有机紫外吸收剂(organic ultraviolet absorbers, OUVs)是一类能够吸收长波紫外线(ultraviolet-A, UVA)(320~400 nm)和中波紫外线(ultraviolet-B, UVB)(280~320 nm)的有机化合物,包含有机紫外线过滤剂(organic ultraviolet filter, OUVF)和有机紫外线稳定剂(organic ultraviolet stabilizer, OUVS)[1],前者主要添加于防晒霜,用于屏蔽紫外线照射对人体的危害;后者主要添加于工业产品,例如塑料、油漆、纺织品及家具等,用于防止物品受到紫外线损害老化[2]。OUVs通过海上娱乐活动(如游泳、冲浪等)[3]、地下水径流、废水排放[4]和大气沉降[5]等多种方式进入海洋,沿着食物链传播,重新分配于海洋生态系统的不同营养级。目前,OUVs已经在海豚[6]、乌贼[7]、珊瑚[8]和贻贝[9]等多种海洋生物中检测到。和淡水生物相比,海洋生物生长在高盐、碱性及风浪较大的海洋环境,OUVs对其内分泌干扰[10],神经[11]、基因[12]及生长发育[13]毒性危害可能有别于淡水生物。例如,先前的研究表明盐度会增大3-(4-甲基苄烯)-樟脑(4-methylbenzylidene camphor, 4-MBC)对虎斑猛水蚤(copepod Tigriopus)的慢性毒性[14]。另外,在海洋生态风险评价中,为了保守评估污染物对海洋生物的毒性,评估因子(assessment factor, AF)的选择比淡水生物高一个数量级[15]。

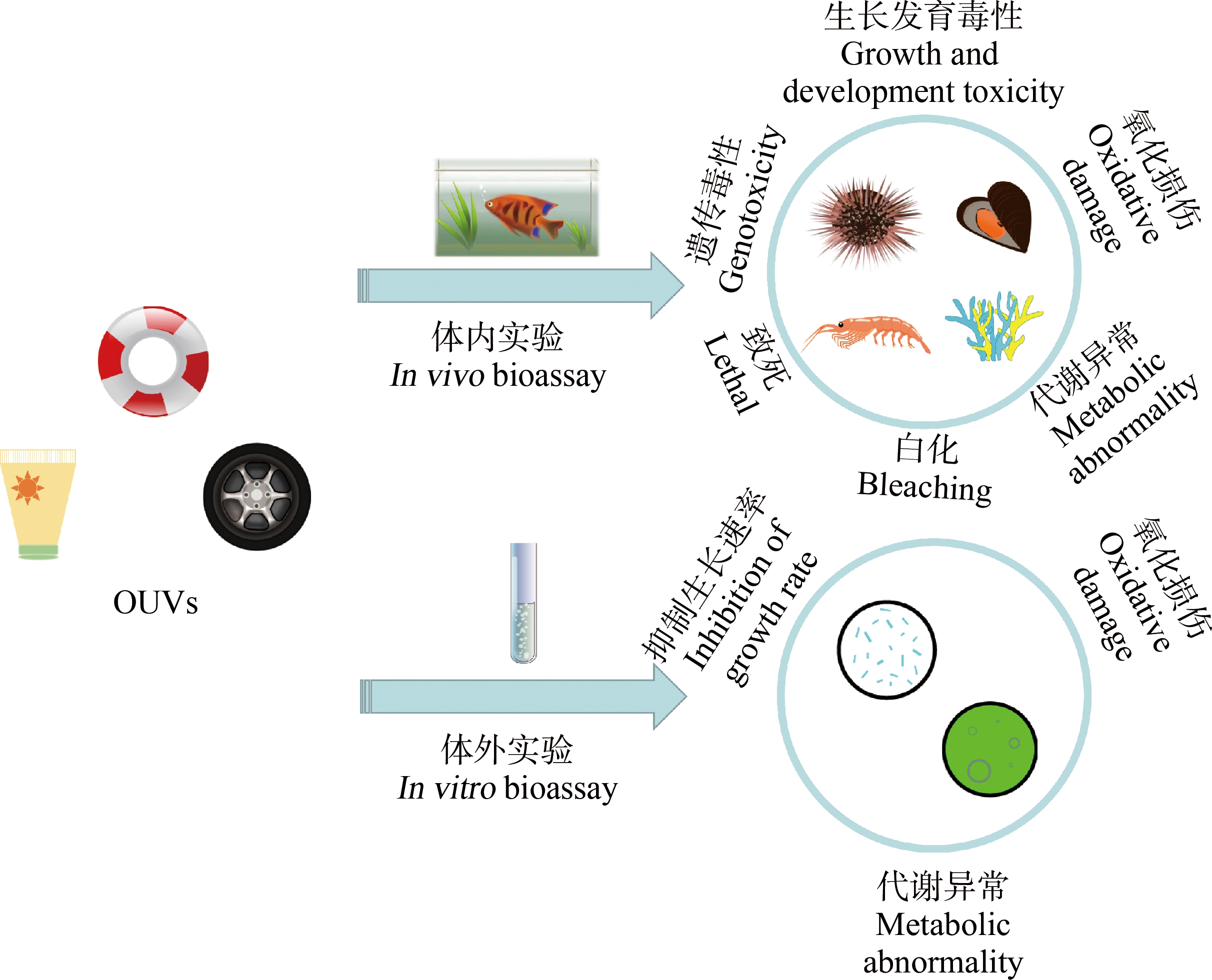

目前,我国国内针对OUVs对海洋生态环境影响的综述仅有2篇,其中一篇“防晒剂的海洋环境行为与生物毒性”侧重于阐明防晒剂在海洋中的迁移、转化和挥发等环境行为,并按照紫外吸收剂种类介绍了它们对海洋生物的毒性效应[16];另一篇“防晒剂对海洋生态环境的污染及潜在影响”侧重于介绍紫外吸收剂在海洋中的污染现状及宏观上对海洋生态的潜在影响[17]。国外3篇关于海洋OUVs的综述主要是按照OUV种类分别介绍了其在海洋生物中的富集及毒理效应[18-20]。本文按照体内和体外的毒理实验划分,从不同效应终点系统分析了OUVs对海洋生物的危害(图1)。一般,体内毒性实验是对整体动植物所进行的毒性、毒理实验,涉及到动物的实验往往需要考虑动物伦理问题;而体外毒性实验是指利用离体的器官、培养的组织切片或者细胞,在体外进行的毒理试验[21]。然而,关于微藻和细菌毒理实验的划分,目前没有统一的标准。部分学者认为细菌和微藻作为独立的生物体,以其为受试生物开展的毒理实验应归为体内毒理实验[22-23];而另外一些学者认为细菌和微藻毒理实验具有体外生物测试的特征,例如受试生物易于培养、操作简单和实验周期短等,故将其划分为体外毒理实验[24-27]。本综述中,我们采用Huang等[28]在Science of the Total Environment期刊上发表的综述划分方式,将在细菌和微藻上开展的毒理实验划分为体外毒理实验。本综述参考文献搜索条件如下:主题marine;标题ultraviolet absorbent or UV filter or ultraviolet filter or sunscreen or UV stabilizer or UV-absorbing or UV chemicals or UV-filter;年份2006—2021。期刊主要为Journal of Chromatography A、Science of the Total Environment、Environmental Science &Technology、Talanta、Chemosphere、Environmental Pollution等环境科学或分析化学相关的自然科学期刊。由于本综述重点是归纳分析OUVs对海洋生物的毒理效应,故无机紫外吸收剂[29-32]不做重点介绍。

图1 OUVs对海洋生物的毒理概览

注:OUVs表示有机紫吸收剂。

Fig. 1 Overview of the toxicity of OUVs on marine organisms

Note: OUVs means organic ultraviolet absorbers.

1 OUVs在海洋生物体内的毒理效应(In vivo toxicological effects of OUVs on marine organisms)

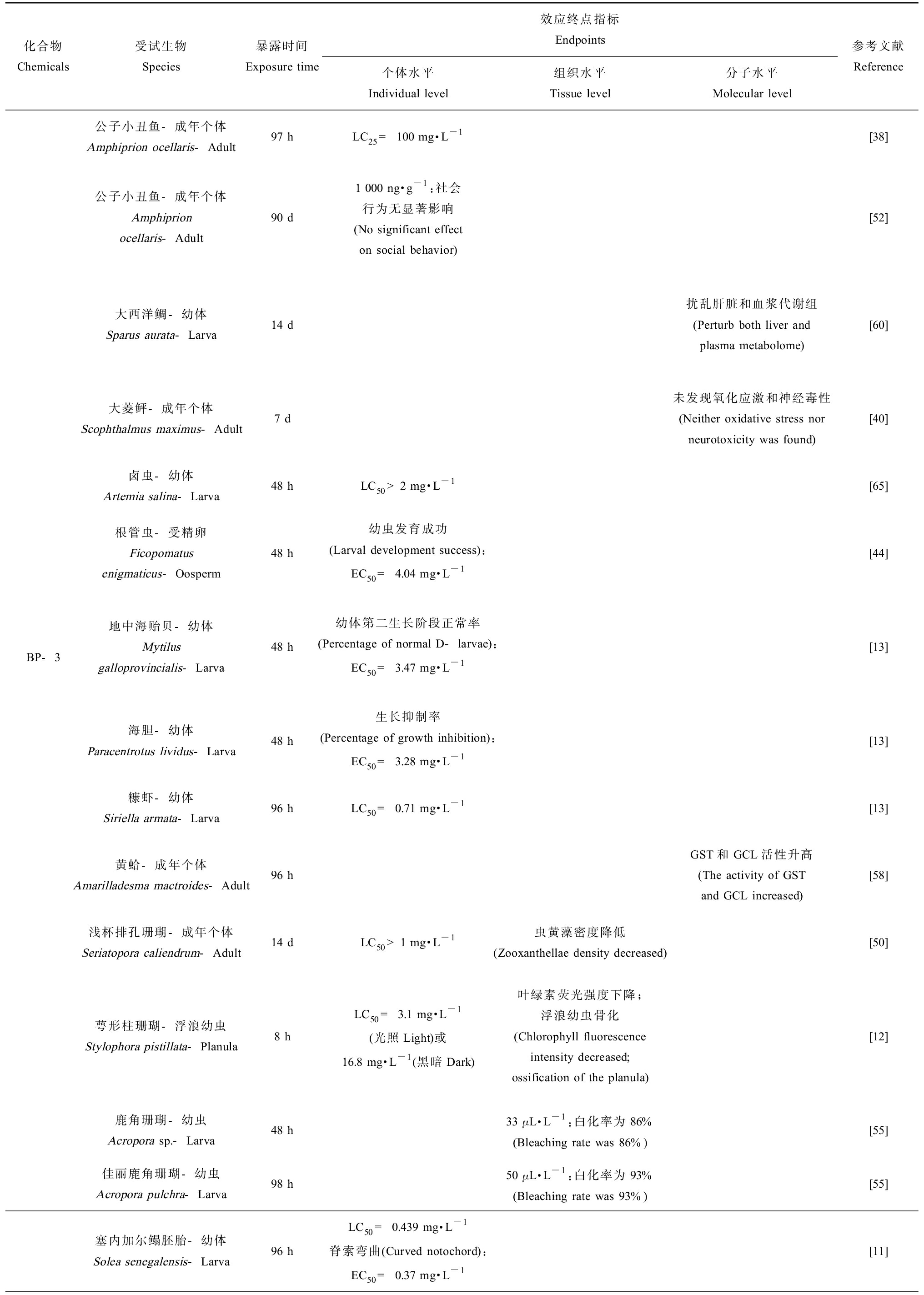

相比于淡水生物,海洋生物受样本获取困难、培养条件苛刻等限制,毒理实验的开展较为困难。目前,海洋受试生物包括鱼类、贝类、甲壳类、棘皮类、珊瑚、细菌和藻类等。虽然OUVs在多种淡水鱼(斑马鱼[33]、青鳉鱼[34]、五彩搏鱼[35]、虹鳟鱼[36]和鲫鱼[37]等)上开展过毒理实验,但是海洋鱼类局限于小丑鱼[38]、塞内加尔鳎[11]、大西洋鲷[39]和大菱鲆[40]4种。OUVs种类包括二苯甲酮-3(benzophenone-3, BP-3)、4-MBC、奥克立林(octocrylene, OC)、对甲氧基肉桂酸辛酯(ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate, EHMC)、对-N,N-二甲氨基苯甲酸异辛酯(2-ethylhexyl 4-(dimethylamino) benzoate, OD-PABA)、胡莫柳酯(homosolate, HS)和阿伏苯宗(avobenzone, AVO)等。多项研究均已表明,在体内毒理实验中,OUVs在个体、组织、分子等层面均会对海洋生物产生危害(表1)。

表1 OUVs在海洋生物体内的毒理效应

Table 1 In vivo toxicological effects of OUVs on marine organisms

化合物Chemicals受试生物Species暴露时间Exposure time效应终点指标Endpoints个体水平Individual level组织水平Tissue level分子水平Molecular level参考文献Reference公子小丑鱼-成年个体Amphiprion ocellaris-Adult97 hLC25 = 100 mg·L-1[38]公子小丑鱼-成年个体Amphiprion ocellaris-Adult90 d1 000 ng·g-1:社会行为无显著影响(No significant effect on social behavior)[52]大西洋鲷-幼体Sparus aurata-Larva14 d扰乱肝脏和血浆代谢组(Perturb both liver and plasma metabolome)[60]大菱鲆-成年个体Scophthalmus maximus-Adult7 d未发现氧化应激和神经毒性(Neither oxidative stress nor neurotoxicity was found)[40]卤虫-幼体Artemia salina-Larva48 hLC50>2 mg·L-1[65]根管虫-受精卵Ficopomatus enigmaticus-Oosperm48 h幼虫发育成功(Larval development success):EC50 = 4.04 mg·L-1[44]BP-3地中海贻贝-幼体Mytilus galloprovincialis-Larva48 h幼体第二生长阶段正常率(Percentage of normal D-larvae):EC50 = 3.47 mg·L-1[13]海胆-幼体Paracentrotus lividus-Larva48 h生长抑制率(Percentage of growth inhibition):EC50 = 3.28 mg·L-1[13]糠虾-幼体Siriella armata-Larva96 hLC50 = 0.71 mg·L-1[13]黄蛤-成年个体Amarilladesma mactroides-Adult96 hGST和GCL活性升高 (The activity of GST and GCL increased)[58]浅杯排孔珊瑚-成年个体Seriatopora caliendrum-Adult14 dLC50>1 mg·L-1虫黄藻密度降低(Zooxanthellae density decreased)[50]萼形柱珊瑚-浮浪幼虫Stylophora pistillata-Planula8 hLC50 = 3.1 mg·L-1(光照Light)或16.8 mg·L-1(黑暗Dark)叶绿素荧光强度下降;浮浪幼虫骨化(Chlorophyll fluorescence intensity decreased; ossification of the planula)[12]鹿角珊瑚-幼虫Acropora sp.-Larva48 h33 μL·L-1:白化率为86% (Bleaching rate was 86%)[55]佳丽鹿角珊瑚-幼虫Acropora pulchra-Larva98 h50 μL·L-1:白化率为93% (Bleaching rate was 93%)[55]塞内加尔鳎胚胎-幼体Solea senegalensis-Larva96 hLC50 = 0.439 mg·L-1脊索弯曲(Curved notochord):EC50 = 0.37 mg·L-1[11]

续表1化合物Chemicals受试生物Species暴露时间Exposure time效应终点指标Endpoints个体水平Individual level组织水平Tissue level分子水平Molecular level参考文献Reference海胆-幼体Paracentrotus lividus-Larva48 h生长抑制率(Percentage of growth inhibition):EC50 = 0.85 mg·L-1[13]根管虫-受精卵Ficopomatus enigmaticus- Oosperm48 h幼虫发育成功(Larval development success):EC50 = 0.84 mg·L-1[44]4-MBC地中海贻贝-幼体Mytilus galloprovincialis-Larva48 h幼体第二生长阶段正常率(Percentage of normal D-larvae):EC50 = 0.59 mg·L-1[13]糠虾-幼体Siriella armata-Larva96 hLC50 = 0.19 mg·L-1[13]菲律宾蛤仔-成年个体Ruditapes philippinarum-Adult168 hLC50 = 7.71 μg·L-1GST基因表达量增加(Expression of the gene encoding GST increased)[15]鹿角珊瑚-幼虫Acropora sp.-Larva48 h33 μL·L-1:白化率为63% (Bleaching rate was 63%)[55]佳丽鹿角珊瑚-幼虫Acropora pulchra-Larva62 h50 μL·L-1:白化率为95% (Bleaching rate was 95%)[55]根管虫-成年个体Ficopomatus enigmaticus-Adult28 dGST活性升高;AChE活性下降;LPO水平上升 (GST activity increased; AchE activity decreased; LPO level increased)[59]地中海贻贝-幼体Mytilus galloprovincialis-Larva48 h幼体第二生长阶段正常率(Percentage of normal D-larvae):EC50 = 3.11 mg·L-1[13]EHMC根管虫-受精卵Ficopomatus enigmaticus- Oosperm48 h幼虫发育成功(Larval development success):EC50 = 2.81 mg·L-1[44]海胆-幼体Paracentrotus lividus-Larva48 h生长抑制率(Percentage of growth inhibition):EC50 = 0.28 mg·L-1[13]糠虾-幼体Siriella armata-Larva96 hLC50 = 0.20 mg·L-1[13]鹿角珊瑚-幼虫Acropora sp.-Larva24 h33 μL·L-1:白化率为91% (Bleaching rate was 91%)[55]佳丽鹿角珊瑚-幼虫Acropora pulchra-Larva96 h50 μL·L-1:白化率为91% (Bleaching rate was 91%)[55]根管虫-受精卵Ficopomatus enigmaticus- Oosperm48 h幼虫发育成功(Larval development success):EC50 = 14.74 mg·L-1[44]

续表1化合物Chemicals受试生物Species暴露时间Exposure time效应终点指标Endpoints个体水平Individual level组织水平Tissue level分子水平Molecular level参考文献Reference海胆-幼体Paracentrotus lividus-Larva48 h生长抑制率(Percentage of growth inhibition):EC50 = 0.74 mg·L-1[43]OC地中海贻贝-幼体Mytilus galloprovincialis-Larva48 h幼体第二生长阶段正常率(Percentage of normal D-larvae):EC50>0.65 mg·L-1[43]卤虫-幼体Artemia salina-Larva48 hLC50 = 0.61 mg·L-1[65]紫贻贝-成年个体Mytilus edulis-Adult14 d溶酶体膜完整性下降(Lysosomal membrane integrity decreased)ROS产生增加 (ROS production increased)[10]鹿角杯型珊瑚-成年个体Pocillopora damicornis-Adult168 h形成脂肪酸络合物(Forming OC-fatty acid conjugates) [61]OD-PABA海胆-幼体Paracentrotus lividus-Larva48 h生长抑制率(Percentage of growth inhibition):EC50 = 0.28 mg·L-1[43]地中海贻贝-幼体Mytilus galloprovincialis-Larva48 h幼体第二生长阶段正常率(Percentage of normal D-larvae):EC50 = 0.13 mg·L-1[43]AVO根管虫-受精卵Ficopomatus enigmaticus- Oosperm48 h幼虫发育成功(Larval development success):EC50 = 9.89 mg·L-1[44]卤虫-幼体Artemia salina-Larva48 hLC50 = 1.84 mg·L-1[65]HS卤虫-幼体Artemia salina-Larva48 hLC50 = 2.36 mg·L-1[65]PBS紫贻贝-成年个体Mytilus edulis-Adult14 d溶酶体膜完整性下降(Lysosomal membrane integrity decreased)ROS产生增加,硫代巴比妥酸反应物和蛋白羰基水平升高(ROS production increased, and the levels of the thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances and protein carbonyls increased)[10]ES鹿角杯型珊瑚-成年个体Pocillopora damicornis-Adult7 d不饱和脂肪酸、溶血磷脂酰胆碱和溶血磷脂酰乙醇胺浓度显著升高 (The significant increases in the concentrations of polyunsaturated fatty acids, lysophosphatidylcholines and lysophosphatidylethanolamines)[62]UV-327紫色球海胆-幼体StrongylocentrotusPurpuratus-Larva4 d抑制生长(Inhibition of growth)[48]

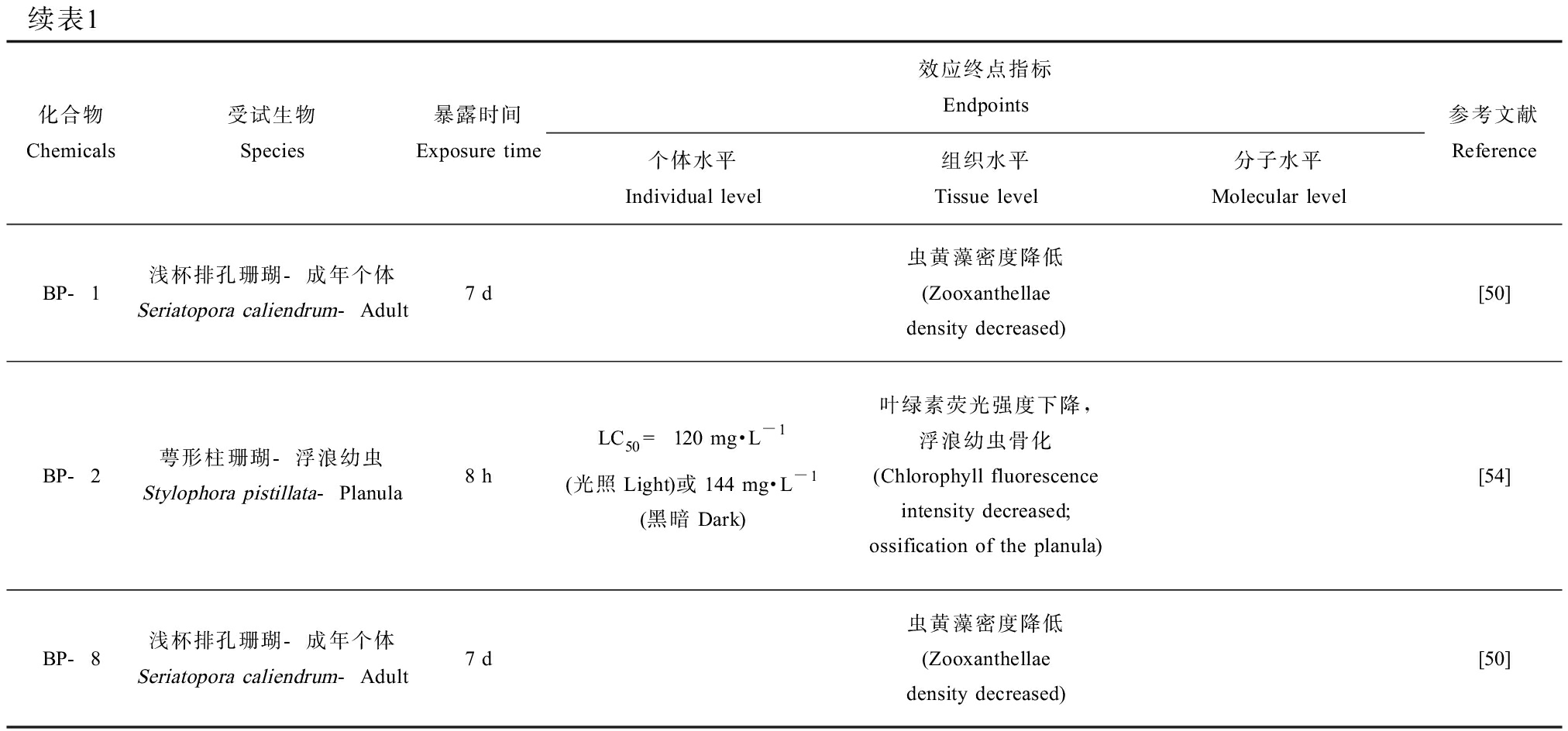

续表1化合物Chemicals受试生物Species暴露时间Exposure time效应终点指标Endpoints个体水平Individual level组织水平Tissue level分子水平Molecular level参考文献ReferenceBP-1浅杯排孔珊瑚-成年个体Seriatopora caliendrum-Adult7 d虫黄藻密度降低(Zooxanthellae density decreased)[50]BP-2萼形柱珊瑚-浮浪幼虫Stylophora pistillata-Planula8 hLC50 = 120 mg·L-1(光照Light)或144 mg·L-1(黑暗Dark)叶绿素荧光强度下降,浮浪幼虫骨化(Chlorophyll fluorescence intensity decreased; ossification of the planula)[54]BP-8浅杯排孔珊瑚-成年个体Seriatopora caliendrum-Adult7 d虫黄藻密度降低(Zooxanthellae density decreased)[50]

注:BP-3、4-MBC、EHMC、OC、OD-PABA、AVO、HS、PBS、ES、UV-327、BP-1、BP-2和BP-8分别为二苯甲酮-3、3-(4-甲基苄烯)-樟脑、对甲氧基肉桂酸辛酯、奥克立林、对-N,N-二甲氨基苯甲酸异辛酯、阿伏苯宗、胡莫柳酯、苯基苯并咪唑磺酸、水杨酸异辛酯、2-(2’-羟基-3’,5’-二特丁基苯基)-5-氯苯并三唑、二苯甲酮-1、二苯甲酮-2和二苯甲酮-8;LC50为半数致死浓度;EC50为半数效应浓度;GST为谷胱甘肽-S-转移酶;GCL为谷氨酰半胱氨酸连接酶;AChE为乙酰胆碱酯酶;LPO为过氧化脂质;ROS为活性氧。

Note: BP-3, 4-MBC, EHMC, OC, OD-PABA, AVO, HS, PBS, ES, UV-327, BP-1, BP-2 and BP-8 are the abbreviations of benzophenone-3, 4-methylbenzylidene camphor, ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate, octocrylene, 2-ethylhexyl 4-(dimethylamino) benzoate, avobenzone, homosolate, ensulizole, ethylhexyl salicylate, 2,4-di-t-butyl-6-(5-chloro-2H-benzotriazole-2-yl) phenol, benzophenone-1, benzophenone-2 and benzophenone-8, respectively; LC50 means median lethal concentrations; EC50 means median effect concentrations; GST means glutathione-S-transferase; GCL means glutamate cysteine ligase; AChE means acetylcholinesterase; LPO means lipid peroxide; ROS means reactive oxygen species.

1.1 在个体水平上的毒性

在个体水平上,OUVs对海洋生物的毒性表现为致死、抑制生长发育、影响幼虫附着及社会行为等。OUVs对海洋生物的致死危害程度和生物种类、生长阶段及脂肪含量有关。成年公子小丑鱼(Amphiprion ocellaris)暴露于100 mg·L-1的BP-3溶液97 h,其死亡率为25%[38];而青鳉鱼(Oryzias latipes)幼体暴露于BP-3溶液96 h,其半数致死浓度(median lethal concentrations, LC50)为0.935 mg·L-1[41]。幼体生物生长发育较快、新陈代谢旺盛,而器官发育不成熟导致其对毒物的解毒能力较差[42]。OUVs对海洋生物生长发育的毒性和OUV种类及生物种类有关。例如,OD-PABA、4-MBC、OC、EHMC和BP-3对地中海贻贝(Mytilus galloprovincialis)幼体生长发育的影响依次降低;而对海胆(Paracentrotus lividus)生长发育影响顺序为:OD-PABA>EHMC>OC>4-MBC>BP-3[13, 43];对根管虫影响的顺序为:4-MBC>EHMC>BP-3>OC[44]。其中,OUVs对海胆毒性的影响程度顺序和对淡水大型蚤(Daphnia magna)一致[45]。在这5种OUVs中,BP-3在4种动物模型中均表现出较弱的毒性,这可能和BP-3的高熔点及较低的亲脂性(logKow=3.52)有关。相关研究表明,毒物的疏水性和熔点会影响其毒性。亲脂性越低,其毒性越低;熔点越高,其基线毒性越弱[46]。生物的脂肪含量也会影响亲脂性毒物对其毒性。例如,4-MBC在96 h内对塞内加尔鳎(Solea senegalensis)(海鱼)鱼卵致死的LC50为0.439 mg·L-1[11],而相同条件下对斑马鱼(Danio rerio)(淡水鱼)胚胎致死的LC50为2.4 mg·L-1[47]。推测这是因为塞内加尔鳎鱼卵含有更高的卵黄囊脂,从而富集OUVs的能力更强[11]。值得注意的是,OUVs对海洋生物生长发育的抑制作用并非呈现绝对的剂量-效应正相关性。当紫色球海胆(Strongylocentrotus purpuratus)幼虫暴露于0.5 mg·L-1的 2-(2’-羟基-3’,5’-二特丁基苯基)-5-氯苯并三唑(2,4-di-t-butyl-6-(5-chloro-2H-benzotriazole-2-yl) phenol, UV-327)溶液时,其生长发育受抑制程度最高;而当UV-327浓度高于或低于0.5 mg·L-1时,其抑制作用均发生下降[48]。

在幼虫附着和社会行为影响上,OUVs的相关毒理实验研究较少,现有研究分别是基于珊瑚和小丑鱼作为受试生物。珊瑚是由珊瑚虫、共生虫黄藻和微生物等构成的共生体,其幼虫的生长繁殖需要附着于固体基质[49],当受到环境胁迫时,幼虫附着率降低。相关研究表明二苯甲酮类OUVs对珊瑚附着率的影响因物质种类而异[50]。在社会行为(社会行为是指生物体在种群中的生活行为活动,包括利益冲突、繁殖冲突和从属关系等[51])上,1 000 ng·g-1的BP-3饲食对公子小丑鱼无显著影响[52]。

1.2 在组织水平上的毒性

从组织水平上研究OUVs对海洋生物的毒理效应,目前仅在紫贻贝(Mytilus edulis)和珊瑚上开展,主要表现在破坏紫贻贝血细胞溶酶体膜结构或诱导珊瑚发生白化。当紫贻贝暴露在10 μg·L-1的苯基苯并咪唑磺酸(ensulizole, PBS)或OC溶液14 d时,其细胞发生氧化应激反应,具体表现为血细胞溶酶体膜破损及组织蛋白酶-D(cathepsin D)活性降低[10]。珊瑚白化(图2(b))是一种珊瑚因失去体内共生虫黄藻或共生虫黄藻失去体内色素而变白的一种生态现象[53]。当浅杯排孔珊瑚(Seriatopora caliendrum)暴露于1 000 μg·L-1的二苯甲酮-1(benzophenone-1, BP-1)、BP-3、二苯甲酮-8(benzophenone-8, BP-8)溶液7 d时,其体内共生虫黄藻密度下降,指示珊瑚发生了白化[50];当萼形柱珊瑚(Stylophora pistillata)浮浪幼虫暴露于2 460 μg·L-1的二苯甲酮-2(benzophenone-2, BP-2)溶液中8 h时,其体内叶绿素荧光强度下降,同样指示珊瑚发生了白化[54]。OUVs可能通过病毒感染诱导虫黄藻细胞裂解[55]、或通过破坏虫黄藻体内的氧化应激系统、或珊瑚宿主调控的虫黄藻降解机制[12]等途径诱导珊瑚发生白化。

1.3 在分子水平上的毒性

在分子水平上,OUVs会造成海洋生物遗传物质受损、酶活性改变及小分子代谢异常等,即在基因、蛋白和代谢物等方面均产生危害[56]。当生物体在受到生物或者环境胁迫时,机体会通过调控氧化应激系统来减小损伤[57]。例如,当黄蛤(Amarilladesma mactroides)暴露于1 μg·L-1的BP-3溶液96 h,其体内谷胱甘肽-S-转移酶(glutathione-S-transferase, GST)和谷氨酰半胱氨酸连接酶(glutamate cysteine ligase, GCL)的活性上升[58];当菲律宾蛤仔(Ruditapes philippinarum)暴露于1.34 μg·L-1的4-MBC溶液7 d,其体内GST基因、B细胞淋巴瘤-2(B-cell lymphoma-2, BCL-2)基因等多种基因表达上调[15];当根管虫暴露于EHMC溶液时,其体内GST活性和过氧化脂质(lipid peroxide, LPO)含量上升,而乙酰胆碱酯酶(acetylcholinesterase, AChE)活性下降[59]。生物体内代谢小分子的异常会引起代谢紊乱,进而影响生物体功能。例如,当大西洋鲷(Sparus aurata)暴露于50 mg·L-1的BP-3溶液14 d时,其体内脂质、苯乙酰甘氨酸、马尿酸等代谢均发生紊乱[60];当鹿角杯型珊瑚(Pocillopora damicornis)暴露于>50 μg·L-1的OC溶液7 d时,其体内酰基肉毒碱含量上升,线粒体功能紊乱[61];而水杨酸异辛酯(ethylhexyl salicylate, ES)同样会引起该种珊瑚体内不饱和脂肪酸、溶血磷脂酰胆碱和溶血磷脂酰乙醇胺含量的上调[62]。OUVs对海鱼及淡水鱼的分子毒性具有差异。例如,3 μg·g-1的BP-3对大菱鲆无神经毒性,而200 μg·L-1的BP-3会影响淡水鲫鱼(Carassius auratus)体内的AChE活性,损伤其神经系统[63]。OUVs和其他污染物联合作用可能会加剧对海洋生物的分子毒性。例如BP-3和微塑料(microplastics, MPs)联合暴露会增强蛤蜊(Scrobicularia plana)体内活性氧(reactive oxygen species, ROS)的含量,造成谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶(glutathione peroxidase, GPx)活性上升及DNA损伤[64];而BP-3和纳米二氧化钛(titanium dioxide nanoparticles, nano-TiO2)联合暴露会同样激活大菱鲆(Scophthalmus maximus)体内的抗氧化系统[40]。

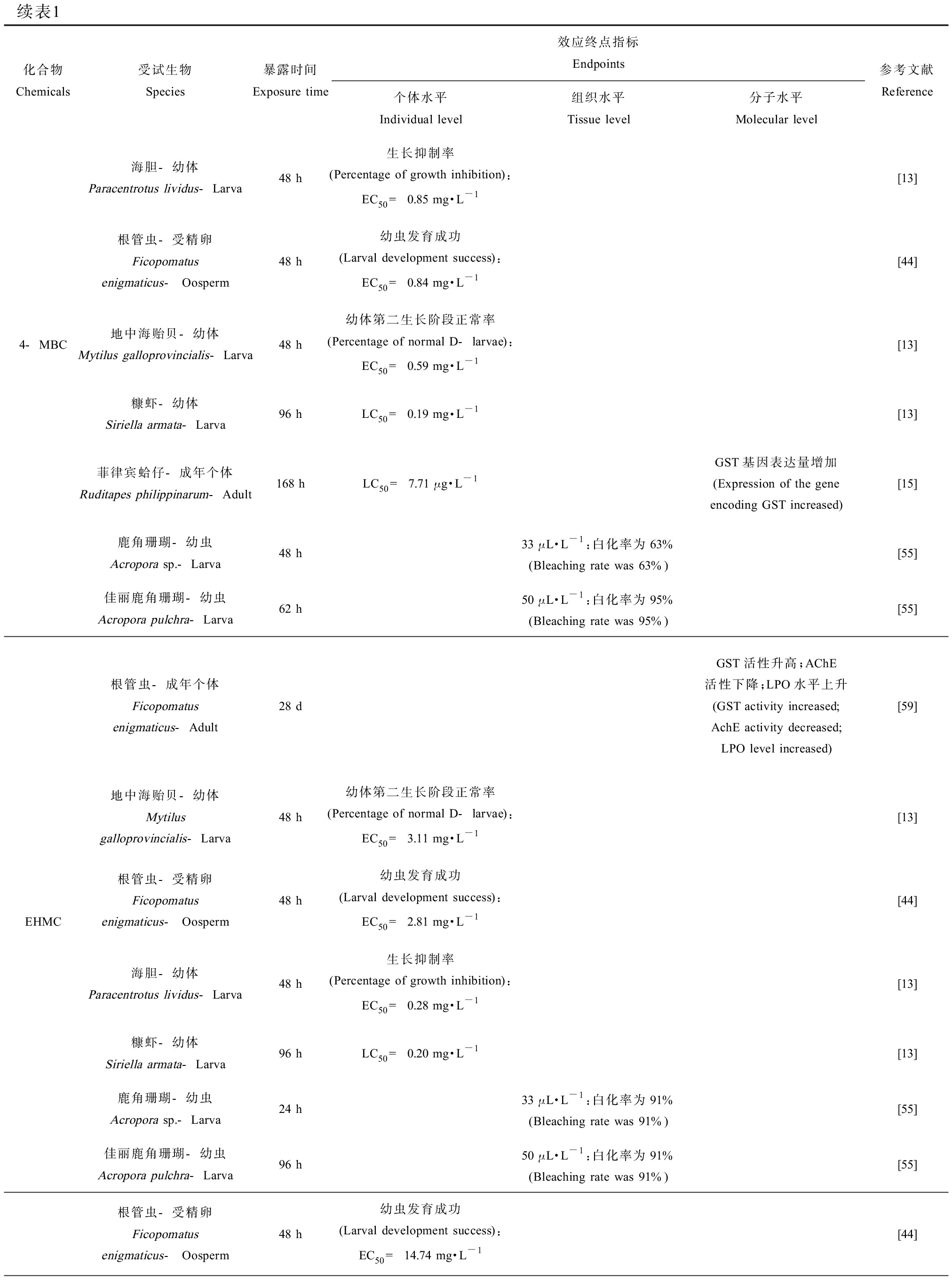

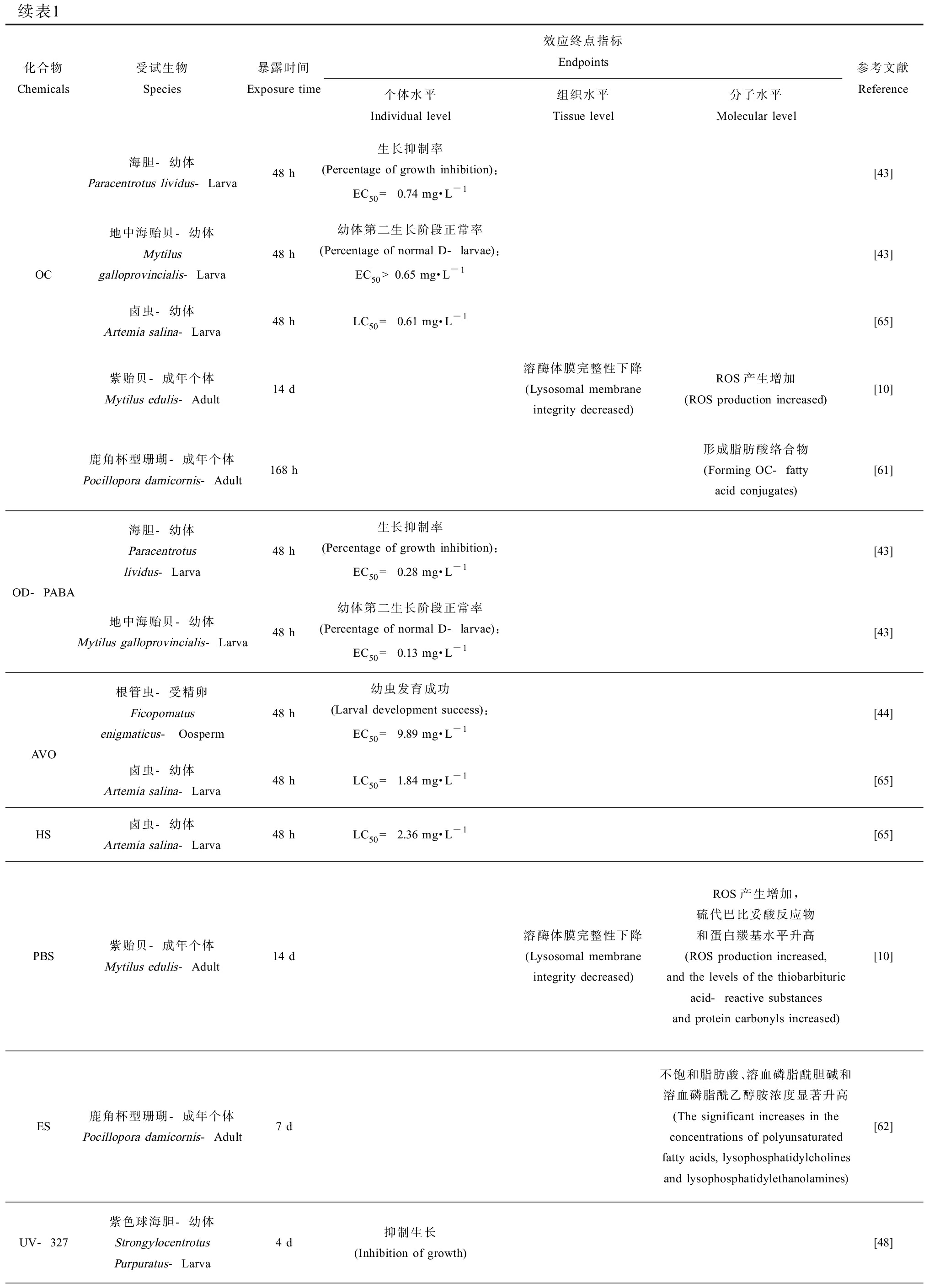

2 OUVs在海洋生物体外的毒理效应(In vitro toxicological effects of OUVs on marine organisms)

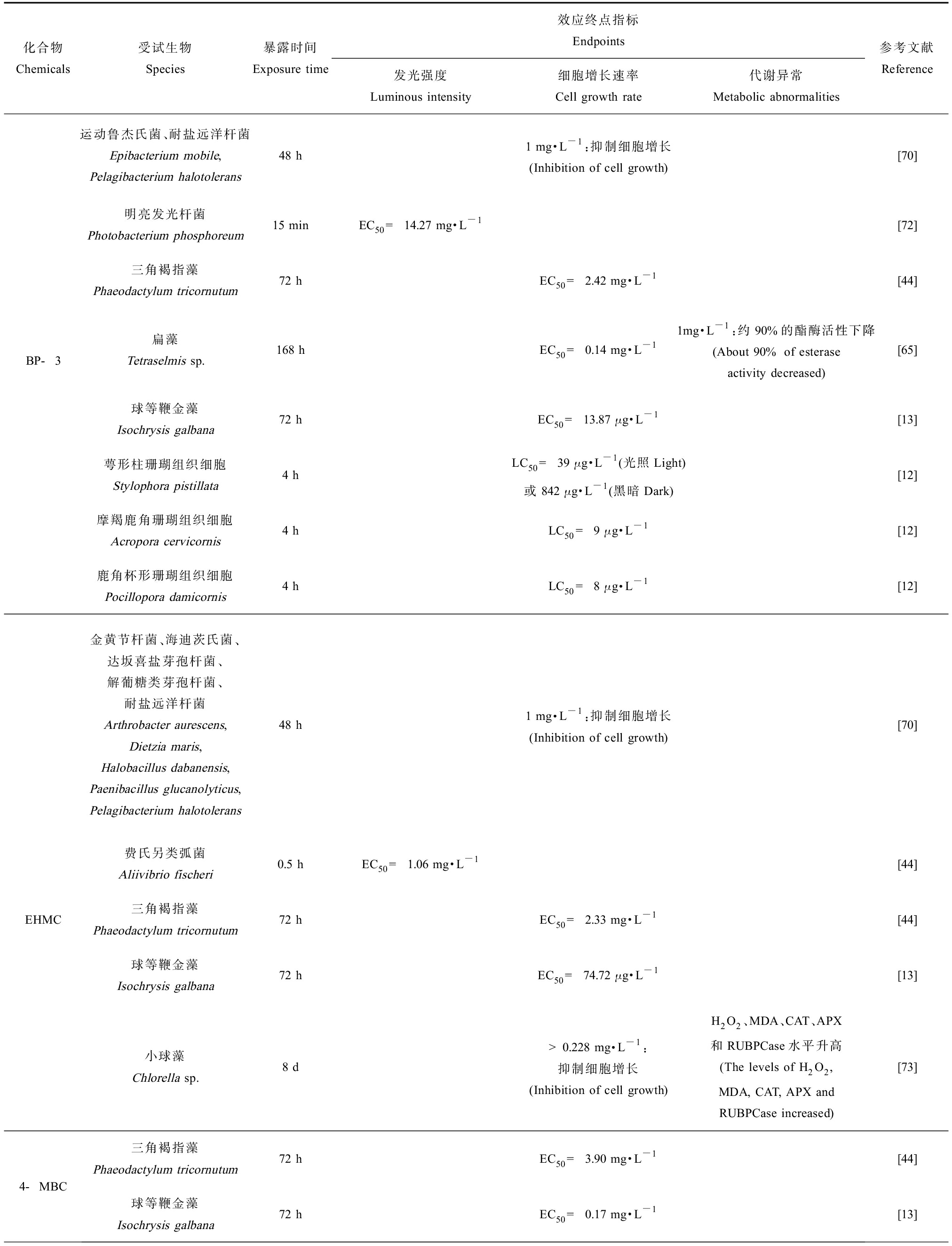

细菌、微藻和组织离体细胞是海洋生物体外毒理实验常用的3类受试体(表2)。藻类处于海洋生态系统营养级的最底层,其主要作用为捕获营养物质并促进其循环利用[65-66],并提供丰富的生物量[67],在整个海洋生态系统物质循环、能量流动以及提高生物多样性中具有重要作用。而海洋细菌作为海洋生态系统中的分解者与生产者,当海洋生态系统的动态平衡遭受某种破坏时,海洋细菌以其敏感的适应能力和极快的繁殖速度,迅速形成异常微生物区系,积极参与氧化、还原活动,调整和促进新动态平衡的形成和发展[68],在海洋生态系统中同样发挥着举足轻重的作用。和体内生物毒理实验相比,体外毒理实验具有能够在细胞水平上观察毒性的优势[69]。通常,毒理学实验选择处于生长对数期的藻类、细菌或组织离体细胞,这是因为处于该生长阶段的微生物或离体细胞生长速率较快,能够高灵敏度地反映化合物的毒性大小。例如,处于生长对数期的金黄节杆菌(Arthrobacter aurescens)、海迪茨氏菌(Dietzia maris)和食鸟氨酸噬冷菌(Algoriphagus ornithinivorans)等表现出对BP-3、EHMC、OC、4-MBC或HS其中一种或多种物质的敏感,而处于稳定期的细菌基本不受这些OUVs的影响[70]。

表2 OUVs在海洋生物体外的毒理效应

Table 2 In vitro toxicological effects of OUVs on marine organisms

化合物Chemicals受试生物Species暴露时间Exposure time效应终点指标Endpoints发光强度Luminous intensity细胞增长速率Cell growth rate代谢异常Metabolic abnormalities参考文献Reference运动鲁杰氏菌、耐盐远洋杆菌Epibacterium mobile, Pelagibacterium halotolerans48 h1 mg·L-1:抑制细胞增长(Inhibition of cell growth)[70]明亮发光杆菌Photobacterium phosphoreum15 minEC50 = 14.27 mg·L-1[72]三角褐指藻Phaeodactylum tricornutum72 hEC50 = 2.42 mg·L-1[44]BP-3扁藻Tetraselmis sp.168 hEC50 = 0.14 mg·L-11mg·L-1:约90%的酯酶活性下降(About 90% of esterase activity decreased)[65]球等鞭金藻Isochrysis galbana72 hEC50 = 13.87 μg·L-1[13]萼形柱珊瑚组织细胞Stylophora pistillata4 hLC50 = 39 μg·L-1(光照Light)或842 μg·L-1(黑暗Dark)[12]摩羯鹿角珊瑚组织细胞Acropora cervicornis4 hLC50 = 9 μg·L-1[12]鹿角杯形珊瑚组织细胞Pocillopora damicornis4 hLC50 = 8 μg·L-1[12]金黄节杆菌、海迪茨氏菌、达坂喜盐芽孢杆菌、解葡糖类芽孢杆菌、耐盐远洋杆菌Arthrobacter aurescens, Dietzia maris, Halobacillus dabanensis, Paenibacillus glucanolyticus, Pelagibacterium halotolerans48 h1 mg·L-1:抑制细胞增长(Inhibition of cell growth)[70]费氏另类弧菌Aliivibrio fischeri0.5 hEC50 = 1.06 mg·L-1[44]EHMC三角褐指藻Phaeodactylum tricornutum72 hEC50 = 2.33 mg·L-1[44]球等鞭金藻 Isochrysis galbana72 hEC50 = 74.72 μg·L-1[13]小球藻 Chlorella sp.8 d>0.228 mg·L-1:抑制细胞增长(Inhibition of cell growth)H2O2、MDA、CAT、APX和RUBPCase水平升高(The levels of H2O2, MDA, CAT, APX and RUBPCase increased)[73]4-MBC三角褐指藻Phaeodactylum tricornutum72 hEC50 = 3.90 mg·L-1[44]球等鞭金藻Isochrysis galbana72 hEC50 = 0.17 mg·L-1[13]

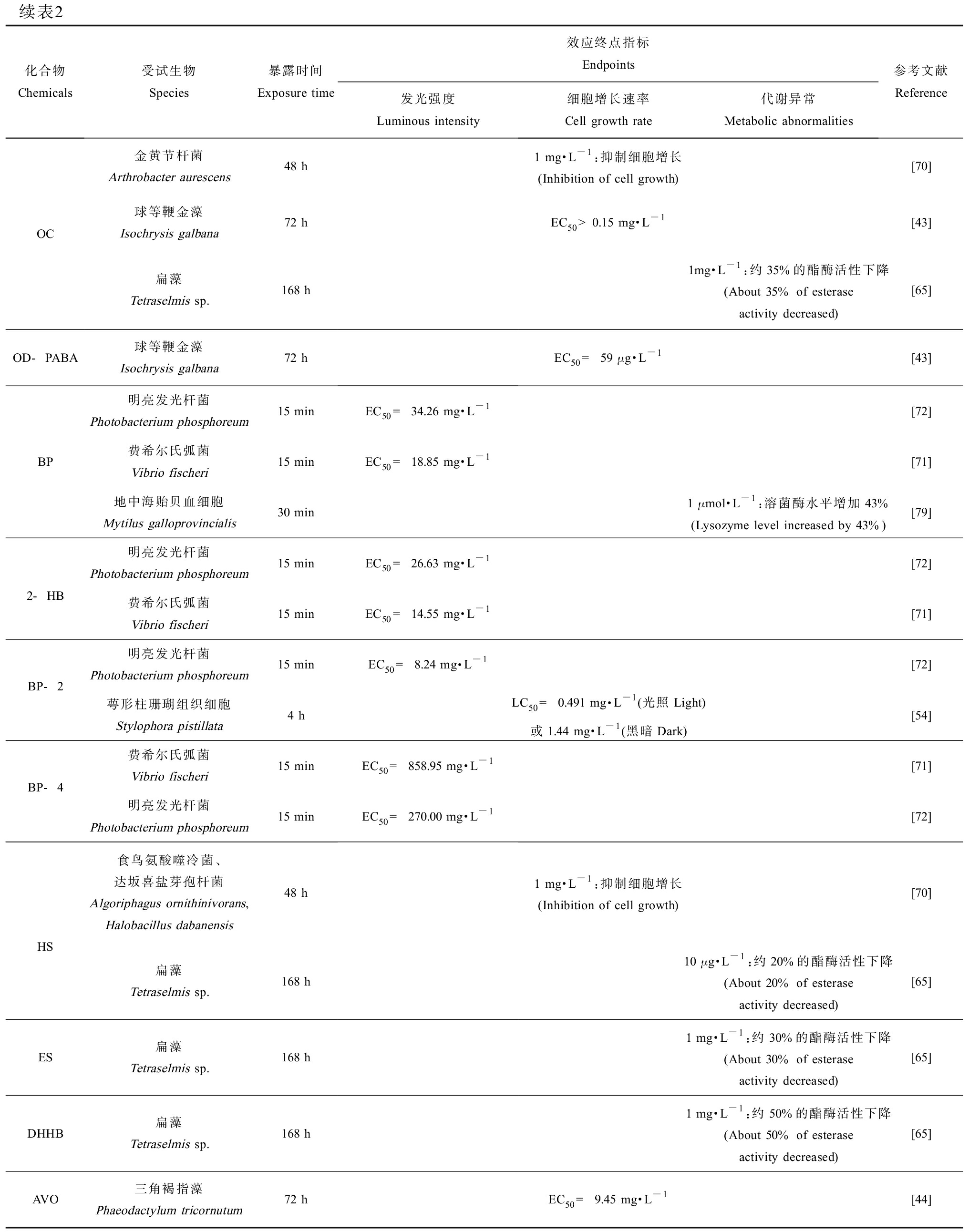

续表2化合物Chemicals受试生物Species暴露时间Exposure time效应终点指标Endpoints发光强度Luminous intensity细胞增长速率Cell growth rate代谢异常Metabolic abnormalities参考文献ReferenceOCOD-PABA金黄节杆菌Arthrobacter aurescens48 h球等鞭金藻Isochrysis galbana72 h扁藻Tetraselmis sp.168 h球等鞭金藻Isochrysis galbana72 h1 mg·L-1:抑制细胞增长(Inhibition of cell growth)[70]EC50>0.15 mg·L-1[43]1mg·L-1:约35%的酯酶活性下降 (About 35% of esterase activity decreased)[65]EC50 = 59 μg·L-1[43]明亮发光杆菌Photobacterium phosphoreum15 minEC50 = 34.26 mg·L-1[72]BP费希尔氏弧菌Vibrio fischeri15 minEC50 = 18.85 mg·L-1[71]地中海贻贝血细胞Mytilus galloprovincialis30 min1 μmol·L-1:溶菌酶水平增加43% (Lysozyme level increased by 43%)[79]2-HB明亮发光杆菌Photobacterium phosphoreum15 minEC50 = 26.63 mg·L-1[72]费希尔氏弧菌Vibrio fischeri15 minEC50 = 14.55 mg·L-1[71]BP-2明亮发光杆菌Photobacterium phosphoreum15 minEC50 = 8.24 mg·L-1[72]萼形柱珊瑚组织细胞Stylophora pistillata4 hLC50 = 0.491 mg·L-1(光照Light)或1.44 mg·L-1(黑暗Dark)[54]BP-4费希尔氏弧菌Vibrio fischeri15 minEC50 = 858.95 mg·L-1[71]明亮发光杆菌Photobacterium phosphoreum15 minEC50 = 270.00 mg·L-1[72]HS食鸟氨酸噬冷菌、达坂喜盐芽孢杆菌Algoriphagus ornithinivorans, Halobacillus dabanensis48 h扁藻Tetraselmis sp.168 hES扁藻Tetraselmis sp.168 hDHHB扁藻Tetraselmis sp.168 hAVO三角褐指藻Phaeodactylum tricornutum72 h1 mg·L-1:抑制细胞增长(Inhibition of cell growth)[70]10 μg·L-1:约20%的酯酶活性下降(About 20% of esterase activity decreased)[65]1 mg·L-1:约30%的酯酶活性下降(About 30% of esterase activity decreased)[65]1 mg·L-1:约50%的酯酶活性下降(About 50% of esterase activity decreased)[65]EC50 = 9.45 mg·L-1[44]

注:BP、2-HB、BP-4和DHHB分别为二苯甲酮、2-羟基二苯甲酮、二苯甲酮-4和二乙氨基羟苯甲酰基苯甲酸己酯;H2O2为过氧化氢;MDA为丙二醛;CAT为过氧化氢酶;APX为抗坏血酸过氧化物酶;RUBPCase为核酮糖-1,5-二磷酸羧化酶/加氧酶。

Note: BP, 2-HB, BP-4 and DHHB are the abbreviations of benzophenone, 2-hydroxybenzophenone, benzophenone-4 and diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate, respectively; H2O2 means hydrogen peroxide; MDA means malondialdehyde; CAT means catalase; APX means ascorbate peroxidase; RUBPCase means ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase.

总体上,OUVs对藻类或者细菌的毒性可以归纳为2点:(1)不同OUVs对细菌或者藻类的毒性不同。例如,HS对海藻(Tetraselmis sp.)生长的抑制程度高于BP-3[65];而BP-3、二苯甲酮-4(benzophenone-4, BP-4)、BP、2-羟基二苯甲酮(2-hydroxybenzophenone, 2-HB)抑制费希尔氏弧菌(Vibrio fischeri)发光的程度依次递增[71];BP-3、2-HB、BP-2、BP-4对明亮发光杆菌(Photobacterium phosphoreum)发光抑制的程度依次递减[72]。不同OUVs对藻类或者细菌毒性的差异可能和它们在生物体内的代谢途径有关,EHMC造成小球藻(Chlorella sp.)体内过氧化氢(hydrogen peroxide, H2O2)、丙二醛(malondialdehyde, MDA)、过氧化氢酶(catalase, CAT)和抗坏血酸过氧化物酶(ascorbate peroxidase, APX)等氧化应激指标的含量或活性显著升高,同时伴随核酮糖-1,5-二磷酸羧化酶/加氧酶(ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, RUBPCase)活性下降,藻类的卡尔文循环受到影响[73];而ES、HS、BP-3、OC和二乙氨基羟苯甲酰基苯甲酸己酯(diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate, DHHB)会抑制扁藻(Tetraselmis sp.)的酯酶活性,降低其脂质代谢能力[65]。(2)不同藻类或细菌抗OUVs毒性的能力不同。例如,三角褐指藻[44](Phaeodactylum tricornutum)抗4-MBC、BP-3和EHMC毒性的能力明显高于球等鞭金藻[13](Isochrysis galbana)。不同藻耐OUVs污染胁迫能力的差异对维持共生体稳定性至关重要。在海洋生态系统中,多种生物(例如珊瑚[74]、海蛞蝓[75]和海葵[76]等)是以共生体的形式存在,宿主和藻类、细菌之间互利共生的关系为其健康生长奠定了基础[77]。在遭遇环境胁迫时,共生体可以通过调整体内藻类或微生物群落结构来对环境产生适应性[78]。在生理机制上,OUVs对藻类生长发育的影响可能是通过破坏机体氧化应激系统、抑制光合作用或能量代谢,因为当藻类暴露于OUVs时,在其体内观察到多种抗氧化酶的上升,以及与光合作用、能量代谢相关酶的下降[65, 73]。

目前,在海洋生物离体细胞上开展OUVs毒理实验,局限于珊瑚和贻贝。Downs等[12, 54]在珊瑚组织细胞上开展BP-2和BP-3的毒理实验,发现部分珊瑚细胞死亡,且BP-3对珊瑚细胞的毒性大于BP-2。Canesi等[79]在地中海贻贝血细胞中开展二苯甲酮(benzophenone, BP)的毒理实验,发现BP造成细胞中的溶酶体膜破损、溶菌酶含量增加和抗氧化系统被激活。

3 总结与展望(Conclusions and future prospects)

随着OUVs的生产与使用量大幅上涨,其生态效应逐渐成为人们关注的焦点,而研究OUVs对海洋生物的毒理效应是评估海洋生态健康风险的基础。本文从体内和体外毒理实验总结了OUVs对海洋生物的危害。OUVs在个体水平上对海洋生物具有致死和生长发育等毒性;在组织水平上会导致组织病变;在分子水平上影响酶活性,导致基因变异、代谢异常等。在体外毒理实验中,OUVs影响海洋细菌、微藻和海洋生物离体细胞的生长及代谢。为了更全面评估OUVs对海洋生物的危害,未来需要在以下几个方面开展更多工作。(1)建立海洋生物毒理实验标准。海水盐度、pH等理化参数和淡水具有差异,为了更客观地反映OUVs对海洋生物的毒性,应该建立基于海水环境的生物毒理实验标准。(2)开展慢性毒理实验。OUVs属于“准”持久性有机污染物,在海洋中赋存时间较长,较低浓度的OUVs在长期的暴露过程中可能会对海洋生物造成较严重的危害,因此慢性毒理学实验更能反映OUVs对海洋生物的潜在危害。(3)开展多种OUVs联合或者OUVs与其他污染物联合作用对海洋生物的毒理研究。海洋环境中存在着多种OUVs,并且与其他类型污染物(例如微塑料)共存,而污染物联合作用可能会加剧其对海洋生物的毒性。(4)开发更加科学与精准的毒理效应量化指标。效应终点量化是准确评估毒性的基础,而某些效应终点,例如珊瑚白化,因缺乏精准的测量方法而导致量化误差较大。随着OUVs对海洋生物毒性相关毒理数据的完善,相信未来能够更加科学、准确地评估OUVs对海洋生态环境所造成的危害。

[1] 仝天衡, 杨慧婷, 陈辉辉, 等. 紫外吸收剂在湖泊中的分布及其对底栖动物的毒性效应[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2019, 14(3): 1-17

Tong T H, Yang H T, Chen H H, et al. Distribution of UV absorbers in lake environment and their toxicological effects on benthic animals [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2019, 14(3): 1-17 (in Chinese)

[2] Kameda Y, Kimura K, Miyazaki M. Occurrence and profiles of organic sun-blocking agents in surface waters and sediments in Japanese rivers and lakes [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2011, 159(6): 1570-1576

[3] Tsui M M, Leung H W, Kwan B K, et al. Occurrence, distribution and ecological risk assessment of multiple classes of UV filters in marine sediments in Hong Kong and Japan [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2015, 292: 180-187

[4] Bachelot M, Li Z, Munaron D, et al. Organic UV filter concentrations in marine mussels from French coastal regions [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2012, 420: 273-279

[5] Pegoraro C N, Harner T, Su K, et al. Occurrence and gas-particle partitioning of organic UV-filters in urban air [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2020, 54(20): 12881-12889

[6] Gago-Ferrero P, Alonso M B, Bertozzi C P, et al. First determination of UV filters in marine mammals. Octocrylene levels in Franciscana dolphins [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2013, 47(11): 5619-5625

[7] Peng X Z, Fan Y J, Jin J B, et al. Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of ultraviolet absorbents in marine wildlife of the Pearl River Estuarine, South China Sea [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 225: 55-65

[8] Mitchelmore C L, He K, Gonsior M, et al. Occurrence and distribution of UV-filters and other anthropogenic contaminants in coastal surface water, sediment, and coral tissue from Hawaii [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 670: 398-410

[9] Sang Z Y, Leung K S Y. Environmental occurrence and ecological risk assessment of organic UV filters in marine organisms from Hong Kong coastal waters [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 566-567: 489-498

[10] Falfushynska H, Sokolov E P, Fisch K, et al. Biomarker-based assessment of sublethal toxicity of organic UV filters (ensulizole and octocrylene) in a sentinel marine bivalve Mytilus edulis [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 798: 149171

[11] Araújo M J, Rocha R J M, Soares A M V M, et al. Effects of UV filter 4-methylbenzylidene camphor during early development of Solea senegalensis Kaup, 1858 [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 628-629: 1395-1404

[12] Downs C A, Kramarsky-Winter E, Segal R, et al. Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the U.S. virgin islands [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2016, 70(2): 265-288

[13] Paredes E, Perez S, Rodil R, et al. Ecotoxicological evaluation of four UV filters using marine organisms from different trophic levels Isochrysis galbana, Mytilus galloprovincialis, Paracentrotus lividus, and Siriella armata [J]. Chemosphere, 2014, 104: 44-50

[14] Hong H Z, Wang J X, Shi D L. Effects of salinity on the chronic toxicity of 4-methylbenzylidene camphor (4-MBC) in the marine copepod Tigriopus japonicus [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2021, 232: 105742

[15] Santonocito M, Salerno B, Trombini C, et al. Stress under the sun: Effects of exposure to low concentrations of UV-filter 4- methylbenzylidene camphor (4-MBC) in a marine bivalve filter feeder, the Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2020, 221: 105418

[16] 朱小山, 黄静颖, 吕小慧, 等. 防晒剂的海洋环境行为与生物毒性[J]. 环境科学, 2018, 39(6): 2991-3002

Zhu X S, Huang J Y, Lv X H, et al. Fate and toxicity of UV filters in marine environments [J]. Environmental Science, 2018, 39(6): 2991-3002 (in Chinese)

[17] 刘玮, 李航, 赵欣研, 等. 防晒剂对海洋生态环境的污染及潜在影响[J]. 中华皮肤科杂志, 2021, 54(5): 456-458

Liu W, Li H, Zhao X Y, et al. Sunscreen pollution of marine ecosystems and its potential impact [J]. Chinese Journal of Dermatology, 2021, 54(5): 456-458 (in Chinese)

[18] Lozano C, Givens J, Stien D, et al. Bioaccumulation and toxicological effects of UV-filters on marine species [J]. Sunscreens in Coastal Ecosystems, 2020, 1: 85-130

[19] Caloni S, Durazzano T, Franci G, et al. Sunscreens’ UV filters risk for coastal marine environment biodiversity: A review [J]. Diversity, 2021, 13(8): 374

[20] Rainieri S, Barranco A, Primec M, et al. Occurrence and toxicity of musks and UV filters in the marine environment [J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2017, 104: 57-68

[21] Bakand S, Winder C, Khalil C, et al. Toxicity assessment of industrial chemicals and airborne contaminants: Transition from in vivo to in vitro test methods: A review [J]. Inhalation Toxicology, 2005, 17(13): 775-787

[22] Wernersson A S, Carere M, Maggi C, et al. The European technical report on aquatic effect-based monitoring tools under the water framework directive [J]. Environmental Sciences Europe, 2015, 27(1): 1-11

[23] De Baat M L, van der Oost R, van der Lee G H, et al. Advancements in effect-based surface water quality assessment [J]. Water Research, 2020, 183: 116017

[24] van de Merwe J P, Neale P A, Melvin S D, et al. In vitro bioassays reveal that additives are significant contributors to the toxicity of commercial household pesticides [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2018, 199: 263-268

[25] Al-Ammari A, Zhang L, Yang J Z, et al. Toxicity assessment of synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles in fresh water algae Chlorella pyrenoidosa and a zebrafish liver cell line [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2021, 211: 111948

[26] Hess F D. A Chlamydomonas algal bioassay for detecting growth inhibitor herbicides [J]. Weed Science, 1980, 28(5): 515-520

[27] Ivask A, Kurvet I, Kasemets K, et al. Size-dependent toxicity of silver nanoparticles to bacteria, yeast, algae, crustaceans and mammalian cells in vitro [J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(7): e102108

[28] Huang Y R, Law J C, Lam T K, et al. Risks of organic UV filters: A review of environmental and human health concern studies [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 755(Pt 1): 142486

[29] Catalano R, Labille J, Gaglio D, et al. Safety evaluation of TiO2 nanoparticle-based sunscreen UV filters on the development and the immunological state of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus [J]. Nanomaterials, 2020, 10(11): 2102

[30] Barmo C, Ciacci C, Canonico B, et al. In vivo effects of n-TiO2 on digestive gland and immune function of the marine bivalve Mytilus galloprovincialis [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2013, 132-133: 9-18

[31] Xia B, Zhu L, Han Q, et al. Effects of TiO2 nanoparticles at predicted environmental relevant concentration on the marine scallop Chlamys farreri: An integrated biomarker approach [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2017, 50: 128-135

[32] Miller R J, Lenihan H S, Muller E B, et al. Impacts of metal oxide nanoparticles on marine phytoplankton [J]. Environmental Science &Technology, 2010, 44(19): 7329-7334

[33] Nataraj B, Maharajan K, Hemalatha D, et al. Comparative toxicity of UV-filter octyl methoxycinnamate and its photoproducts on zebrafish development [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 718: 134546

[34] Kim S, Jung D, Kho Y, et al. Effects of benzophenone-3 exposure on endocrine disruption and reproduction of Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes)—A two generation exposure study [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2014, 155: 244-252

[35] Chen T H, Wu Y T, Ding W H. UV-filter benzophenone-3 inhibits agonistic behavior in male Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens) [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2016, 25(2): 302-309

[36] Coronado M, de Haro H, Deng X, et al. Estrogenic activity and reproductive effects of the UV-filter oxybenzone (2-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl-methanone) in fish [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2008, 90(3): 182-187

[37] Liu H, Sun P, Liu H X, et al. Hepatic oxidative stress biomarker responses in freshwater fish Carassius auratus exposed to four benzophenone UV filters [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2015, 119: 116-122

[38] Barone A N, Hayes C E, Kerr J J, et al. Acute toxicity testing of TiO2-based vs. oxybenzone-based sunscreens on clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris) [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2019, 26(14): 14513-14520

[39] Colás-Ruiz N R, Ramirez G, Courant F, et al. Multi-omic approach to evaluate the response of gilt-head sea bream (Sparus aurata) exposed to the UV filter sulisobenzone [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 803: 150080

[40] Carvalhais A, Pereira B, Sabato M, et al. Mild effects of sunscreen agents on a marine flatfish: Oxidative stress, energetic profiles, neurotoxicity and behaviour in response to titanium dioxide nanoparticles and oxybenzone [J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(4): 1567

[41] Thia E, Chou P H, Chen P J. In vitro and in vivo screening for environmentally friendly benzophenone-type UV filters with beneficial tyrosinase inhibition activity [J]. Water Research, 2020, 185: 116208

[42] 朱新波, 王菊香, 董缪武, 等. 庆大霉素对不同年龄组豚鼠的药动学与耳毒性研究[J]. 中国临床药理学与治疗学, 2004, 9(3): 329-332

Zhu X B, Wang J X, Dong M W, et al. Experimental study on ototoxicity of gentamycin at therapeutic doses in infant or adult Guinea pigs [J]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 2004, 9(3): 329-332 (in Chinese)

[43] Giraldo A, Montes R, Rodil R, et al. Ecotoxicological evaluation of the UV filters ethylhexyl dimethyl p-aminobenzoic acid and octocrylene using marine organisms Isochrysis galbana, Mytilus galloprovincialis and Paracentrotus lividus [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2017, 72(4): 606-611

[44] Vieira Sanches M, Oliva M, De Marchi L, et al. Ecotoxicological screening of UV-filters using a battery of marine bioassays [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 290: 118011

[45] Fent K, Kunz P Y, Zenker A, et al. A tentative environmental risk assessment of the UV-filters 3-(4-methylbenzylidene-camphor), 2-ethyl-hexyl-4-trimethoxycinnam-ate, benzophenone-3, benzophenone-4 and 3-benzylidene camphor [J]. Marine Environmental Research, 2010, 69: S4-S6

[46] Mayer P, Reichenberg F. Can highly hydrophobic organic substances cause aquatic baseline toxicity and can they contribute to mixture toxicity? [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2006, 25(10): 2639-2644

[47] Li V W, Tsui M P, Chen X P, et al. Effects of 4-methylbenzylidene camphor (4-MBC) on neuronal and muscular development in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2016, 23(9): 8275-8285

[48] Shore E A, Huber K E, Garrett A D, et al. Four plastic additives reduce larval growth and survival in the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2022, 175: 113385

[49] 覃祯俊, 余克服, 王英辉. 珊瑚礁生态修复的理论与实践[J]. 热带地理, 2016, 36(1): 80-86

Qin Z J, Yu K F, Wang Y H. Review on ecological restoration theories and practices of coral reefs [J]. Tropical Geography, 2016, 36(1): 80-86 (in Chinese)

[50] He T T, Tsui M M P, Tan C J, et al. Comparative toxicities of four benzophenone ultraviolet filters to two life stages of two coral species [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 651(Pt 2): 2391-2399

[51] Wong M, Uppaluri C, Medina A, et al. The four elements of within-group conflict in animal societies: An experimental test using the clown anemonefish, Amphiprion percula [J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2016, 70(9): 1467-1475

[52] Chen T H, Hsieh C Y, Ko F C, et al. Effect of the UV-filter benzophenone-3 on intra-colonial social behaviors of the false clown anemonefish (Amphiprion ocellaris) [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 644: 1625-1629

[53] 李淑, 余克服. 珊瑚礁白化研究进展[J]. 生态学报, 2007, 27(5): 2059-2069

Li S, Yu K F. Recent development in coral reef bleaching research [J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2007, 27(5): 2059-2069 (in Chinese)

[54] Downs C A, Kramarsky-Winter E, Fauth J E, et al. Toxicological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, benzophenone-2, on planulae and in vitro cells of the coral, Stylophora pistillata [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2014, 23(2): 175-191

[55] Danovaro R, Bongiorni L, Corinaldesi C, et al. Sunscreens cause coral bleaching by promoting viral infections [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2008, 116(4): 441-447

[56] Guyon A, Smith K F, Charry M P, et al. Effects of chronic exposure to benzophenone and diclofenac on DNA methylation levels and reproductive success in a marine copepod [J]. Journal of Xenobiotics, 2018, 8(1): 7674

[57] 方春华, 乔琨, 刘智禹, 等. 海洋生物中抗氧化酶的研究进展[J]. 渔业研究, 2016, 38(4): 331-342

Fang C H, Qiao K, Liu Z Y, et al. The research progress of antioxidant enzymes in marine organisms [J]. Journal of Fisheries Research, 2016, 38(4): 331-342 (in Chinese)

[58] Chaves Lopes F, de Castro M R, Caldas Barbosa S, et al. Effect of the UV filter, benzophenone-3, on biomarkers of the yellow clam (Amarilladesma mactroides) under different pH conditions [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2020, 158: 111401

[59] Cuccaro A, Oliva M, De Marchi L, et al. Biochemical response of Ficopomatus enigmaticus adults after exposure to organic and inorganic UV filters [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2022, 178: 113601

[60] Ziarrusta H, Mijangos L, Picart-Armada S, et al. Non-targeted metabolomics reveals alterations in liver and plasma of gilt-head bream exposed to oxybenzone [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 211: 624-631

[61] Stien D, Clergeaud F, Rodrigues A M S, et al. Metabolomics reveal that octocrylene accumulates in Pocillopora damicornis tissues as fatty acid conjugates and triggers coral cell mitochondrial dysfunction [J]. Analytical Chemistry, 2019, 91(1): 990-995

[62] Stien D, Suzuki M, Rodrigues A M S, et al. A unique approach to monitor stress in coral exposed to emerging pollutants [J]. Scientific Reports, 2020, 10(1): 1-11

[63] Zhang P, Lu G H, Liu J C, et al. Toxicological responses of Carassius auratus induced by benzophenone-3 exposure and the association with alteration of gut microbiota [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 747: 141255

[64] O’Donovan S, Mestre N C, Abel S, et al. Effects of the UV filter, oxybenzone, adsorbed to microplastics in the clam Scrobicularia plana [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 733: 139102

[65] Thorel E, Clergeaud F, Jaugeon L, et al. Effect of 10 UV filters on the brine shrimp Artemia salina and the marine microalga Tetraselmis sp. [J]. Toxics, 2020, 8(2): 29

[66] Bandeira S O. Marine botanical communities in southern Mozambique: Sea grass and seaweed diversity and conservation [J]. Ambio, 1995, 24: 506-509

[67] Coogan M A, Edziyie R E, La Point T W, et al. Algal bioaccumulation of triclocarban, triclosan, and methyl-triclosan in a North Texas wastewater treatment plant receiving stream [J]. Chemosphere, 2007, 67(10): 1911-1918

[68] 王娜. 山东青岛近岸海域浮游细菌的生态学研究[D]. 青岛: 中国海洋大学, 2008: 5-6

Wang N. The research on bacterioplankton ecology in coastal water of Qindao in Shandong [D]. Qingdao:Ocean University of China, 2008: 5-6 (in Chinese)

[69] 赵红宁, 王学江, 夏四清. 水生生态毒理学方法在废水毒性评价中的应用[J]. 净水技术, 2008, 27(5): 18-24

Zhao H N, Wang X J, Xia S Q. Application of aquatic ecotoxicology in assessment of wastewater toxicity [J]. Water Purification Technology, 2008, 27(5): 18-24 (in Chinese)

[70] Lozano C, Matallana-Surget S, Givens J, et al. Toxicity of UV filters on marine bacteria: Combined effects with damaging solar radiation [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 722: 137803

[71] Zhang Q Y, Ma X Y, Dzakpasu M, et al. Evaluation of ecotoxicological effects of benzophenone UV filters: Luminescent bacteria toxicity, genotoxicity and hormonal activity [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2017, 142: 338-347

[72] Liu H, Sun P, Liu H X, et al. Acute toxicity of benzophenone-type UV filters for Photobacterium phosphoreum and Daphnia magna: QSAR analysis, interspecies relationship and integrated assessment [J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 135: 182-188

[73] Tian L, Huang L, Cui H W, et al. The toxicological impact of the sunscreen active ingredient octinoxate on the photosynthesis activity of Chlorella sp. [J]. Marine Environmental Research, 2021, 171: 105469

[74] Glynn P. Coral reef bleaching: Facts, hypotheses and implications [J]. Global Change Biology, 1996, 2(6): 495-509

[75] Rumpho M E, Summer E J, Manhart J R. Solar-powered sea slugs. Mollusc/algal chloroplast symbiosis [J]. Plant Physiology, 2000, 123(1): 29-38

[76] Howe P L, Reichelt-Brushett A J, Clark M W. Aiptasia pulchella: A tropical cnidarian representative for laboratory ecotoxicological research [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2012, 31(11): 2653-2662

[77] Liang J Y, Yu K F, Wang Y H, et al. Distinct bacterial communities associated with massive and branching scleractinian corals and potential linkages to coral susceptibility to thermal or cold stress [J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 979

[78] Chen B, Yu K F, Liao Z H, et al. Microbiome community and complexity indicate environmental gradient acclimatisation and potential microbial interaction of endemic coral holobionts in the South China Sea [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 765: 142690

[79] Canesi L, Lorusso L C, Ciacci C, et al. Immunomodulation of Mytilus hemocytes by individual estrogenic chemicals and environmentally relevant mixtures of estrogens: in vitro and in vivo studies [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2007, 81(1): 36-44