷[87]。

3.2 全球气候变化下藻毒素问题的凸显

蓝藻水华已成为全球最严重的水环境问题之一,已经对世界范围内的水生生态系统和人类公共健康造成了不可忽视的影响[88]。在全球气候不断变化的情况下,蓝藻水华的发生频率和危害范围也在日益增加,为防治藻毒素带来严峻的挑战[88-89]。

蓝藻水华产生的毒素可在水生生物中积累,并转移到更高的营养水平的生物,使牲畜和人类中毒,蓝藻水华被认为是一个严重危害人类健康的问题[90]。水华的形成在过去几十年里有所增加,主要原因是人类的各项生产活动造成营养物质过度释放到环境中,导致地表水富营养化;并且受人类生产生活的影响,全球气候不断变化,最明显的特征是全球平均气温上升,二氧化碳等温室气体水平升高。由此导致的地表水温升高和海洋碱度流失(海洋酸化),也是产毒藻类的生物量随着全球气候变化的趋势而增加的主要原因[91]。当今全球气候变化的趋势,除了内陆淡水水体,根据地质历史上的发展规律,气候变化也会对蓝藻毒素的产生有直接相关的影响并对海洋环境安全和人类健康造成潜在的威胁。

由于水温升高进一步加剧了水体层化,延长了层化期的持续时间,不仅增加了水华的次数,也增加了水华的持续时间。气温上升也可能会促进有毒蓝藻的优势地位[92],从而增加水生生物和人类对蓝藻毒素的潜在暴露。例如在波罗的海,由于温度是决定水华发生和强度的主要因素,产生节球藻毒素的泡沫节球藻(Nodularia spumigena)的相对比例增加,并在水华中占据主要优势[70]。Bui等[93]发现,在野外种群中,较高的温度(>27 ℃)可能会促进产毒微囊藻细胞的生长速度,从而导致产毒藻株的比例增加。

4 当今全球气候变化对藻毒素功能研究的启示(Implications of the global climate change for the study of the function of microcystins)

有大量学者认为,当今地球正处于第6次生物大灭绝的过程中[94-95]。全球气候变化和水华频繁暴发是目前人类纪的一个明显的全球性现象,这与上述的几次显生宙生物大灭绝有相似之处。上述假说[17]是危言耸听,还是确有可能,目前国际上讨论甚少,本文不作评判,但是全球气候变化引起蓝藻水华暴发的趋势以及藻毒素对我国人民健康的危害[88-89],确实需要引起我们的高度重视。

本文综述了近年来关于MCs的各种生物学功能的研究进展以及有关该毒素对于蓝藻本身来说的真正原本生物学功能的学术观点,但是在国际上仍然没有获得一致的意见。在众说纷纭中,期待有更加具有说服力的、在分子生化层面上的关于MCs原本生物学功能的研究成果。加强对MCs原本生物学功能的研究,无疑将对人们理解水华的发生机制以及控制藻毒素对人类健康的威胁,起到积极作用。

[1] 沈强, 胡菊香. 全球气候变化下的长江流域蓝藻水华暴发趋势[C]// 中国水利学会. 中国原水论坛专辑. 宁波: 中国水利学会, 2010: 359-360

[2] 谢平. 微囊藻毒素对人类健康影响相关研究的回顾[J]. 湖泊科学, 2009, 21(5): 603-613

Xie P. A review on the studies related to the effects of microcystins on human health [J]. Journal of Lake Sciences, 2009, 21(5): 603-613 (in Chinese)

[3] Fontanillo M, Köhn M. Microcystins: Synthesis and structure-activity relationship studies toward PP1 and PP2A [J]. Bioorganic &Medicinal Chemistry, 2018, 26(6): 1118-1126

[4] Redouane E M, El Amrani Zerrifi S, El Khalloufi F, et al. Mode of action and fate of microcystins in the complex soil-plant ecosystems [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 225: 270-281

[5] 靳红梅, 常志州. 微囊藻毒素对陆生植物的污染途径及累积研究进展[J]. 生态学报, 2013, 33(11): 3298-3310

Jin H M, Chang Z Z. The pollution way of microcystins and their bioaccumulation in terrestrial plants: A review [J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2013, 33(11): 3298-3310 (in Chinese)

[6] 胡智泉, 李敦海, 刘永定, 等. 微囊藻毒素对水生生物的生态毒理学研究进展[J]. 自然科学进展, 2006, 16(1): 14-20

[7] Zhang S Y, Du X D, Liu H H, et al. The latest advances in the reproductive toxicity of microcystin-LR [J]. Environmental Research, 2021, 192: 110254

[8] Ma Y, Liu H H, Du X D, et al. Advances in the toxicology research of microcystins based on Omics approaches [J]. Environment International, 2021, 154: 106661

[9] Tamele I J, Vasconcelos V. Microcystin incidence in the drinking water of Mozambique: Challenges for public health protection [J]. Toxins, 2020, 12(6): 368

[10] Hu L L, Shan K, Lin L Z, et al. Multi-year assessment of toxic genotypes and microcystin concentration in northern Lake Taihu, China [J]. Toxins, 2016, 8(1): 23

[11] Yang Z, Kong F X, Zhang M. Groundwater contamination by microcystin from toxic cyanobacteria blooms in Lake Chaohu, China [J]. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2016, 188(5): 280

[12] Carmichael W W, Boyer G L. Health impacts from cyanobacteria harmful algae blooms: Implications for the North American Great Lakes [J]. Harmful Algae, 2016, 54: 194-212

[13] Kalaitzidou M P, Nannou C I, Lambropoulou D A, et al. First report of detection of microcystins in farmed Mediterranean mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis in Thermaikos Gulf in Greece [J]. Journal of Biological Research, 2021, 28(1): 8

[14] Koch M, Bowes G, Ross C, et al. Climate change and ocean acidification effects on seagrasses and marine macroalgae [J]. Global Change Biology, 2013, 19(1): 103-132

[15] Guinotte J M, Fabry V J. Ocean acidification and its potential effects on marine ecosystems [J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2008, 1134: 320-342

[16] Chiarenza A A, Farnsworth A, Mannion P D, et al. Asteroid impact, not volcanism, caused the end-Cretaceous dinosaur extinction [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2020, 117(29): 17084-17093

[17] Castle J W, Rodgers J H. Hypothesis for the role of toxin-producing algae in Phanerozoic mass extinctions based on evidence from the geologic record and modern environments [J]. Environmental Geosciences, 2011, 18(1): 58-60

[18] Mata S A, Bottjer D J. Microbes and mass extinctions: Paleoenvironmental distribution of microbialites during times of biotic crisis [J]. Geobiology, 2012, 10(1): 3-24

[19] Yao L, Aretz M, Chen J T, et al. Global microbial carbonate proliferation after the end-Devonian mass extinction: Mainly controlled by demise of skeletal bioconstructors [J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6(1): 1-9

[20] Foster W J, Lehrmann D J, Yu M Y, et al. Facies selectivity of benthic invertebrates in a Permian/Triassic boundary microbialite succession: Implications for the “microbialite refuge” hypothesis [J]. Geobiology, 2019, 17(5): 523-535

[21] Takahashi S, Yamakita S, Suzuki N. Natural assemblages of the conodont Clarkina in lowermost Triassic deep-sea black claystone from northeastern Japan, with probable soft-tissue impressions [J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2019, 524: 212-229

[22] Gliwa J, Ghaderi A, Leda L, et al. Aras Valley (northwest Iran):High-resolution stratigraphy of a continuous central Tethyan Permian-Triassic boundary section [J]. Fossil Record, 2020, 23(1): 33-69

[23] Sephton M, Amor K, Franchi I, et al. Carbon and nitrogen isotope disturbances and an end-Norian (Late Triassic) extinction event [J]. Geology, 2002, 30(12): 1119-1122

[24] Duan X, Shi Z Q, Chen Y L, et al. Early Triassic Griesbachian microbial mounds in the Upper Yangtze Region, southwest China: Implications for biotic recovery from the latest Permian mass extinction [J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(8): e0201012

[25] Rantala A, Fewer D P, Hisbergues M, et al. Phylogenetic evidence for the early evolution of microcystin synthesis [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004, 101(2): 568-573

[26] Babica P, Bláha L, Maršálek B. Exploring the natural role of microcystins—A review of effects on photoautotrophic organisms [J]. Journal of Phycology, 2006, 42(1): 9-20

[27] Kaplan A, Harel M, Kaplan-Levy R N, et al. The languages spoken in the water body (or the biological role of cyanobacterial toxins) [J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2012, 3: 138

[28] Omidi A, Esterhuizen-Londt M, Pflugmacher S. Still challenging: The ecological function of the cyanobacterial toxin microcystin—What we know so far [J]. Toxin Reviews, 2018, 37(2): 87-105

[29] Schatz D, Keren Y, Vardi A, et al. Towards clarification of the biological role of microcystins, a family of cyanobacterial toxins [J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 9(4): 965-970

[30] Wang S Q, Yang S Y, Zuo J, et al. Simultaneous removal of the freshwater bloom-forming cyanobacterium microcystis and cyanotoxin microcystins via combined use of algicidal bacterial filtrate and the microcystin-degrading enzymatic agent, MlrA [J]. Microorganisms, 2021, 9(8): 1594

[31] Waters M N, Brenner M, Curtis J H, et al. Harmful algal blooms and cyanotoxins in Lake Amatitlán, Guatemala, coincided with ancient Maya occupation in the watershed [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2021, 118(48): e2109919118

[32] Zi J M, Pan X F, MacIsaac H J, et al. cyanobacteria blooms induce embryonic heart failure in an endangered fish species [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2018, 194: 78-85

[33] Omidi A, Pflugmacher S, Kaplan A, et al. Reviewing interspecies interactions as a driving force affecting the community structure in lakes via cyanotoxins [J]. Microorganisms, 2021, 9(8): 1583

[34] Cao Q, Steinman A D, Wan X, et al. Combined toxicity of microcystin-LR and copper on lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 206: 474-482

[35] Budza ek G,

ek G, ![]() ńska-Wilczewska S, Klin M, et al. Changes in growth, photosynthesis performance, pigments, and toxin contents of bloom-forming cyanobacteria after exposure to macroalgal allelochemicals [J]. Toxins, 2021, 13(8): 589

ńska-Wilczewska S, Klin M, et al. Changes in growth, photosynthesis performance, pigments, and toxin contents of bloom-forming cyanobacteria after exposure to macroalgal allelochemicals [J]. Toxins, 2021, 13(8): 589

[36] Brêda-Alves F, de Oliveira Fernandes V, Cordeiro-Araújo M K, et al. The combined effect of clethodim (herbicide) and nitrogen variation on allelopathic interactions between Microcystis aeruginosa and Raphidiopsis raciborskii [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2021, 28(9): 11528-11539

[37] Chen G Y, Zheng Z H, Bai M X, et al. Chronic effects of microcystin-LR at environmental relevant concentrations on photosynthesis of Typha angustifolia Linn [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2020, 29(5): 514-523

[38] Hernández-Zamora M, Santiago-Martínez E, Martínez-Jerónimo F. Toxigenic Microcystis aeruginosa (cyanobacteria) affects the population growth of two common green microalgae: Evidence of other allelopathic metabolites different to cyanotoxins [J]. Journal of Phycology, 2021, 57(5): 1530-1541

[39] Yang J, Deng X R, Xian Q M, et al. Allelopathic effect of Microcystis aeruginosa on Microcystis wesenbergii: Microcystin-LR as a potential allelochemical [J]. Hydrobiologia, 2014, 727(1): 65-73

[40] García-Espín L, Cantoral E A, Asencio A D, et al. Microcystins and cyanophyte extracts inhibit or promote the photosynthesis of fluvial algae. Ecological and management implications [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2017, 26(5): 658-666

[41] Chia M A, Jankowiak J G, Kramer B J, et al. Succession and toxicity of Microcystis and Anabaena (Dolichospermum) blooms are controlled by nutrient-dependent allelopathic interactions [J]. Harmful Algae, 2018, 74: 67-77

[42] González-Pleiter M, Cirés S, Wörmer L, et al. Ecotoxicity assessment of microcystins from freshwater samples using a bioluminescent cyanobacterial bioassay [J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 240: 124966

[43] Wang N Y, Wang C. Effects of microcystin-LR on the tissue growth and physiological responses of the aquatic plant Iris pseudacorus L. [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2018, 200: 197-205

[44] Lu N, Sun Y F, Wei J J, et al. Toxic Microcystis aeruginosa alters the resource allocation in Daphnia mitsukuri responding to fish predation cues [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 278: 116918

[45] Henao E, Rzymski P, Waters M N. A review on the study of cyanotoxins in paleolimnological research: Current knowledge and future needs [J]. Toxins, 2019, 12(1): 6

[46] Schatz D, Keren Y, Vardi A, et al. Towards clarification of the biological role of microcystins, a family of cyanobacterial toxins [J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 9(4): 965-970

[47] Zilliges Y, Kehr J C, Meissner S, et al. The cyanobacterial hepatotoxin microcystin binds to proteins and increases the fitness of microcystis under oxidative stress conditions [J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(3): e17615

[48] Wang X, Wang P F, Wang C, et al. Relationship between photosynthetic capacity and microcystin production in toxic Microcystis aeruginosa under different iron regimes [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2018, 15(9): 1954

[49] Walls J T, Wyatt K H, Doll J C, et al. Hot and toxic: Temperature regulates microcystin release from cyanobacteria [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 610-611: 786-795

[50] Xue Q J, Steinman A D, Xie L Q, et al. Seasonal variation and potential risk assessment of microcystins in the sediments of Lake Taihu, China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 259: 113884

[51] Zhu C M, Zhang J Y, Nawaz M Z, et al. Seasonal succession and spatial distribution of bacterial community structure in a eutrophic freshwater Lake, Lake Taihu [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 669: 29-40

[52] Wang C B, Feng B, Tian C C, et al. Quantitative study on the survivability of Microcystis colonies in lake sediments [J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2018, 30(1): 495-506

[53] Feng B, Wang C B, Wu X Q, et al. Involvement of microcystins, colony size and photosynthetic activity in the benthic recruitment of Microcystis [J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2019, 31(1): 223-233

[54] Yu J, Zhu H, Shutes B, et al. Salt-alkalization may potentially promote Microcystis aeruginosa blooms and the production of microcystin-LR [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2022, 301: 118971

[55] Trung B, Vollebregt M E, Lürling M. Warming and salt intrusion affect microcystin production in tropical bloom-forming Microcystis [J]. Toxins, 2022, 14(3): 214

[56] Jia J M, Chen Q W, Wang M, et al. The production and release of microcystin related to phytoplankton biodiversity and water salinity in two cyanobacteria blooming lakes [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2018, 37(9): 2312-2322

[57] Walker D, Fathabad S G, Tabatabai B, et al. Microcystin levels in selected cyanobacteria exposed to varying salinity [J]. Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 2019, 11(4): 395-403

[58] 李伟, 杨雨玲, 黄松, 等. 产毒与不产毒铜绿微囊藻对模拟酸雨及紫外辐射的生理响应[J]. 生态学报, 2015, 35(23): 7615-7624

Li W, Yang Y L, Huang S, et al. Physiological responses of toxigenic and non-toxigenic strains of Microcystis aeruginosa to simulated acid rain and UV radiation [J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2015, 35(23): 7615-7624 (in Chinese)

[59] Zhou J, Qin B Q, Han X X, et al. Turbulence increases the risk of microcystin exposure in a eutrophic lake (Lake Taihu) during cyanobacterial bloom periods [J]. Harmful Algae, 2016, 55: 213-220

[60] Kurmayer R, Christiansen G, Chorus I. The abundance of microcystin-producing genotypes correlates positively with colony size in Microcystis sp. and determines its microcystin net production in Lake Wannsee [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(2): 787-795

[61] Gan N Q, Xiao Y, Zhu L, et al. The role of microcystins in maintaining colonies of bloom-forming Microcystis spp. [J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 14(3): 730-742

[62] Sedmak B, Elersek T. Microcystins induce morphological and physiological changes in selected representative phytoplanktons [J]. Microbial Ecology, 2006, 51(4): 508-515

[63] Kehr J C, Zilliges Y, Springer A, et al. A mannan binding lectin is involved in cell-cell attachment in a toxic strain of Microcystis aeruginosa [J]. Molecular Microbiology, 2006, 59(3): 893-906

[64] Takaara T, Sasaki S, Fujii M, et al. Lectin-stimulated cellular iron uptake and toxin generation in the freshwater cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa [J]. Harmful Algae, 2019, 83: 25-33

[65] 陈何舟, 左胜鹏, 秦伯强, 等. 微囊藻聚集与迁移机制的研究进展[J]. 环境科学与技术, 2019, 42(1): 142-149

Chen H Z, Zuo S P, Qin B Q, et al. Research progress in mechanism of Microcystis aggregation and migration [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2019, 42(1): 142-149 (in Chinese)

[66] Xiao M, Willis A, Burford M A, et al. Review: A meta-analysis comparing cell-division and cell-adhesion in Microcystis colony formation [J]. Harmful Algae, 2017, 67: 85-91

[67] Phelan R R, Downing T G. The localization of exogenous microcystin LR taken up by a non-microcystin producing cyanobacterium [J]. Toxicon, 2014, 89: 87-90

[68] Makower A K, Schuurmans J M, Groth D, et al. Transcriptomics-aided dissection of the intracellular and extracellular roles of microcystin in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806 [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2015, 81(2): 544-554

[69] Jüttner F, Lüthi H. Topology and enhanced toxicity of bound microcystins in Microcystis PCC 7806 [J]. Toxicon, 2008, 51(3): 388-397

[70] El-Shehawy R, Gorokhova E, Fernández-Pi as F, et al. Global warming and hepatotoxin production by cyanobacteria: What can we learn from experiments? [J]. Water Research, 2012, 46(5): 1420-1429

as F, et al. Global warming and hepatotoxin production by cyanobacteria: What can we learn from experiments? [J]. Water Research, 2012, 46(5): 1420-1429

[71] 甘南琴, 魏念, 宋立荣. 微囊藻毒素生物学功能研究进展[J]. 湖泊科学, 2017, 29(1): 1-8

Gan N Q, Wei N, Song L R. Recent progress in research of the biological function of microcystins [J]. Journal of Lake Sciences, 2017, 29(1): 1-8 (in Chinese)

[72] Meissner S, Steinhauser D, Dittmann E. Metabolomic analysis indicates a pivotal role of the hepatotoxin microcystin in high light adaptation of Microcystis [J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2015, 17(5): 1497-1509

[73] Yu L, Kong F X, Zhang M, et al. The dynamics of microcystis genotypes and microcystin production and associations with environmental factors during blooms in Lake Chaohu, China [J]. Toxins, 2014, 6(12): 3238-3257

[74] Zhang Y, Jiang H B, Liu S W, et al. Effects of dissolved inorganic carbon on competition of the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa with the green alga Chlamydomonas microsphaera [J]. European Journal of Phycology, 2012, 47(1): 1-11

[75] Dittmann E, Erhard M, Kaebernick M, et al. Altered expression of two light-dependent genes in a microcystin-lacking mutant of Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806 [J]. Microbiology, 2001, 147(Pt 11): 3113-3119

[76] Dai R H, Wang P F, Jia P L, et al. A review on factors affecting microcystins production by algae in aquatic environments [J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2016, 32(3): 51

[77] Santos A, Rachid C, Pacheco A B, et al. Biotic and abiotic factors affect microcystin-LR concentrations in water/sediment interface [J]. Microbiological Research, 2020, 236: 126452

[78] Schreidah C M, Ratnayake K, Senarath K, et al. Microcystins: Biogenesis, toxicity, analysis, and control [J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2020, 33(9): 2225-2246

[79] Jacinavicius F R, Geraldes V, Crnkovic C M, et al. Effect of ultraviolet radiation on the metabolomic profiles of potentially toxic cyanobacteria [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2021, 97(1): fiaa243

[80] Wang B L, Wang X, Hu Y W, et al. The combined effects of UV-C radiation and H2O2 on Microcystis aeruginosa, a bloom-forming cyanobacterium [J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 141: 34-43

[81] Evanthia M, Miquel L, Jutta F, et al. Temperature effects explain continental scale distribution of cyanobacterial toxins [J]. Toxins, 2018, 10(4): 156

[82] Scherer P I, Raeder U, Geist J, et al. Influence of temperature, mixing, and addition of microcystin-LR on microcystin gene expression in Microcystis aeruginosa [J]. MicrobiologyOpen, 2017, 6(1): e00393

[83] Savadova-Ratkus K, Mazur-Marzec H, ![]() J, et al. Interplay of nutrients, temperature, and competition of native and alien cyanobacteria species growth and cyanotoxin production in temperate lakes [J]. Toxins, 2021, 13(1): 23

J, et al. Interplay of nutrients, temperature, and competition of native and alien cyanobacteria species growth and cyanotoxin production in temperate lakes [J]. Toxins, 2021, 13(1): 23

[84] Taranu Z E, Pick F R, Creed I F, et al. Meteorological and nutrient conditions influence microcystin congeners in freshwaters [J]. Toxins, 2019, 11(11): 620

[85] Tanvir R U, Hu Z Q, Zhang Y Y, et al. Cyanobacterial community succession and associated cyanotoxin production in hypereutrophic and eutrophic freshwaters [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 290: 118056

[86] Wagner N D, Quach E, Buscho S, et al. Nitrogen form, concentration, and micronutrient availability affect microcystin production in cyanobacterial blooms [J]. Harmful Algae, 2021, 103: 102002

[87] Wang M, Shi W Q, Chen Q W, et al. Effects of nutrient temporal variations on toxic genotype and microcystin concentration in two eutrophic lakes [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2018, 166: 192-199

[88] 刘雪梅, 章光新. 气候变化对湖泊蓝藻水华的影响研究综述[J]. 水科学进展, 2022, 33(2): 316-326

Liu X M, Zhang G X. A review of studies on the impact of climate change on cyanobacteria blooms in lakes [J]. Advances in Water Science, 2022, 33(2): 316-326 (in Chinese)

[89] 王成林, 潘维玉, 韩月琪, 等. 全球气候变化对太湖蓝藻水华发展演变的影响[J]. 中国环境科学, 2010, 30(6): 822-828

Wang C L, Pan W Y, Han Y Q, et al. Effect of global climate change on cyanobacteria bloom in Taihu Lake [J]. China Environmental Science, 2010, 30(6): 822-828 (in Chinese)

[90] Singo A, Myburgh J G, Laver P N, et al. Vertical transmission of microcystins to Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) eggs [J]. Toxicon, 2017, 134: 50-56

[91] Gehringer M M, Wannicke N. Climate change and regulation of hepatotoxin production in cyanobacteria [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2014, 88(1): 1-25

[92] Dziallas C, Grossart H P. Increasing oxygen radicals and water temperature select for toxic Microcystis sp. [J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(9): e25569

[93] Bui T, Dao T S, Vo T G, et al. Warming affects growth rates and microcystin production in tropical bloom-forming Microcystis strains [J]. Toxins, 2018, 10(3): 123

[94] Wyner Y, DeSalle R. Distinguishing extinction and natural selection in the anthropocene: Preventing the Panda paradox through practical education measures: We must rethink evolution teaching to prevent misuse of natural selection to biologically justify today’s human caused mass extinction crisis [J]. BioEssays: News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, 2020, 42(2): e1900206

[95] Spalding C, Hull P M. Towards quantifying the mass extinction debt of the Anthropocene [J]. Proceedings Biological Sciences, 2021, 288(1949): 20202332