重金属污染是目前世界范围内最严重的环境问题之一。多种重金属在美国有毒物质与疾病登记署和环境保护局颁布的危害物质名录(The Priority List of Hazardous Substances)上名列前茅,其中砷(arsenic, As)位于环境污染物的首位(https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/spl/index.html)。砷是一种天然存在的有毒类金属元素,是危害最严重的环境污染物之一,几乎存在于所有的环境介质中。美国毒物和疾病登记署(ATSDR)将其列为对人类健康危害最大的有毒物质,世界卫生组织(WHO)也将其列为引起全球重大公共卫生关注的化学物质。砷具有高毒性、致畸、致癌等危害。据报道,印度和孟加拉等国多处地区均发现与砷污染有关的大面积长期中毒事件,当地居民备受砷中毒疾病的折磨与煎熬[1-2]。2013年,据国际权威期刊报道,砷污染对约2 000万中国人造成健康危害,对中国砷污染提出预警[3]。据世界卫生组织报道,目前全球至少有5 000多万人口正面临着地方性砷中毒的威胁,提醒公众警惕砷中毒。

砷污染是我国近海最严重的环境问题之一,各种来源的砷通过陆地径流、大气沉降、排污口和海洋倾废等途径汇入海洋。不同来源的砷汇入海洋生态系统,进入海洋食物链,传递至海洋鱼类,最终对人类健康构成严重威胁,导致砷对海洋生态系统的污染成为一个重要的国际性健康和环境问题[4]。海洋的承载力是有限的,当污染物排放超过海洋环境承载力时,就会引发海洋生态环境安全问题。砷污染影响着全球115个国家,已经在中国、南亚和东南亚(如巴基斯坦、孟加拉国、尼泊尔和印度)等地成为严重的环境问题,而这一区域刚好位于“南海-印度洋”,它是中国“21世纪海上丝绸之路”重要战略区域。砷在海洋环境中存在着多种化学形态,已经鉴定了20多种不同的无机和有机形态砷,前者包括三价砷(arsenite, As(III))和五价砷(arsenate, As(Ⅴ)),后者包括一甲基砷酸(monomethylarsonic acid, MMA)、二甲基砷酸(dimethylarsinic acid, DMA)、砷甜菜碱(arsenobetaine, AsB)和砷胆碱(arsenocholine, AsC)等。无机砷具有剧毒,甲基砷(MMA和DMA)毒性减弱,而AsB和AsC毒性极小或无毒[5]。

海产品是人类砷摄入的主要来源[6]。在西班牙的一项研究中,发现大多数人接触砷的途径是海产品,这种来源占砷暴露总量的96%[7]。AsB主要通过砷在鱼类、软体动物和甲壳类动物等海洋生物中代谢而形成[8-9]。AsB是海产品中砷的主要存在形式,通常占鱼类总砷的90%以上[10-12]。海产品中的总砷(AsB>90%)浓度可能比食品中的砷限值(50 ng·g-1)高出200倍[13]。通过食用海产品,人类摄入大量的AsB,从而AsB进入人类食物链[14-17]。根据联合国粮食及农业组织(粮农组织)发布的《世界渔业和水产养殖状况》,2016年鱼类总产量高于往年,人类直接消费了151亿t[18]。因此,通过消费鱼类,AsB是人类摄入的主要砷化合物。

AsB被认为是海洋食物链中砷代谢的最终产物,是海洋生态系统中砷循环的终点,是人类摄入的主要砷形态,但对其生物合成和降解的机理认识仍然缺乏[6, 19-27]。一方面,从解毒的角度,从低等微生物到海洋鱼类,许多酶在剧毒的无机砷向无毒的AsB生物转化中发挥重要作用。尽管已经提出了关于其生物合成途径的各种推测,海洋生物中AsB的合成途径尚不清楚[14, 28]。另一方面,从食品安全的角度,AsB在哺乳动物和人体内是否会降解为毒性更强的无机砷,AsB对人体是否会产生毒性危害呢?这些问题仍不清楚。因此,海产品中AsB的合成途径以及人类从海产品中摄入AsB的降解过程仍有待挖掘,最终是否会导致生态和健康风险仍有待深入探究。

本文对AsB在海产品和哺乳动物体内的生物转化(合成和降解)过程进行了综述,有助于了解AsB的潜在生态和健康风险,从而加深我们对AsB在海产品和哺乳动物中的毒理循环的认识。剖析它们对认识AsB从海洋鱼类到哺乳动物的传递规律,特别在人类体内的代谢过程具有重要意义,而且为解决海产品砷污染以及造成的人类健康危害问题提供相应的理论支持,为最终采取防范措施,防控生态和人体砷暴露具有重要的现实指导意义。本综述为砷在毒理学和环境化学领域的进一步研究提供了有益的资源。

1 海洋生物体内高砷甜菜碱富集原因和可能的合成途径(Causes and possible synthetic pathways of high arsenobetaine in marine organisms)

1.1 海洋生物体内高砷甜菜碱富集原因(Causes of high arsenobetaine in marine organisms)

海产品的质量状况一直为社会大众所关注。海洋鱼类体内总砷浓度(1~1 000 μg·g-1)比淡水鱼类总砷浓度(<1 μg·g-1)高1~3个数量级,表现出较高的砷富集能力[8, 28-29]。我们对我国沿海野生海洋鱼类砷含量进行了由北至南的大范围调查,评估了中国沿海野生鱼类砷富集状况,发现中国沿海部分海洋底栖鱼类短吻红舌鳎(Cynoglossus joyneri)和孔虾虎鱼(Trypauchen vagina)肌肉组织中砷含量严重超标,其中湛江的孔虾虎鱼肌肉组织中砷含量超过我国制定的安全标准30倍之多,长期摄食会对人体健康造成潜在危害,揭示中国沿海海洋鱼类体内存在高砷富集状况。海洋鱼类具有高砷富集现象,AsB是海洋鱼类体内主要的砷存在形态,占总砷的90%以上[29-35]。AsB同样是海洋甲壳类和软体动物组织中主要的砷存在形态,占总砷的50%~95%[30]。AsB在其他海洋生物,比如多毛类、甲壳类、双壳类、腹足类、头足类,同样占总砷的大部分[36]。因此,AsB是海洋生物体内主要的存在形态。

AsB在海洋生物体内高累积的原因到底是什么?首先,砷的生物累积随着盐度的增加而增加,研究发现贝类动物可以有效从海水中吸收AsB,而虾和鱼等高等动物只可从食物中(包括浮游植物等)积累AsB[37-38]。远洋鱼类中发现总砷随盐度增加的趋势,主要以AsB形式存在,表明盐度与AsB的吸收和累积密切相关[17, 37]。阿拉伯湾西部的对虾(Penaeus semiisulcatus)和长须鱼(Arius thalassinus)中总砷和AsB含量相对较高,可能是由于海湾西部相对较高的盐度所致[39]。AsB的滞留取决于周围水的盐度,表明AsB可以部分替代重要的细胞渗透物甜菜碱(一种渗透压调节代谢物)[29, 40]。我们发现海洋鱼类中AsB含量与环境盐度显著正相关,盐度可以控制砷的迁移,是关键控制因子,可能由于AsB是甜菜碱的结构类似物,可帮助海洋鱼类抵抗高盐海水的胁迫[29]。因此,盐度与海洋生物体内AsB的累积密切相关。虽然AsB含量与环境盐度有关系,而盐度调控鱼类砷生物转化机制研究匮乏。现有研究大多局限于对海洋和淡水鱼类砷不同形态与盐度野外调查现象的描述,而对规律与调控机制的认识尚不足。

第二,通过研究砷沿着不同食物链传递过程,植食性食物链(大型海藻石莼(Ulva lactuca)、龙须菜(Gracilaria lemaneiformis)和粗江蓠(Gracilaria gigas)—黄斑篮子鱼(Siganus fuscescens))、肉食性食物链(沙蚕(Nereis succinea)、牡蛎(Saccostrea cucullata)和蛤(Asaphis violascens)—鲈鱼(Lateolabrax japonicus))和海洋底栖食物链(沉积物—沙蚕(N. succinea)和蛤(A. violascens)—诸氏鲻虾虎鱼(Mugilogobius chulae))。发现砷在沿这3类食物链传递过程中,食物中的无机砷较难被鱼体吸收,并且它们在鱼体(黄斑篮子鱼、鲈鱼和诸氏鲻虾虎鱼)组织中被生物转化成有机砷而不是直接累积;然而,食物中的AsB可以直接通过鱼体消化器官的上皮细胞膜,容易被鱼体吸收,而且是砷在鱼体组织中最终的存储形式。因此,不同形态砷沿食物链传递过程中,AsB比无机砷更容易沿食物链传递和吸收,AsB的生物可利用性比无机砷高[33, 41]。我们运用放射性同位素(73As)示踪技术和先进理论模型-药代动力学模型(PBPK),研究了砷在海洋鱼类体内的生物转运过程,通过PBPK模拟发现,交换率(k)(水到鳃)比k(水到肠道)低2倍,而且血液与鳃之间有最高的交换率,表明鳃不是主要的吸收器官。k(血液到肠道)(2.69 d-1)是k(肠道到血液)(0.0039 d-1)的700倍,表明AsB更容易分布于肠道,肠道是主要的吸收器官。同时,在暴露过程中,肠道中As(Ⅴ)(38.8%~45.1%)是主要形态,而在净化过程中AsB(81.7%~96.0%)成为主要形态,而且AsB在肠道中的含量比在肝脏中高,表明肠道是无机砷转化为AsB的主要代谢器官。肠道是砷的主要吸收和转化合成AsB的器官。肠道吸收的不同形态砷,由血液转运至头、鳃、肝脏、肌肉各组织,最终主要以AsB形式贮存于靶器官肌肉组织中。因此,解析了肠道中合成的AsB和肌肉中存储的AsB是海洋鱼类高砷富集的主要原因[42]。罗非鱼(Oreochromis mossambicus)肠道菌能够促进鱼类砷代谢,分离并鉴定出影响鱼类砷代谢的关键肠道菌嗜麦芽寡养单胞菌(Stenotrophomonas maltophilia SCSIOOM),其能合成AsB,而且betIBA调控S. maltophilia SCSIOOM体内AsB的合成[43]。同时,我们解析了AsB和As(Ⅴ)在海洋鱼类不同组织器官之间显著的生物转运差异,精确揭示了AsB的吸收、肝肠循环、存储和排泄过程,As(Ⅴ)表现出快速通过肠道膜、快速转运和排出的能力,而AsB通过肠道膜的能力较弱,被缓慢吸收并最终储存在肌肉中[44]。

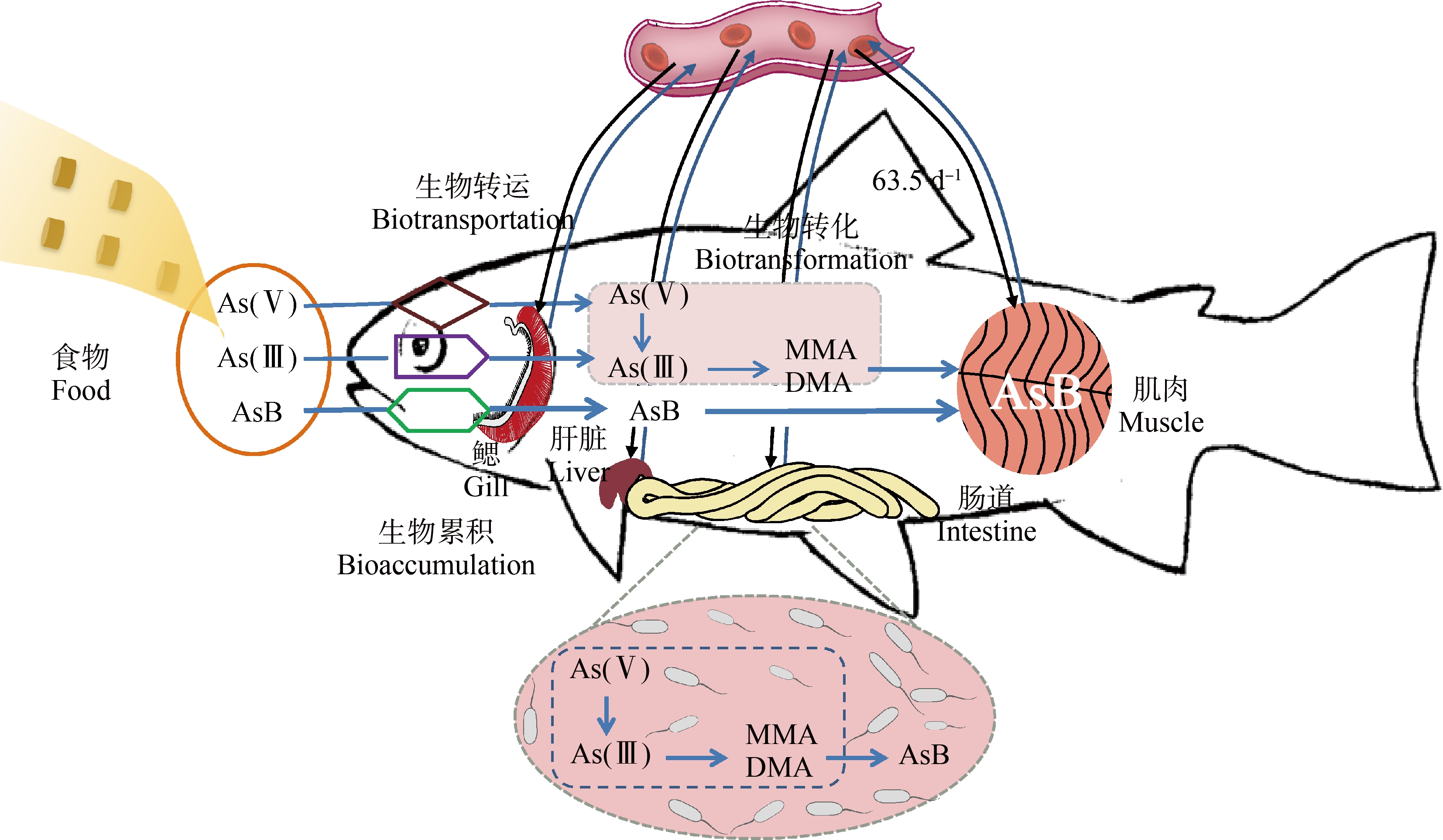

综上所述,海洋生物,特别是海洋鱼类具有高AsB富集能力,主要归因于AsB的累积与环境盐度密切相关,食物中AsB比无机砷更容易沿食物链传递和吸收,肠道是砷的主要吸收和转化合成AsB的器官,AsB穿过肠道膜的能力较弱,缓慢吸收,循环和存储在肌肉组织中,生物转化和转运对AsB的富集起决定性作用。因此,无机砷在肠道中合成AsB,食物中和合成的AsB缓慢穿过肠道膜,缓慢循环以及高的肌肉存储速率是导致海洋鱼类高AsB富集的主要原因(图1)。然而,AsB的合成细节和途径尚未完全解析。

图1 海洋鱼类高AsB富集原因示意图

注:AsB表示砷甜菜碱,MMA表示一甲基砷,DMA表示二甲基砷。

Fig. 1 Schematic diagram of causes of high AsB concentrations in marine fish

Note: AsB means arsenobetaine, MMA means monomethylarsonic acid, and DMA means dimethylarsinic acid.

1.2 海洋生物体内砷甜菜碱可能的合成途径(Possible synthesis pathways of arsenobetaine in marine organisms)

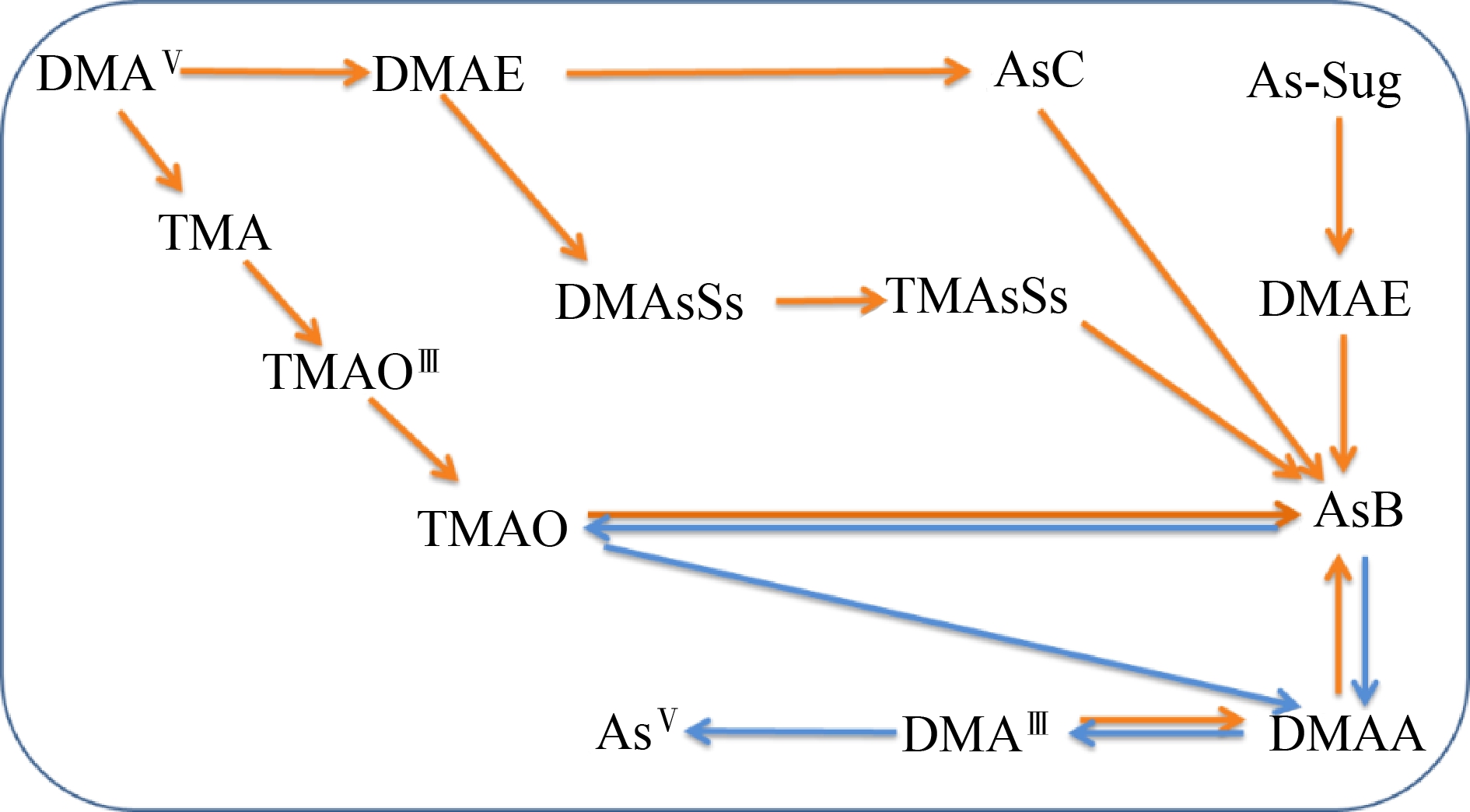

目前关于AsB合成的过程主要依赖于潜在的生物合成前体和中间体的检测[45]。在不同生物体内,AsB有几种可能的合成途径:(1)从二甲基化砷糖(DMAsSs)或三甲基化砷糖(TMAsSs)合成AsB。据推测,DMAsSs通过二甲基砷钠乙醇(DMAE)和二甲基砷钠乙酸(DMAA)转化为AsB,而TMAsSs直接转化为AsB[46]。(2)从AsC转化为AsB。沉积物中的微生物可以将AsC转化为AsB[47],微生物枯草杆菌(B. subtilis)也可以将AsC转化为AsB[1],AsC是AsB的关键前体[48]。在水生动物中只发现微量的AsC[49-50],这表明它主要作为一种代谢中间物存在。AsC是AsB的代谢前体,接种标记AsC后,在水生鱼类和贻贝中迅速吸收并转化为AsB[51-54]。(3)DMAE和AsC共同决定AsB的合成。DMAE作为中间体,甲基化生成AsC,然后氧化生成AsB。另外,DMAE可能被氧化形成DMAA,然后甲基化形成AsB[55]。此外,三甲基二氧砷基核糖苷可以定量转化为AsC,而AsC又可以定量转化为AsB[50, 56]。(4)假设AsB由DMAIII、2-氧酸、糖基酸和丙酮酸合成,从而形成DMAA和AsB[14, 46]。AsB也由DMAIII合成,DMAA的前体(可能由乙醛酸或丙酮酸合成),然后在海洋生物中甲基化形成AsB[57]。因此,通过已有研究发现,在水生生物体内AsB最有可能来源于AsC。

微生物可能参与AsB的合成。已有研究报道了海洋和土壤细菌对AsB的代谢[56, 58-60]。AsB是由海洋沉积物中砷糖的微生物降解形成的,导致中间产物(如DMAE),随后可能被食腐动物和食草动物消耗,导致AsB的合成[50, 61]。细菌假单胞菌(Pseudomonas sp.)在海洋生物中可将二甲基胂基醋酸盐转化为AsB[62]。在生物体中发现的砷形态,二甲基砷核糖苷、硫砷核糖苷和三甲基砷核糖苷的降解也可能形成AsB[63-64]。因此,AsB合成的可能生物转化途径(图2),其中一些关键中间体、关键合成蛋白和基因尚未确定,微生物可能在AsB合成过程中发挥重要的作用,仍有待深入探究。

图2 已知和推测的AsB合成和降解过程

注:DMAE表示二甲基砷钠乙醇,AsC表示砷胆碱,DMAsSs表示二甲基化砷糖,TMAsSs表示三甲基化砷糖,DMAA表示二甲基砷钠乙酸,TMA表示四甲基砷,TMAO表示氧化三甲胺。

Fig. 2 Known and presumed processes of AsB synthesis and degradation

Note: DMAE means dimethylarsinoylethanol, AsC means arsenocholine, DMAsSs means dimethylated arsenosugars, TMAsSs means trimethylated arsenosugars, DMAA means dimethylarsinoyl acetic acid, TMA means tetramethyl arsine, and TMAO means trimethylarsine oxide.

2 哺乳动物体内的砷甜菜碱代谢过程(Arsenobetaine metabolism processes in mammals)

目前,海产品中的AsB在哺乳动物中的转化仍存在争议。关于人体中AsB的吸收和代谢仍了解尚少[51]。尽管无机砷在哺乳动物中的生物分布、生物转化和毒性已被广泛研究,但对AsB在哺乳动物中的生物转化知之甚少[65-66]。人体中几个关于砷代谢的基本假设如下。

(1)哺乳动物体内没有形成AsB。在小鼠和人类体内几乎没有AsB的生成[66-67]。(2)哺乳动物体内形成AsB。在无AsB的饮食中,3/5的志愿者的尿液中检测到AsB,AsB浓度范围为0.2~12 μg·L-1。AsB累积的可能原因有2个:组织中累积的AsB释放缓慢和从大米中摄取的无机砷形成AsB[68]。(3)哺乳动物体内吸收的AsB排泄得快和完全,且形态无改变。通过口服给药后,AsB通过胃肠道被有效地吸收,大部分通过尿液被排泄,而且形态没有发生变化[69-70]。经口摄入的AsB,在小鼠、大鼠和兔子的胃肠道中几乎完全吸收,但在体内不经代谢以尿液排出,98.5% AsB在2 d内被排出体外[70]。小鼠、大鼠、兔子和仓鼠口服AsB后,在它们体内不代谢,但几乎完全从胃肠道吸收,并通过尿液不加改变地排出[71-72]。人体摄入AsB不会增加尿液中无机砷、MMA或DMA的浓度,支持AsB没有代谢、通过尿液排泄的假设[73]。志愿者只食用含有AsB的海产品,之后他们的排泄物(粪便和尿液)样本中只检测到AsB[68, 74]。摄入的AsB快速通过尿液排泄出人体外,而且形态没有改变,从而减轻健康危害[15-17]。(4)在哺乳动物体内,AsB是否会降解为毒性更强的甲基砷和无机砷(图2)?也有研究报道少量的AsB发生了代谢[75-76]。每天给大鼠注射AsB,7个月后,AsB部分代谢为四甲基铵(TeMA)和氧化三甲胺(TMAO)[76]。AsB在有氧系统中与人类粪便一起共存7 d后,降解为DMAA、DMA和TMAO[60]。AsB处理大鼠4 d后,其尿液中检测到TeMA、AsB和TMAO,推测这一降解过程可能是由大鼠盲肠中的肠道微生物介导的[77]。我们最新的研究发现,小鼠长期暴露AsB,可导致AsB和As(Ⅴ)在小鼠组织中积累。AsB在吸收前被降解为As(Ⅴ),然后通过血液循环运输到其他组织。虽然吸收和生物转化受肠道微生物的调控,但aqp7、sam和as3mt基因以及去甲基化和甲基化过程在小鼠肠道组织中存在。基因、微生物组和代谢组学分析表明,葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus)和真杆菌(Blautia)、花生四烯酸、胆碱和鞘氨醇参与了小鼠肠道中AsB向As(Ⅴ)的降解。因此,长期食用AsB会增加小鼠体内As(Ⅴ)含量。通过食用海鱼长期摄入AsB可能对人类健康造成潜在危害[78]。因此,我们的研究结果引起了人们对人类从海鱼中长期摄入砷的健康危害的高度关注。为水产品安全和人类健康风险提供了早期预警。未来的研究亟待探究消费海洋食物如何增加甲基砷和无机砷的负担。

小鼠体内的微生物组成与人体内的差异很大,可能对AsB在人体内的降解过程有影响。因此,人体微生物在AsB生物降解过程中的作用有待进一步研究。需要注意的是,人类本身可能没有将AsB降解的能力,但是肠道微生物可能在这个过程中发挥着重要的作用。AsB可以在人类胃肠道中被微生物转化,DMA和TMAO是主要的降解产物[79]。在模拟胃肠消化过程中MMA和DMA的去甲基化被发现[80]。人类食用海产品中的AsB,可被微生物降解为毒性较高的砷形态[59]。人肠道中的微生物可以将AsB转化为各种甲基化的砷化合物,从而潜在地形成有毒的代谢产物。在与肠道菌群进行体外温育后,有氧肠道细菌在7 d后将AsB分解为DMA、DMAA和TMAO,但降解的AsB在30 d后会再次出现在样品中,研究表明人类肠道内存在能够降解AsB的微生物,然而,转化所需的时间比生理肠道的通过时间长得多,因此,在体内尚未观察到[60]。因此,哺乳动物和人类肠道中的微生物在AsB的降解过程中发挥了重要的作用。

3 环境中微生物在砷甜菜碱降解过程中发挥的作用(The role of environmental microorganisms in the degradation of arsenobetaine)

AsB的微生物转化不限于哺乳动物和人类微生物群。环境细菌在环境中AsB及其代谢产物的循环中起关键作用。在海洋生态系统中,已经进行了许多有关微生物AsB降解的研究[81]。Hanaoka等[82]研究AsB在海洋环境中的命运,来自海洋沉积物的微生物首先将AsB降解为TMAO,然后降解为MMA或As(Ⅴ)。在海洋环境中,微生物多样性是降解AsB的关键,好氧微生物促进了AsB向TMAO的转化,而当消化系统中的微生物在液体培养物中培养时,AsB代谢为DMA和DMAA,而不是TMAO,表明存在不同的AsB降解途径,其取决于微生物群落的组成[59, 83]。在混合了海洋沉积物的ZoBell介质中,发现了AsB降解为TMAO,并进一步转化为As(Ⅴ)的过程[84]。AsB也被降解为TMAO、DMA和As(Ⅴ)。DMAA被证明是AsB降解为DMA的中间产物[59, 85]。AsB在数小时内转化,最初转化为二甲基胂基醋酸盐,然后转化为DMA[85]。在海洋微生物混合培养的作用下,已检测到AsB的生物转化[58]。基于不同中间体的形成,提出了不同降解AsB途径[85]。AsB降解为无机砷有2种途径(TMAO或DMAA)。不同的AsB降解途径取决于微生物群落的组成[27]。已从土壤和水中分离出去甲基化微生物[48, 83, 86-87]。因此,环境微生物在AsB的降解过程中同样发挥了重要作用。

AsB的合成和降解是一个复杂的过程,而且受到众多基因的调控。从目前砷代谢相关基因的研究结果来看,As3MT、PNP、GSTM1、GSTT1和MTHFR等基因的多态性都与砷代谢有一定的相关性。砷暴露后转录活性的改变导致基因表达的显著变化,表明基因对砷代谢存在不同的调控途径[88],比如As3MT基因对砷代谢存在不同调控方式[89]。因此,如果要彻底研究清楚AsB的合成和降解过程,利用当前和未来的宏基因组学、元转录组学、宏蛋白质组学和代谢组学方法破译微生物砷生物转化过程,将提高我们对微生物如何促进AsB生物转化过程的理解[90]。因此,关于AsB的生物转化过程,包括甲基化、AsB合成和降解AsB,应用基因组学方法,特别是相关酶和基因的鉴定,尚有很多亟待探索的未知过程。

4 结语和展望(Conclusion and outlook)

由于砷在环境中普遍存在及其与各种人类疾病的关系,引起了全球对其公共卫生影响的关注。本综述重点讨论了AsB的生物转化(合成和降解)过程,对于深入了解AsB在环境中的命运及评估其对人体健康的风险至关重要。同时,了解影响AsB转化过程是制定降低砷暴露健康风险的关键策略。该研究领域未来的研究趋势主要集中在以下几个方面:

(1)需要深入研究AsB的环境命运和代谢途径,开发先进的分析技术,用以对各种砷化合物之间的转化进行全方面的研究;(2)确定微生物和非生物介导的AsB合成和降解过程;(3)AsB降解为无机砷会增加其毒性,更多研究应着眼于转化动力学,以更好地理解环境中的砷循环;(4)海洋生物可以将有毒的无机砷转化为无毒的AsB,但其合成途径尚不清楚;微生物在AsB的降解过程中发挥重要作用,但其分子转化机制尚不清楚,因此,利用基因组学方法深入研究AsB的合成和降解过程至关重要。

因此,了解AsB在海洋生物、哺乳动物和人类组织中的合成和降解有助于控制其在环境中的迁移循环过程,对于防控砷污染和降低人类健康危害至关重要。将砷的环境行为研究经验,用于预测环境如何改变砷。相应的,砷的生物转化如何改变环境?总之,AsB的来源、生物合成、降解和命运需要继续深入探究,才能更全面解析AsB的合成途径和代谢过程。

[1] Acharyya S K, Chakraborty P, Lahiri S, et al. Arsenic poisoning in the Ganges delta [J]. Nature, 1999, 401(6753): 545-547

[2] Stokstad E. Bangladesh. Agricultural pumping linked to arsenic [J]. Science, 2002, 298(5598): 1535-1537

[3] Rodríguez-Lado L, Sun G F, Berg M, et al. Groundwater arsenic contamination throughout China [J]. Science, 2013, 341(6148): 866-868

[4] Lin M C, Liao C M. Assessing the risks on human health associated with inorganic arsenic intake from groundwater-cultured milkfish in southwestern Taiwan [J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2008, 46(2): 701-709

[5] Moe B, Peng H Y, Lu X F, et al. Comparative cytotoxicity of fourteen trivalent and pentavalent arsenic species determined using real-time cell sensing [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2016, 49: 113-124

[6] Luvonga C, Rimmer C A, Yu L L, et al. Organoarsenicals in seafood: Occurrence, dietary exposure, toxicity, and risk assessment considerations - A review [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020, 68(4): 943-960

[7] Fontcuberta M, Calderon J, Villalbí J R, et al. Total and inorganic arsenic in marketed food and associated health risks for the Catalan (Spain) population [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59(18): 10013-10022

[8] Zhang W, Wang W X. Large-scale spatial and interspecies differences in trace elements and stable isotopes in marine wild fish from Chinese waters [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2012, 215-216: 65-74

[9] Zhang W, Wang W X, Zhang L. Arsenic speciation and spatial and interspecies differences of metal concentrations in mollusks and crustaceans from a South China Estuary [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2013, 22(4): 671-682

[10] Amlund H, Ingebrigtsen K, Hylland K, et al. Disposition of arsenobetaine in two marine fish species following administration of a single oral dose of[14C]arsenobetaine [J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Toxicology &Pharmacology, 2006, 143(2): 171-178

[11] Sele V, Sloth J J, Lundebye A K, et al. Arsenolipids in marine oils and fats: A review of occurrence, chemistry and future research needs [J]. Food Chemistry, 2012, 133(3): 618-630

[12] Wolle M M, Conklin S D. Speciation analysis of arsenic in seafood and seaweed: Part Ⅰ—Evaluation and optimization of methods [J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2018, 410(22): 5675-5687

[13] Sakurai T, Kojima C, Ochiai M, et al. Evaluation of in vivo acute immunotoxicity of a major organic arsenic compound arsenobetaine in seafood [J]. International Immunopharmacology, 2004, 4(2): 179-184

[14] Caumette G, Koch I, Reimer K J. Arsenobetaine formation in plankton: A review of studies at the base of the aquatic food chain [J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2012, 14(11): 2841-2853

[15] Molin M, Ulven S M, Meltzer H M, et al. Arsenic in the human food chain, biotransformation and toxicology-Review focusing on seafood arsenic [J]. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, 2015, 31: 249-259

[16] Thomas D J, Bradham K. Role of complex organic arsenicals in food in aggregate exposure to arsenic [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2016, 49: 86-96

[17] Taylor V, Goodale B, Raab A, et al. Human exposure to organic arsenic species from seafood [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 580: 266-282

[18] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of the World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals [R]. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2018: 6

[19] Francesconi K A, Hunter D A, Bachmann B, et al. Uptake and transformation of arsenosugars in the shrimp Crangon crangon [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 1999, 13(10): 669-679

[20] Francesconi K A, Khokiattiwong S, Goessler W, et al. A new arsenobetaine from marine organisms identified by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry [J]. Chemical Communications, 2000(12): 1083-1084

[21] Madsen A D, Goessler W, Pedersen S N, et al. Characterization of an algal extract by HPLC-ICP-MS and LC-electrospray MS for use in arsenosugar speciation studies [J]. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry, 2000, 15(6): 657-662

[22] Anita G, Somkiat K, Walter G, et al. Identification of the new arsenic-containing betaine, trimethylarsoniopropionate, in tissues of a stranded sperm whale Physeter catodon [J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2002, 82(1): 165-168

[23] Grotti M, Soggia F, Lagomarsino C, et al. Arsenobetaine is a significant arsenical constituent of the red Antarctic alga Phyllophora antarctica [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2008, 5(3): 171-175

[24] Taylor V F, Jackson B P, Siegfried M, et al. Arsenic speciation in food chains from mid-Atlantic hydrothermal vents [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2012, 9(2): 130-138

[25] Maher W A, Foster S, Krikowa F, et al. Thio arsenic species measurements in marine organisms and geothermal waters [J]. Microchemical Journal, 2013, 111: 82-90

[26] Hoffmann T, Warmbold B, Smits S H J, et al. Arsenobetaine: An ecophysiologically important organoarsenical confers cytoprotection against osmotic stress and growth temperature extremes [J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2018, 20(1): 305-323

[27] Chen J, Garbinski L D, Rosen B, et al. Organoarsenical compounds: Occurrence, toxicology and biotransformation [J]. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2020, 50(3): 217-243

[28] Ciardullo S, Aureli F, Raggi A, et al. Arsenic speciation in freshwater fish: Focus on extraction and mass balance [J]. Talanta, 2010, 81(1-2): 213-221

[29] Zhang W, Guo Z Q, Song D D, et al. Arsenic speciation in wild marine organisms and a health risk assessment in a subtropical bay of China [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 626: 621-629

[30] 杜森, 张黎. 砷在海洋食物链中的生物放大潜力及发生机制探讨[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2019, 14(1): 54-66

Du S, Zhang L. Biomagnification potential and the mechanisms of arsenic in marine food chains [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2019, 14(1): 54-66 (in Chinese)

[31] Zhang W, Chen L Z, Zhou Y Y, et al. Biotransformation of inorganic arsenic in a marine herbivorous fish Siganus fuscescens after dietborne exposure [J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 147: 297-304

[32] Zhang W, Guo Z Q, Zhou Y Y, et al. Comparative contribution of trophic transfer and biotransformation on arsenobetaine bioaccumulation in two marine fish [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2016, 179: 65-71

[33] Zhang W, Wang W X, Zhang L. Comparison of bioavailability and biotransformation of inorganic and organic arsenic to two marine fish [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2016, 50(5): 2413-2423

[34] Zhang W, Huang L M, Wang W X. Biotransformation and detoxification of inorganic arsenic in a marine juvenile fish Terapon jarbua after waterborne and dietborne exposure [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2012, 221: 162-169

[35] Bears H, Richards J G, Schulte P M. Arsenic exposure alters hepatic arsenic species composition and stress-mediated gene expression in the common killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus) [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2006, 77(3): 257-266

[36] 赵艳芳, 尚德荣, 宁劲松, 等. 水产品中不同形态砷化合物的毒性研究进展[J]. 海洋科学, 2009, 33(9): 92-96

Zhao Y F, Shang D R, Ning J S, et al. Researches on the toxicity of arsenic species in seafood [J]. Marine Sciences, 2009, 33(9): 92-96 (in Chinese)

[37] Larsen Erik H, Francesconi Kevin A. Arsenic concentrations correlate with salinity for fish taken from the North Sea and Baltic waters [J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2003, 83(2): 283-284

[38] Clowes L A, Francesconi K A. Uptake and elimination of arsenobetaine by the mussel Mytilus edulis is related to salinity [J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology &Pharmacology, 2004, 137(1): 35-42

[39] Krishnakumar P K, Qurban M A, Stiboller M, et al. Arsenic and arsenic species in shellfish and finfish from the western Arabian Gulf and consumer health risk assessment [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 566-567: 1235-1244

[40] Whaley-Martin K J, Koch I, Reimer K J. Arsenic species extraction of biological marine samples (Periwinkles, Littorina littorea) from a highly contaminated site [J]. Talanta, 2012, 88: 187-192

[41] Zhang W, Wang W X. Arsenic biokinetics and bioavailability in deposit-feeding clams and polychaetes [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 616-617: 594-601

[42] Zhang W, Song D D, Tan Q G, et al. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for the biotransportation of arsenic in marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2020, 54(12): 7485-7493

[43] Song D D, Chen L Z, Zhu S Q, et al. Gut microbiota promote biotransformation and bioaccumulation of arsenic in tilapia [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2022, 305: 119321

[44] Xiong H Y, Tan Q G, Zhang J C, et al. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model revealed the distinct bio-transportation and turnover of arsenobetaine and arsenate in marine fish [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2021, 240: 105991

[45] Popowich A, Zhang Q, Le X C. Arsenobetaine: The ongoing mystery [J]. National Science Review, 2016, 3(4): 451-458

[46] Kunito T, Kubota R, Fujihara J, et al. Arsenic in marine mammals, seabirds, and sea turtles [J]. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2008, 195: 31-69

[47] Edmonds J S, Francesconi K A, Hansen J A. Dimethyloxarsylethanol from anaerobic decomposition of brown kelp (Ecklonia radiata): A likely precursor of arsenobetaine in marine fauna [J]. Experientia, 1982, 38(6): 643-644

[48] Christakopoulos A, Norin H, Sandström M, et al. Cellular metabolism of arsenocholine [J]. Journal of Applied Toxicology, 1988, 8(2): 119-127

[49] Cullen W, Reimer K. Arsenic speciation in the environment [J]. Chemical Reviews, 1989, 89: 713-764

[50] Francesconi K A, Edmonds J S. Arsenic in the sea [J]. Oceanography and Marine Biology-An Annual Review, 1993, 31: 111-151

[51] Borak J, Hosgood H D. Seafood arsenic: Implications for human risk assessment [J]. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2007, 47(2): 204-212

[52] Marafante E, Vahter M, Dencker L. Metabolism of arsenocholine in mice, rats and rabbits [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 1984, 34(3): 223-240

[53] Gailer J, Lrgolic K J, Francesconi K A, et al. Metabolism of arsenic compounds by the blue mussel Mytilus edulis after accumulation from seawater spiked with arsenic compounds [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 1995, 9(4): 341-355

[54] Kaise T, Horiguchi Y, Fukui S, et al. Acute toxicity and metabolism of arsenocholine in mice [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 1992, 6: 369-373

[55] Foster S, Maher W. Arsenobetaine and thio-arsenic species in marine macroalgae and herbivorous animals: Accumulated through trophic transfer or produced in situ? [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 2016, 49: 131-139

[56] Devesa V, Loos A, Sú er M A, et al. Transformation of organoarsenical species by the microflora of freshwater crayfish [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2005, 53(26): 10297-10305

er M A, et al. Transformation of organoarsenical species by the microflora of freshwater crayfish [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2005, 53(26): 10297-10305

[57] Edmonds J S, Francesconi K A. Organoarsenic Compounds in the Marine Environment [M]// Craig P J. ed. Organometallic Compounds in the Environment. New York: Wiley, 2003: 195-222

[58] Hanaoka K, Uchida K, Tagawa S, et al. Uptake and degradation of arsenobetaine by the microorganisms occurring in sediments [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 1995, 9(7): 573-579

[59] Jenkins R O, Ritchie A W, Edmonds J S, et al. Bacterial degradation of arsenobetaine via dimethylarsinoylacetate [J]. Archives of Microbiology, 2003, 180(2): 142-150

[60] Harrington C F, Brima E I, Jenkins R O. Biotransformation of arsenobetaine by microorganisms from the human gastrointestinal tract [J]. Chemical Speciation &Bioavailability, 2008, 20(3): 173-180

[61] Kirby J, Maher W. Tissue accumulation and distribution of arsenic compounds in three marine fish species: Relationship to trophic position [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 2002, 16: 108-115

[62] Ritchie A W, Edmonds J S, Goessler W, et al. An origin for arsenobetaine involving bacterial formation of an arsenic-carbon bond [J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2004, 235(1): 95-99

[63] Francesconi K A, Goessler W, Panutrakul S, et al. A novel arsenic containing riboside (arsenosugar) in three species of gastropod [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 1998, 221(2-3): 139-148

[64] Kirby J, Maher W, Spooner D. Arsenic occurrence and species in near-shore macroalgae-feeding marine animals [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2005, 39(16): 5999-6005

[65] Xi S H, Jin Y P, Lv X Q, et al. Distribution and speciation of arsenic by transplacental and early life exposure to inorganic arsenic in offspring rats [J]. Biological Trace Element Research, 2010, 134(1): 84-97

[66] Kenyon E M, Hughes M F, Adair B M, et al. Tissue distribution and urinary excretion of inorganic arsenic and its methylated metabolites in C57BL6 mice following subchronic exposure to arsenate in drinking water [J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2008, 232(3): 448-455

[67] Vahter M. Mechanisms of arsenic biotransformation [J]. Toxicology, 2002, 181-182: 211-217

[68] Newcombe C, Raab A, Williams P N, et al. Accumulation or production of arsenobetaine in humans? [J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2010, 12(4): 832-837

[69] Vahter M. Species differences in the metabolism of arsenic compounds [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 1994, 8(3): 175-182

[70] Vahter M, Marafante E, Dencker L. Metabolism of arsenobetaine in mice, rats and rabbits [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 1983, 30: 197-211

[71] Yamauchi H, Kaise T, Yamamura Y. Metabolism and excretion of orally administered arsenobetaine in the hamster [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 1986, 36(3): 350-355

[72] Kaise T, Watanabe S, Itoh K. The acute toxicity of arsenobetaine [J]. Chemosphere, 1985, 14: 1327-1332

[73] Le X C, Ma M S. Speciation of arsenic compounds by using ion-pair chromatography with atomic spectrometry and mass spectrometry detection [J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 1997, 764(1): 55-64

[74] Choi B S, Choi S J, Kim D W, et al. Effects of repeated seafood consumption on urinary excretion of arsenic species by volunteers [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2010, 58(1): 222-229

[75] Kuehnelt D, Goessler W. Organoarsenic Compounds in the Terrestrial Environment [M]// Craig P J. ed. Organometallic Compounds in the Environment. 2nd ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley, 2003: 223-275

[76] Yoshida K, Inoue Y, Kuroda K, et al. Urinary excretion of arsenic metabolites after long-term oral administration of various arsenic compounds to rats [J]. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part A, 1998, 54(3): 179-192

[77] Yoshida K, Kuroda K, Inoue Y, et al. Metabolites of arsenobetaine in rats: Does decomposition of arsenobetaine occur in mammals? [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 2001, 15: 271-276

[78] Ye Z J, Huang L P, Zhang J C, et al. Biodegradation of arsenobetaine to inorganic arsenic regulated by specific microorganisms and metabolites in mice [J]. Toxicology, 2022, 475: 153238

[79] Harrington C F, Brima E I, Jenkins R O. Biotransformation of arsenobetaine by microorganisms from the human gastrointestinal tract [J]. Chemical Speciation &Bioavailability, 2008, 20(3): 173-180

[80] Chávez-Capilla T, Beshai M, Maher W, et al. Bioaccessibility and degradation of naturally occurring arsenic species from food in the human gastrointestinal tract [J]. Food Chemistry, 2016, 212: 189-197

[81] Hanaoka K, Kaise T, Kai N, et al. Arsenobetaine-decomposing ability of marine microorganisms occurring in particles collected at depths of 1100 and 3500 meters [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 1997, 11: 265-271

[82] Hanaoka K, Yamamoto H, Kawashima K, et al. Ubiquity of arsenobetaine in marine animals and degradation of arsenobetaine by sedimentary micro-organisms [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 1988, 2(4): 371-376

[83] Sanders J G. Microbial role in the demethylation and oxidation of methylated arsenicals in seawater [J]. Chemosphere, 1979, 8(3): 135-137

[84] Hanaoka K, Yamamoto H, Kawashima K, et al. Ubiquity of arsenobetaine in marine animals and degradation of arsenobetaine by sedimentary micro-organisms [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 1988, 2(4): 371-376

[85] Khokiattiwong S, Goessler W, Pedersen S N, et al. Dimethylarsinoylacetate from microbial demethylation of arsenobetaine in seawater [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 2001, 15(6): 481-489

[86] Lehr C R, Polishchuk E, Radoja U, et al. Demethylation of methylarsenic species by Mycobacterium neoaurum [J]. Applied Organometallic Chemistry, 2003, 17(11): 831-834

[87] Huang J H, Scherr F, Matzner E. Demethylation of dimethylarsinic acid and arsenobetaine in different organic soils [J]. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 2007, 182(1): 31-41

[88] Kann S, Estes C, Reichard J F, et al. Butylhydroquinone protects cells genetically deficient in glutathione biosynthesis from arsenite-induced apoptosis without significantly changing their prooxidant status [J]. Toxicological Sciences: An Official Journal of the Society of Toxicology, 2005, 87(2): 365-384

[89] Engström K, Vahter M, Mlakar S, et al. Polymorphisms in arsenic(+Ⅲ oxidation state) methyltransferase (AS3MT) predict gene expression of AS3MT as well as arsenic metabolism [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2010, 119: 182-188

[90] Zhu Y G, Xue X M, Kappler A, et al. Linking genes to microbial biogeochemical cycling: Lessons from arsenic [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2017, 51(13): 7326-7339