近年来,畜禽养殖逐渐向集约化、规模化发展,随着动物饲养密度的提高,动物患病风险增加,疾病防控难度也相应增大。据调查显示,70%以上的动物疾病都以病毒性疾病为主[1]。动物病毒性疾病的暴发不仅会影响畜禽产品的质量,导致动物大量死亡,给畜牧业造成巨大经济损失;一些以养殖动物为源头的人畜共患病毒甚至会传播至人居环境,威胁人类健康。例如2009年甲型H1N1流感在全球蔓延[2],2014—2015年H5N2亚型高致病性禽流感在美国暴发等[3],均是由人畜共患病毒引起的大规模流行病疫情。畜禽养殖场作为重要的病毒污染来源,明确其中病毒的分布特征以及向环境中传播的途径及规律,对从源头上控制病毒向人类传播、防止疫情的初期暴发具有重要意义。本文基于对国内外相关研究的分析,对畜禽养殖环境中典型病毒的种类及浓度进行了小结,对其在多种环境介质中的传播规律及影响因素进行了分析,并介绍了养殖场病毒风险多途径控制技术,以期为加强畜禽养殖场病毒风险防控提供参考。

1 病毒在空气中的分布与传播(Distribution and transmission of viruses in air)

1.1 病毒气溶胶的分布(Distribution of viral aerosols)

气溶胶途径是病毒传播的一种重要方式,具有传播速度快、距离远以及难以控制等特点[4]。畜禽养殖场中很多种病毒都可以通过气溶胶进行传播,如猪的甲型流感病毒(influenza A virus, IAV)、口蹄疫病毒(foot-and-mouth disease virus, FMDV)、猪繁殖与呼吸综合征病毒(porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, PRRSV)和猪流行性腹泻病毒(porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, PEDV)等,以及家禽的新城疫病毒(Newcastle disease virus, NDV)、马立克氏病病毒(Marek’s disease virus, MDV)和禽流感病毒(avian influenza virus, AIV)等[5]。病毒气溶胶的传播可造成养殖场内部动物疫病的集中暴发,更可能进一步通过空气扩散,导致邻近养殖场动物的感染,一些人畜共患病毒的气溶胶甚至会形成更大范围的传播,威胁到周边居民的身体健康[4,6]。

多项研究已经在实验室模拟条件下验证了病毒气溶胶的传播风险。李欣[2]发现猪源甲型H1N1流感病毒分离株可形成病毒气溶胶,且能够引起猪群的气源性感染。郝海玉[7]证明感染鸡排出的MDV能形成气溶胶,并会迅速传播感染整个鸡群,且存在传播至邻近禽舍的风险。Kaplan等[8]使用流感病毒感染动物模型评估了甲型H3N2流感病毒气溶胶的传播风险,发现该病毒可通过气溶胶途径从感染猪传染至雪貂,因此推断该病毒可能会通过气溶胶途径由猪传播给人类。

表1总结了畜禽养殖环境中病毒气溶胶的分布特征,可以看出,受感染动物释放的病毒可以在畜禽舍内、养殖场周边以及活禽市场的空气中广泛分布和传播。畜禽舍内相对封闭,病毒气溶胶浓度较高。在位于中国、美国和加拿大等地的畜禽舍内空气样品中,AIV、IAV和猪圆环病毒2型(porcine circovirus type 2, PCV2)等病毒的阳性检出率为23.3%~90.4%[2,4,9-11],其中传染性IAV占阳性样本的16.3%~51.4%[9-10],病毒浓度最高可达106~107 copies·m-3[2,10-11]。当病毒气溶胶从畜禽舍排出后,将进一步随空气扩散,导致周边空气的污染。据报道,在位于中国和美国的一些养猪场附近的空气中,IAV、PEDV和PRRSV等病毒的阳性检出率为4.2%~67.8%[2,9,12-13]。一些病毒气溶胶可顺风传播至较远距离。Brito等[13]在美国某猪场下风向30 m处的空气中检测到PRRSV的浓度高达106 TCID50·mL-1;Alonso等[12]在美国多家猪场下风向0.02~16.09 km 处的空气中检测到PEDV的浓度高达105 copies·m-3;Corzo等[9]最远在猪场下风向2.1 km处检测到IAV的RNA。整体而言,在养殖场和养殖动物密度较高的地区,养殖场周边空气中病毒的检出率、浓度和多样性会更高[13],气溶胶传播途径中的病毒随传播距离的延长,其浓度和风险将逐渐降低。李欣[2]和Corzo等[9]发现猪舍外空气中的IAV浓度比猪舍内低1~3个数量级,当IAV从猪舍排气扇处传播至下风向0.9~2.1 km处时,病毒浓度降低1个数量级,传染性IAV占阳性样本的比例也从1.6%降为0。活禽市场也是病毒气溶胶传播的典型场景之一。活禽市场的家禽来源复杂,且密度较高,病毒可能会发生重组,又因为市场的流通性较大,当病毒气溶胶保持传染性时,可能会感染更多的动物甚至人类。在我国江西、广东等地的活禽市场空气中,AIV曾被检出且其阳性率为7.8%~34.1%[14-15],其中传染性AIV占阳性样本的0.4%~5.3%。

表1 病毒气溶胶在畜禽养殖场及周边环境中的分布

Table 1 Distribution of viral aerosols in livestock and poultry farms and surroundings

采样地点Sampling site国家Country动物类型Animal type病毒名称Virus name总样本数Total number of samples阳性率/%Positive rate/%浓度Concentration传染性样本数Number of infectious samples参考文献Reference畜禽舍内Inside the animal housing中国China鸡Chicken禽流感病毒(AIV)Avian influenza virus (AIV)6023.3--[4]美国USA猪Swine甲型流感病毒(IAV)Influenza A virus (IAV)6071.7(3.20±4.01)×105 copies·m-37[9]美国USA猪Swine甲型流感病毒(IAV)Influenza A virus (IAV)8242.70~1.25×106 copies·m-318[10]中国China猪Swine甲型流感病毒(IAV)Influenza A virus (IAV)15726.11.38×104~5.25×106 copies·m-3-[2]加拿大Canada猪Swine猪圆环病毒2型(PCV2)Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2)5290.42×103~1×107 copies·m-3-[11]养殖场周边地区Surrounding area of the farms美国USA猪Swine甲型流感病毒(IAV)Influenza A virus (IAV)9067.8(1.79±2.49)×104 copies·m-3 (猪舍排气扇处)(At the exhaust fan outside the pigpen)1[9]美国USA猪Swine甲型流感病毒(IAV)Influenza A virus (IAV)1204.21.74×103~8.58×103 copies·m-3(下风向0.9~2.1 km) (Downwind 0.9~2.1 km)0[9]中国China猪Swine甲型流感病毒(IAV)Influenza A virus (IAV)378.11.23×103~2.57×103 copies·m-3(下风向10 m) (Downwind 10 m)-[2]美国USA猪Swine猪流行性腹泻病毒(PEDV)Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV)6217.74.21×103~4.99×105 copies·m-3(下风向0.02~16.09 km) (Downwind 0.02~16.09 km)0[12]美国USA猪Swine猪繁殖与呼吸综合征病毒(PRRSV)Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV)21736.91.00×101~3.16×106 TCID50·mL-1(下风向30 m) (Downwind 30 m)-[13]活禽市场Live poultry market中国China家禽Poultry禽流感病毒(AIV)Avian influenza virus (AIV)80734.1-1[14]中国China家禽Poultry禽流感病毒(AIV)Avian influenza virus (AIV)2437.8-1[15]

注:- 表示参考文献中不包含相关数据。

Note: :- indicates that the reference does not contain relevant data.

1.2 病毒气溶胶的传播影响因素(Influencing factors on viral aerosol transmission)

病毒气溶胶的传播与其载体颗粒(灰尘、粪便、呼吸道液滴、毛发和垫料碎片等)的大小有关[16]。研究显示,随着载体颗粒增大,其负载的病毒数量增多且存活能力增强。Alonso等[16]从饲养实验感染猪的隔离室采集了空气样本,发现感染猪释放的IAV、PRRSV和PEDV分散在各种粒径(0.4~10 μm)的颗粒中,且颗粒越大其负载的病毒浓度越高,如IAV、PRRSV和PEDV的浓度最高值均出现在粒径为9~10 μm的颗粒中,分别为4.3×105、5.1×104和3.5×108 copies·m-3;同时颗粒越大其负载的IAV和PRRSV的存活能力越强,如IAV和PRRSV仅从粒径>2.1 μm的颗粒中分离得到。Zuo等[17]通过实验室气溶胶测试隧道试验,发现传染性病毒和总病毒浓度均随颗粒粒径(100~450 nm)增大而升高,如猪传染性胃肠炎病毒(transmissible gastroenteritis virus, TGEV)、猪流感病毒(swine influenza virus, SIV)和AIV的浓度最大值均出现在400~450 nm的颗粒中,其浓度分别为35、180和60 TCID50·cm-3,且TGEV、SIV和AIV在大粒径(300~450 nm)颗粒下的存活能力明显更高,推测可能与屏蔽效应有关,即较大颗粒中的病毒可能被更多的有机物包围,可以使病毒免受紫外线照射等环境影响,并减少干燥和取样器有关的机械力等采样压力,从而更好地保持病毒的传染性。

病毒气溶胶的传播也与气象因素有关,相对湿度、温度和风可以影响颗粒的沉降时间,从而影响病毒气溶胶的传播轨迹[16]。Pitkin等[18]和Dee等[19]通过构建养猪生产区域模型,发现低温、较高的相对湿度、高气压、日照不足、低风速以及阵风等因素,都可能导致距离感染PRRSV猪群下风向120 m处的气溶胶阳性率增加,如气压每增加一个单位,气溶胶呈PRRSV阳性的几率就增加9%。

2 病毒在水介质中的分布与传播(Distribution and transmission of viruses in aqueous medium)

2.1 病毒的分布(Distribution of viruses)

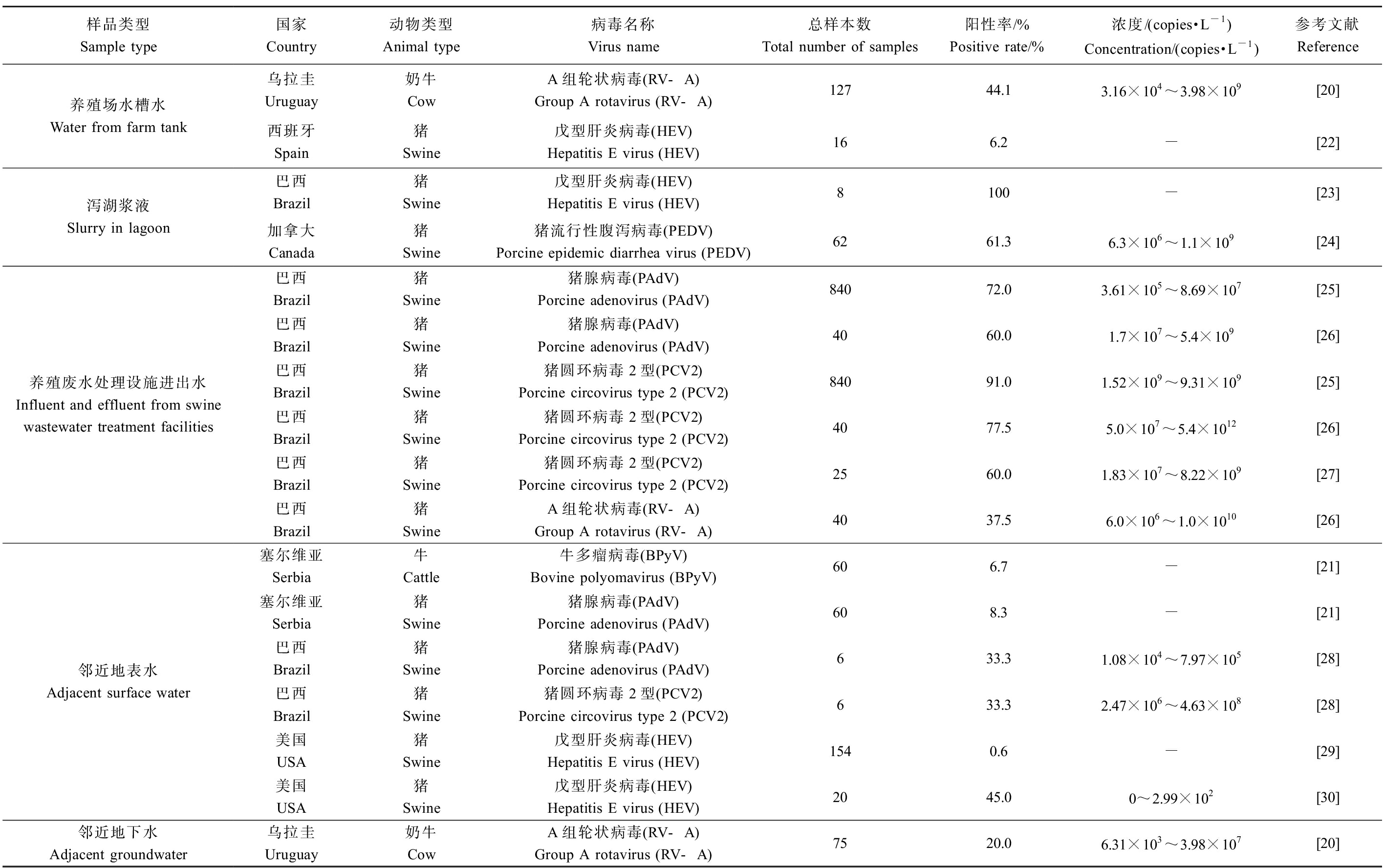

水体是病毒扩散和传播的重要途径,畜禽养殖场中存在的多类病毒如轮状病毒(rotavirus, RV)、戊型肝炎病毒(hepatitis E virus, HEV)、猪腺病毒(porcine adenovirus, PAdV)和牛多瘤病毒(bovine polyomavirus, BPyV)等,都可以通过水介质向环境中迁移[20-21]。表2总结了一些病毒在畜禽养殖场及周边环境水介质中的分布情况,可以看出,受感染动物释放的病毒不仅存在于养殖场饮用水和养殖废水中,而且广泛分布于邻近的地表水和地下水中。

表2 病毒在畜禽养殖场及周边环境水介质中的分布

Table 2 Distribution of viruses in aqueous medium from livestock and poultry farms and surroundings

样品类型Sample type国家Country动物类型Animal type病毒名称Virus name总样本数Total number of samples阳性率/%Positive rate/%浓度/(copies·L-1)Concentration/(copies·L-1)参考文献Reference养殖场水槽水Water from farm tank乌拉圭Uruguay奶牛CowA组轮状病毒(RV-A)Group A rotavirus (RV-A)12744.13.16×104~3.98×109[20]西班牙Spain猪Swine戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)Hepatitis E virus (HEV)166.2-[22]泻湖浆液Slurry in lagoon巴西Brazil猪Swine戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)Hepatitis E virus (HEV)8100-[23]加拿大Canada猪Swine猪流行性腹泻病毒(PEDV)Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV)6261.36.3×106~1.1×109[24]养殖废水处理设施进出水Influent and effluent from swine wastewater treatment facilities巴西Brazil猪Swine猪腺病毒(PAdV)Porcine adenovirus (PAdV)84072.03.61×105~8.69×107[25]巴西Brazil猪Swine猪腺病毒(PAdV)Porcine adenovirus (PAdV)4060.01.7×107~5.4×109[26]巴西Brazil猪Swine猪圆环病毒2型(PCV2)Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2)84091.01.52×109~9.31×109[25]巴西Brazil猪Swine猪圆环病毒2型(PCV2)Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2)4077.55.0×107~5.4×1012[26]巴西Brazil猪Swine猪圆环病毒2型(PCV2)Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2)2560.01.83×107~8.22×109[27]巴西Brazil猪SwineA组轮状病毒(RV-A)Group A rotavirus (RV-A)4037.56.0×106~1.0×1010[26]邻近地表水Adjacent surface water塞尔维亚Serbia牛Cattle牛多瘤病毒(BPyV)Bovine polyomavirus (BPyV)606.7-[21]塞尔维亚Serbia猪Swine猪腺病毒(PAdV)Porcine adenovirus (PAdV)608.3-[21]巴西Brazil猪Swine猪腺病毒(PAdV)Porcine adenovirus (PAdV)633.31.08×104~7.97×105[28]巴西Brazil猪Swine猪圆环病毒2型(PCV2)Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2)633.32.47×106~4.63×108[28]美国USA猪Swine戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)Hepatitis E virus (HEV)1540.6-[29]美国USA猪Swine戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)Hepatitis E virus (HEV)2045.00~2.99×102[30]邻近地下水Adjacent groundwater乌拉圭Uruguay奶牛CowA组轮状病毒(RV-A)Group A rotavirus (RV-A)7520.06.31×103~3.98×107[20]

注:-表示参考文献中不包含相关数据。

Note: -indicates that the reference does not contain relevant data.

在集约化饲养模式下,一些病毒很容易通过饮用水传播,并导致养殖场内部动物的严重感染。Fernández-Barredo等[22]在西班牙某猪场的水槽水中检出HEV,样本阳性率为6.2%。Castells等[20]在乌拉圭多家奶牛场的犊牛水槽水中检出A组轮状病毒(group A rotavirus, RV-A),样本阳性率为44.1%,浓度高达109 copies·L-1,其中部分样本中的RV-A表现出传染性。

集约化畜禽养殖场通常具备不同规模的废水储存或处理设施,常见的有泻湖、厌氧消化和好氧/厌氧组合工艺等。据报道,在位于巴西和加拿大等地的猪场泻湖和废水处理设施进出水中,HEV、PEDV、PAdV、PCV2和RV-A等病毒被检出,样本阳性率为37.5%~100%[23-27]。Fongaro等[26]发现液体猪粪经厌氧消化处理后,出水中PCV2的浓度仍高达1012 copies·L-1,且传染性没有明显降低;Viancelli等[27]从不同猪场废水处理系统(A/O、生物消化池+稳定塘)采集出水,结果有60%的样本呈PCV2阳性,且所有阳性样本均能在体外感染ST细胞,具有传染风险。可见,常见的养殖废水处理工艺并不能有效去除病毒,未能有效阻断病毒向环境传播的风险。

养殖场邻近地表水和地下水可能会受到病毒污染,进而成为疾病传播的媒介。据报道,在美国、巴西等地的养殖场邻近地表水和地下水中,BPyV、PAdV、PCV2、HEV和RV-A等病毒的阳性率为0.6%~45.0%[20-21,28-30],其中Garcia等[28]在巴西猪场邻近的地表水中检测到PCV2的浓度高达108 copies·L-1。邻近地表水和地下水中的病毒可能来源于畜禽养殖废水的直接排放[31],也可能来源于畜禽粪肥的施用,即施用于农田的粪肥可能会在降水或农田灌溉期间释放出病毒,并随地表径流或渗流迁移至地表水或地下水中[32]。Givens等[30]在农田施用猪粪1~3个月后,观察到邻近地表水中HEV的检出率和浓度显著增加,施肥后地表水样本中HEV的检出率增加50%,其浓度也比施肥前增加了1~2个数量级;Krog等[33]发现农田施用猪粪后的第1天,HEV、PCV2和RV-A等病毒通过土壤浸出并进入排水沟,施用猪粪2个月后,在测试场地下3.5 m深的监测井中检测到RV-A。畜禽粪便的泄漏事件也可能导致邻近地表水的污染。Haack等[34]在距离猪粪泄漏入口点的河流下游5.6 km处检测到PAdV和猪捷申病毒(porcine teschovirus, PTV)。

2.2 传播影响因素(Influencing factors on virus transmission)

病毒在水介质中的传播与水温、pH、盐度和微生物等因素有关。低温更有利于病毒在水中的存活。Corsi等[35]对美国密尔沃基河流域3条溪流的样品进行了病毒检测,发现牛轮状病毒(bovine rotavirus, BRV)、牛病毒性腹泻病毒1型(bovine viral diarrhea virus type 1, BVDV1)和BPyV在寒冷月份的总检出率为49%,样本平均病毒浓度为4.8 copies·L-1,在温暖月份的总检出率为30%,样本平均病毒浓度为1.7 copies·L-1,病毒浓度最高的样本来自12月和1月。除低温外,微碱性和低盐度条件也有利于水中病毒的存活和传播。Brown等[36]在实验室模拟条件下考察了12种野生禽类源AIV在不同温度、pH和盐度水体中的传染性,发现大多数AIV在较低温度(4~17 ℃)、微碱性(pH:7.4~8.2)和较低盐度(0~20 000 mg·L-1)条件下相对稳定,而在高温(> 32 ℃)、酸性(pH < 6.6)和高盐度(> 25 000 mg·L-1)条件下,其保持传染性的时间大大缩短。此外,水中微生物的存在也是影响病毒存活的因素之一。Zhang等[37]研究了2种AIV毒株(H5N1和H9N2)在实际淡水和咸水水样中的存活情况,结果显示,水中微生物的存在不利于病毒在淡水(洞庭湖、鄱阳湖和长江)中的存活,淡水水样经0.22 μm膜过滤后,病毒存活时间均明显延长,如H9N2病毒在16 ℃/未过滤和16 ℃/过滤的鄱阳湖水样中保持传染性的时间分别为16 d和23 d,但咸水水样(青海湖)经过滤后,病毒存活时间无明显变化,如H9N2病毒在16 ℃/未过滤和16 ℃/过滤的青海湖水样中保持传染性的时间均为13 d,这可能与青海湖水中较低的微生物含量有关。

病毒在水体中的传播也与河流水文因素有关。由降水或融雪引起的河流径流量增加可能会影响病毒的传播,一方面,污染源可能会被河水稀释,导致病毒浓度降低;另一方面,病毒的传播速度加快,沉淀或失活的可能性降低[35]。

3 病毒在畜禽粪便及土壤中的分布与传播(Distribution and transmission of viruses in animal feces and soil)

3.1 病毒的分布(Distribution of viruses)

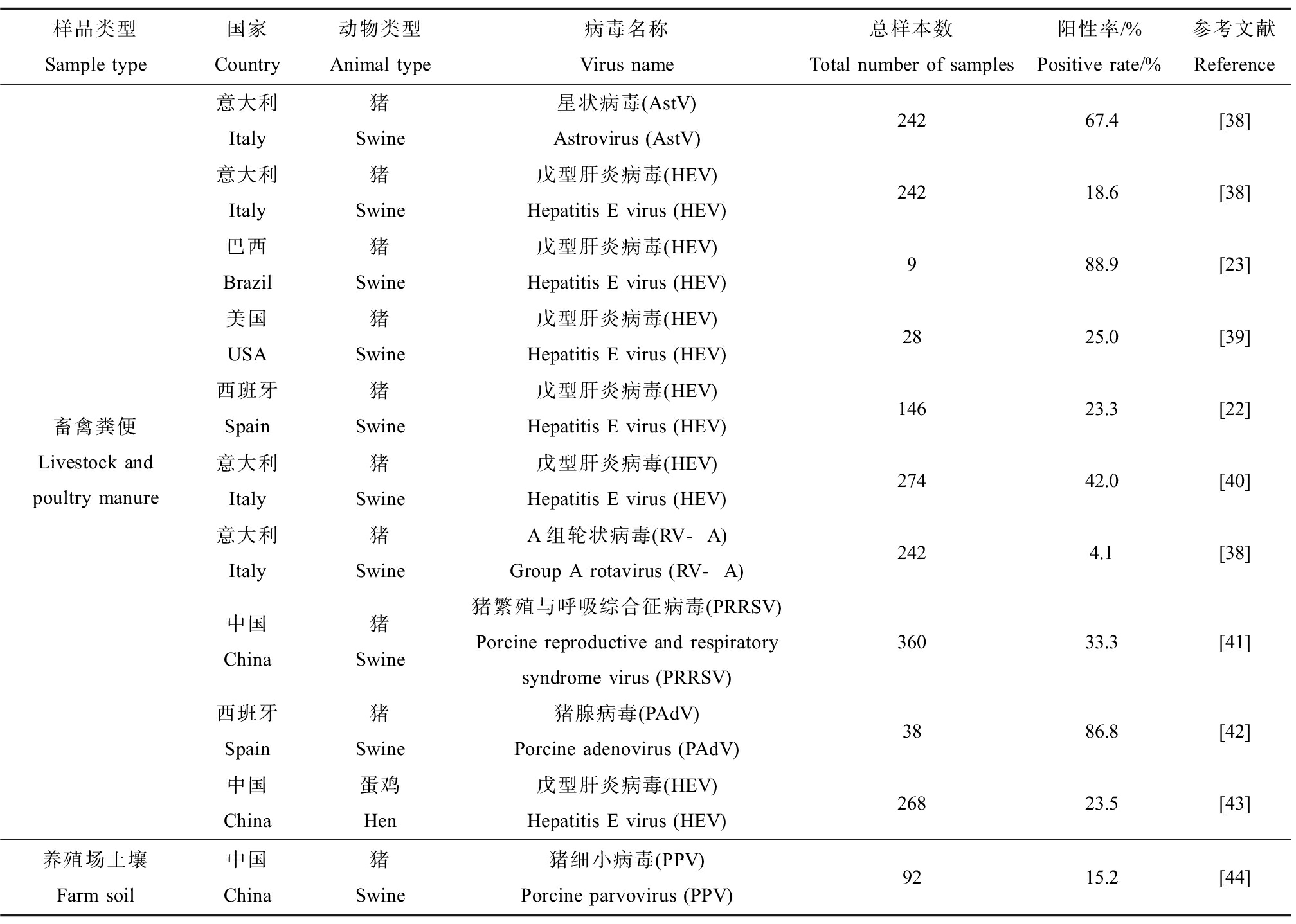

畜禽粪便中可能含有多类病毒,如星状病毒(astrovirus, AstV)、HEV和RV等[38],土壤是畜禽粪便的重要消纳场所,则病毒可能会随着畜禽粪便的处理处置而向土壤中传播。表3总结了一些病毒在畜禽粪便及养殖场邻近土壤中的分布情况,可以看出,受感染动物释放的病毒广泛存在于粪便和邻近土壤中。

畜禽粪便中的病毒检出率及浓度通常较高。研究发现,畜禽粪便中AstV、HEV、RV-A、PRRSV和PAdV等病毒的阳性率为4.1%~88.9%[22-23,38-44],其中传染性PRRSV占阳性样本的11.7%[41],此外不同饲养阶段动物粪便中的病毒阳性率存在差别[22]。Kanai等[45]发现日本感染戊型肝炎的家猪粪便中HEV浓度高达106 copies·g-1,Hundesa等[42]发现西班牙猪粪样本中PAdV的平均浓度达105 copies·g-1。由于畜禽粪肥的施用或运输过程中的泄漏,养殖场附近的土壤也可能会受到污染。涂攀[44]从我国湖北的18个猪场采集了土壤样本,发现有15.2%的样本检出猪细小病毒(porcine parvovirus, PPV)阳性。此外,畜禽粪肥释放的病毒还会在土壤中保持较长时间的传染性,如Fongaro等[46]发现在23 ℃下施用猪粪土壤中的PAdV和RV-A的失活时间均在60 d左右。

3.2 传播影响因素(Influencing factors on virus transmission)

病毒在畜禽粪便和土壤等介质中的传播与温度、含水量、pH和微生物等因素有关。低温条件更有利于畜禽粪便中病毒的存活和传播。Linhares等[47]发现随着温度的升高,猪粪中PRRSV的传染性呈指数下降。Bøtner和Belsham[48]发现在55 ℃的厌氧条件下,猪粪浆中的FMDV仅需40 min就完全失活,而在5 ℃的厌氧条件下,FMDV的存活时间可长达14周。除低温条件外,潮湿、微碱性pH的土壤也有利于病毒的存活。王秋英[49]发现病毒在饱和土壤中的存活率大于在非饱和土壤(50%含水量)中的存活率,病毒在微碱性的沙性潮土(pH=8.05)中的存活时间长于在酸性红壤土中的存活时间。土壤微生物也可能会影响病毒在土壤中的存活。Zhao等[50]发现细菌分泌的胞外聚合物(extracellular polymeric substances, EPS)显著影响红壤土对病毒的去除效果,EPS使红壤土对病毒的去除率降低20%~69%。

4 养殖场病毒传播风险控制(Risk control of virus transmission in farms)

4.1 通风及空气过滤(Ventilation and air filtration)

通风可以快速稀释气溶胶,减少有害微生物和粉尘,有助于防止病毒气溶胶在畜禽舍内的传播。目前,负压通风系统应用较多,其具有结构较简单、投资和管理成本较低等特点[51],可作为病毒气溶胶传播防控的辅助手段。空气过滤可通过物理截留作用防止病毒气溶胶的进一步扩散。Pitkin等[18]将一种两级空气过滤系统结合负压通风应用于养猪生产区域模型,其第一阶段包括6个玻璃纤维预过滤器,能捕获约20%的直径3~10 μm的颗粒,第二阶段包括6个折叠式V字型玻璃纤维过滤器,能捕获约95%的直径0.3~1.0 μm的颗粒,结果显示,安装该空气过滤系统可使区域内猪感染PRRSV的概率从2.8%降至0。

4.2 养殖废水处理(Livestock and poultry breeding wastewater treatment)

在传统畜禽养殖废水处理工艺之外,补充引入对病毒去除更为有效的处理技术可有效降低病毒通过水介质向环境传播的风险。Schmitz等[52]发现高级Bardenpho工艺对病毒的去除效率比传统生物工艺(如活性污泥、生物滴滤塔等)高,经Bardenpho工艺处理后废水中的诺如病毒、肠道病毒、腺病毒和RV-A等11种病毒的平均浓度降低了1.3~3.5 logs。在生物处理段后引入消毒工艺是消除病毒的有效手段。以紫外消毒为例,研究表明,当紫外光的波长为220 nm、剂量为22.5 mJ·cm-2时,污水中RV的失活率可达5.0 logs[53]。

表3 病毒在畜禽粪便及邻近土壤中的分布

Table 3 Distribution of viruses in livestock and poultry manure and adjacent soil medium

样品类型Sample type国家Country动物类型Animal type病毒名称Virus name总样本数Total number of samples阳性率/%Positive rate/%参考文献Reference畜禽粪便Livestock and poultry manure意大利Italy猪Swine星状病毒(AstV)Astrovirus (AstV)24267.4[38]意大利Italy猪Swine戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)Hepatitis E virus (HEV)24218.6[38]巴西Brazil猪Swine戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)Hepatitis E virus (HEV)988.9[23]美国USA猪Swine戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)Hepatitis E virus (HEV)2825.0[39]西班牙Spain猪Swine戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)Hepatitis E virus (HEV)14623.3[22]意大利Italy猪Swine戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)Hepatitis E virus (HEV)27442.0[40]意大利Italy猪SwineA组轮状病毒(RV-A)Group A rotavirus (RV-A)2424.1[38]中国China猪Swine猪繁殖与呼吸综合征病毒(PRRSV)Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV)36033.3[41]西班牙Spain猪Swine猪腺病毒(PAdV)Porcine adenovirus (PAdV)3886.8[42]中国China蛋鸡Hen戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)Hepatitis E virus (HEV)26823.5[43]养殖场土壤Farm soil中国China猪Swine猪细小病毒(PPV)Porcine parvovirus (PPV)9215.2[44]

4.3 畜禽粪便处理(Animal feces treatment)

好氧堆肥是畜禽粪便处理的重要方式,采用适宜的堆肥工艺参数能有效降低粪便堆肥产品中的病毒含量,防止病毒通过粪便资源化途径向农田土壤中传播。Guan等[54]通过堆肥试验证明,堆肥温度在40~50 ℃时,AIV和NDV迅速失活,且堆肥温度在40~60 ℃维持1~2周后,病毒RNA可完全降解。García等[55]对5家西班牙猪粪堆肥厂进行了样品采集,其堆肥过程持续约21 d,且在初始10 d内堆体温度可达65 ℃,该过程可有效消除堆肥原料中的HEV,表明好氧堆肥是一种消除HEV的有效方法。

5 结论与展望(Conclusion and prospect)

受感染动物释放的病毒会在养殖场内部环境中广泛分布和传播,还会通过气溶胶、畜禽废弃物排放与利用等途径向周围环境扩散,造成养殖场周边空气、地表水和土壤等环境中的病毒污染。病毒在不同介质中的传播受温度、湿度等环境因素影响,也与环境介质自身的理化性质相关,总体来说,低温、潮湿和微碱性pH的环境更有利于病毒的存活。对畜禽养殖环境中病毒的环境行为而言,以下内容还需要进一步研究:(1)现有报道多针对畜禽养殖场气溶胶、废水或粪便某一介质中的病毒分布特征开展研究,而对于病毒的跨介质交互与传输过程鲜少涉及;(2)环境介质的物化特性对病毒失活行为的影响机制仍不明确,其与病毒粒子大小、病毒结构组成以及核酸类型等病毒自身特征之间的关联尚需深入探究;(3)养殖动物是多种人畜共患病毒的宿主,畜禽养殖场极有可能是导致人类感染乃至疫情产生的重要源头,因此进一步研究人畜共患病毒由畜禽养殖场向人居环境的传输轨迹与规律,对防控由动物源病毒导致的疫情风险具有重要意义。

[1] 崔茂博, 陈金勇. 基层地区动物疫情处理工作中存在的问题及对策[J]. 吉林农业, 2010(12): 299

[2] 李欣. 猪源H1N1流感病毒在山东猪群中的检测及其气源性传播特点[D]. 泰安: 山东农业大学, 2013: 9, 38-47

Li X. The detection of swine-origin influenzaA (H1N1) virus in swine herd in Shandong and research of its airborne transmission characteristics [D]. Taian: Shandong Agricultural University, 2013: 9, 38-47 (in Chinese)

[3] Leibler J H, Dalton K, Pekosz A, et al. Epizootics in industrial livestock production: Preventable gaps in biosecurity and biocontainment [J]. Zoonoses and Public Health, 2017, 64(2): 137-145

[4] 姚美玲. H9N2亚型禽流感病毒气溶胶发生与传染机制及其感染SPF鸡的特点[D]. 泰安: 山东农业大学, 2010: 20-60

Yao M L. Occurrence and transmission mechanism of avian influenza virus (H9N2 subtype) aerosol and its infection characteristics to the SPF chickens [D]. Taian: Shandong Agricultural University, 2010: 20-60 (in Chinese)

[5] Alonso C, Raynor P C, Goyal S, et al. Assessment of air sampling methods and size distribution of virus-laden aerosols in outbreaks in swine and poultry farms [J]. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 2017, 29(3): 298-304

[6] Schultz A A, Peppard P, Gangnon R E, et al. Residential proximity to concentrated animal feeding operations and allergic and respiratory disease [J]. Environment International, 2019, 130: 104911

[7] 郝海玉. 实验条件下鸡马立克氏病病毒气溶胶的发生、传播与感染的研究[D]. 泰安: 山东农业大学, 2014: 38-40

Hao H Y. The research about generation, transmission and infection of chicken marke’s disease virus (MDV) aerosols under experimental conditions [D]. Taian: Shandong Agricultural University, 2014: 38-40 (in Chinese)

[8] Kaplan B S, Kimble J B, Chang J, et al. Aerosol transmission from infected swine to ferrets of an H3N2 virus collected from an agricultural fair and associated with human variant infections [J]. Journal of Virology, 2020, 94(16): e01009-e01020

[9] Corzo C A, Culhane M, Dee S, et al. Airborne detection and quantification of swine influenza A virus in air samples collected inside, outside and downwind from swine barns [J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(8): e71444

[10] Neira V, Rabinowitz P, Rendahl A, et al. Characterization of viral load, viability and persistence of influenza A virus in air and on surfaces of swine production facilities [J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(1): e0146616

[11] Verreault D, Létourneau V, Gendron L, et al. Airborne porcine circovirus in Canadian swine confinement buildings [J]. Veterinary Microbiology, 2010, 141(3-4): 224-230

[12] Alonso C, Goede D P, Morrison R B, et al. Evidence of infectivity of airborne porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and detection of airborne viral RNA at long distances from infected herds [J]. Veterinary Research, 2014, 45(1): 73

[13] Brito B, Dee S, Wayne S, et al. Genetic diversity of PRRS virus collected from air samples in four different regions of concentrated swine production during a high incidence season [J]. Viruses, 2014, 6(11): 4424-4436

[14] Zeng X X, Liu M B, Zhang H, et al. Avian influenza H9N2 virus isolated from air samples in LPMs in Jiangxi, China [J]. Virology Journal, 2017, 14(1): 136

[15] Wu Y H, Shi W Y, Lin J S, et al. Aerosolized avian influenza A (H5N6) virus isolated from a live poultry market, China [J]. The Journal of Infection, 2017, 74(1): 89-91

[16] Alonso C, Raynor P C, Davies P R, et al. Concentration, size distribution, and infectivity of airborne particles carrying swine viruses [J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(8): e0135675

[17] Zuo Z L, Kuehn T H, Verma H, et al. Association of airborne virus infectivity and survivability with its carrier particle size [J]. Aerosol Science and Technology, 2013, 47(4): 373-382

[18] Pitkin A, Deen J, Dee S. Use of a production region model to assess the airborne spread of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus [J]. Veterinary Microbiology, 2009, 136(1-2): 1-7

[19] Dee S, Otake S, Deen J. Use of a production region model to assess the efficacy of various air filtration systems for preventing airborne transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae: Results from a 2-year study [J]. Virus Research, 2010, 154(1-2): 177-184

[20] Castells M, Schild C, Caffarena D, et al. Prevalence and viability of group A rotavirus in dairy farm water sources [J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2018, 124(3): 922-929

![]() D, et al. Presence of human and animal viruses in surface waters in Vojvodina Province of Serbia [J]. Food and Environmental Virology, 2015, 7(2): 149-158

D, et al. Presence of human and animal viruses in surface waters in Vojvodina Province of Serbia [J]. Food and Environmental Virology, 2015, 7(2): 149-158

[22] Fernández-Barredo S, Galiana C, García A, et al. Detection of hepatitis E virus shedding in feces of pigs at different stages of production using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction [J]. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 2006, 18(5): 462-465

[23] Vasconcelos J, Soliman M, Staggemeier R, et al. Molecular detection of hepatitis E virus in feces and slurry from swine farms, Rio Grande do Sul, Southern Brazil [J]. Arquivo Brasileiro De Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia, 2015, 67(3): 777-782

[24] Tun H M, Cai Z B, Khafipour E. Monitoring survivability and infectivity of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDv) in the infected on-farm earthen manure storages (EMS) [J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 265

[25] Viancelli A, Garcia L A, Kunz A, et al. Detection of circoviruses and porcine adenoviruses in water samples collected from swine manure treatment systems [J]. Research in Veterinary Science, 2012, 93(1): 538-543

[26] Fongaro G, Viancelli A, Magri M E, et al. Utility of specific biomarkers to assess safety of swine manure for biofertilizing purposes [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 479-480: 277-283

[27] Viancelli A, Garcia L A, Schiochet M, et al. Culturing and molecular methods to assess the infectivity of porcine circovirus from treated effluent of swine manure [J]. Research in Veterinary Science, 2012, 93(3): 1520-1524

[28] Garcia L A T, Viancelli A, Rigotto C, et al. Surveillance of human and swine adenovirus, human norovirus and swine circovirus in water samples in Santa Catarina, Brazil [J]. Journal of Water and Health, 2012, 10(3): 445-452

[29] Gentry-Shields J, Myers K, Pisanic N, et al. Hepatitis E virus and coliphages in waters proximal to swine concentrated animal feeding operations [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2015, 505: 487-493

[30] Givens C E, Kolpin D W, Borchardt M A, et al. Detection of hepatitis E virus and other livestock-related pathogens in Iowa streams [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 566-567: 1042-1051

[31] 张强, 刘彬. 畜禽养殖废水处理方法研究与应用[J]. 中国饲料, 2013(17): 8-11

Zhang Q, Liu B. Study on wastewater pollution from livestock and poultry and its treatment technology [J]. China Feed, 2013(17): 8-11 (in Chinese)

[32] Blaustein R A, Pachepsky Y A, Shelton D R, et al. Release and removal of microorganisms from land-deposited animal waste and animal manures: A review of data and models [J]. Journal of Environmental Quality, 2015, 44(5): 1338-1354

[33] Krog J S, Forslund A, Larsen L E, et al. Leaching of viruses and other microorganisms naturally occurring in pig slurry to tile drains on a well-structured loamy field in Denmark [J]. Hydrogeology Journal, 2017, 25(4): 1045-1062

[34] Haack S K, Duris J W, Kolpin D W, et al. Genes indicative of zoonotic and swine pathogens are persistent in stream water and sediment following a swine manure spill [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2015, 81(10): 3430-3441

[35] Corsi S R, Borchardt M A, Spencer S K, et al. Human and bovine viruses in the Milwaukee River watershed: Hydrologically relevant representation and relations with environmental variables [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 490: 849-860

[36] Brown J D, Goekjian G, Poulson R, et al. Avian influenza virus in water: Infectivity is dependent on pH, salinity and temperature [J]. Veterinary Microbiology, 2009, 136(1-2): 20-26

[37] Zhang H B, Li Y, Chen J J, et al. Perpetuation of H5N1 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses in natural water bodies [J]. The Journal of General Virology, 2014, 95(Pt 7): 1430-1435

[38] Monini M, di Bartolo I, Ianiro G, et al. Detection and molecular characterization of zoonotic viruses in swine fecal samples in Italian pig herds [J]. Archives of Virology, 2015, 160(10): 2547-2556

[39] Kasorndorkbua C, Opriessnig T, Huang F F, et al. Infectious swine hepatitis E virus is present in pig manure storage facilities on United States farms, but evidence of water contamination is lacking [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 71(12): 7831-7837

[40] di Bartolo I, Martelli F, Inglese N, et al. Widespread diffusion of genotype 3 hepatitis E virus among farming swine in Northern Italy [J]. Veterinary Microbiology, 2008, 132(1-2): 47-55

[41] Liu J K, Xu Y, Lin Z F, et al. Epidemiology investigation of PRRSV discharged by faecal and genetic variation of ORF5 [J]. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 2021, 68(4): 2334-2344

[42] Hundesa A, Maluquer de Motes C, Albinana-Gimenez N, et al. Development of a qPCR assay for the quantification of porcine adenoviruses as an MST tool for swine fecal contamination in the environment [J]. Journal of Virological Methods, 2009, 158(1-2): 130-135

[43] 拓晓玲. 陕西杨凌蛋鸡场禽戊型肝炎病毒流行情况调查[D]. 杨凌: 西北农林科技大学, 2016: 18

Tuo X L. Prevalence of avian hepatitis E virus infection in laying farms from Yangling, Shannxi Province [D]. Yangling: Northwest A & F University, 2016: 18 (in Chinese)

[44] 涂攀. 猪场土壤中猪细小病毒和链球菌的检测与消毒剂的筛选[D]. 武汉: 华中农业大学, 2011: 36

Tu P. The detection of porcine parvovirus and Streptococcus from pig farm soil and screening of the disinfectant [D]. Wuhan: Huazhong Agricultural University, 2011: 36 (in Chinese)

[45] Kanai Y, Tsujikawa M, Yunoki M, et al. Long-term shedding of hepatitis E virus in the feces of pigs infected naturally, born to sows with and without maternal antibodies [J]. Journal of Medical Virology, 2010, 82(1): 69-76

[46] Fongaro G, Hernández M, García-González M C, et al. Propidium monoazide coupled with PCR predicts infectivity of enteric viruses in swine manure and biofertilized soil [J]. Food and Environmental Virology, 2016, 8(1): 79-85

[47] Linhares D C, Torremorell M, Joo H S, et al. Infectivity of PRRS virus in pig manure at different temperatures [J]. Veterinary Microbiology, 2012, 160(1-2): 23-28

[48] Bøtner A, Belsham G J. Virus survival in slurry: Analysis of the stability of foot-and-mouth disease, classical swine fever, bovine viral diarrhoea and swine influenza viruses [J]. Veterinary Microbiology, 2012, 157(1-2): 41-49

[49] 王秋英. 土壤中病毒的吸附行为及其环境效应[D]. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2006: 2-43

Wang Q Y. Adsorptive behavior of viruses to soils and its significance in the environment [D]. Nanjing: Nanjing Agricultural University, 2006: 2-43 (in Chinese)

[50] Zhao B Z, Jiang Y, Jin Y, et al. Function of bacterial cells and their exuded extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in virus removal by red soils [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2014, 21(15): 9242-9250

[51] 黄藏宇. 猪场微生物气溶胶扩散特征及舍内空气净化技术研究[D]. 金华: 浙江师范大学, 2012: 7-8

Huang C Y. Study on microbiological aerosol transmission and air purification in pig house [D]. Jinhua: Zhejiang Normal University, 2012: 7-8 (in Chinese)

[52] Schmitz B W, Kitajima M, Campillo M E, et al. Virus reduction during advanced bardenpho and conventional wastewater treatment processes [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(17): 9524-9532

[53] Araud E, Fuzawa M, Shisler J L, et al. UV inactivation of rotavirus and tulane virus targets different components of the virions [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2020, 86(4): e02436-e02419

[54] Guan J, Chan M, Grenier C, et al. Survival of avian influenza and Newcastle disease viruses in compost and at ambient temperatures based on virus isolation and real-time reverse transcriptase PCR [J]. Avian Diseases, 2009, 53(1): 26-33

[55] García M, Fernández-Barredo S, Pérez-Gracia M T. Detection of hepatitis E virus (HEV) through the different stages of pig manure composting plants [J]. Microbial Biotechnology, 2014, 7(1): 26-31