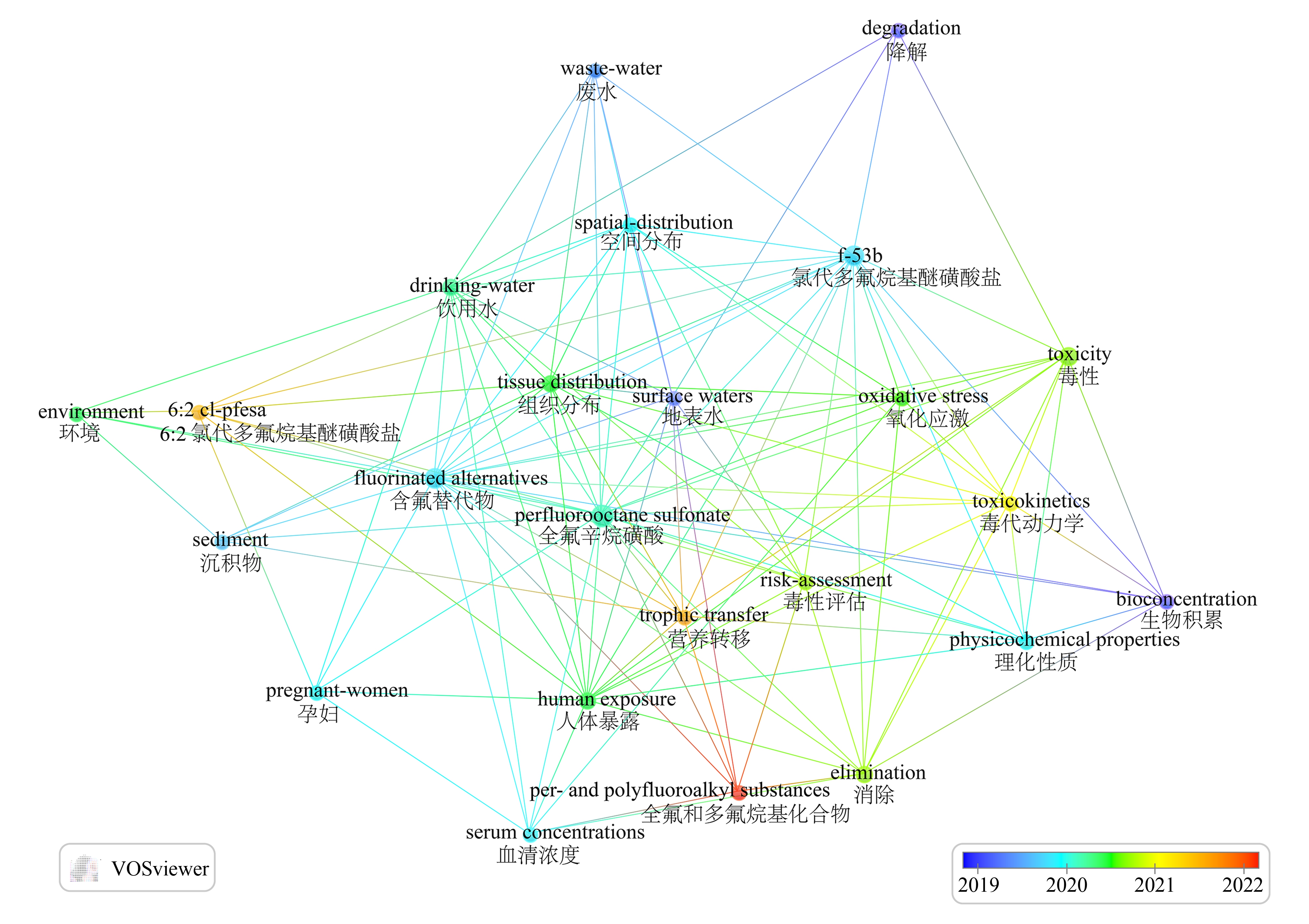

全氟辛烷磺酸盐(perfluorooctane sulfonate, PFOS)作为典型的全氟和多氟化合物(per- and polyfluoroalkylated substances, PFASs),具有许多独特的物理化学性质,包括疏水疏油、热稳定性、化学稳定性和表面活性,被广泛应用于工业和日常产品消费等领域[1]。同时PFOS表现出的高环境持久性、高生物积累性和长距离迁移特点,对环境和人类健康造成了威胁,2009年《关于持久性有机污染物的斯德哥尔摩公约》(简称POPs公约)第4次缔约方大会上,PFOS被列入《关于持久性有机污染物的斯德哥尔摩公约》附录B中[2],严格限制使用。我国在2013年8月批准了《关于持久性有机污染物的斯德哥尔摩公约》新增列9种持久性有机污染物的《关于附件A、附件B和附件C修正案》对PFOS及其盐类和全氟辛基磺酰氟做出限制规定。随着PFOS的禁用,氯代多氟烷基醚磺酸盐(chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonates, Cl-PFESA)作为替代物在2009年的使用量达到20~30 t[3],Cl-PFESA商品名为F-53B,在1970年开始广泛应用于中国电镀行业,2013年约有58%的镀铬厂使用Cl-PFESA抑制剂[4]。目前中国是唯一具有Cl-PFESA使用记录的国家,但缺乏对于Cl-PFESA的减量化和排放要求。2013年才首次报道了其环境浓度、持久性和毒性效应[5]。Cl-PFESA的环境持久性与PFOS相似,环境中的总停留时间估计为1 038 d[6]。最近的一项研究发现了Cl-PFESA的生物积累因子(bioaccumulation factors, BAFs)范围4.124~4.322高于PFOS(3.430~3.279)[7]。近年关于Cl-PFESA的环境影响已经引起关注,根据Web of Science的研究数据,采用VOSviewer软件进行了以“Cl-PFESA”和“F-53B”为关键字的可视化分析如图1所示。目前的研究主要集中于环境介质中的检测、动物体和人体的暴露水平、对生物体的毒性效应,已有的综述主要关注于Cl-PFESA的对人体和生物体的毒性研究,对于其在环境中的检出和分布情况、对环境影响、去除研究等还未有系统的综述。因此本文根据相关文献报道,总结了Cl-PFESA目前在环境中的检出状况、动物和人体的暴露水平、对生物体潜在的毒性影响和去除研究进展,以期为进一步研究Cl-PFESA的环境行为,评估其生态风险提供一定参考依据。

图1 关于关键词“Cl-PFESA”和“F-53B”的共现网络分析图

注:圆圈大小表示关键词出现次数,颜色变化表示不同时间阶段的研究关注点。

Fig. 1 Co-occurrence network analysis of the keyword “Cl-PFESA” and “F-53B”

Note: The size of the circle indicates the number of times the keyword appears, the color change indicates the research focus at different time periods.

1 Cl-PFESA概述(Overview of Cl-PFESA)

Cl-PFESA是作为灭铬雾剂被生产,在PFOS的碳链结构中引入醚键官能团,并用氯原子取代一个氟原子,可以降低成本和避免有毒化学品的使用[8]。Cl-PFESA依旧保持多氟化结构以及与PFOS相似的物理、化学特性,其log Kow值为7.07,具有较高的疏水性,C—F是最强的化学键,因此Cl-PFESA具有较高的稳定性,高度耐氧化性能、耐酸耐碱、低溶解度,商业产品中主要形式是6:2 Cl-PFESA,作为杂质产生的还有8:2 Cl-PFESA[9]。Cl-PFESA分子式和化学结构式如表1所示。

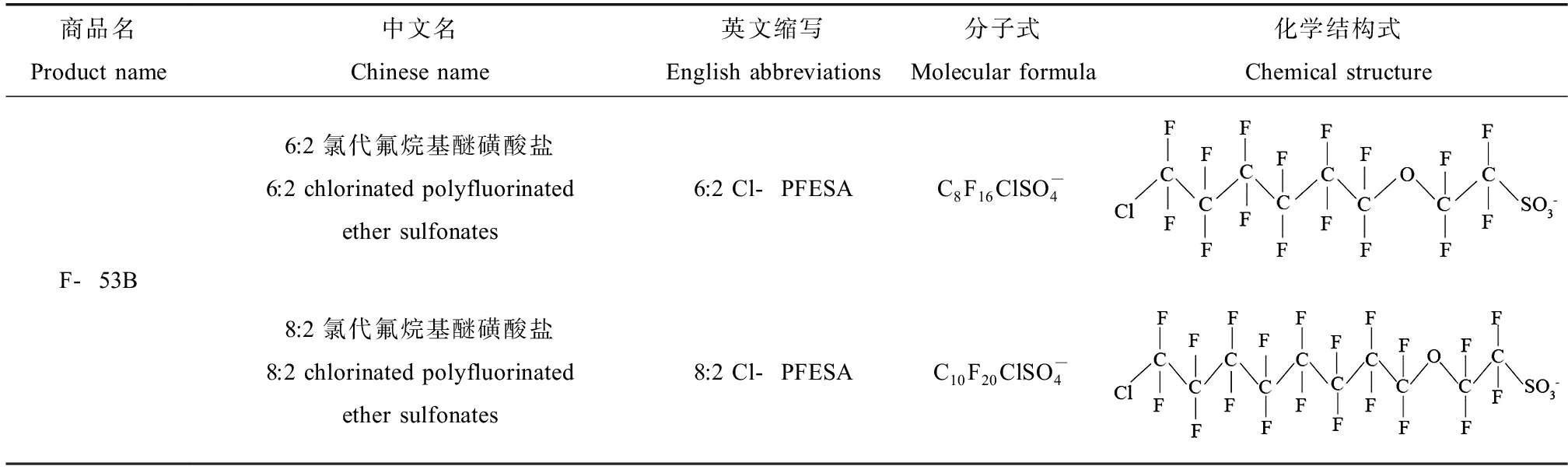

表1 Cl-PFESA分子式、CAS号及化学结构式

Table 1 Molecular formula, CAS number and chemical structure of Cl-PFESA

商品名Product name中文名Chinese name英文缩写English abbreviations分子式Molecular formula化学结构式Chemical structureF-53B6:2 氯代氟烷基醚磺酸盐6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonates6:2 Cl-PFESAC8F16ClSO-48:2 氯代氟烷基醚磺酸盐8:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonates8:2 Cl-PFESAC10F20ClSO-4

2 不同环境介质中Cl-PFESA的赋存情况(Occurrence of Cl-PFESA in different environmental media)

2.1 工业废水和市政污泥

Cl-PFESA商业品作为烟雾抑制剂使用,可避免工人在电解过程中接触到空气中的Cr(Ⅵ)喷雾以起到保护作用,广泛应用于金属电镀行业,因此氟化工厂及相关电镀工业废水的排放是环境中Cl-PFESA的重要来源[10]。据报道,某电镀工业废水中6:2 Cl-PFESA和8:2 Cl-PFESA含量分别为18%和0.7%,经污水处理工艺后收集的污泥样品中6:2 Cl-PFESA浓度达到22 000 ng·g-1,8:2 Cl-PFESA浓度3 200 ng·g-1[11]。在温州一个电镀工业的废水处理厂的进、出水口及受纳地表水中6:2 Cl-PFESA检测浓度达到μg·L-1水平[5]。城市污水处理厂是各种全氟化合物的主要汇集地,也成为环境中污染物的重要次级点源。Ruan等[12]在中国20个省市共56个污水处理厂脱水过程的新鲜消化污泥中均检测到6:2 Cl-PFESA(0.02~209 ng·g-1,以干质量计)和8:2 Cl-PFESA(0~31.8 ng·g-1,以干质量计)。在辽宁省一造纸厂废水排污口也检测到相关浓度282 ng·L-1,此外在未经处理的市政废水排放口中Cl-PFESA浓度则达到了7 600 ng·L-1[13]。表明无论是工业废水或是市政污水处理厂均不能有效降解Cl-PFESA,相关的工业废水、污水排放以及污泥的综合使用不可避免地将残留Cl-PFESA排放入自然水体和土壤环境中,工业废水和市政污水是环境中Cl-PFESA的一个重要排放源。

2.2 地表水和地下水

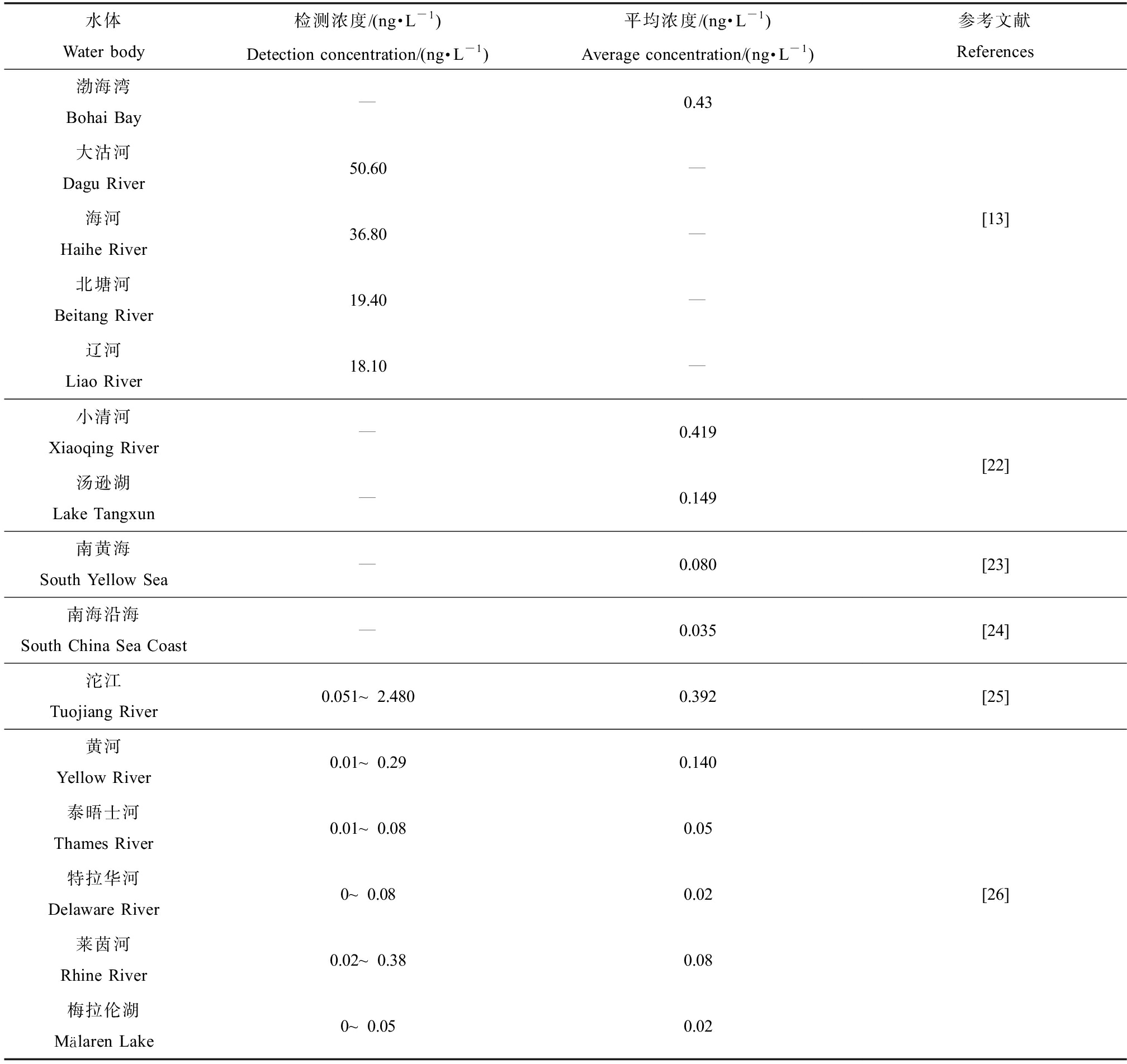

表2列出了中国和其他国家部分河流中Cl-PFESA检出浓度。由于Cl-PFESA在中国被广泛使用,在中国水环境中的检出浓度高于其他国家,水生环境中的浓度与PFOS相当[14-15],且已成为中国水域中发现的主要PFASs之一[16]。中国排放量较大的地区主要集中在华南、华东地区,中部和西部地区排放量较低,与中国镀铬企业的位置分布相关[4]。在中国河流中检测到Cl-PFESA,浓度范围最高达78.5 ng·L-1,主要以6:2 Cl-PFAES为主,总体范围为0.01~77 ng·L-1 [17]。东部沿海河口处检出频率51%,浓度范围0.56~78.5 ng·L-1,北方烟台沿海水域浓度范围为2.86~44.4 ng·L-1[18]。并且中国大陆湿降水中也检测到平均浓度为0.23 ng·L-1的6:2 Cl-PFESA[19]。Wei等[20]发现江苏非工业地区地下水受到一定Cl-PFESA污染,6:2 Cl-PFESA检测浓度0.17~1.83 ng·L-1,检测浓度低于地表水,可能是Cl-PFESA的疏水性使其更容易滞留在土壤介质中,向下迁移和淋溶作用的浓度较低。值得关注的是,南极州东部一些融冰湖中同样检测到6:2 Cl-PFESA,在除了部分地区的人类活动局部排放的PFASs,可能来自相关产品的释放,更多的主要来自空气传播[21]。因此大气沉降对非工业地区地下水中Cl-PFESA污染有重要影响。由于不同国家对于传统长链PFASs的使用替代物类型不同,Cl-PFESA目前在中国环境中的检出率较高,特别是中国南部、中部沿海地区以及北方沿海地区,已成为水环境中的主要全氟污染物。在非工业地区地下水中也发现一定Cl-PFESA的污染,因此了解Cl-PFESA在环境介质中的迁移规律,对系统掌握Cl-PFESA对环境的影响有较大意义。

表2 水体中Cl-PFESA的检测浓度

Table 2 Detection concentration of Cl-PFESA in water

水体Water body检测浓度/(ng·L-1)Detection concentration/(ng·L-1)平均浓度/(ng·L-1)Average concentration/(ng·L-1)参考文献References渤海湾Bohai Bay—0.43大沽河Dagu River50.60 —海河Haihe River36.80 —北塘河Beitang River19.40—辽河Liao River18.10—[13]小清河Xiaoqing River —0.419 汤逊湖Lake Tangxun—0.149[22]南黄海South Yellow Sea—0.080 [23]南海沿海South China Sea Coast—0.035[24]沱江Tuojiang River0.051~2.4800.392[25]黄河Yellow River0.01~0.290.140 泰晤士河Thames River0.01~0.080.05特拉华河 Delaware River0~0.080.02莱茵河Rhine River0.02~0.380.08 梅拉伦湖Mälaren Lake0~0.050.02 [26]

注:—为无可用数据。

Note: — no data available.

2.3 土壤与大气

Cl-PFESA在相关工业产品的生产制作以及使用过程,可通过粉末灰尘等途径进入到空气环境中,经大气介质进行远距离迁移,最终经过干湿沉降进入地表环境。在中国北方农田基质中发现6:2 Cl-PFESA的检出频率(98%)高于PFOS(83%)[27]。在我国31个省住宅区土壤中Cl-PFESA具有98.9%检测率,其中6:2 Cl-PFESA的浓度(0.16±0.20) ng·g-1、8:2 Cl-PFESA浓度(0.61±0.19) ng·g-1[28]。Cl-PFESA具有较强的疏水性,土壤的吸附作用对Cl-PFESA在地下的运输过程有较大影响,除了疏水作用、静电吸附,Cl-PFESA还可能通过配体交换取代羟基来与土壤矿物表面的金属氧化物相互作用,而土壤中Cu(Ⅱ)、Cr(Ⅵ)和硫酸盐对氧化物上吸附位点的竞争性占领,导致Cl-PFESA的吸附能力降低,因此一定浓度的Cu(Ⅱ)、Cr(Ⅵ)和硫酸盐可以促进Cl-PFESA在土壤环境中的迁移[29]。据报道,大连市大气颗粒物中检测到6:2 Cl-PFESA浓度呈上升趋势,在2014年浓度达到722 pg·m-3[30]。在河北石家庄室内灰尘中6:2 Cl-PFESA平均浓度3.28 ng·g-1,次于全氟丁酸(perfluorobutanoic acid, PFBA)和全氟辛酸(perfluorooctanoic acid, PFOA) [31],广州室内灰尘中检测到浓度为1.1 ng·g-1[32]。Zhang等[33]采集的广州市一工业园区和某高校学生宿舍、清远市某电子垃圾拆卸区3个区域灰尘,均检测到一定浓度的6:2 Cl-PFESA(平均检测浓度5.24、7.41和4.28 ng·g-1)、8:2 Cl-PFESA(平均检测浓度2.88、1.24和1.72 ng·g-1)。大气颗粒的沉降和含Cl-PFESA产品的直接释放是土壤环境中Cl-PFESA的重要来源,土壤的吸附作用会影响Cl-PFESA在地下环境的迁移,而土壤对Cl-PFESA的富集能力与土壤的理化性质、有机质含量有关,因此有必要关注Cl-PFESA在土壤中行为机制。此外,大气中Cl-PFESA的污染增加了人体呼吸暴露的危险,因此对于大气中Cl-PFESA的检测和防治十分重要。

3 生物、人体暴露水平及毒性评估(Biological, human exposure level and toxicity assessment)

3.1 生物暴露水平及毒性

3.1.1 生物体暴露水平

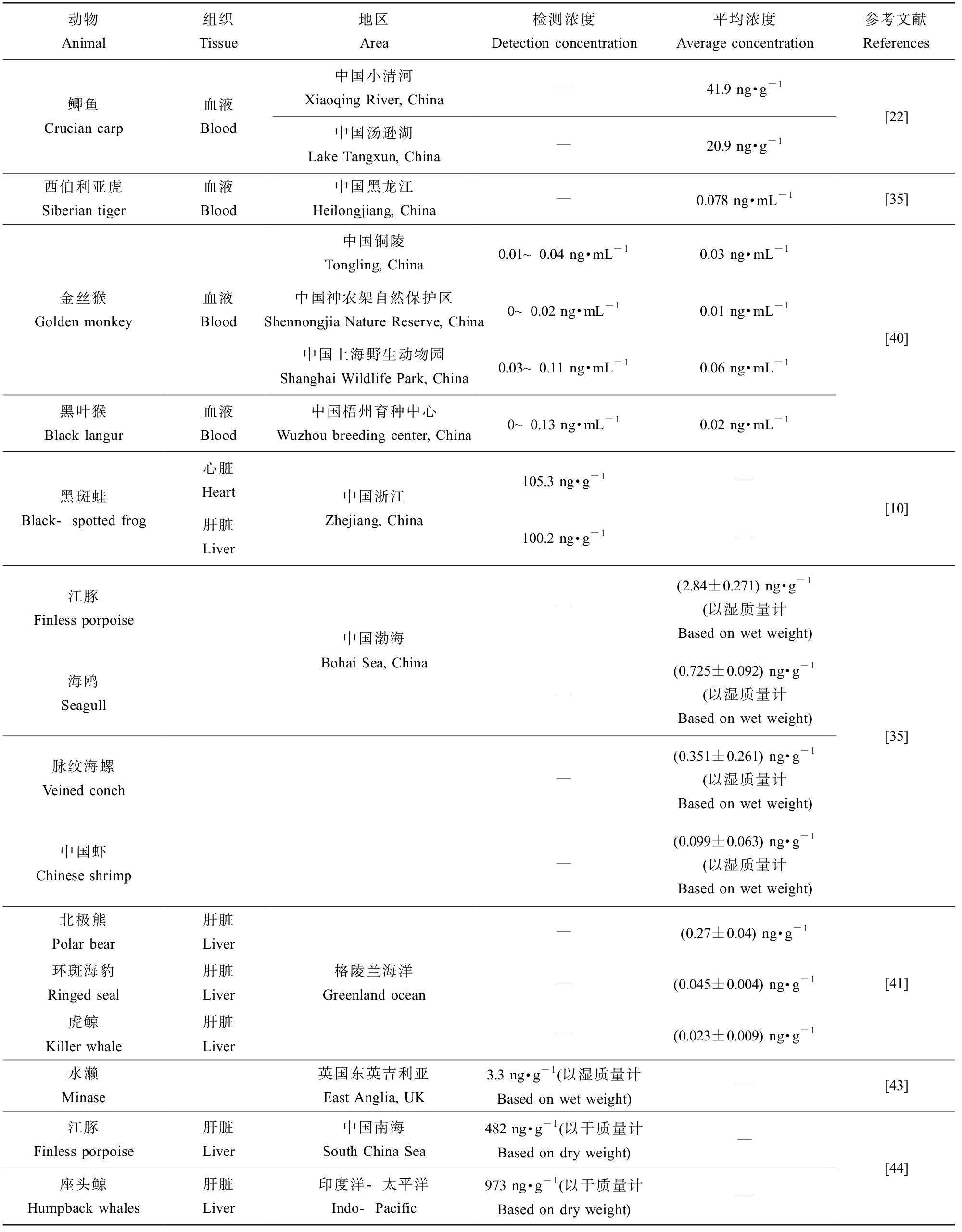

据报道Cl-PFESA在中国渤海海洋生物中广泛存在,浓度和检出频率也呈逐年上升趋势[34]。渤海生物体中6:2 Cl-PFESA和8:2 Cl-PFESA的检出频率分别为81.3%和2.67%,6:2 Cl-PFESA在海洋生物中的检出频率甚至高于PFOS(77.33%),也有迹象表明Cl-PFESA可以在水生食物网中被生物放大[35]。6:2 Cl-PFESA在野生鲫鱼中log BAFs范围为4.1~4.3 [21],淡水藻中log BAFs为4.66±0.06[36],在黑斑蛙中发现6:2 Cl-PFESA的BAFs高于PFOS,且很容易在鱼组织中积累,消除缓慢[37-38]。有研究表明环境中聚苯乙烯微塑料的吸附作用可减少Cl-PFESA生物积累,但会诱导斑马鱼幼虫的炎症应激[39]。Cui等[40]首次报道的灵长类动物上海野生动物园的金丝猴体内6:2 Cl-PFESA浓度会随着年龄的增长而显著增加,可能是6:2 Cl-PFESA具有较大的生物持久性,同时环境介质中Cl-PFESA的暴露和日常饮食的摄入导致6:2 Cl-PFESA浓度在体内不断积累。在格陵兰东部的北极野生动物、海洋哺乳动物中检测到生物积累,首次证实了其长期远程极地环境的范围传输潜力[41]。表3列出了6:2 Cl-PFESA在动物组织中检测浓度。在不同生物体内积累差距可能归因于污染物暴露水平,生物的营养水平等,营养水平较高的生物体内Cl-PFESA检测出浓度高[42]。这些结果表明Cl-PFESA的生物积累性与PFOS相当甚至更高,在生物体的生物量积累特征值得持续关注。

表3 动物体内6∶2 Cl-PFESA检测浓度

Table 3 Detection concentration of 6:2 Cl-PFESA in animals

动物Animal组织Tissue地区Area检测浓度Detection concentration 平均浓度Average concentration参考文献References鲫鱼Crucian carp血液Blood中国小清河Xiaoqing River, China—41.9 ng·g-1中国汤逊湖Lake Tangxun, China—20.9 ng·g-1[22]西伯利亚虎Siberian tiger血液Blood中国黑龙江Heilongjiang, China—0.078 ng·mL-1[35]金丝猴Golden monkey血液Blood黑叶猴Black langur血液Blood中国铜陵Tongling, China0.01~0.04 ng·mL-10.03 ng·mL-1中国神农架自然保护区Shennongjia Nature Reserve, China0~0.02 ng·mL-10.01 ng·mL-1中国上海野生动物园Shanghai Wildlife Park, China0.03~0.11 ng·mL-10.06 ng·mL-1中国梧州育种中心Wuzhou breeding center, China0~0.13 ng·mL-10.02 ng·mL-1[40]黑斑蛙Black-spotted frog心脏Heart肝脏Liver中国浙江Zhejiang, China105.3 ng·g-1—100.2 ng·g-1—[10] 江豚Finless porpoise海鸥Seagull脉纹海螺Veined conch中国虾Chinese shrimp中国渤海Bohai Sea, China —(2.84±0.271) ng·g-1(以湿质量计Based on wet weight)—(0.725±0.092) ng·g-1(以湿质量计Based on wet weight)—(0.351±0.261) ng·g-1(以湿质量计Based on wet weight)—(0.099±0.063) ng·g-1(以湿质量计Based on wet weight)[35] 北极熊Polar bear肝脏Liver环斑海豹Ringed seal肝脏Liver虎鲸Killer whale肝脏Liver格陵兰海洋Greenland ocean—(0.27±0.04) ng·g-1—(0.045±0.004) ng·g-1—(0.023±0.009) ng·g-1[41]水濑Minase英国东英吉利亚East Anglia, UK3.3 ng·g-1 (以湿质量计Based on wet weight)—[43] 江豚Finless porpoise肝脏Liver中国南海South China Sea482 ng·g-1 (以干质量计Based on dry weight)—座头鲸Humpback whales肝脏Liver印度洋-太平洋Indo-Pacific973 ng·g-1 (以干质量计Based on dry weight)—[44]

注:—为无可用数据。

Note: — no data available.

3.1.2 Cl-PFESA的生物健康效应

Cl-PFESA具有较高的生物毒性,认为Cl-PFESA的存在潜在健康风险。鱼类作为水生环境中的一类脊椎动物已被广泛作毒理学研究的模型。Cl-PFESA在斑马鱼胚胎中表现出了高于PFOS的生物浓缩潜力和最强的代谢干扰作用[45]。Wang等[5]发现Cl-PFESA和PFOS二者对斑马鱼致死浓度分别为15.5 ng·L-1和17.0 ng·L-1。将斑马鱼胚胎持续暴露3 mg·L-1浓度时,Cl-PFESA在斑马鱼胚胎中高度积累,出现了孵化延迟、畸形发生率增加和存活率降低,产生心血管系统毒性[46]。斑马鱼胚胎在暴露于200 μg·L-1浓度后,抗氧化基因的活性水平、mRNA和蛋白质水平均出现不同程度的下降,触发斑马鱼幼虫的氧化应激[47]。Cl-PFESA能够与斑马鱼甲状腺素运载蛋白结合,从而干扰甲状腺激素稳态[48]。一定浓度的Cl-PFESA可以使斑马鱼甲状腺素水平升高,破坏甲状腺内分泌系统[49],并且还具有跨代甲状腺干扰能力[50],对中国珍稀鲦鱼也具有相似的甲状腺破坏和跨代影响作用[51]。一定浓度Cl-PFESA暴露导致SD小鼠甲状腺激素的血清浓度降低,还诱导滤泡增生,破坏甲状腺功能[52]。Pan等[53]指出一定浓度的6:2 Cl-PFESA可诱导雌性小鼠损伤和功能障碍。Zhang等[48]研究了6:2 Cl-PFESA对成年小鼠的亚慢性肝毒性,暴露于剂量高于0.2 mg·kg-1·d-1时相对肝脏质量增加,同时观察到肝脏细胞凋亡和增殖,表现出比PFOS更严重的肝毒性。将雌、雄性小鼠暴露于10 mg·L-1的Cl-PFESA,10周后Cl-PFESA在结肠、回肠和血清中显著积累,并导致雌性和雄性小鼠的肠道屏障功能障碍和结肠炎症[54]。以上结果表明,Cl-PFESA毒性作用与PFOS相当,甚至更高,在动物体中不断积累会产生胚胎和肝脏发育毒性、破坏甲状腺分泌系统和肠道功能。

3.1.3 Cl-PFESA的生态毒性

Cl-PFESA浓度达到mg级时,可干扰藻类叶绿素含量和细胞膜通透性,引起线粒体功能异常,对藻类的生长产生不良影响[35]。Pan等[55]报道了6:2 Cl-PFAES可刺激绿豆根部产生过量的羟基自由基从而抑制绿豆的发育,对绿豆的植物毒性高于PFOS可能是6:2 Cl-PFAES对载体蛋白具有更高的亲和力。研究表明Cl-PFAES对藻类和植物的生长也产生抑制作用,当前环境中的污染浓度暂未对植物产生明显的毒性作用,但在植物中Cl-PFAES的富集有助于其在各食物链中放大。

3.2 人体暴露水平及毒性

3.2.1 人体暴露水平

人体中Cl-PFESA的可通过呼吸、皮肤接触、饮用水和日常饮食摄入等途径积累,Cl-PFESA在中国人体样本的生物监测中也具有较高的出现率。在电镀厂工人以及高食用鱼类产品人群的血清中Cl-PFESA浓度为51.5 ng·L-1和93.7 ng·L-1,明显高于普通地区(4.78 ng·L-1)[56]。有报道北京采集居民日常食用鱼类和肉质品中均含有一定浓度6:2 Cl-PFESA,并且在鱼类样本中6:2 Cl-PFESA的浓度水平远高于PFOA[57]。中国中部和东部地区普通居民血清中检测到6:2 Cl-PFESA中值浓度2.18 ng·mL-1,是第三高贡献的PFASs,积累浓度与年龄呈正相关性[58]。在山东省某氟化工厂附近2所学校学生血液中检测到6:2 Cl-PFESA均值浓度分别为1.26 ng·mL-1和1.14 ng·mL-1[59],6:2 Cl-PFESA与人类血清蛋白的结合亲和力高于PFOS具有更高的生物积累潜力[60]。研究表明6:2 Cl-PFESA已成为中国母体和脐带血清中第三大流行的PFASs。广州地区母亲血清中PFASs以PFOS(7.15 ng·mL-1)为主,其次为6:2 Cl-PFESA(2.41 ng·mL-1)[61]。天津地区孕妇血清中6:2 Cl-PFESA的暴露水平高于PFOS,平均浓度为6.436 ng·mL-1[62]。Cl-PFESA在人类母乳中同样被广泛检测出,杭州女性母乳中6:2 Cl-PFESA含量0.028 ng·mL-1,远低于血液中浓度[63]。但Cl-PFESA可能比传统的PFAS更容易穿过胎盘,而8:2 Cl-PFESA在胎盘上的运输程度高于6:2 Cl-PFESA,可能是因为它具有较高的疏水性和较低的血浆蛋白结合亲和力[64]。母体体内积累的Cl-PFESA可以通过脐带和胎盘以及母乳喂养等途径转移至新生儿体内[65]。一项调查显示,在武汉新生儿样本中6:2 Cl-PFESA和8:2 Cl-PFESA的检出频率分别为100%和96%[66]。在人体中血液已广泛检测出Cl-PFESA,其检出浓度与生活环境和饮食习惯相关。母乳中也检测出一定浓度的Cl-PFESA,并发现Cl-PFESA可以通过脐带、胎盘和母乳等途径导致新生儿暴露的风险,因此Cl-PFESA在人体中的累积途径和规律,以及对新生儿健康的影响值得关注。

3.2.2 Cl-PFESA对人体潜在影响

Yang等[67]采用基于人类胚胎干细胞的心脏分化系统和全转录组学分析来评估Cl-PFESA和PFOS的潜在心脏发育毒性,发现Cl-PFESA抑制心脏分化并促进心外膜迁移的效果比PFOS更强,是因为Cl-PFESA暴露破坏了更多基因的表达并降低心脏分化效率。6:2 Cl-PFESA可诱导人肝HL-7 702细胞系的细胞增殖,对细胞活力的毒性作用比PFOS更大,并且对人肝脂肪酸结合具有独特的结合模式与更高的结合能力[68]。人体暴露于低剂量的6:2 Cl-PFAES后,可促进细胞脂质的积累,还可能加重肝脏代谢紊乱[69]。可见Cl-PFAES会对人体心脏、肝脏和细胞代谢产生影响,但对人体是否有其他危害还缺少调查,Cl-PFAES的毒性评估值得关注。

4 对Cl-PFESA的去除研究(Study on removal of Cl-PFESA)

自然环境Cl-PFESA的降解过程主要发生在水体,表层海洋,少部分会被沉积物掩埋和迁移至海洋[4],而6:2 Cl-PFESA和8:2 Cl-PFESA在土壤中的好氧生物降解可忽略不计[19]。现阶段工业废水对于Cl-PFESA处理多采用污泥沉淀法,但不同的处理单元对Cl-PFESA的处理效果影响较大,会出现Cl-PFESA的溶解态浓度富集,某电镀废水处理工艺出水中6:2 Cl-PFESA平均浓度是进水浓度220 ng·L-1的3.36倍[11]。有关Cl-PFESA降解方法主要有吸附法、还原法、机械化学法和电化学法。

4.1 吸附法

吸附法是常用且经济的方法,层状双金属氢氧化物材料(layered double hydroxide, LDH)对Cl-PFESA的吸附去除研究中,发现因为离子交换是主要机制,附加机制为O—H/O/F和C—F/Cl/H氢键,十二烷基硫酸钠(sodium dodecyl sulfate, SDS)具有更高的比表面积,较高的比表面积和SDS的存在可以分别产生更多的O—H/O/F和C—F/Cl/H氢键位点,进而增强SDS-LDH对Cl-PFESA的吸收。![]() 和SDS-LDH都能够从水体中快速去除Cl-PFESA,且SDS-LDH具有更高的去除效果[70]。有研究发现阴离子交换树脂IRA67对Cl-PFESA的吸附容量为4.2 mmol·g-1,低pH条件下吸附效果较高,存在静电相互作用、疏水作用和胶束和半胶束形成等作用机制[71]。吸附法适用广泛,对污染物的去除具有较好的效果,吸附法仅从水环境中将污染物去除,但并未改变污染物的化学性质,无法使其矿化降解。

和SDS-LDH都能够从水体中快速去除Cl-PFESA,且SDS-LDH具有更高的去除效果[70]。有研究发现阴离子交换树脂IRA67对Cl-PFESA的吸附容量为4.2 mmol·g-1,低pH条件下吸附效果较高,存在静电相互作用、疏水作用和胶束和半胶束形成等作用机制[71]。吸附法适用广泛,对污染物的去除具有较好的效果,吸附法仅从水环境中将污染物去除,但并未改变污染物的化学性质,无法使其矿化降解。

4.2 还原法

氰钴铵素(VB12)在催化还原降解卤代有机污染中具有广泛应用[72],可作为电子载体有效提高卤代有机污染物的降解速率和还原脱卤效果[73-74]。研究表明6:2 Cl-PFESA对还原脱卤同样具有敏感性,在添加外源VB12的厌氧超还原试验中观察到定量的6:2 Cl-PFESA发生快速转变,氢取代的多氟烷基醚磺酸盐(1H-6:2 PFESA)确定为主要产物[75]。厌氧废水污泥、厌氧消化器中微生物和厌氧脱氯微生物可以不同程度下实现6:2 Cl-PFESA完全脱氯,但未观察到还原性脱氟,6:2 H-PFESA鉴定为唯一的代谢产物[76]。金属电镀设施附近2个不同区域的河水和沉积物样品中发现了氢取代的1H-6:2 PFESA和1H-8:2 PFESA,推测可能是生物降解产物。6:2 Cl-PFESA在动物体由还原酶介导的生物转化产物为6:2 H-PFESA[77]。因此氢取代的多氟烷基醚磺酸盐可能是Cl-PFESA降解的一条途径。

高级还原法产生水合电子![]() 具有较高的还原点位

具有较高的还原点位![]() 可实现卤化有机污染物还原脱卤。氟原子的强电负性使其具有较强的电子亲和力,

可实现卤化有机污染物还原脱卤。氟原子的强电负性使其具有较强的电子亲和力,![]() 会优先攻氟原子实现还原脱氟,应用于PFASs的降解也是一种有效途径。Cao等[78]采用紫外光催化碘化钾产生的大量

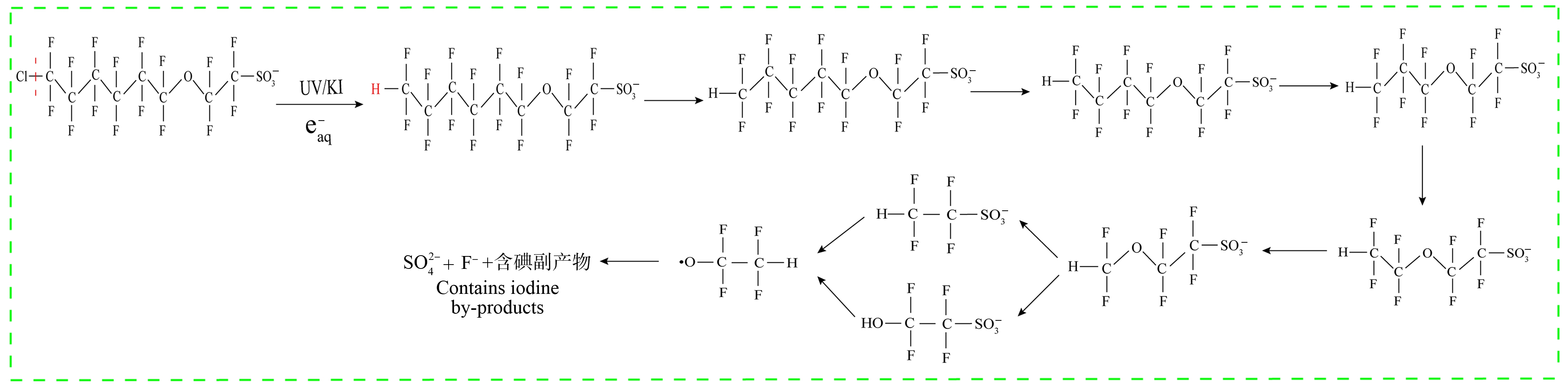

会优先攻氟原子实现还原脱氟,应用于PFASs的降解也是一种有效途径。Cao等[78]采用紫外光催化碘化钾产生的大量![]() 降解水溶液中Cl-PFESA,加入0.3 mmol碘化钾,在反应45 min内Cl-PFESA降解率超过95%。降解过程首先是脱氯,随后以醚键左侧的CF2基团为单元不断剥离,最后形成

降解水溶液中Cl-PFESA,加入0.3 mmol碘化钾,在反应45 min内Cl-PFESA降解率超过95%。降解过程首先是脱氯,随后以醚键左侧的CF2基团为单元不断剥离,最后形成![]() 或

或![]() 体系对Cl-PFESA具有较高的降解效果,但Cl-PFESA并没有被完全矿化,依旧存在中间产物和残留物,推测降解路径如图2所示。

体系对Cl-PFESA具有较高的降解效果,但Cl-PFESA并没有被完全矿化,依旧存在中间产物和残留物,推测降解路径如图2所示。![]() 主导的还原降解对水体中的PFASs表现出有效的化学破坏,但降解过程会产生惰性的盐残留物(碘化物和硫酸盐),会增加出水中的总溶解固体含量,以及含氟副产物的鉴定和毒性需要考虑,并且水体中pH和溶解氧含量对还原降解效果具有较大的影响,要控制pH和溶解氧浓度会较大的增加处理成本[79]。

主导的还原降解对水体中的PFASs表现出有效的化学破坏,但降解过程会产生惰性的盐残留物(碘化物和硫酸盐),会增加出水中的总溶解固体含量,以及含氟副产物的鉴定和毒性需要考虑,并且水体中pH和溶解氧含量对还原降解效果具有较大的影响,要控制pH和溶解氧浓度会较大的增加处理成本[79]。

图2 UV/KI降解Cl-PFESA路径图[78]

Fig. 2 UV/KI degradation pathway of Cl-PFESA[78]

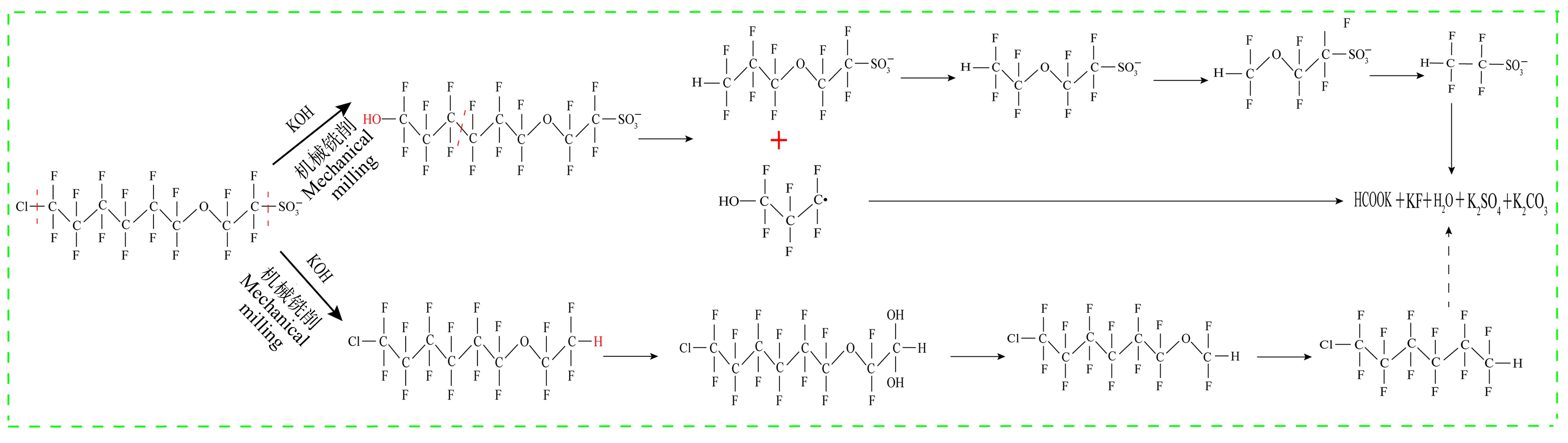

4.3 机械化学法

机械化学法通过机械力改变固体反应物的物理化学性质,可增强其反应活性,具有高效环保降解有机污染物的优势[80]。Yan等[81]采用机械化学法,使用过硫酸钠(sodium persulfate, PS)为研磨剂,加入碱活化剂时,在比例为PS∶NaOH∶Cl-PFESA=4.17∶1.75∶0.05研磨8 h后,88%的Cl-PFESA被破坏且实现较大矿化,氟化物回收率为54%,破坏效率也与研磨时间密切相关。通过球磨装置用氢氧化钾(KOH)研磨,Cl-PFESA被迅速破坏并高度矿化,有机C—F键断裂,生成甲酸盐和无机氟化物,最终产品为氟化钾(KF)、氯化钾(KCl)、过硫酸钾(K2S2O8)和甲酸钾(HCOOK),降解路径如图3所示[82]。表明机械化学处理是一种有前途的Cl-PFESA处理方法,可消除其持久性、生物累积性和毒性,但机械化学法仅适用于降解固体污染物,对于水环境中Cl-PFESA的去除存在局限性。

图3 机械化学法降解Cl-PFESA路径图[82]

Fig. 3 Mechanochemical degradation of Cl-PFESA pathway[82]

4.4 电化学法

Zhuo等[83]研究改性硼掺杂金刚石(boron-doped diamond, BDD)的4种阳极:BDD、BDD/SnO2、BDD/PbO2和BDD/SnO2-F对Cl-PFESA的电化学氧化降解中,BDD/PbO2阳极在前10 min内对Cl-PFESA去除率保持在较高水平,而BDD/SnO2-F具有更高的电催化能力,主要是阳极的析氧电位最高,F的引入增加了氧化锡(SnO2)的电导率,且F的电负性较强,增加了阳极上的活性位点,使得更多的Cl-PFESA能够吸附在阳极上直接发生电化学氧化,最大去除率达到95.6%。降解产物及其路径如图2~4所示。室内实验研究中,电化学法对污染物表现出较高的去除和矿化效果,今后方向应考虑对更优的阴/阳极材料的选择、对实际应用的适用性和经济问题。

图4 电化学法降解Cl-PFESA路径图[83]

Fig. 4 Electrochemical degradation of Cl-PFESA pathway[83]

5 展望(Future)

(1) Cl-PFESA目前在中国环境中的检出率较高,水环境、沉积物、土壤、空气、动物甚至人体中被检测出,较高浓度检出主要集中在地表水以及沿海水域,已成为水环境甚至动物体中的主要全氟污染物,其在水体和动物体的含量分别在ng·L-1和ng·mL-1水平,其浓度仍不断积累和增加。但Cl-PFESA在土壤和地下水中的污染数据缺乏,且在各介质中的迁移规律和环境归趋还未明确,因此系统探究Cl-PFESA在环境的排放分布、迁移和转化规律对于评估其环境污染具有很大意义。

(2) 研究表明Cl-PFESA表现出比PFOS更严重的生物毒性,对水生鱼类具有肝毒性,影响胚胎发育,诱导性雌激素紊乱、甲状腺激素分泌紊乱并具有跨代干扰作用。对哺乳动物小鼠产生肝脏毒性、破坏甲状腺系统和肠道功能,对藻类和植物生长产生抑制作用。Cl-PFESA在各环境介质中的污染浓度可能对动植物并未直接产生毒性作用,但在动植物体中的生物持久性和高积累性可以使其在各食物链中进行生物放大,累积到mg·L-1水平时对动植物产生明显的毒性甚至致死作用。Cl-PFESA在人体血液以及母乳中的检测含量达ng·mL-1级别,可以通过胎盘、脐带和母乳传递而导致新生儿暴露的危险,目前的研究表明Cl-PFESA对人类健康存在潜在危害,但相关数据还不足以对Cl-PFESA进行系统的毒性评估,应对Cl-PFESA在人体和动物各组织的分布、毒性作用机理和消除规律等进一步研究,以完善对Cl-PFESA的风险评估。

(3) Cl-PFESA同样表现出难降解性、脱氟率低。污水处理工艺不能稳定有效降解Cl-PFESA,由于其自身特殊化学结构使其对常规高级氧化降解具有一定抗性,而电化学氧化对Cl-PFESA去除效果较好,但降解产物的鉴定、更多新材料和较优条件的选择还需更多的研究,对于实际大规模的应用也需考虑。VB12等金属辅酶作为电子载体参与还原降解以及高级还原法对卤代有机污染物具有较好的还原脱卤效果,用于Cl-PFESA的还原降解也可能是一种有效的降解方法,降解效果及其还原降解机制的进一步研究有利于环境Cl-PFESA污染修复。机械化学法可实现固态Cl-PFESA的去除和矿化,但对于水环境中Cl-PFESA的去除具有局限性,吸附法目前是快速有效的水环境修复方法,但并没有改变污染物的化学性质,进行后续的处理也可能引起二次污染,采用吸附法协同机械化学法对水环境中Cl-PFESA是否可以实现有效降解且不产生二次污染还有待研究。目前对于Cl-PFESA降解研究仍处于室内实验室研究,对Cl-PFESA的更多高效经济的降解方法、产物鉴定及机理的相关探究,可能是未来对环境中Cl-PFESA污染修复的方向。

[1] 朱永乐, 汤家喜, 李梦雪, 等. 全氟化合物污染现状及与有机污染物联合毒性研究进展[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2021, 16(2): 86-99

Zhu Y L, Tang J X, Li M X, et al. Contamination status of perfluorinated compounds and its combined effects with organic pollutants [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2021, 16(2): 86-99 (in Chinese)

[2] United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The New POPs under the Stockholm Convention [EB/OL]. [2022-07-08]. http://chm. pops. int/TheConvention/The POPs/The New POPs/tabid/2511/Default. aspx

[3] Zhongke I. Electro fluorination and its fine-fluorine production branches [J]. Chemical Production and Technology, 2010, 17(4): 1-7

[4] Ti B W, Li L, Liu J G, et al. Global distribution potential and regional environmental risk of F-53B [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 640-641: 1365-1371

[5] Wang S W, Huang J, Yang Y, et al. First report of a Chinese PFOS alternative overlooked for 30 years: Its toxicity, persistence, and presence in the environment [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2013, 47(18): 10163-10170

[6] Gomis M I, Wang Z Y, Scheringer M, et al. A modeling assessment of the physicochemical properties and environmental fate of emerging and novel per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2015, 505: 981-991

[7] Huang Y, Chen Q Q, Deng M H, et al. Heavy metal pollution and health risk assessment of agricultural soils in a typical peri-urban area in southeast China [J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2018, 207: 159-168

[8] 盛南, 潘奕陶, 戴家银. 新型全氟及多氟烷基化合物生态毒理研究进展[J]. 安徽大学学报(自然科学版), 2018, 42(6): 3-13

Sheng N, Pan Y T, Dai J Y. Current research status of several emerging per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) [J]. Journal of Anhui University (Natural Science Edition), 2018, 42(6): 3-13 (in Chinese)

[9] 关景云. F-53B铬雾抑制剂的应用 [J]. 林业机械, 1988, 16(6): 57-59

[10] Wang Y, Chang W G, Wang L, et al. A review of sources, multimedia distribution and health risks of novel fluorinated alternatives [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019, 182: 109402

[11] Liu S Y, Jin B, Arp H P H, et al. The fate and transport of chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonates and other PFAS through industrial wastewater treatment facilities in China [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2022, 56(5): 3002-3010

[12] Ruan T, Lin Y F, Wang T, et al. Identification of novel polyfluorinated ether sulfonates as PFOS alternatives in municipal sewage sludge in China [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2015, 49(11): 6519-6527

[13] Chen H, Han J B, Zhang C, et al. Occurrence and seasonal variations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) including fluorinated alternatives in rivers, drain outlets and the receiving Bohai Sea of China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 231(Pt 2): 1223-1231

[14] Cai Y Z, Wang X H, Wu Y L, et al. Temporal trends and transport of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in a subtropical estuary: Jiulong River Estuary, Fujian, China [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 639: 263-270

[15] Bao Y X, Deng S S, Jiang X S, et al. Degradation of PFOA substitute: GenX (HFPO-DA ammonium salt): Oxidation with UV/persulfate or reduction with UV/sulfite? [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2018, 52(20): 11728-11734

[16] Lin Y F, Liu R Z, Hu F B, et al. Simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis of fluoroalkyl sulfonates in riverine water by liquid chromatography coupled with Orbitrap high resolution mass spectrometry [J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2016, 1435: 66-74

[17] Munoz G, Liu J X, Vo Duy S, et al. Analysis of F-53B, Gen-X, ADONA, and emerging fluoroalkylether substances in environmental and biomonitoring samples: A review [J]. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 2019, 23: e00066

[18] Wang T, Vestergren R, Herzke D, et al. Levels, isomer profiles, and estimated riverine mass discharges of perfluoroalkyl acids and fluorinated alternatives at the mouths of Chinese Rivers [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2016, 50(21): 11584-11592

[19] Chen H, Choi Y J, Lee L S. Sorption, aerobic biodegradation, and oxidation potential of PFOS alternatives chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acids [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2018, 52(17): 9827-9834

[20] Wei C L, Wang Q, Song X, et al. Distribution, source identification and health risk assessment of PFASs and two PFOS alternatives in groundwater from non-industrial areas [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2018, 152: 141-150

[21] Shan G Q, Xiang Q, Feng X M, et al. Occurrence and sources of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the ice-melting lakes of Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 781: 146747

[22] Shi Y L, Vestergren R, Zhou Z, et al. Tissue distribution and whole body burden of the chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acid F-53B in crucian carp (Carassius carassius): Evidence for a highly bioaccumulative contaminant of emerging concern [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2015, 49(24): 14156-14165

[23] Feng X M, Ye M Q, Li Y, et al. Potential sources and sediment-pore water partitioning behaviors of emerging per/polyfluoroalkyl substances in the South Yellow Sea [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 389: 122124

[24] Wang Q, Tsui M M P, Ruan Y F, et al. Occurrence and distribution of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in the seawater and sediment of the South China Sea coastal region [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 231: 468-477

[25] 宋娇娇, 汪艺梅, 孙静, 等. 沱江流域典型及新兴全氟/多氟化合物的污染特征及来源解析[J]. 环境科学, 2022, 43(9): 4522-4531

Song J J, Wang Y M, Sun J, et al. Pollution characteristics and source apportionment of typical and emerging per- and polyfluoroalkylated pubstances in Tuojiang River Basin [J]. Environmental Science, 2022, 43(9): 4522-4531 (in Chinese)

[26] Pan Y T, Zhang H X, Cui Q Q, et al. Worldwide distribution of novel perfluoroether carboxylic and sulfonic acids in surface water [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2018, 52(14): 7621-7629

[27] Lan Z H, Yao Y M, Xu J Y, et al. Novel and legacy per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in a farmland environment: Soil distribution and biomonitoring with plant leaves and locusts [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 263(Pt A): 114487

[28] Li J F, He J H, Niu Z G, et al. Legacy per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and alternatives (short-chain analogues, F-53B, GenX and FC-98) in residential soils of China: Present implications of replacing legacy PFASs [J]. Environment International, 2020, 135: 105419

[29] Wei C L, Song X, Wang Q, et al. Influence of coexisting Cr(Ⅵ) and sulfate anions and Cu(Ⅱ) on the sorption of F-53B to soils [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 216: 507-515

[30] Liu W, Qin H, Li J W, et al. Atmospheric chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate and ionic perfluoroalkyl acids in 2006 to 2014 in Dalian, China [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2017, 36(10): 2581-2586

[31] Wang Y, Li X T, Zheng Z, et al. Chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acids in fish, dust, drinking water and human serum: From external exposure to internal doses [J]. Environment International, 2021, 157: 106820

[32] Xu F P, Chen D, Liu X T, et al. Emerging and legacy per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in house dust from South China: Contamination status and human exposure assessment [J]. Environmental Research, 2021, 192: 110243

[33] Zhang B, He Y, Huang Y Y, et al. Novel and legacy poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in indoor dust from urban, industrial, and e-waste dismantling areas: The emergence of PFAS alternatives in China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 263: 114461

[34] Liu Y W, Ruan T, Lin Y F, et al. Chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acids in marine organisms from Bohai Sea, China: Occurrence, temporal variations, and trophic transfer behavior [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2017, 51(8): 4407-4414

[35] Chen H, Han J B, Cheng J Y, et al. Distribution, bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acids in the marine food web of Bohai, China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 241: 504-510

[36] Liu W, Li J W, Gao L C, et al. Bioaccumulation and effects of novel chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate in freshwater alga Scenedesmus obliquus [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 233: 8-15

[37] Cui Q Q, Pan Y T, Zhang H X, et al. Occurrence and tissue distribution of novel perfluoroether carboxylic and sulfonic acids and legacy per/polyfluoroalkyl substances in black-spotted frog (Pelophylax nigromaculatus) [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2018, 52(3): 982-990

[38] Wu Y M, Deng M, Jin Y X, et al. Toxicokinetics and toxic effects of a Chinese PFOS alternative F-53B in adult zebrafish [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019, 171: 460-466

[39] Yang H L, Lai H, Huang J, et al. Polystyrene microplastics decrease F-53B bioaccumulation but induce inflammatory stress in larval zebrafish [J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 255: 127040

[40] Cui Q Q, Shi F L, Pan Y T, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in the blood of two colobine monkey species from China: Occurrence and exposure pathways [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 674: 524-531

[41] Gebbink W A, Bossi R, Rigét F F, et al. Observation of emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in Greenland marine mammals [J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 144: 2384-2391

[42] Wang Y J, Yao J Z, Dai J Y, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in blood of captive Siberian tigers in China: Occurrence and associations with biochemical parameters [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 265(Pt B): 114805

[43] Androulakakis A, Alygizakis N, Gkotsis G, et al. Determination of 56 per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in top predators and their prey from Northern Europe by LC-MS/MS [J]. Chemosphere, 2022, 287(Pt 2): 131775

[44] Wang Q, Ruan Y F, Jin L J, et al. Target, nontarget, and suspect screening and temporal trends of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in marine mammals from the South China Sea [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2021, 55(2): 1045-1056

[45] Tu W Q, Martínez R, Navarro-Martin L, et al. Bioconcentration and metabolic effects of emerging PFOS alternatives in developing zebrafish [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2019, 53(22): 13427-13439

[46] Shi G H, Cui Q Q, Pan Y T, et al. 6:2 Chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate, a PFOS alternative, induces embryotoxicity and disrupts cardiac development in zebrafish embryos [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2017, 185: 67-75

[47] Wu Y M, Huang J, Deng M, et al. Acute exposure to environmentally relevant concentrations of Chinese PFOS alternative F-53B induces oxidative stress in early developing zebrafish [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 235: 945-951

[48] Zhang H X, Zhou X J, Sheng N, et al. Subchronic hepatotoxicity effects of 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate (6:2 Cl-PFESA), a novel perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) alternative, on adult male mice [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2018, 52(21): 12809-12818

[49] Deng M, Wu Y M, Xu C, et al. Multiple approaches to assess the effects of F-53B, a Chinese PFOS alternative, on thyroid endocrine disruption at environmentally relevant concentrations [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 624: 215-224

[50] Shi G H, Wang J X, Guo H, et al. Parental exposure to 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate (F-53B) induced transgenerational thyroid hormone disruption in zebrafish [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 665: 855-863

[51] Liu W, Yang J, Li J W, et al. Toxicokinetics and persistent thyroid hormone disrupting effects of chronic developmental exposure to chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate in Chinese rare minnow [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 263(Pt B): 114491

[52] Hong S H, Lee S H, Yang J Y, et al. Orally administered 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate (F-53B) causes thyroid dysfunction in rats [J]. Toxics, 2020, 8(3): 54

[53] Pan Z H, Miao W Y, Wang C Y, et al. 6:2 Cl-PFESA has the potential to cause liver damage and induce lipid metabolism disorders in female mice through the action of PPAR-γ [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 287: 117329

[54] Pan Z H, Yuan X L, Tu W Q, et al. Subchronic exposure of environmentally relevant concentrations of F-53B in mice resulted in gut barrier dysfunction and colonic inflammation in a sex-independent manner [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2019, 253: 268-277

[55] Pan Y, Wen B, Zhang H N, et al. Comparison of 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate (6:2 Cl-PFESA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) accumulation and toxicity in mung bean [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 287: 117332

[56] Shi Y L, Vestergren R, Xu L, et al. Human exposure and elimination kinetics of chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acids (Cl-PFESAs) [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2016, 50(5): 2396-2404

[57] Wang X P, Wang Y X, Li J G, et al. Occurrence and dietary intake of perfluoroalkyl substances in foods of the residents in Beijing, China [J]. Food Additives &Contaminants Part B, Surveillance, 2021, 14(1): 1-11

[58] Jin Q, Ma J H, Shi Y L, et al. Biomonitoring of chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acid in the general population in central and Eastern China: Occurrence and associations with age/sex [J]. Environment International, 2020, 144: 106043

[59] Xie L N, Wang X C, Dong X J, et al. Concentration, spatial distribution, and health risk assessment of PFASs in serum of teenagers, tap water and soil near a Chinese fluorochemical industrial plant [J]. Environment International, 2021, 146: 106166

[60] Sheng N, Wang J H, Guo Y, et al. Interactions of perfluorooctanesulfonate and 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate with human serum albumin: A comparative study [J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2020, 33(6): 1478-1486

[61] Chu C, Zhou Y, Li Q Q, et al. Are perfluorooctane sulfonate alternatives safer? New insights from a birth cohort study [J]. Environment International, 2020, 135: 105365

[62] 高雪嫣, 王雨昕, 李敬光, 等. 天津市孕妇全氟有机化合物的暴露水平[J]. 中国卫生工程学, 2019, 18(2): 166-170

Gao X Y, Wang Y X, Li J G, et al. Exposure of perfluoroalkyl substances in serum of pregnant women in Tianjin [J]. Chinese Journal of Public Health Engineering, 2019, 18(2): 166-170 (in Chinese)

[63] Jin H B, Mao L L, Xie J H, et al. Poly- and perfluoroalkyl substance concentrations in human breast milk and their associations with postnatal infant growth [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 713: 136417

[64] Pan Y T, Zhu Y S, Zheng T Z, et al. Novel chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonates and legacy per-/polyfluoroalkyl substances: Placental transfer and relationship with serum albumin and glomerular filtration rate [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2017, 51(1): 634-644

[65] Chen F F, Yin S S, Kelly B C, et al. Chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acids in matched maternal, cord, and placenta samples: A study of transplacental transfer [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2017, 51(11): 6387-6394

[66] Liu H X, Pan Y T, Jin S N, et al. Associations of per-/polyfluoroalkyl substances with glucocorticoids and progestogens in newborns [J]. Environment International, 2020, 140: 105636

[67] Yang R J, Liu S Y, Liang X X, et al. F-53B and PFOS treatments skew human embryonic stem cell in vitro cardiac differentiation towards epicardial cells by partly disrupting the WNT signaling pathway [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 261: 114153

[68] Sheng N, Cui R N, Wang J H, et al. Cytotoxicity of novel fluorinated alternatives to long-chain perfluoroalkyl substances to human liver cell line and their binding capacity to human liver fatty acid binding protein [J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2018, 92(1): 359-369

[69] Li C H, Jiang L D, Jin Y, et al. Lipid metabolism disorders effects of 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate through Hsa-miRNA-532-3p/Acyl-CoA oxidase 1(ACOX1) pathway [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2021, 228: 113011

[70] Ding D, Song X, Wei C L, et al. Efficient sorptive removal of F-53B from water by layered double hydroxides: Performance and mechanisms [J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 252: 126443

[71] Gao Y X, Deng S B, Du Z W, et al. Adsorptive removal of emerging polyfluoroalky substances F-53B and PFOS by anion-exchange resin: A comparative study [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2017, 323(Pt A): 550-557

[72] 巫秀玲, 赵晓祥, 孙铸宇. 金属材料协同VB12催化卤代有机物降解研究进展[J]. 化工进展, 2022, 41(2): 708-720

Wu X L, Zhao X X, Sun Z Y. Catalytic degradation of halogenated organic compounds by synergistic system of metal materials and VB12: A review [J]. Chemical Industry and Engineering Progress, 2022, 41(2): 708-720 (in Chinese)

[73] Gantzer Charles J, Wackett Lawrence P. Reductive dechlorination catalyzed by bacterial transition-metal coenzymes [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 1991, 25(4): 715-722

[74] Amir A, Lee W. Enhanced reductive dechlorination of tetrachloroethene during reduction of cobalamin (Ⅲ) by nano-mackinawite [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2012, 235-236: 359-366

[75] Lin Y F, Ruan T, Liu A F, et al. Identification of novel hydrogen-substituted polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonates in environmental matrices near metal-plating facilities [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2017, 51(20): 11588-11596

[76] Yi S J, Morson N, Edwards E A, et al. Anaerobic microbial dechlorination of 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorooctane ether sulfonate and the underlying mechanisms [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2022, 56(2): 907-916

[77] Yi S J, Zhu L Y, Mabury S A. First report on in vivo pharmacokinetics and biotransformation of chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonates in rainbow trout [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2020, 54(1): 345-354

[78] Cao H M, Zhang W L, Wang C P, et al. Photodegradation of F-53B in aqueous solutions through an UV/Iodide system [J]. Chemosphere, 2022, 292: 133436

[79] Cui J K, Gao P P, Deng Y. Destruction of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) with advanced reduction processes (ARPs): A critical review [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2020, 54(7): 3752-3766

[80] 张振国, 刘希涛, 赖玲, 等. 机械化学法降解氯代有机污染物的研究进展[J]. 化工进展, 2021, 40(1): 487-504

Zhang Z G, Liu X T, Lai L, et al. Progress in degradation of chlorinated organic pollutants by mechanochemical method [J]. Chemical Industry and Engineering Progress, 2021, 40(1): 487-504 (in Chinese)

[81] Yan X, Liu X T, Qi C D, et al. Mechanochemical destruction of a chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate (F-53B, a PFOS alternative) assisted by sodium persulfate [J]. RSC Advances, 2015, 5(104): 85785-85790

[82] Zhang K L, Cao Z G, Huang J, et al. Mechanochemical destruction of Chinese PFOS alternative F-53B [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2016, 286: 387-393

[83] Zhuo Q F, Wang J B, Niu J F, et al. Electrochemical oxidation of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) substitute by modified boron doped diamond (BDD) anodes [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020, 379: 122280