微塑料是指环境中粒径介于1 μm~5 mm的塑料颗粒、纤维和薄膜等[1-2],主要有2种来源:一是较大的塑料经过风蚀、水蚀和紫外老化等物理化学作用破碎后形成的次级微塑料;二是洗涤剂、制药业以及化妆品中添加的微塑料[3-5],伴随着人类活动释放到环境当中,即为初级微塑料。当微塑料被水生动物摄食后,会使水生动物产生假饱腹感,进而抑制其生长发育[6-7]。同时,微塑料具有巨大的比表面积,能富集重金属、多环芳烃和致病菌等多种污染物质[8-11],形成污染物复合体。因此水生生态系统中的微塑料污染具有潜在的生态风险。

在各类水生生态系统中,河流、湖泊和河口中检出的微塑料密度可达到10 particles·L-1[12-14]。特别是在近海养殖环境,微塑料密度能达到60 particles·L-1[14-15]。这主要来源于养殖设施中塑料制品的广泛使用,例如延绳养殖使用的尼龙绳、泡沫浮筒,吊养使用的网箱、蟹笼等。养殖使用的鱼粉也检出含有(337.5±34.5) particles·kg-1的微塑料[16]。海洋作为陆源输入重要的汇,海洋生态系统中的微塑料污染已然成为环境热点问题[17]。同时,其复合污染作用沿着食物链传递时产生的生物放大作用,逐渐成为人类健康风险评估的一大重要因素,其中主要以鱼类的研究最为广泛[18-20]。鱼类[21]、太平洋牡蛎[22]和桡足类[23]等水生动物的微塑料检出水平以及毒性测试结果表明,不同物种对于环境中微塑料的摄取具有选择差异性。

海绵动物(Phylum Porifera)是在水中营固着生活的多细胞动物[24],是海洋底栖生态系统中的重要组成部分,在全球海洋生态系统中分布广泛[25]。海绵具有极强的滤水能力和多孔的形态特征,滤水效率可达38 L·d-1·g-1(以干质量计) [26]。水流携带着食物从海绵的入水口进入到海绵体内,其中的溶解性有机碳和微型浮游植物、有机物碎屑(<10 μm)等营养成分会被海绵体内的领细胞所摄食[27],其他物质可能会留存在海绵的内层、中胶层和外层的任一区域,代谢产物和未被海绵吸收的物质则会经由海绵的出水孔排出体外。研究表明,海绵可以作为环境中50~200 μm颗粒物的生物监测器[28],这说明环境中的微粒物质能在海绵体内稳定存在。海绵对于其他溶解态的环境污染物,如重金属、有机污染物的生物监测和环境修复作用已被广泛研究[29-35],但其对于海水中微塑料污染的生物修复评估尚未开展研究。海绵的分布广泛,极强的海水过滤能力,对环境中微粒物质的留存能力强,都使海绵成为缓解海洋生态系统中微塑料污染的理想修复生物。本研究首次开展了蜂海绵(Haliclona sp.)、沐浴海绵(Spongia sp.)对微塑料的生物累积和排出实验。通过研究不同种属的海绵动物对不同粒径微塑料去除的动力学过程,为海绵修复海水中微塑料污染提供基础数据,以期构建海绵和其他海洋生物共存的良性局面,进而促进海洋生态系统的可持续性发展。

1 材料与方法(Materials and methods)

1.1 实验动物

海绵采自福建省漳州市东山县陈城镇岐下村的海绵人工养殖场(117°19′57″E,23°36′21″N)。在实验室内将海绵置于经0.45 μm滤膜过滤后的清洁海水中,驯化一周。驯化期间,水温20 ℃,盐度30‰,溶解氧含量3.30 mg·L-1。

1.2 微塑料悬浮液的配制

有研究表明,海绵主要富集环境介质中50~200 μm的微粒物质,且对微粒材质方面没有生物偏好性[28]。本文选用2种粒径(<100 μm和100~300 μm)的颗粒状聚苯乙烯(PS)微塑料。微塑料浓度设置为5 000 particles·L-1。配制2种粒径范围的微塑料母液(3×106 particles·L-1)备用,其中,溶剂为经0.45 μm滤膜过滤后海水(盐度30‰),微塑料分散剂为六偏磷酸钠(Na6O18P6,5 g·L-1)。分别取1 mL 2种粒径范围的微塑料母液用溶剂海水稀释至600 mL。

1.3 微塑料的生物累积

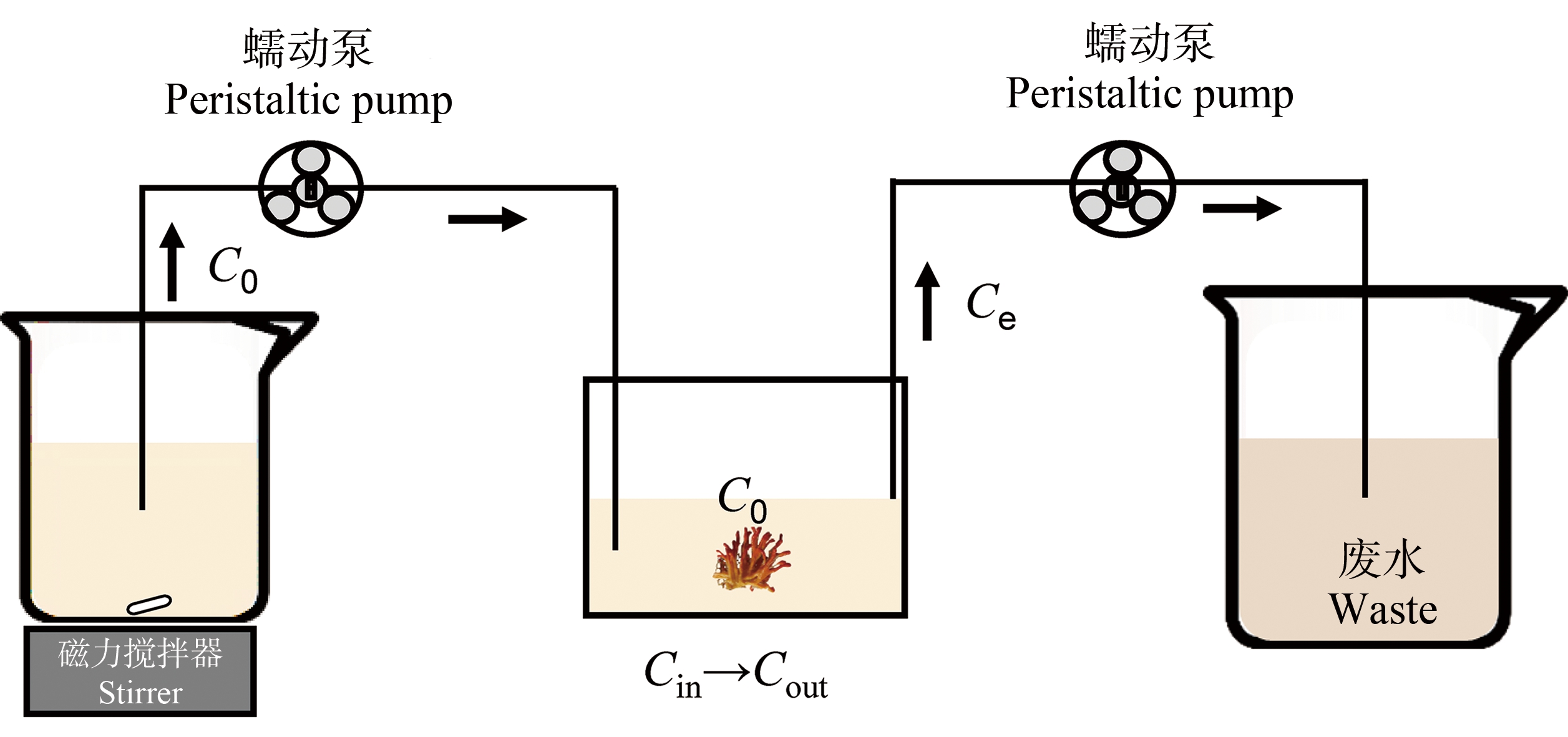

随机选取生理状态良好、大小基本一致(22.0±4.7) g (湿质量)的蜂海绵和沐浴海绵,进行微塑料的生物累积实验(图1)。实验设3个平行组,每组3只海绵。参照清滤率实验中的稳态模型(Steady-State Model)[36],设计微塑料的海绵生物累积实验,设计模型如公式(1)所示。

Ce.rate=(C0×Q-Ce×Q-Ce×CR×BM)/V

(1)

式中:Ce.rate为微塑料排出速率(particles·L-1·d-1);C0为入口浓度(particles·L-1);Ce为出口浓度(particles·L-1);Q为流速(L·d-1);CR为海绵清滤率(L·g-1·d-1);BM为生物量(g) (干质量);V为体系体积(L)。

图1 海绵生物累积微塑料连续流动装置示意图

Fig. 1 Diagram of a continuous flow device for sponge bioaccumulating microplastics

使用OpenModal对上述参数进行调整拟合,直至排出的微塑料与入口浓度在一段时间后产生明显差异并趋于稳定。根据本研究前期获得的海绵清滤率和预实验结果,流动装置参数设计为:生物量为1 g干质量的海绵,能在1.6 h以内,稳定去除流速为21.7 L·d-1的0.6 L微塑料溶液中50%以上的微塑料。每20 min取出口处水样进行微塑料计数,直至计数结果相对稳定,实验时间100 min。

微塑料清除比例=

![]() ×100%

×100%

(2)

微塑料累积量=(初始微塑料浓度-累积结束

时刻微塑料浓度)×恒定溶液体积

(3)

1.4 微塑料排出实验

累积实验结束后,立即将海绵转移到0.45 μm过滤后的2 L清洁海水中进行排出实验,实验过程采用磁力搅拌器搅拌水体。分别在第2、4、8、12、24、48和72 h采样。每次采样时,均先将海绵转移至新的2 L清洁海水中,再过滤收集原体系全部海水中的微塑料,并分离粪便相微塑料。实验过程中不喂食。

累积微塑料排出比例=

![]() ×100%

×100%

(4)

累积微塑料总排出比例=

![]() ×100%

×100%

(5)

1.5 微塑料的测定

为减少样品受外来微塑料污染,实验过程全程穿戴棉质实验服、丁腈手套。分离过程用到的容器尽量采用玻璃材质,且实验前均用RO水和超纯水(18.2 MΩ·cm)冲洗2~3次。所有实验溶液都经0.22 μm PC滤膜过滤后使用,海水均用0.45 μm PC滤膜过滤。样品过滤时用锡箔纸密封住过滤装置的开口。设置空白对照,以避免空气粉尘的影响。

1.5.1 微塑料分离

累积实验中,每20 min取10 mL水样,用0.45 μm滤膜过滤。

排出实验中,对于<100 μm微塑料,使用100 μm筛网(150目)过滤全部水样,截留在筛网上的为粪便相微塑料;对于100~300 μm微塑料,则使用300 μm(50目)筛网分离粪便相微塑料。筛网过滤后的水样再用0.45 μm滤膜过滤,保存滤膜用于计数。

1.5.2 微塑料计数

水相微塑料使用光学生物显微镜(重庆奥特BDS400)观察滤膜并计数。粪便相微塑料则是将分离收集的海绵粪便消解(20 mL 30% H2O2,65 ℃水浴加热,12 h),0.45 μm滤膜过滤,再进行显微计数。

1.6 数据分析

利用Excel 2019进行数据的初步处理。多因素方差分析交互作用,post-hoc(TukeyHSD函数)分析显著差异性,R Studio(4.1.2版本)作图。

2 结果(Results)

2.1 海绵对微塑料的生物累积

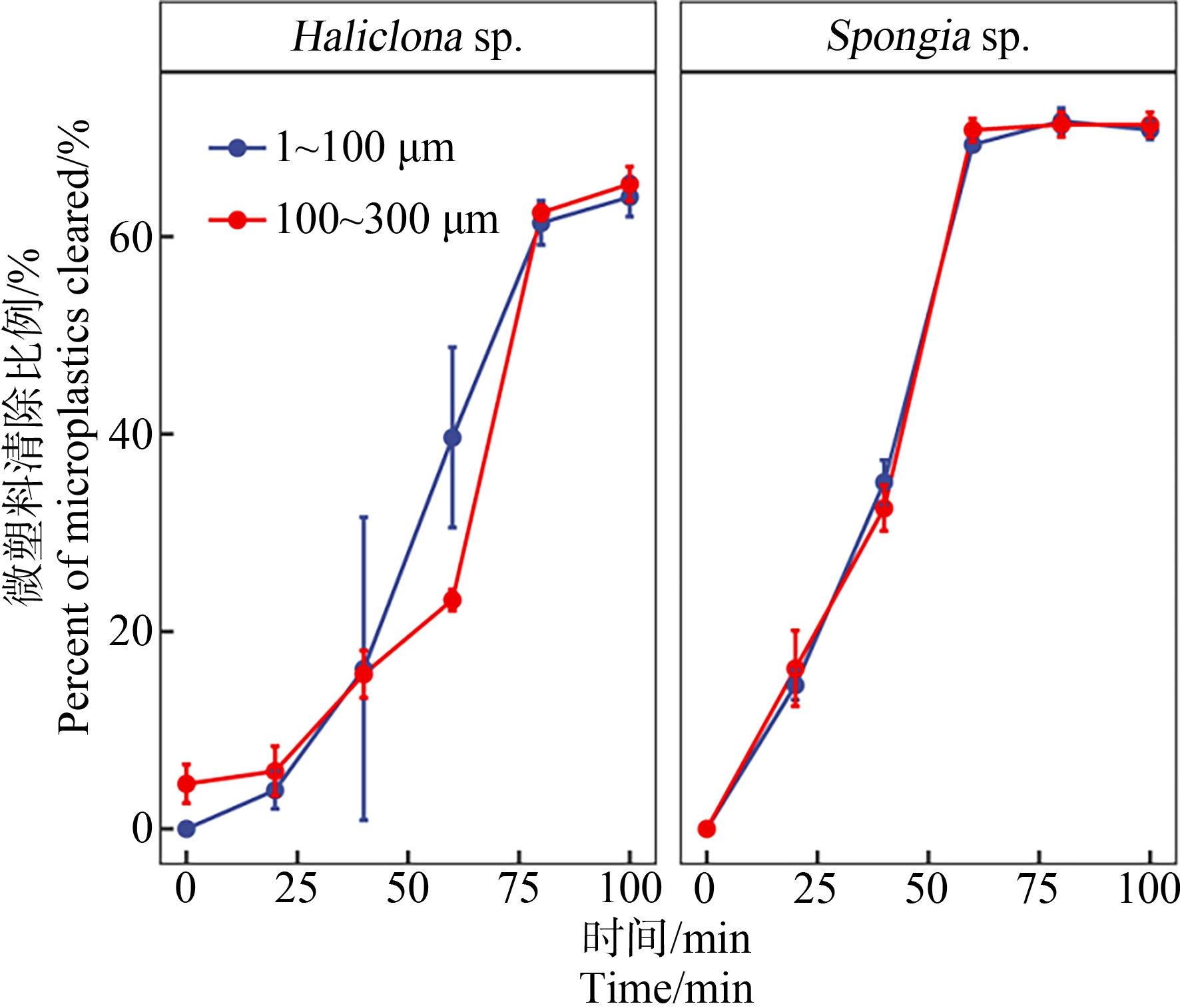

蜂海绵和沐浴海绵对微塑料的生物累积如图2所示。由图2可知,蜂海绵和沐浴海绵均可高效累积2种粒径范围的微塑料,均可在2 h内稳定去除体系中大多数微塑料。其中蜂海绵在实验开始1.6 h后达到累积稳定,对<100 μm和100~300 μm微塑料去除率可达(64.03±2.69)%和(65.34±2.02)%。沐浴海绵也表现出相似的生物累积情况,但累积稳定时间更短(1 h)、累积效率更高;对<100 μm和100~300 μm微塑料去除率分别达到(70.82±0.60)%和(71.36±1.04)%。同种海绵对2种粒径微塑料的生物累积无显著差异。

图2 蜂海绵(Haliclona sp.)和沐浴海绵(Spongia sp.)

对微塑料的生物累积

Fig. 2 Bioaccumulation of microplastics by

Haliclona sp. and Spongia sp.

2.2 海绵对微塑料的排出

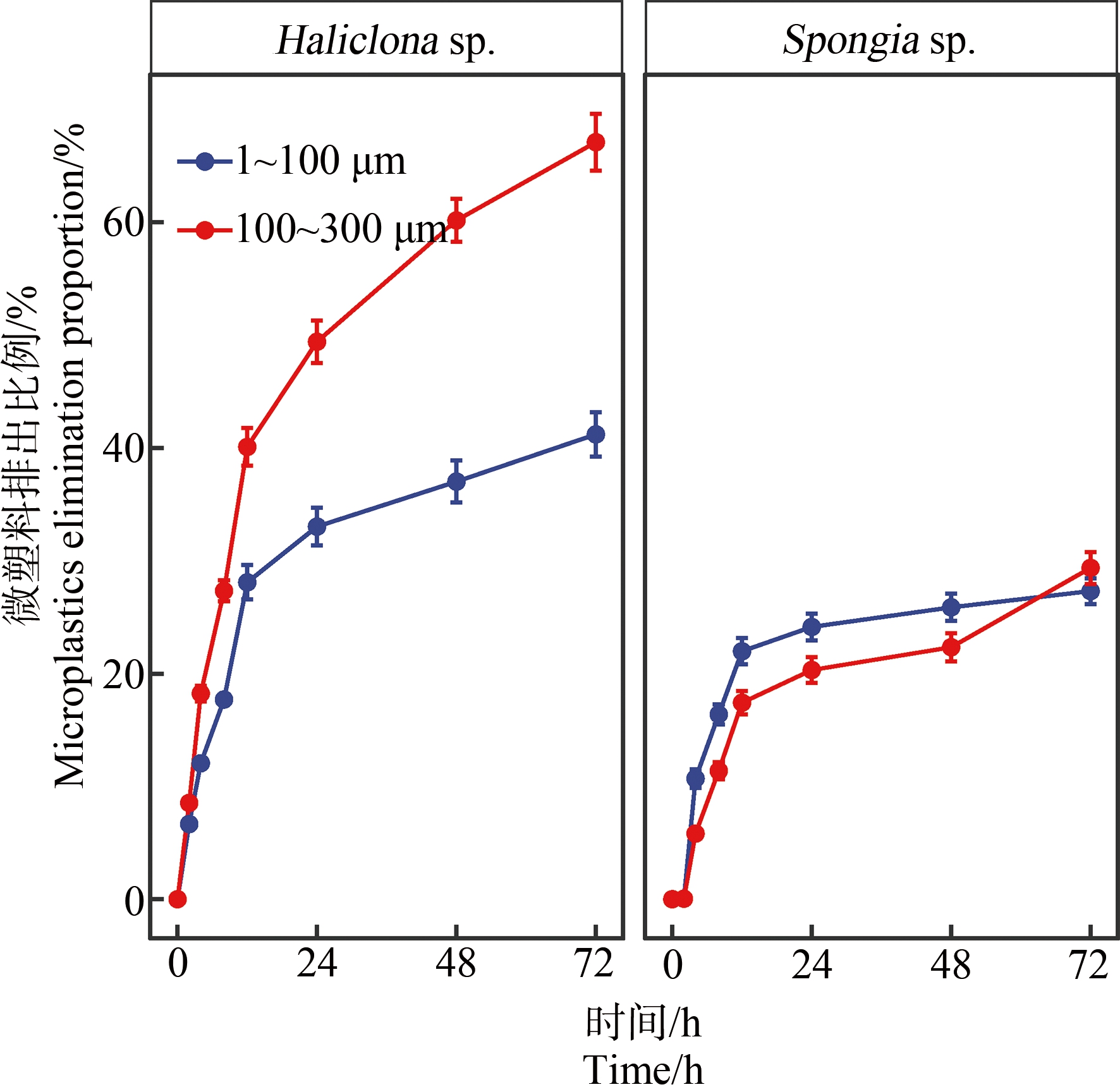

蜂海绵和沐浴海绵的微塑料排出实验结果如图3所示。由图3可知,2种海绵对不同粒径微塑料的排出速率均在第12小时开始趋于稳定,在第72小时均基本停止排出微塑料。对于<100 μm微塑料,蜂海绵和沐浴海绵对体内累积微塑料的排出比例分别为(41.17±2.53)%和(27.31±0.87)%,低于其各自对100~300 μm微塑料的排出比例(67.10±4.21)%和(29.36±1.34)%),由此可见,2种海绵对于体内累积的<100 μm微塑料的留存能力更强。沐浴海绵对2种粒径微塑料的排出比例均低于蜂海绵,说明沐浴海绵对于体内累积微塑料的留存能力更强。

图3 蜂海绵(Haliclona sp.)和沐浴海绵(Spongia sp.)

对微塑料的排出

Fig. 3 Elimination of microplastics by

Haliclona sp. and Spongia sp.

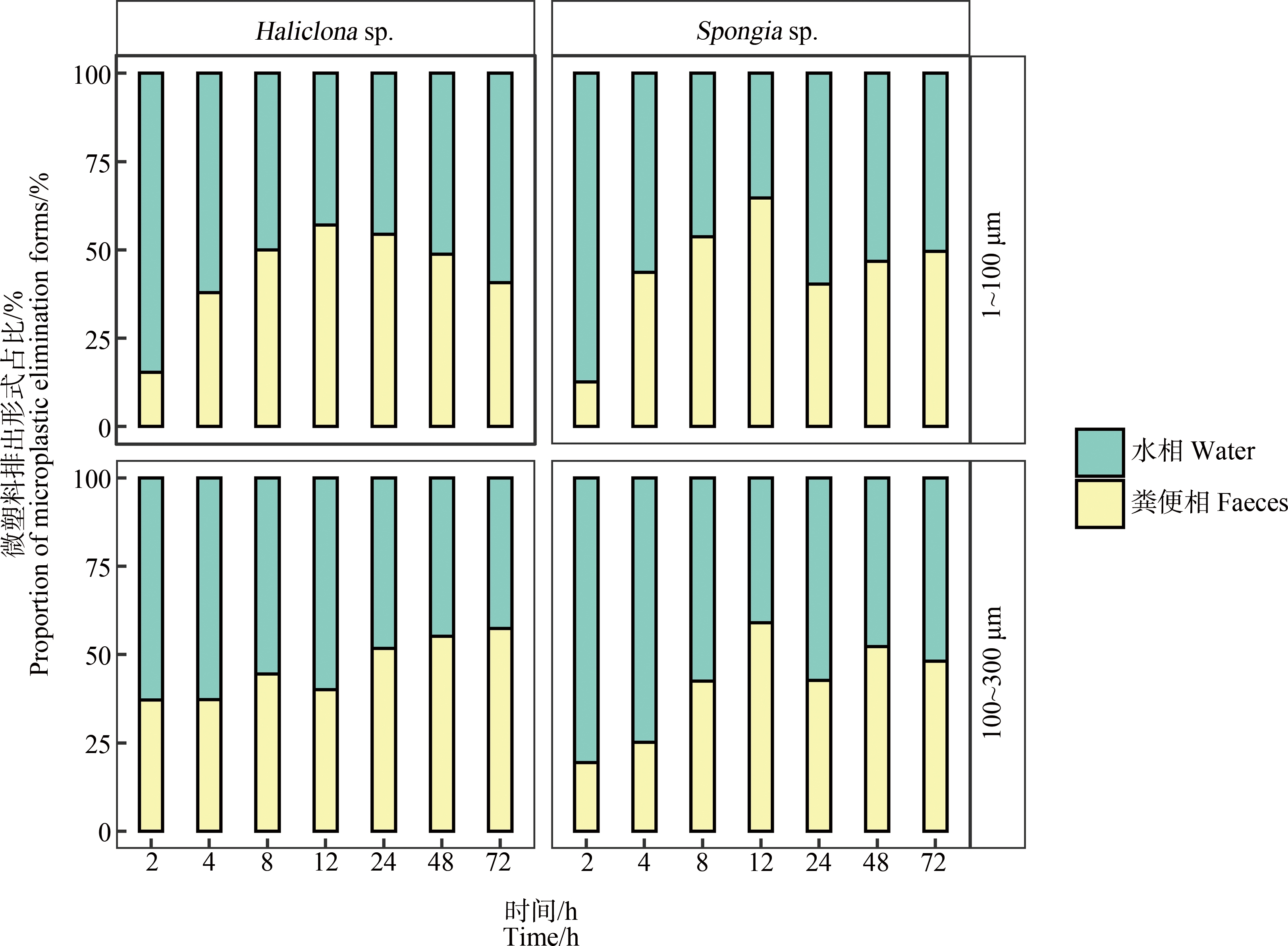

蜂海绵和沐浴海绵排出微塑料的途径如图4所示。由图4可知,在排出实验开始的前12 h,蜂海绵和沐浴海绵主要以水相排出微塑料。随后水相途径排出占比逐渐降低,同时粪便相占比逐渐升高。48 h后,2种排出途径的微塑料占比逐渐趋于均等。

图4 蜂海绵(Haliclona sp.)和沐浴海绵(Spongia sp.)排出微塑料的途径

Fig. 4 Elimination forms of microplastics by Haliclona sp. and Spongia sp.

蜂海绵和沐浴海绵对2种粒径微塑料的总排出率如图5所示。蜂海绵对<100 μm微塑料的排出,经水相、粪便相排出的微塑料占比分别为(23.01±0.07)%和(18.19±2.97)%;对100~300 μm微塑料的排出,经水相、粪便相排出的微塑料占比分别为(33.90±0.94)%和(28.54±0.40)%,水相排出的微塑料占比略高于粪便相,但无显著差异(P>0.1)。沐浴海绵对微塑料的排出与之类似,但对2种粒径微塑料的水相和粪便相排出率均显著低于蜂海绵(P<0.05)。蜂海绵对<100 μm微塑料排出率显著低于其对100~300 μm微塑料的排出率(P<0.05),而沐浴海绵对2种粒径微塑料的排出率无显著差异。

图5 蜂海绵(Haliclona sp.)和沐浴海绵(Spongia sp.)微塑料总排出率

注:不同字母代表有显著差异,P<0.05。

Fig. 5 Total microplastic elimination of Haliclona sp. and Spongia sp.

Note: Different letters represent significant differences, P<0.05.

3 讨论(Discussion)

本研究首次通过室内模拟实验,探究了海绵对海水微塑料的生物累积能力。本研究发现,蜂海绵和沐浴海绵均能够快速、高效地累积海水中的微塑料。Fallon和Freeman[37]通过调查研究也发现,在巴拿马共和国博卡斯德尔托罗省稳定存在的海绵,体内的微塑料检出密度为(169±71) particles·g-1 (以干质量计),高出周围环境介质2~3个数量级。邦加岛的15只珊瑚礁海绵体内微塑料的检测密度为96~612 particles·g-1 (以干质量计)[28]。这都说明,海绵能够长期累积海水中的微塑料,在海洋微塑料污染修复方面具有潜在的应用价值。

海绵累积的微塑料有可能用于自身的生存与发展。Baird和Clifford Alan[38]研究发现,将Tethya bergquistae、Crella incrustans 2种海绵暴露在1 μm和5 μm的塑料溶液中,海绵的呼吸以及对食物颗粒保留并未受到显著影响。而且,海绵倾向于选择50 μm以上的颗粒来支持其骨骼,在骨针中保留50 μm以下的颗粒[39],5 μm以下的微塑料则会被海绵的组织所吸收[40]。本研究也发现海绵对100 μm以下微塑料的留存能力更强。本研究发现沐浴海绵对微塑料的净累积量高于蜂海绵,这可能与其结构有关。沐浴海绵的水沟系统为最复杂的复沟型,具有多个鞭毛室和相对发达的中胶层,体内的领细胞通过鞭毛进行主动滤食时具有更大的流速和流量,对海水中微塑料的截留效率更高。

本研究发现海绵累积环境微塑料后,可以通过水相和粪便相排出部分微塑料。海绵体内累积的微塑料约有10%以粪便的形式排出。这部分微塑料相比于水相中颗粒态微塑料更容易被底栖浮游生物摄食,进而被鱼类、双壳类等水生生物选择性地摄食,可能影响水生动物的生长发育,增加了微塑料通过食物链传递的风险[41]。

除了微塑料,海绵对海水中其他污染物也有很好的耐受性。有研究结果表明,海绵动物对于海水中的重金属[29]、多氯联苯[42]和林丹[31]污染均具有缓解作用,并且其自身能保持相对稳定的微生物群落组成[30]。且在养殖海水中,海绵还会与藻类形成良好的共生局面,藻类既可以为海绵提供自身生长发育所需要的营养物质支持,同时也为海绵体内的共生微生物提供营养元素和有机质[43]。因此,海绵作为实际海水微塑料污染的修复生物具有良好的应用前景。

综上所述,本研究表明:(1)蜂海绵和沐浴海绵均对海水中300 μm以下微塑料具有良好的生物累积能力。(2)沐浴海绵对海水中300 μm以下微塑料的净累积效果较蜂海绵更佳。(3)粒径越小的微塑料越不易被海绵排出。(4)海绵可以通过水相和粪便相排出部分微塑料,2种途径无显著性差异。

[1] Wagner M, Scherer C, Alvarez-Mu oz D, et al. Microplastics in freshwater ecosystems: What we know and what we need to know [J]. Environmental Sciences Europe, 2014, 26(1): 12-21

oz D, et al. Microplastics in freshwater ecosystems: What we know and what we need to know [J]. Environmental Sciences Europe, 2014, 26(1): 12-21

[2] Cole M, Lindeque P, Halsband C, et al. Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: A review [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2011, 62(12): 2588-2597

[3] Fendall L S, Sewell M A. Contributing to marine pollution by washing your face: Microplastics in facial cleansers [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2009, 58(8): 1225-1228

[4] Schwabl P, Köppel S, Königshofer P, et al. Detection of various microplastics in human stool: A prospective case series [J]. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2019, 171(7): 453-457

[5] Zhang L S, Liu J Y, Xie Y S, et al. Occurrence and removal of microplastics from wastewater treatment plants in a typical tourist city in China [J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021, 291: 125968

[6] Taha Z D, Md Amin R, Anuar S T, et al. Microplastics in seawater and zooplankton: A case study from Terengganu Estuary and offshore waters, Malaysia [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 786: 147466

[7] Thompson R C, Moore C J, vom Saal F S, et al. Plastics, the environment and human health: Current consensus and future trends [J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences, 2009, 364(1526): 2153-2166

[8] Brennecke D, Duarte B, Paiva F, et al. Microplastics as vector for heavy metal contamination from the marine environment [J]. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 2016, 178: 189-195

[9] Tang G W, Liu M Y, Zhou Q, et al. Microplastics and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Xiamen coastal areas: Implications for anthropogenic impacts [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 634: 811-820

[10] Sharma M D, Elanjickal A I, Mankar J S, et al. Assessment of cancer risk of microplastics enriched with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 398: 122994

[11] Lamb J B, Willis B L, Fiorenza E A, et al. Plastic waste associated with disease on coral reefs [J]. Science, 2018, 359(6374): 460-462

[12] Andrady A L. Microplastics in the marine environment [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2011, 62(8): 1596-1605

[13] Dubaish F, Liebezeit G. Suspended microplastics and black carbon particles in the jade system, Southern North Sea [J]. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 2013, 224(2): 1352-1360

[14] Li Y Z, Chen G L, Xu K H, et al. Microplastics environmental effect and risk assessment on the aquaculture systems from South China [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021, 18(4): 1869

[15] Ma J L, Niu X J, Zhang D Q, et al. High levels of microplastic pollution in aquaculture water of fish ponds in the Pearl River Estuary of Guangzhou, China [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 744: 140679

[16] Gü![]() E, et al. Fish out, plastic in: Global pattern of plastics in commercial fishmeal [J]. Aquaculture, 2021, 534: 736316

E, et al. Fish out, plastic in: Global pattern of plastics in commercial fishmeal [J]. Aquaculture, 2021, 534: 736316

[17] Cole M, Lindeque P, Halsband C, et al. Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: A review [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2011, 62(12): 2588-2597

[18] Lusher A L, McHugh M, Thompson R C. Occurrence of microplastics in the gastrointestinal tract of pelagic and demersal fish from the English Channel [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2013, 67(1-2): 94-99

[19] Buwono N R, Risjani Y, Soegianto A. Contamination of microplastics in Brantas River, East Java, Indonesia and its distribution in gills and digestive tracts of fish Gambusia affinis [J]. Emerging Contaminants, 2021(1): 172-178

[20] Pannetier P, Cachot J, Clérandeau C, et al. Toxicity Assessment of Pollutants Sorbed on Microplastics Using Various Bioassays on Two Fish Cell Lines [M]//Fate and Impact of Microplastics in Marine Ecosystems. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2017: 140-141

[21] Vendel A L, Bessa F, Alves V E N, et al. Widespread microplastic ingestion by fish assemblages in tropical estuaries subjected to anthropogenic pressures [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2017, 117(1-2): 448-455

[22] Bayne B L, Ahrens M, Allen S K, et al. The proposed dropping of the genus Crassostrea for all Pacific cupped oysters and its replacement by a new genus Magallana: A dissenting view [J]. Journal of Shellfish Research, 2017, 36(3): 545-547

[23] Shore E A, DeMayo J A, Pespeni M H. Microplastics reduce net population growth and fecal pellet sinking rates for the marine copepod, Acartia tonsa [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 284: 117379

[24] Cavalier-Smith T, Allsopp M P, Chao E E, et al. Sponge phylogeny, animal monophyly, and the origin of the nervous system: 18S rRNA evidence [J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 1996, 74(11): 2031-2045

[25] Bell J J, Smith D. Ecology of sponge assemblages (Porifera) in the Wakatobi Region, south-east Sulawesi, Indonesia: Richness and abundance [J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2004, 84(3): 581-591

[26] Gargiulo J C. Inside multi-functional aquarium sponge filter: US5203990 [P]. 1993-04-20

[27] Yahel G, Eerkes-Medrano D I, Leys S P. Size independent selective filtration of ultraplankton by hexactinellid glass sponges [J]. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 2006, 45: 181-194

[28] Girard E B, Fuchs A, Kaliwoda M, et al. Sponges as bioindicators for microparticulate pollutants? [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 268(Pt A): 115851

[29] de Mestre C, Maher W, Roberts D, et al. Sponges as sentinels: Patterns of spatial and intra-individual variation in trace metal concentration [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2012, 64(1): 80-89

[30] Gantt S E, López-Legentil S, Erwin P M. Stable microbial communities in the sponge Crambe crambe from inside and outside a polluted Mediterranean Harbor [J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2017, 364(11): fnx105

[31] Aresta A, Nonnis Marzano C, Lopane C, et al. Analytical investigations on the lindane bioremediation capability of the demosponge Hymeniacidon perlevis [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2015, 90(1-2): 143-149

[32] Rao J V, Srikanth K, Pallela R, et al. The use of marine sponge, Haliclona tenuiramosa as bioindicator to monitor heavy metal pollution in the coasts of Gulf of Mannar, India [J]. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2009, 156(1): 451

[33] Wagner C, Steffen R, Koziol C, et al. Apoptosis in marine sponges: A biomarker for environmental stress (cadmium and bacteria) [J]. Marine Biology, 1998, 131(3): 411-421

[34] Longo C, Corriero G, Licciano M, et al. Bacterial accumulation by the Demospongiae Hymeniacidon perlevis: A tool for the bioremediation of polluted seawater [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2010, 60(8): 1182-1187

[35] Chaves-Fonnegra A, Maldonado M, Blackwelder P, et al. Asynchronous reproduction and multi-spawning in the coral-excavating sponge Cliona delitrix [J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2016, 96(2): 515-528

[36] Larsen P S, Riisgård H U. Validation of the flow-through chamber (FTC) and steady-state (SS) methods for clearance rate measurements in bivalves [J]. Biology Open, 2012, 1(1): 6-11

[37] Fallon B R, Freeman C J. Plastics in Porifera: The occurrence of potential microplastics in marine sponges and seawater from Bocas del Toro, Panamá [J]. PeerJ, 2021, 9: e11638

[38] Baird, Clifford Alan. Measuring the effects of microplastics on sponges [D]. Wellington: Te Kura Mātauranga Koiora, 2016: 30-32

[39] Cerrano C, Calcinai B, Camillo C G D, et al. How and why do sponges incorporate foreign material? Strategies in Porifera [M]// Custódio M R, Gisele Lbo-Hajdu, Hajdu E, et al. Porifera Research: Biodiversity, Innovation and Sustainability. Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional, 2007: 239-246

[40] Leys S P, Eerkes-Medrano D I. Feeding in a calcareous sponge: Particle uptake by pseudopodia [J]. The Biological Bulletin, 2006, 211(2): 157-171

[41] Coppock R L, Galloway T S, Cole M, et al. Microplastics alter feeding selectivity and faecal density in the copepod, Calanus helgolandicus [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 687: 780-789

[42] Wiens M, Koziol C, Hassanein H, et al. Induction of gene expression of the chaperones 14-3-3 and HSP70 by PCB 118 (2,3’,4,4’,5-pentachlorobiphenyl) in the marine sponge Geodia cydonium: Novel biomarkers for polychlorinated biphenyls [J]. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 1998, 165: 247-257

[43] Cerrano C, Calcinai B, Cucchiari E, et al. The diversity of relationships between Antarctic sponges and diatoms: The case of Mycale acerata Kirkpatrick, 1907 (Porifera, Demospongiae) [J]. Polar Biology, 2004, 27(4): 231-237