-

随着全球人口激增、城市化进程加快以及居民消费方式改变等,全世界每年产生超过20亿吨城市生活垃圾[1]。按照增长速度,2025年和2050年全球城市生活垃圾将分别达到22亿吨和42亿吨[2]。我国城市生活垃圾与工业固体废物年产量逐年增多,2018年我国生活垃圾年产量已达到2.28亿吨,工业固体废物年产量也一直维持在较高水平[3]。

由于固体废物产量日渐增多,因此处理固体废物成为一项艰巨的任务。处置固体废物的主要方式有卫生填埋、堆肥和焚烧[4]。其中,焚烧是目前较为被认可的一种固体废物处置技术[5],不仅可将固体废物质量减少70%,体积减少90%[6],还可以回收热能和电能[7]。2016年,全球约有1179座城市生活垃圾焚烧厂,总处理量为每天70万吨 [8]。2008年至2019年,我国垃圾焚烧厂的数量也在逐渐增多,从74座上升到389座[3],年焚烧量达到了1.02亿吨。在焚烧过程中会产生二噁英(polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzodurans, PCDD/Fs)、多氯联苯(polychlorinated biphenyl, PCBs)、多氯萘(polychlorinated naphthalenes, PCNs)、六氯苯(hexachlorobenzene)、五氯苯(pentachlorobenzene)和多环芳烃(polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, PAHs)等持久性有机污染物[9],由于这些持久性有机污染物具有较强致癌性、毒性、持久性以及生物累积性[10-11],因此被列入《关于持久性有机污染物的斯德哥尔摩公约》。其中PCDD/Fs与PCNs等的生成和排放显著相关[12],且PCBs与PCNs等结构有一定相似性。因此本文分析了代表性的污染物PCDD/Fs、PCBs和PAHs。这些污染物的产生与固废组分息息相关。

目前,国内外学者对单一城市生活垃圾焚烧产生有机污染物的研究相对较多,尤其是对PCDD/Fs的研究更加成熟。Zhu等[13]在2016年采集了中国北方地区6座垃圾焚烧厂的烟气样品,烟气中PCDD/Fs的排放浓度和毒性当量分别为0.11—2.53 ng·Nm−3和0.007—0.059 ng I-TEQ·Nm−3。有学者对国内15座焚烧炉进行采样分析,烟气中PCDD/Fs的毒性当量浓度范围为0.01—8.12 ng I-TEQ·Nm−3[14]。张怀强[15]对3座医疗废物焚烧厂的烟气样品进行监测,烟气中PCDD/Fs毒性当量范围为0.34—11.06 ng I-TEQ·Nm−3。刘劲松等[16]对我国7座医疗废物焚烧炉排放烟气中PCDD/Fs进行监测,其浓度范围为(5.93±2.10)—(67.52±8.24) ng I-TEQ·Nm−3。整体可以看出,不同类型固废焚烧产生的有机污染物的浓度水平存在差异。当前我国焚烧厂主要处理城市生活垃圾,而工业固体废物的处理也同样亟待解决。我国工业固废产量高、处置缺口大,生活垃圾则面临含水率高、热值低等问题[17]。经研究发现一般工业固废(建筑废弃物、生产边角料及废弃塑料、木材等)与生活垃圾混烧既能增加热值,又能起到减量化的作用[18]。因此生活垃圾与工业固废混烧的研究越来越引起人们的关注。

为了有效减少固体废物的数量和毒性,同时实现能源的高效回收,我国提出了可以将生活垃圾与一些危险废物或工业固废协同处置的法律法规。如《国家危险废物名录》的豁免管理清单中规定市政污泥、铜板、线路板、含铬皮革废碎料等危险废物可以与城市生活垃圾一同处置[19]。在《生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准》中提到“在不影响生活垃圾焚烧炉污染物排放达标和焚烧炉正常运行的前提下,生活污水处理设施产生的污泥和一般工业固体废物可以进入生活垃圾焚烧炉进行焚烧处置”等[20]。焚烧对固体废物的热值有一定要求,根据联合国环境规划署(United Nations Environment Programme, UNEP)的规定,当垃圾的低位热值为3350—7100 kJ·kg−1时,适合焚烧处理[21]。当固体废物低位热值≤3350 kJ·kg−1时,需添加辅助燃料进行燃烧。而工业固废的热值较高,可以弥补生活垃圾热值低的缺点。因此,一些工业固废可以和城市生活垃圾一起处置。

本文主要对固体废物混烧中二噁英、多氯联苯和多环芳烃等有机污染物的形成机理和排放特征以及在焚烧过程中如何控制有机污染物生成进行了探究。

-

二噁英是多氯代二苯并二噁英(polychlorodibenzo-p-dioxins, PCDDs)和多氯代二苯并呋喃(polychloro-dibenzofurans, PCDFs)的统称,常写成“PCDD/Fs”。PCDD/Fs主要在锅炉或焚烧炉的燃烧后区形成,具体可分为非均相反应(200—500 ℃)和均相反应(500—800 ℃)[22-23]。

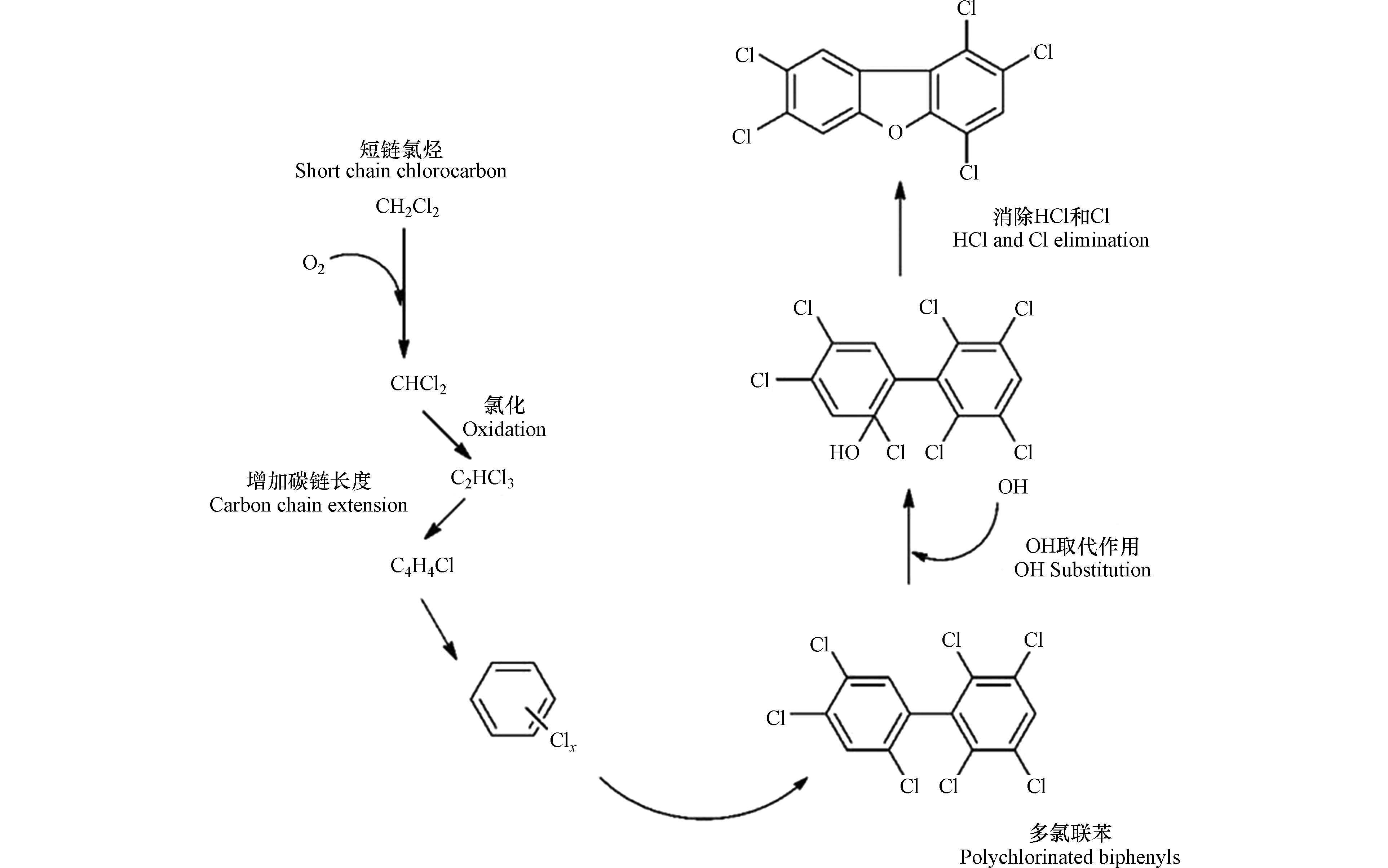

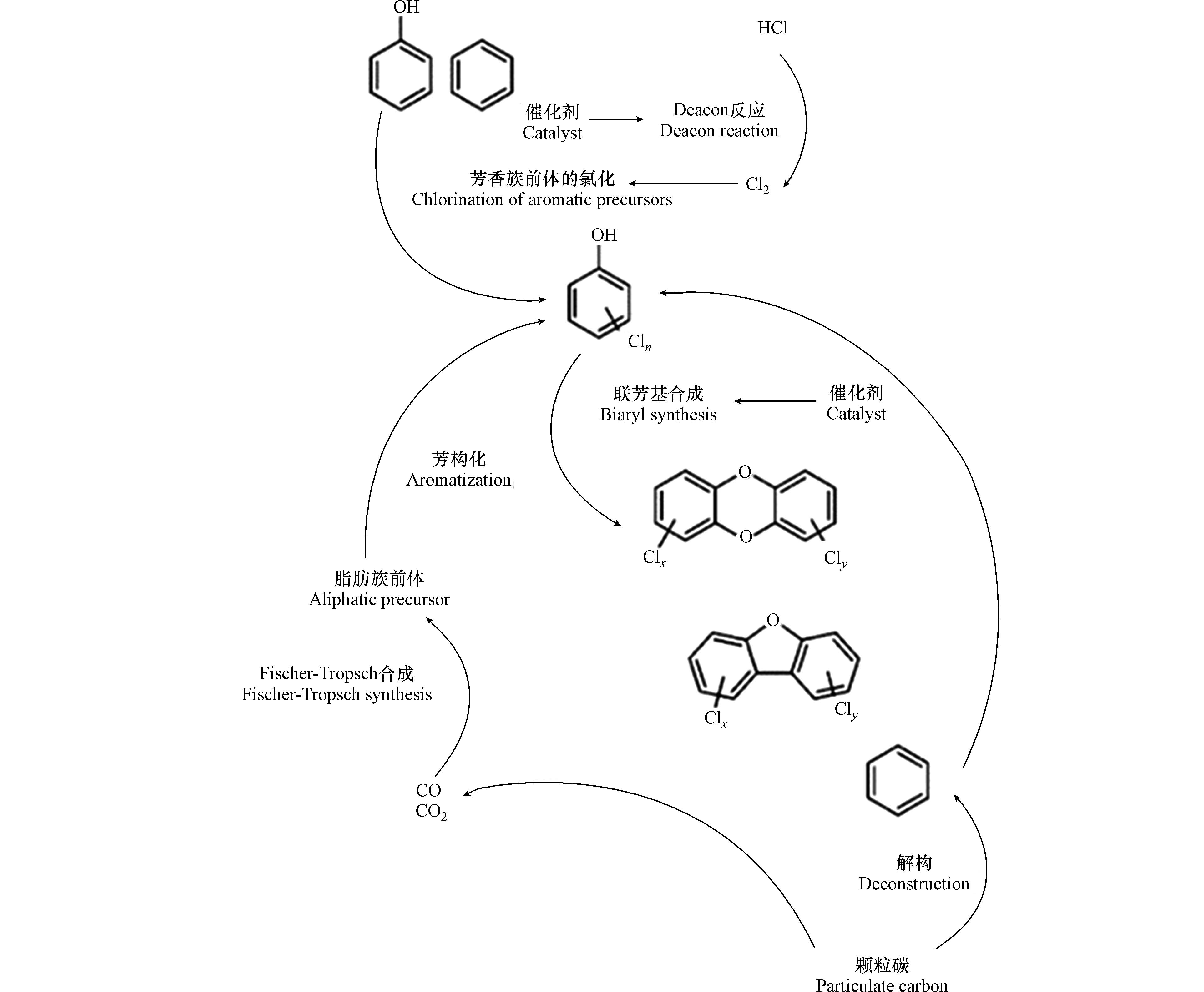

非均相反应是二噁英形成的一个关键机制[24-25],主要包括二噁英类前驱物合成[26]和从头合成[27]。前驱物合成是因为不完全焚烧和飞灰表面的非均相催化,在250—400 ℃下可形成多种有机前驱物,如多氯联苯和氯酚,这些前驱物经过一系列反应过程生成PCDD/Fs。研究表明,PCDDs与PCDFs的主要生成途径不同,Huang等[28]在实验炉中以氯酚、氯苯为前驱物,研究了它们在250—400 ℃飞灰表面的异相催化反应,发现氯酚可通过分子重排或异构,同时发生脱氯、脱氢以及分子间缩合等反应生成PCDDs。Cu、Fe等催化剂可促进氯苯和多氯联苯发生闭合反应从而生成PCDFs。从头合成反应是指碳、氢、氧和氯等元素经过氧化反应和缩合反应生成PCDD/Fs[29]。Tuppurainen等[29]根据大量文献描述了从头合成的机理,如图1所示,碳和Cu、Fe等催化剂促进了联芳基合成,最后在200—500 ℃下,通过缩合反应生成PCDD/Fs。通常情况下,前驱物反应生成的主要是PCDDs,从头合成更利于PCDFs的生成[28],因此根据PCDDs/PCDFs的比例可判断出哪种机理占优势,如当PCDDs/PCDFs>1时,前驱物反应占主导地位[30]。

均相反应主要是高温气相合成反应,即气相中氯酚(chlorophenol,CP)和氯苯(chlorobenzene,CBz)等氯代前驱物在500—800 ℃温度下进行热解重排反应生成PCDD/Fs[31]。通过图2可知,短链脂肪烃如烯烃、乙炔等在一定条件下通过氯化反应生成氯联苯,氯联苯在高温条件下会反应生成PCDD/Fs[32]。有研究认为高温气相合成反应产生的PCDD/Fs对总的PCDD/Fs贡献量较小[33]。Shaub等[34]提出了13种气相生成PCDDs的机理,最终发现,在高温燃烧过程中气相生成并不是PCDD/Fs的主要来源。

除上述外,众多学者通过理论计算和实验结果相结合来推断焚烧过程中PCDD/Fs生成机理,发现有机自由基可能是其生成的重要中间体。有学者发现[35],芳香环上的氢原子容易被气相中羟基自由基等取代生成氯代苯和氯苯酚后通过缩合反应生成PCDD/Fs。氯苯、氯酚等前驱物通过缩合反应生成自由基等中间体后发生闭环反应,再经氯化或脱氯反应,形成PCDD/Fs[36]。Li等[37]通过密度泛函理论的M06-2X-GD3方法,预测了邻苯二甲酸合成PCDDs和PCDFs的形成机理,发现了邻苯与苯基、苯氧基和苯基过氧自由基的双分子反应在放热机制下生成PCDDs和PCDFs。这些反应主要在燃烧后区域进行,在这些区域中,氧化剂不足以完全氧化有机化合物。

在此过程中发现2-苯氧基-苯基是PCDFs形成过程中的重要中间体,这是因为后续的每个基元反应都是一个快速且自发的过程。khachatryan等[38]以2-氯酚为前驱物模拟PCDD/Fs的生成,在模拟过程中检测到了苯氧自由基,同时发现了2-氯酚在金属氧化物上的化学吸附对自由基形成的影响以及氧中心自由基的空间位阻抑制了自由基-自由基反应途径,导致二苯并对二噁英(dibenzo-p-dioxin, DD)的形成。气相分子-表面结合吸附反应是形成DD的首选途径,而自由基-表面反应是形成二氯二苯并呋喃(dichloro-dibenzofuran, DCDF)的主要途径。这些结果表明,自由基-自由基表面反应的Langmuir-Hinshelwood机制和气相分子和表面结合吸附物的Eley-Rideal机制分别是PCDFs和PCDDs形成的原因。

-

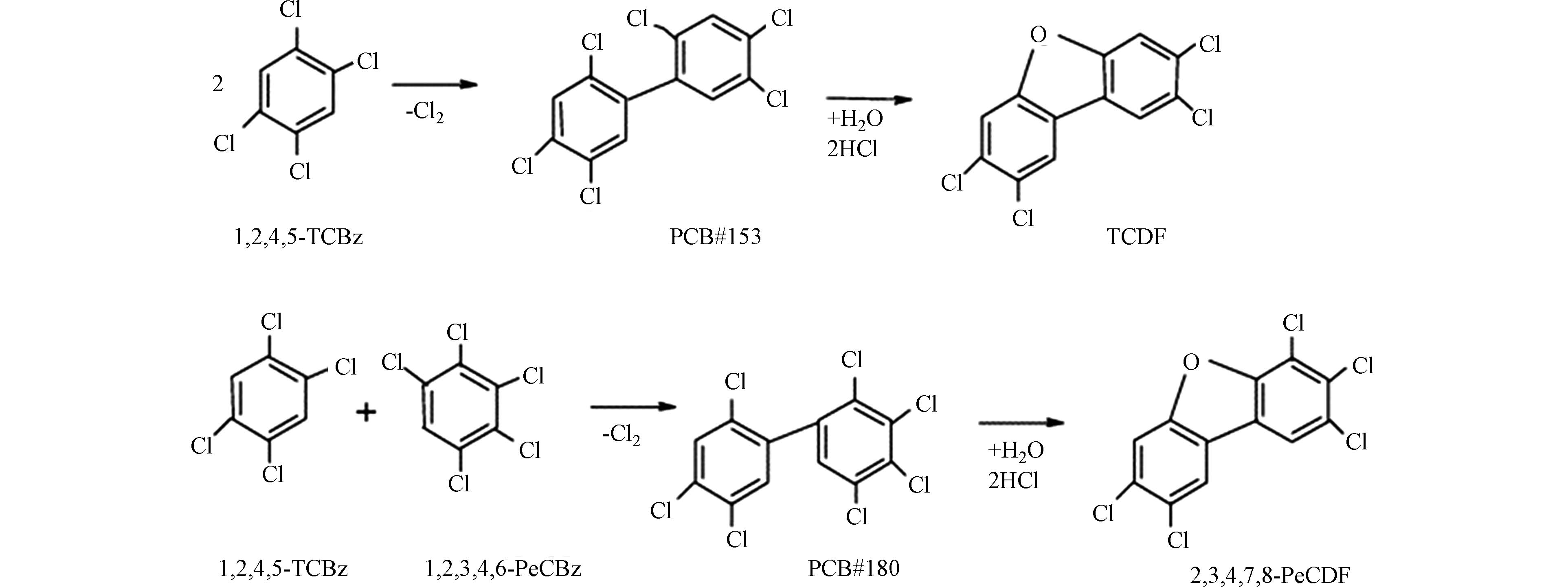

研究表明,在热工业过程中PCBs与PCDD/Fs的生成存在一定的相关性。Shin等[39]发现,PCBs的总浓度往往与飞灰中PCDD/Fs的总浓度呈正相关。Pandelova等[40]利用聚类分析等统计方法研究了木材和医疗废物混烧过程中PCBs与PCDD/Fs排放的关系,结果显示2,3,4,7,8-PeCDF与所有PCBs具有较强的相关性。因此,PCBs的形成机制与PCDD/Fs相似[41-42],主要包括从头合成和前驱体合成[43],Weber等[44]开展了实验室规模的PCBs从头合成实验,发现除氯化反应外,加氢反应也是dl-PCBs从头合成过程中的一个重要步骤。Schoonenboom等[45]研究了300—400 ℃条件下垃圾焚烧过程中PCBs的生成情况,发现在350℃时,焚烧炉灰颗粒中碳物质表面通过亲电芳香取代基团发生系列氯化反应,导致dl-PCBs生成量达到最大。Pandelova等[46]研究了实验室炉内固体废物与煤的混烧,两个氯苯自由基通过两种不同的脱氯反应聚合生成PCBs(图3)。除了上述机理中经典的反应过程外,近期研究表明自由基在PCBs的合成过程中也发挥着重要作用。有学者对两个1,2,3,5-四氯苯(1,2,3,5-tetrachlorobenzenes, 1,2,3,5-TCBz)分子通过前驱物缩合形成dl-PCBs进行研究,发现TCBz中5取代位的C-Cl键断裂后可释放氯自由基,氯自由基继而与另一个TCBz分子发生反应生成自由基中间体和Cl2分子。最终,自由基中间体之间发生反应生成3,3’,4,4’,5,5’-HxCB[47]。

-

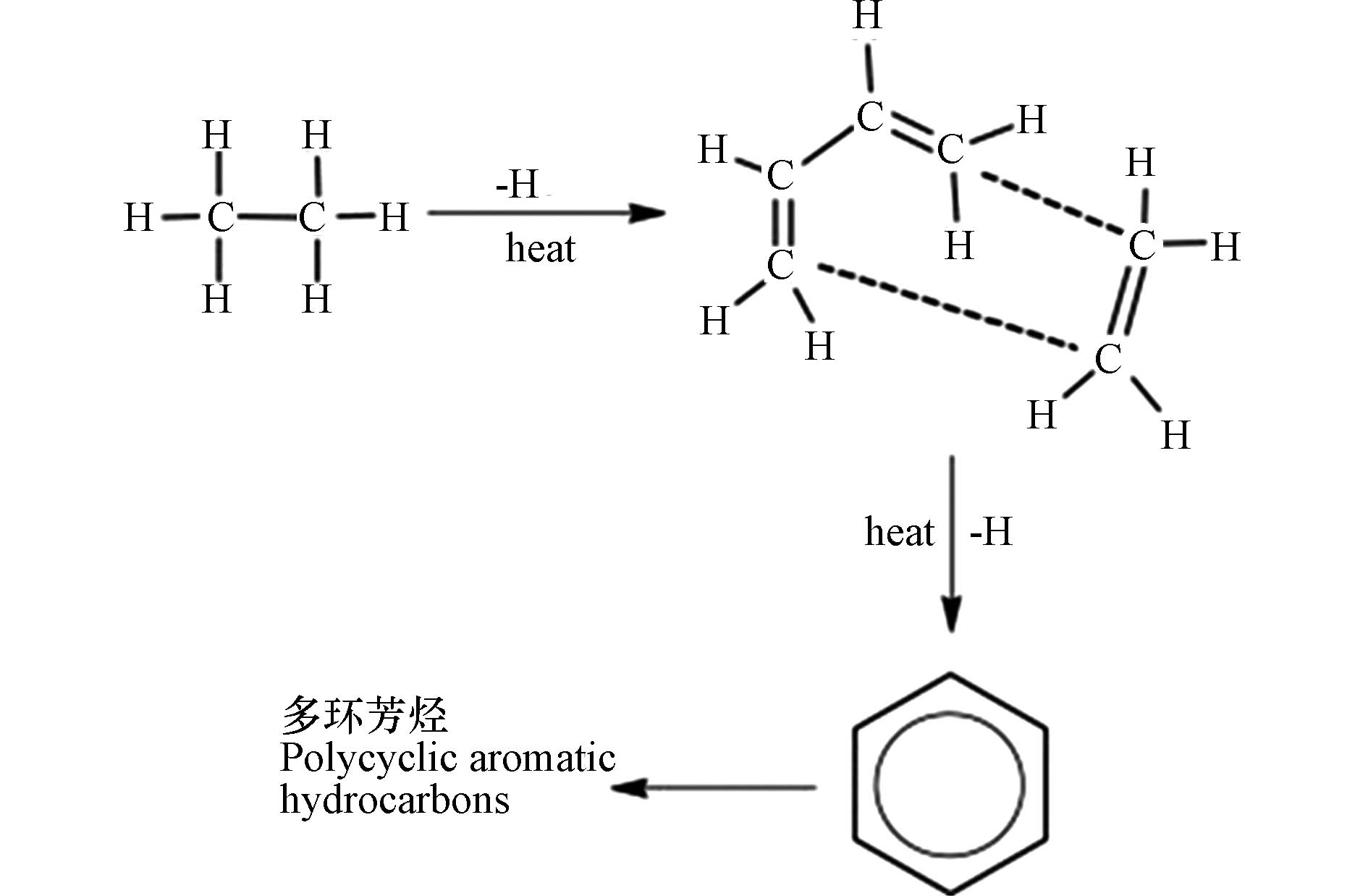

PAHs是含碳物质在不完全燃烧过程中,通过热解过程将两个或多个苯环键合成的半挥发性物质[48]。如从乙烷高温合成多环芳烃(见图4),当温度超过500 ℃时,C—H、C—C键断裂形成自由基,这些自由基聚合形成乙炔,然后进一步生成PAHs[49]。环境中PAHs来源广、数量多,目前已发现30000多种,其中具有致癌性的PAHs及其衍生物高达400多种[50]。有研究表明,PAHs主要前驱物是不饱和碳氢化合物和单环苯系物,其中2环、3环和4环PAHs主要通过氢抽取-乙炔加成机理和苯自由基加成环化机理形成,而5环和6环PAHs主要通过氢抽取-乙炔加成机理生成[51]。除此之外,PAHs的形成也与热过程中释放的有机自由基有关[52]。有研究表明,木材燃烧是大气中PAHs的主要来源[53]。Han等[54]研究了3种木材和3种煤在不同温度下焚烧产生多环芳烃的形成机理,实验结果表明木材燃烧中高温合成反应是PAHs形成的主要机制,而煤炭燃烧产生PAHs的主要来源是煤超分子结构的热解。

目前众多学者通过实验和量子化学等方法对有机污染物的生成路径进行研究。现阶段,对PCDD/Fs和PCBs的生成机理研究相对较多,但对PAHs的生成机理研究较少。为了更有效的控制有机污染物的生成,对有机污染物的形成机理需进一步研究。

-

相比其他不同种类固体废物混烧,市政污泥与生活垃圾混烧的研究较成熟。目前研究表明,市政污泥与城市生活垃圾混烧产生的PCDD/Fs浓度低于城市生活垃圾单独焚烧(表1)。

吕家扬等 [55]对南方某生活垃圾焚烧发电厂开展不同混烧比例的(0%、5%、10%和15%)市政污泥与生活垃圾协同焚烧试验,5%市政污泥组分混烧产生PCDD/Fs毒性当量最大,这可能是因为添加污泥后对应的燃烧温度也随之降低[63]。PCDD/Fs毒性当量在10%和15%市政污泥组分混烧时逐渐降低,其中15%市政污泥混烧组与生活垃圾单独焚烧组相比,PCDD/Fs的毒性当量减少了50%。这是因为随着添加污泥量逐渐增多,S元素含量也随之增多,S通过气相反应降低氯的浓度,从而阻止芳香族取代反应。陈兆明等[56]发现生活垃圾单独焚烧时,烟气中的二噁英毒性当量浓度为0.0087 ng I-TEQ·Nm−3;当混烧15%的污泥时,烟气中二噁英毒性当量浓度降低至0.0047 ng I-TEQ·m−3。为保证生活垃圾焚烧发电厂设备的蒸汽温度、保留时间等运行条件,相关研究表明半干市政污泥混烧比例应在20%以下[64]。若污泥掺入的比例过大会造成混合燃料含水率升高、热值降低,从而影响混合燃烧运行。因此,生活垃圾和污泥混烧必须保持适当的混合比例。为了探究市政污泥最优混烧比,研究学者做了大量工作。余杰等[57]发现直接混烧12.5%左右的污泥,对生活垃圾入炉量、焚烧炉稳定性及污染物排放量均未产生较大影响。陈海军等[58]分析了城市生活垃圾分别混烧5%、10%和15%的市政污泥时烟气中PCDD/Fs的排放特征,结果发现混烧比为5%时二噁英排放量为0.024 ng I-TEQ·Nm−3,在混烧比为10%时降至0.011 ng I-TEQ·Nm−3,而在15%时有所升高,达0.057 ng I-TEQ·Nm−3(表1)。严骁等[65]研究表明低于15%的污泥混烧比例不会显著提升焚烧固废中污染物排放浓度,在5%、10%和15%的污泥混烧比例下飞灰中总PCDD/Fs含量与污泥混烧比例呈负相关,可能与污泥的引入改变了投料中S、Cl质量分数有关,其中SO2的增加抑制了Cu的催化活性,导致PCDD/Fs含量降低。综上所述,将污泥与生活垃圾按一定比例掺混入炉焚烧,可降低有机污染物浓度,这可能是由于污泥中S元素含量较高,Cl含量相对较低,从而减少了PCDD/Fs的合成[66]。

-

在固体废物中,除市政污泥外,木材、塑料、纺织品等均有较高热值,为了更好的利用有机固废的热值,实现固废减量化,众多学者对木材与城市生活垃圾混烧也做了大量研究。Edo等[59]研究了商业白木(ST)和建筑木材(DC)分别与城市生活垃圾在小型实验装置上焚烧产生PCDD/Fs、PCBs和PAHs的浓度水平(表1)。生活垃圾与DC混烧产生PCDD/Fs和PCBs的浓度高于其与ST混烧产生的浓度,这是因为DC中Cl元素含量高会促进PCDD/Fs和PCBs形成[67]。然而相比DC,ST与生活垃圾混烧时PAHs生成量更高,浓度为(32±3.8)mg·kg−1,这是因为ST的燃烧效率低于DC。研究发现较低含量的湿垃圾(1%—4%)混烧对有机污染物的形成没有明显影响,但湿垃圾含量较高时会促进PCDD/Fs的生成。Evensson等 [60]分析了回收木材(RW)单独焚烧时烟气中PCDD/Fs浓度为22.6 ng·m−3,RW与城市生活垃圾在75:25的比例下分别与湿垃圾含量在20%—25%和45%的城市生活垃圾混烧,生成的烟气中PCDD/Fs浓度分别为14.6 ng·m−3和23.9 ng·m−3。湿垃圾含量为20%—25%的城市生活垃圾混烧产生的PCDD/Fs浓度最低,同时其与RW混烧产生的PCDFs几乎比RW与湿垃圾含量较高的城市生活垃圾混烧时低50%,但PCDDs浓度的差异不太明显。由于Cl元素的产生与湿垃圾含量有关,所以湿垃圾含量较高的固体废物混烧产生的PCDD/Fs浓度高。Tomsej等[61]在家用锅炉中将聚乙烯(PE)和聚对苯二甲酸乙二醇酯(PET)两种购物袋分别与木材燃烧发现,7种致癌多环芳烃(c-PAHs)的毒性当量增加,其中木材和PET焚烧过程中c-PAHs毒性当量增加高达90%(表1),因此在家用锅炉中应避免PET焚烧。Maasikmets等[53]发现木材、纸张和生活垃圾在取暖炉中混烧产生的PCDD/Fs平均浓度高于垃圾焚烧厂,这是由于取暖器燃烧含氧量少,容易发生不完全焚烧,因此,应该避免在取暖器中焚烧生活垃圾。Moreno等[68]在传统家用炉中将家具木材与10%的聚氨酯泡沫的混合物焚烧,结果表明混烧有助于减少PAHs、挥发性和半挥发性化合物的生成,对PCDD/Fs有轻微抑制作用。同时在850℃的实验室规模反应器中将废弃的家具木材与实木(未经处理木材)分别焚烧后,发现废弃的家具木材产生的PCDD/Fs浓度较低。这可能是由于家具木材中含有氮化胶粘剂、阻燃剂等,抑制了PCDD/Fs的形成。在实验室反应器中,PCDD/Fs的分布以PCDFs为主,而在住宅炉中,由于操作条件的不同,PCDD/Fs的分布以PCDDs为主。综上所述,在含有大量Cl和过渡金属元素的木材焚烧时会促进PCDD/Fs和PCBs的生成。

-

除了市政污泥、木材外,在其他固体废物与城市生活垃圾混烧方面也有一定的研究。Cai等[62]通过对填埋材料垃圾衍生燃料(LMRDF)(塑料、橡胶、木材)与RDF焚烧的研究,发现烟气中PCDD/Fs毒性当量随着LMRDF混烧比的增加而降低(表1)。当LMRDF混烧比为30%、炉温为850℃时,PCDD/Fs毒性当量降低至(0.71±0.47)ng I-TEQ·m−3。然而在混烧比与炉温相同的情况下,干燥的LMRDF混烧时产生的PCDD/Fs毒性当量最小,为(0.63±0.26)ng I-TEQ·m−3。LMRDF的混烧增加了飞灰中的PCDD/Fs浓度,尤其是干燥的LMRDF,且较高的温度会减少飞灰中PCDD/Fs的毒性当量,这是因为飞灰中的PCDD/Fs主要通过低温非均相合成。对比烟气和飞灰中PCDDs和PCDFs的比例发现,PCDFs/PCDDs的比例均大于1,表面从头合成可能是形成PCDD/Fs的主要方式。

目前对不同种类固体废物混烧过程中有机污染物的形成机理研究较少,但在固废与煤混烧方面的研究相对成熟,如Chen等[69]将模拟的城市固体垃圾与不同混烧比例(0%、7.5%、15%、20%和25%)的煤在管式炉中共燃,结果表明,飞灰中PCDD/Fs的形成途径随着城市生活垃圾比例的增加,由氯酚等前驱物合成转变为从头合成,这是因为煤中丰富的碳源促进了碳基质和PAHs的生成,且Cl和金属元素含量的增加又极大地促进了这一过程。煤与固体废物的混烧可能会导致有机污染物主要生成途径发生改变,但是目前不同种类固废混烧对于有机污染物的形成途径是否会发生改变尚不清楚。

综上所述,影响固体废物混烧中有机污染物的生成因素主要有固废类型、混烧比例以及温度等燃烧条件。这些条件的不同导致有机污染物浓度及其毒性当量存在差异,这是因为不同种类固废混合后其热值、含水率、固废元素组成(Cl、C、S、N等)等因素会发生改变,如市政污泥与城市生活垃圾混合后含水率增多,S、N等元素增多;木材与城市生活垃圾混合,C元素会增加,但木材中可能会含有Cl、Cu等元素,这些元素会影响有机污染物的生成。除此之外在混烧过程中会产生一些金属催化剂,会促进有机污染物的生成,也可能改变有机污染物的主要生成途径。在我国提倡清洁生产的大背景下,依据国家法律,拓展不同种类固体废物间的混烧,可达到节约能源、减少污染物排放等目的。不同种类固废混烧与城市生活垃圾单独焚烧产生有机污染物的机理相似,但是,由于混烧的固废不同,各个元素含量不同,因此可能会导致主要生成途径发生变化。目前针对混烧过程中有机污染物的生成机理及影响因素还需要进一步深入研究。

-

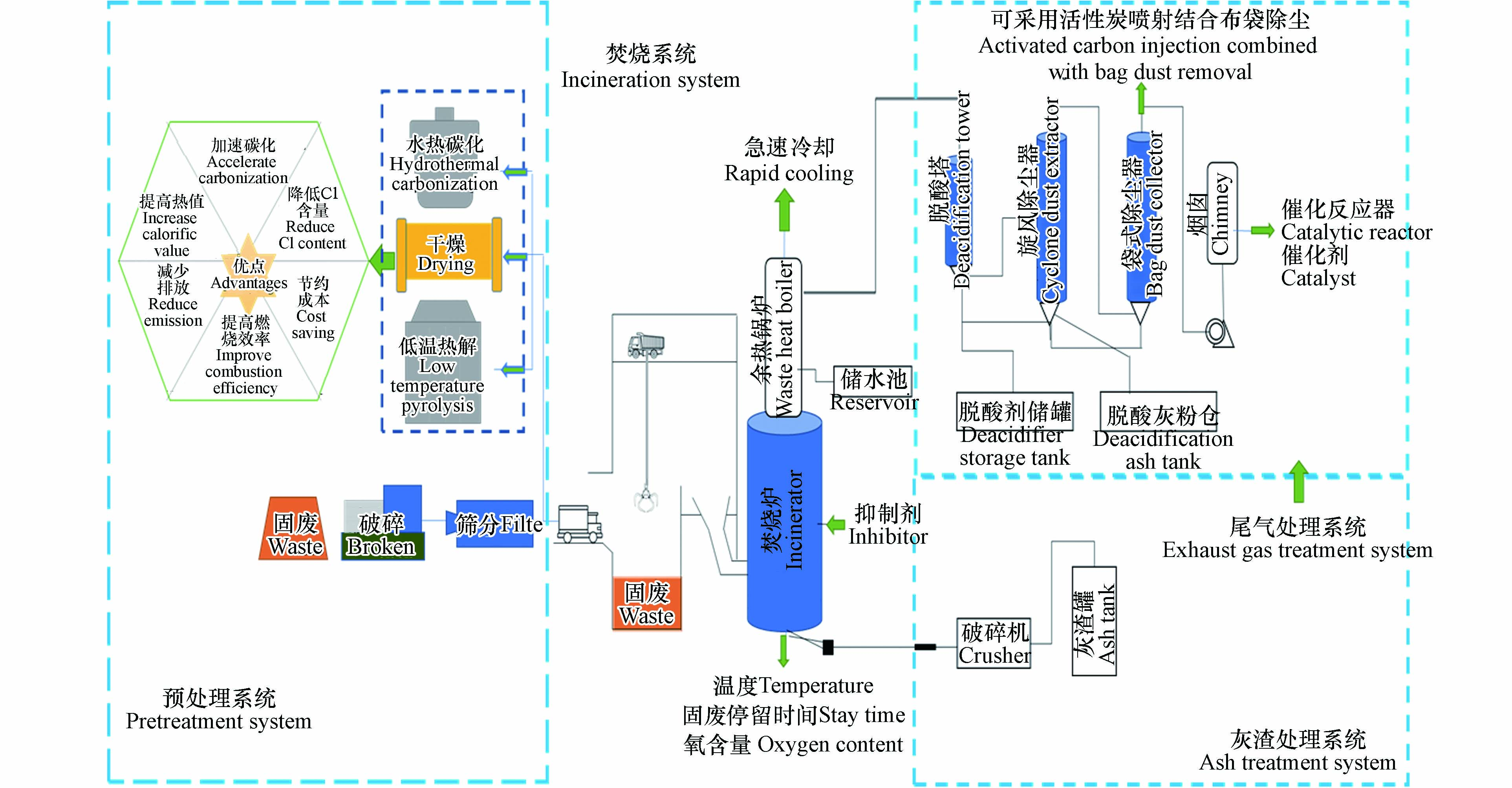

随着研究的不断深入,不少学者发现可以通过改进预处理系统、焚烧系统和烟气处理系统来减少有机污染物的产生。基于垃圾焚烧的工艺条件及有机污染物的生成机理,改变固废性质、燃烧条件、加入抑制剂以及末端控制等方法控制有机污染物的产生,其中末端控制应用较为广泛(图5)。

-

除了传统的压实、分选、破碎等方法外,还可以采用干燥、水热碳化、低温热解等方法对固废进行预处理,也可以通过添加煤等物质来增加固废热值。对于含水率高的城市生活垃圾,可以对其进行干燥,加速其碳化,提高热值和燃烧效率,也可降低发电厂城市生活垃圾运输、处理及减排成本[52]。水热碳化可以提高固废碳化程度,由于水热碳化过程简单,可省略耗能大的干燥过程,且可减少污染物的产生,因此它被认为是最有效最有前途的城市生活垃圾热化学升级技术之一[70]。Lin等 [71]研究表明,水热碳化大幅度的提升了废木材和湿垃圾的碳化。此外,通过对城市生活垃圾进行低温热解,可以增加固废热值,降低固废中的Cl含量,减少运输和储存成本[72-73],同时也能降低有机污染物的生成浓度。Saeed等[74]对PVC、PVC-木材、PVC-煤混合物进行了两段流化床热解焚烧实验,结果表明,焚烧前的热解过程有助于去除PVC中的Cl元素,降低PCDD/Fs形成的风险。固体废物的热值很大程度上影响了有机污染物的生成,Peng等[75]分析城市生活垃圾与煤在800℃混烧时,烟气中PAHs的实验值与理论值相差约10倍,因此煤与生活垃圾混烧存在显著的协同作用,能够抑制多环芳烃的形成,特别是剧毒高环多环芳烃。

-

在焚烧过程中,可通过改变焚烧工艺参数(“3T+E”)来控制有机污染物生成。目前对于焚烧过程中燃烧条件(温度、停留时间、含氧量)的研究已十分成熟(图5)。除此之外,为了减少PCDD/Fs的排放,也可在焚烧过程中喷入抑制剂。截至目前,抑制PCDD/Fs生成的抑制剂大概有三类:(1)含N化合物,氨、乙醇胺、乙二胺四乙酸、二乙醇胺、单乙醇胺等[76];(2)含S化合物,硫代硫酸钠、单质硫、三氧化二硫、黄铁矿、高硫煤等[77-78];(3)含S和N化合物,硫脲、硫代硫酸铵、氨基磺酸等[79]。这类化合物多为碱性,可以与氯代化合物发生反应,从而生成氨类、氰化物等物质,起到抑制二噁英生成的作用[80]。

有研究表明,含有S和N的化合物作为燃料添加剂时,PCDD/Fs浓度显著降低[81]。Chang等 [77]研究表明,在工业废弃物中加入硫化物可以有效降低垃圾焚烧过程中PCDD/Fs的生成。当S/Cl摩尔比为0.5、1、2和3时,对PCDD/Fs的抑制作用分别为32%、44%、54%和30%,由此可知,在燃烧过程中加入过多的S不能有效减少PCDD/Fs的形成,有时甚至会增加PCDD/Fs和颗粒物的排放。因此,在垃圾焚烧过程中加入适量的抑制剂对抑制PCDD/Fs的形成至关重要。此外,CaO在流化床燃烧中有着广泛应用。Liu等[82]发现使用CaO在开放和封闭体系中对PCDD/Fs有明显的抑制作用,抑制率分别超过99%和90%。Li等[83]研究发现CaO/尿素混合反应体系中形成的2,3,7,8-PCDD/Fs的毒性当量均低于尿素或CaO单独反应体系,特别是在尿素占比为5%—20%的混合反应体系中PCDD/Fs的抑制效率始终接近100%,这可能是因为混合抑制剂与五氯苯酚生成多种中间体,从而抑制了PCDD/Fs的形成。Ma等[84]研究发现S/CaO混合抑制剂的添加可以分解PCDD/Fs或其前驱物,也可通过与含Cl化合物反应,从而减弱PCDD/Fs形成中的氯化过程,抑制PCDD/Fs的形成,其中对六氯代和七氯代二噁英的抑制作用最为显著。即使添加S和CaO等抑制剂,PCDD/Fs的主要生成途径也保持不变。Chen等[85]使用硫脲作为PCDD/Fs的抑制剂,并对其抑制机理进行了详细研究,发现在燃烧后区域,PCDD/Fs的形成路径依次为:从头合成>氯酚合成>氯化氧芴和二苯并二氧杂苯。硫脲中的S和N抑制了金属催化剂,因此对从头合成的抑制作用大于氯酚合成的抑制作用。Lundin等[86]在焚烧树皮、木屑、碎料和废纸时添加硫酸铵,发现PCDD/Fs和PCBs的氯化被抑制,从而也降低了其同系物(四氯到八氯)的浓度。

目前对PCDD/Fs的抑制剂研究较成熟,但对PCBs和PAHs的抑制剂研究较少。部分学者发现,硅铝复合添加剂[87]和Mg(OH)2[88]等化合物可以抑制PCBs的生成。硫酸锰[89]、铂和钯[90]、Rh/Al2O3和Rh–Na/Al2O3[91]等可以作为PAHs的抑制剂。由于PCDD/Fs与PCBs不仅具有相似的物理和化学性质,其生成途径也有一定相关性[92],因此,PCDD/Fs的抑制剂也可用于抑制PCBs的生成,以此达到减少有机污染物排放的目的。

-

末端控制主要包含吸附和催化分解。实际应用中,多采用活性炭喷射结合布袋除尘的组合(ACI+BF)来控制烟气中有机污染物的排放[93-94]。Chi等[93]考察了大型城市生活垃圾焚烧炉和工业垃圾焚烧炉ACI+BF工艺对尾部烟气的处理情况,结果显示该技术可同时脱除气相和固相的PCDD/Fs。ACI+BF技术对PCDD/Fs的脱除效率可以高达96%,被认为是脱除PCDD/Fs最有效的方法[95]。

相比吸附技术,催化分解技术更加稳定、对污染物的去除更为彻底。国内外的实际案例表明催化分解技术最有可能替代吸附技术去除难降解有机污染物[96]。目前降解PCDD/Fs、氯苯等有机污染物的催化剂可根据其活性组分分为贵金属[97]和过渡金属氧化物[98]。通常,贵金属催化剂的活性较好,但它们在催化燃烧过程中容易失活中毒。此外,贵金属资源稀少、价格昂贵,很难在实际工况中大规模推广应用。与贵金属催化剂相比,过渡金属氧化物具有较好的热稳定性和抗氯中毒能力,容易获取,目前已得到广泛的应用[99]。过渡金属氧化物催化剂主要有钛基、铈基、锰基、铈钛基等。目前,已被商业化使用的催化剂有V2O5(-WO3)/TiO2、V2O5-MoO3/TiO2等,蒋威宇[100]研究了V2O5-WO3/TiO2商业催化剂协同净化NOx和氯苯的反应性能,在300°C反应条件下,催化剂可同时稳定地转化NOx和氯苯,转化率分别为90%和100%,而在200℃时,发现催化剂失活中毒。当SO2存在时,反应环境的碱性被削弱,二氯苯转化为氯苯酚受阻,二噁英类物质生成量下降。过渡金属催化剂还可以与反应器相结合,如壳牌推出的SDDS系统,其主要是由一个横向流反应器和V2O5/TiO2催化剂组成,可降解PCDD/Fs、PCBs和PAHs等有机污染物,在150℃时,PCDD/Fs脱除效率达98%以上[101]。商业催化剂虽已被广泛使用,但存在起燃温度高、比表面积低等缺点[102]。为了寻找性能更加优异的催化剂,众多学者在实验条件下进行了诸多探索。杜翠翠[103]使用球磨法制备VOx/TiO2催化剂,其对PCDD/Fs降解效率达97%以上。罗邯予[104]研究表明10%Mn/Ce0.3Ti0.7O2和3DOM Ce0.3Ti0.7O2催化剂均具有良好的活性和稳定性,在330℃反应14 h对氯苯的转化率基本稳定在90%和100%。然而目前在低温条件下催化剂存在活性较差、对污染物降解效率低的问题。因此,如何提升催化剂低温活性成为了当今研究热点。目前控制有机污染物生成的手段多,但在实际应用中较单一,为了更高效地降解有机污染物浓度,过程控制往往要与末端控制相结合。

-

本文全面概述了固体废物焚烧过程中有机污染物的生成机理,并对不同种类城市固废混烧产生的有机污染物排放特征及机理进行了探究。近年来研究不同种类固体废物混烧的主要对象有市政污泥与生活垃圾、木材与城市固废、塑料与城市固废等。不同固废类型、混烧比例会导致其热值、含水率、固废元素组成(Cl、C、S、N等)等发生改变,从而影响有机污染物的生成。城市生活垃圾中Cl和金属元素含量较高会促进有机污染物的生成,而S和N元素则会抑制Cu等金属的催化活性,导致有机污染物含量降低。

为了控制焚烧产生的有机污染物,除了传统手段“3T+E”外,还可以通过对固体废物预处理、添加抑制剂及末端处置等方法来控制有机污染物的生成。固废预处理主要改变其含水率高、热值低等问题。焚烧系统中可加入抑制剂来减少有机污染物的生成,抑制PCDD/Fs生成的抑制剂主要是碱性化合物,包括含N化合物、含S化合物、含S/N化合物。硅铝复合添加剂和Mg(OH)2等化合物可以抑制PCBs的生成,此外PCDD/Fs的抑制剂也可用于抑制PCBs的生成。硫酸锰、铂和钯、Rh/Al2O3和Rh–Na/Al2O3等可以作为PAHs的抑制剂。末端控制主要包含吸附和催化分解,与吸附技术相比,催化分解技术更加稳定、去除效率更高,但是目前催化剂在低温条件下的活性偏低。因此,如何提升催化剂低温活性成为现阶段的研究热点。

通过对相关研究进行总结,今后可从以下几个方面开展研究工作:(1)现阶段对于PCDD/Fs的生成机理研究较多,而对于其他有机污染物如PCBs、PAHs等研究较少,应开展相关研究;(2)由于焚烧产生有机污染物的影响因素较多,且通过焚烧炉探讨生成机理相对困难,因此可将实验模拟和理论计算相结合来验证有机污染物的生成机理,以便更有效的控制有机污染物的生成;(3)目前对于不同固体废物混烧产生有机污染物的排放水平及机理研究相对较少,为了有效减少固体废物的数量和毒性,实现能源的高效回收,应对其展开深入研究;(4)目前为了更加有效的降低有机污染物的生成,应结合有机污染物的生成机理,对预处理、焚烧系统及末端控制进行优化改善,并将过程控制与末端控制结合。

城市生活垃圾与工业有机固废协同处置中有机污染物生成特征及控制技术

Generation characteristics and control technology of organic pollutants during the co-combustion of municipal solid waste and industrial organic solid waste

-

摘要: 近年来固体废物产生量日益增多,而多种固体废物协同处置能够提高生活垃圾热值,实现固体废物的有效减容。为了有效减少有机污染物的排放,本文对在焚烧过程中二噁英、多氯联苯和多环芳烃的形成机理进行了探究,并着重阐明了不同固废(市政污泥与生活垃圾、木材与生活垃圾等)混烧产生有机污染物的排放特征以及关键影响因素。研究结果表明,固废种类、添加比例、组分、含水率等能够影响有机污染物的生成。较高的Cl和金属元素会促进有机污染物的生成,而S和N元素则有抑制效应。根据垃圾焚烧的工艺条件及有机污染物的生成机理,发现除“3T+E”外,改变固废性质、加入抑制剂及末端处置等方法也能有效控制有机污染物的产生。通过预处理可降低固废含水率提高热值。焚烧系统中可加入碱性化合物、硅铝复合添加剂、Mg(OH)2、硫酸锰、铂和钯等抑制剂来减少PCDD/Fs、PCBs和PAHs等有机污染物的生成。末端控制主要包含吸附和催化分解,其中催化分解技术更加稳定、去除效率更高,但目前催化剂的低温活性还有待进一步提高。整体来看,在清洁生产的大背景下,拓展不同种类固体废物间的混烧,可达到节约能源、减少污染物排放等目的,但不同固废混烧过程中有机污染物生成特征变化及控制机理还需进一步深入研究。Abstract: In recent years, the amount of solid wastes generated has been increasing, and the co-combustion of multiple solid wastes can increase the calorific value of domestic wastes and achieve effective volume reduction of solid wastes. In order to effectively reduce the emission of organic pollutants, this paper explores the formation mechanism of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzodurans (PCDD/Fs), polychlorinated biphenyl (PCBs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAHs) during the incineration, and focuses on the emission characteristics and key influencing factors of organic pollutants during the co-combustion of solid wastes (municipal sludge and municipal solid wastes, woods and municipal solid wastes, etc.). The type of solid wastes, addition ratio, composition, moisture content, etc. can affect the generation of organic pollutants. Higher levels of Cl and metal elements promote the formation of organic pollutants, while S and N elements have an inhibitory effect. According to the process conditions of waste incineration and the formation mechanism of organic pollutants, it has been found that in addition to "3T+E", methods such as changing the nature of solid wastes, adding inhibitors and terminal control can also effectively control the generation of organic pollutants. The moisture content of solid wastes can be reduced and the heating value can be increased through pretreatment. Alkaline compounds, silicon-aluminum composite additives, Mg(OH)2, manganese sulfate, platinum and palladium and other inhibitors can be added in the incineration system to reduce the generation of organic pollutants, such as PCDD/Fs, PCBs and PAHs. The control technology mainly includes adsorption and catalytic decomposition. The catalytic decomposition technology is more stable and the removal efficiency is higher. However, the low temperature activity of the current catalyst needs to be further improved. Overall, under the background of cleaner production, expanding the co-combustion of different types of solid wastes can achieve the goals of saving energy and reducing emissions of pollutants. However, the formation characteristics and control mechanism of organic pollutants during the co-combustion needs to be further studied.

-

Key words:

- solid waste /

- co-combustion /

- organic pollutants /

- control technology

-

-

表 1 不同固废在不同混烧比下的产物类型与浓度

Table 1. Sample types and concentrations of different solid wastes at different co-combustion ratios

固废类型

Types of solid waste温度

Temperature混烧比

Co-combustion

ratios有机物

Organic产物

Sample浓度/毒性当量

Concentration/TEQ文献

Reference生活垃圾 983—1010℃ — PCDD/Fs 炉渣 0.8 ng I-TEQ·kg−1 [55] 生活垃圾、市政污泥 5%市政污泥 1.2 ng I-TEQ·kg−1 10%市政污泥 0.5 ng I-TEQ·kg−1 15%市政污泥 0.4 ng I-TEQ·kg−1 生活垃圾 — PCDD/Fs 飞灰 1129.5 ng I-TEQ·kg−1 生活垃圾、市政污泥 5%市政污泥 1157.2 ng I-TEQ·kg−1 10%市政污泥 973.4 ng I-TEQ·kg−1 15%市政污泥 684.2 ng I-TEQ·kg−1 生活垃圾 860℃ — PCDD/Fs 烟气 0. 0087 ng I-TEQ·m−3 [56] 生活垃圾、市政污泥 15%市政污泥 0. 0047 ng I-TEQ·m−3 生活垃圾 950℃ — PCDD/Fs 烟气 [57] 生活垃圾、市政污泥 12.5%市政污泥 0.0137 ng I-TEQ·m−3 生活垃圾、市政污泥 — 5%市政污泥 PCDD/Fs 烟气 0.024 ng I-TEQ·m−3 [58] 生活垃圾、市政污泥 10%市政污泥 0.011 ng I-TEQ·m−3 生活垃圾、市政污泥 15%市政污泥 0.057 ng I-TEQ·m−3 ST 220—380℃ — PAHs 飞灰 9.6 mg·kg−1 [59] ST、生活垃圾 20%生活垃圾 (32±3.8) mg·kg−1 DC、生活垃圾 20%生活垃圾 (6.4±1.9)mg·kg−1 ST — PCBs 7.2 μg·kg−1 DC 220—380℃ — PCBs 飞灰 (10.6±2.4) μg·kg−1 [59] ST、生活垃圾 20%生活垃圾 (0.28±0.02)(WHO-TEQ) ng·kg−1 DC、生活垃圾 20%生活垃圾 (9.6±4.5)(WHO-TEQ) ng·kg−1 RW 140℃ — PCDD/Fs 烟气 22.6 ng·m−3 [60] RW、生活垃圾(含水量20%—25%) 25%生活垃圾 14.6 ng·m−3 RW、生活垃圾(含水量45%) 23.9 ng·m−3 榉木 — — PAHs (1.0±0.2) mg·kg−1 [61] 榉木、PET 7% PET (1.9±0.3) mg·kg−1 榉木、PE 7% PE (1.1±0.1) mg·kg−1 LMRDF 850℃ — PCDD/Fs 烟气 (3.54±0.94) ng I-TEQ·m−3 [62] RDF1 — (1.86±0.86) ng I-TEQ·m−3 RDF2 — (1.28±0.73) ng I-TEQ·m−3 LMRDF、RDF1 10% RDF1 (2.90±0.78 )ng I-TEQ·m−3 LMRDF、RDF1 20% RDF1 (2.54±1.24 )ng I-TEQ·m−3 LMRDF、RDF1 30% RDF1 (0.71±0.47) ng I-TEQ·m−3 LMRDF、RDF1 30%干燥的RDF1 (0.63±0.26 )ng I-TEQ·m−3 LMRDF、RDF1 750℃ 30% RDF1 (1.66±0.66) ng I-TEQ·m−3 LMRDF、RDF1 950℃ 30% RDF1 (5.20±1.56) ng I-TEQ·m−3 LMRDF 850℃ — 飞灰 (180.87±18.82) ng I-TEQ·kg−1 RDF1 — (7.50± 0.75 )ng I-TEQ·kg−1 RDF2 — (109.10±6.85 )ng I-TEQ·kg−1 LMRDF、RDF1 10% RDF1 (16.67±1.98) ng I-TEQ·kg−1 LMRDF、RDF1 20% RDF1 (31.89±3.62) ng I-TEQ·kg−1 LMRDF、RDF1 30% RDF1 (18.31±1.76 )ng I-TEQ·kg−1 LMRDF、RDF1 30%干燥的RDF1 (65.22±7.42 )ng I-TEQ·kg−1 LMRDF、RDF1 750℃ 30% RDF1 (59.43±6.72 )ng I-TEQ·kg−1 LMRDF、RDF1 950℃ 30% RDF1 (19.86±2.06 )ng I-TEQ·kg−1 注:LMRDF:填埋材料垃圾衍生燃料;RDF1:来自临子焚烧厂的垃圾衍生燃料;RDF2:吉林申飞环保能源有限公司的垃圾衍生燃料;ST:商业白木;DC:建筑木材;PET:聚乙烯与苯二甲酸酯瓶;PE:超市聚乙烯购物袋.

Note: LMRDF: landfill material refuse-derived fuel, RDF1: the experiment were collected from the Linzi incineration plant, RDF2: Jilin Shenfei Environmental Protection Energy, ST: commercial stemwood, DC: demolition and construction waste wood, PET: polyethylene terephthalate bottles, PE: supermarket polyethylene shopping bags. -

[1] KANHAR A H, CHEN S Q, WANG F. Incineration fly ash and its treatment to possible utilization: A review [J]. Energies, 2020, 13(24): 6681. doi: 10.3390/en13246681 [2] GU T B, YIN C G, MA W C, et al. Municipal solid waste incineration in a packed bed: A comprehensive modeling study with experimental validation [J]. Applied Energy, 2019, 247: 127-139. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.04.014 [3] 国家统计局. 中国统计年鉴[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社. 2007-2019. National Bureau of Statistics of China. China statistical yearbook[M]. Beijing: China Statistics Press, 2007-2019(in Chinese)

[4] ZHANG Z G, YANG F, LIU J C, et al. Eco-friendly high strength, high ductility engineered cementitious composites (ECC) with substitution of fly ash by rice husk ash [J]. Cement and Concrete Research, 2020, 137: 106200. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106200 [5] REN M H, LV Z Y, XU L, et al. Partitioning and removal behaviors of PCDD/Fs, PCBs and PCNs in a modern municipal solid waste incineration system [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 735: 139134. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139134 [6] LUO H W, CHENG Y, HE D Q, et al. Review of leaching behavior of municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ash [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 668: 90-103. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.004 [7] 毛庚仁, 张涌新, 文雯, 等. 我国城市生活垃圾处理现状及焚烧法的可行性分析 [J]. 城市发展研究, 2010, 17(9): 12-16. MAO G R, ZHANG Y X, WEN W, et al. Analysis of municipal solid waste treatment status and the feasibility of incineration in China [J]. Urban Studies, 2010, 17(9): 12-16(in Chinese).

[8] LU J W, ZHANG S K, HAI J, et al. Status and perspectives of municipal solid waste incineration in China: A comparison with developed regions [J]. Waste Management, 2017, 69: 170-186. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.04.014 [9] 李诗媛, 别如山. 城市生活垃圾焚烧过程中二次污染物的生成与控制 [J]. 环境污染治理技术与设备, 2003(3): 63-67. LI S Y, BIE R S. Formation and control method of secondary pollutants from incineration of municipal solid waste [J]. Techniques and Equipment for Environmental Pollution Control, 2003(3): 63-67(in Chinese).

[10] 宋春莲. 多氯联苯/二恶英类化学污染物的环境行为及对人体健康的危害 [J]. 佳木斯大学学报(自然科学版), 2007, 25(2): 207-209. SONG C L. The environmental behavior of chemical contamination of polychlorinated biphenyl/ddioxi and the harm to human body [J]. Journal of Jiamusi University (Natural Science Edition), 2007, 25(2): 207-209(in Chinese).

[11] 于晓丽, 张江. 多环芳烃污染与防治对策 [J]. 油气田环境保护, 1996(4): 53-56. YU X L, ZHANG J. Pollution by multiring aromatic hydrocarbon and its preventive treatment strategy [J]. Environmental Protection of Oil & Gas Fields, 1996(4): 53-56(in Chinese).

[12] LIU G R, CAI Z W, ZHENG M H. Sources of unintentionally produced polychlorinated naphthalenes [J]. Chemosphere, 2014, 94: 1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.09.021 [13] ZHU F, LI X F, LU J W, et al. Emission characteristics of PCDD/Fs in stack gas from municipal solid waste incineration plants in Northern China [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 200: 23-29. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.02.092 [14] 郭颖. 固废处置中持久性自由基/二恶英的排放特性及检测研究[D]. 杭州: 浙江大学, 2014. GUO Y. Study on emission characteristics and detection of PCDD/fs and environment persistent free radicals during solid waste disposal[D]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2014(in Chinese).

[15] 张怀强. 医疗废物组分特性及其焚烧二噁英控制[D]. 杭州: 浙江大学, 2011. ZHANG H Q. Physical characteristics and dioxin emission control in medical wastes incineration[D]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2011(in Chinese).

[16] 刘劲松. 浙江省典型地区环境中持久性有机污染物污染现状, 分布规律和来源解析[D]. 杭州: 浙江大学, 2008. LIU J S. Level, distribution, and source resolution of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in typical area in Zhejiang[D]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2011(in Chinese).

[17] 李煜. 我国城市生活垃圾焚烧处理发展分析 [J]. 中国环保产业, 2014(7): 36-38. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-5377.2014.07.009 LI Y. Developing analysis on incineration treatment of urban domestic refuse in China [J]. China Environmental Protection Industry, 2014(7): 36-38(in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-5377.2014.07.009

[18] 戴勇, 余婷. 某生活垃圾焚烧厂掺烧一般工业有机固废烟气净化的应用 [J]. 机电工程技术, 2021, 50(4): 238-242. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-9492.2021.04.066 DAI Y, YU T. Application of co-processing general industrial organic solid waste flue gas purification in a municipal waste incineration plant [J]. Mechanical & Electrical Engineering Technology, 2021, 50(4): 238-242(in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-9492.2021.04.066

[19] 中华人民共和国生态环境部. 国家危废豁免清单名录(2021版)[EB/OL]. [2020-11-25]. http://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk02/202011/t20201127_810202.html. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. List of State Impervious Waste Exemptions(2021)[EB/OL]. [2020-11-25] . http://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk02/202011/t20201127_810202.html.

[20] 中华人民共和国生态环境部. 生活垃圾焚烧污染控制标准[EB/OL]. [2014-07-01]. http://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/gthw/gtfwwrkzbz/201405/t20140530_276307. shtml. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Standards for Pollution Control of Domestic Waste Incineration [EB/OL]. [2014-07-01]. http://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/gthw/gtfwwrkzbz/201405/t20140530_276307.shtml.

[21] 董晓丹, 张玉林. 上海市生活垃圾理化特性调查分析 [J]. 环境卫生工程, 2016, 24(6): 18-21. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-8206.2016.06.006 DONG X D, ZHANG Y L. Investigation and analysis of physicochemical characteristics of municipal solid waste in Shanghai [J]. Environmental Sanitation Engineering, 2016, 24(6): 18-21(in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-8206.2016.06.006

[22] MCKAY G. Dioxin characterisation, formation and minimisation during municipal solid waste (MSW) incineration: Review [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2002, 86(3): 343-368. doi: 10.1016/S1385-8947(01)00228-5 [23] OOI T C, LU L M. Formation and mitigation of PCDD/Fs in iron ore sintering [J]. Chemosphere, 2011, 85(3): 291-299. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.08.020 [24] ALTARAWNEH M, DLUGOGORSKI B Z, KENNEDY E M, et al. Mechanisms for formation, chlorination, dechlorination and destruction of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/fs) [J]. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 2009, 35(3): 245-274. doi: 10.1016/j.pecs.2008.12.001 [25] ÅMAND L E, KASSMAN H. Decreased PCDD/F formation when co-firing a waste fuel and biomass in a CFB boiler by addition of sulphates or municipal sewage sludge [J]. Waste Management, 2013, 33(8): 1729-1739. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2013.03.022 [26] RYU J Y, MULHOLLAND J A, KIM D H, et al. Homologue and isomer patterns of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans from phenol precursors: Comparison with municipal waste incinerator data [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2005, 39(12): 4398-4406. [27] HELL K, STIEGLITZ L, DINJUS E. Mechanistic aspects of the de-novo synthesis of PCDD/PCDF on model mixtures and MSWI fly ashes using amorphous 12C- and 13C-labeled carbon [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2001, 35(19): 3892-3898. [28] HUANG H, BUEKENS A. On the mechanisms of dioxin formation in combustion processes [J]. Chemosphere, 1995, 31(9): 4099-4117. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(95)80011-9 [29] TUPPURAINEN K, HALONEN I, RUOKOJÄRVI P, et al. Formation of PCDDs and PCDFs in municipal waste incineration and its inhibition mechanisms: A review [J]. Chemosphere, 1998, 36(7): 1493-1511. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(97)10048-0 [30] 陈彤. 垃圾焚烧过程飞灰中二噁英的分布特性及控制技术初步研究[D]. 杭州: 浙江大学, 2003. CHEN T. Preliminary study on the distribution characteristics and control technology of dioxins in fly ash during waste incineration[D]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2003(in Chinese).

[31] ZHOU H, MENG A H, LONG Y Q, et al. A review of dioxin-related substances during municipal solid waste incineration [J]. Waste Management, 2015, 36: 106-118. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2014.11.011 [32] BABUSHOK V I, TSANG W. Gas-phase mechanism for dioxin formation [J]. Chemosphere, 2003, 51(10): 1023-1029. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00716-6 [33] 张梦玫. 典型过渡金属化合物对二恶英异相催化生成影响及作用机理的研究[D]. 杭州: 浙江大学, 2020. ZHANG M M. Research on effect and reaction mechanisms of typical transition metal compounds on heterogeneous catalytic formation of dioxins[D]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2020(in Chinese).

[34] SHAUB W M, TSANG W. Dioxin formation in incinerators [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1983, 17(12): 721-730. [35] BALLSCHMITER K, BRAUNMILLER I, NIEMCZYK R, et al. Reaction pathways for the formation of polychloro-dibenzodioxins (PCDD) and—dibenzofurans (PCDF) in combustion processes: II. Chlorobenzenes and chlorophenols as precursors in the formation of polychloro-dibenzodioxins and—dibenzofurans in flame chemistry [J]. Chemosphere, 1988, 17(5): 995-1005. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(88)90070-7 [36] 杨元平, 杨莉莉, 刘国瑞, 等. 工业热过程中无意产生的持久性有机污染物生成机理 [J]. 中国科学:化学, 2021, 51(4): 401-409. doi: 10.1360/SSC-2020-0148 YANG Y P, YANG L L, LIU G R, et al. Formation mechanism of unintentionally produced persistent organic pollutants in industrial thermal processes [J]. Scientia Sinica Chimica, 2021, 51(4): 401-409(in Chinese). doi: 10.1360/SSC-2020-0148

[37] LI S Q, ZHANG Q Z. Mechanistic studies on the dibenzofuran and dibenzo-p-dioxin formation reactions from o-benzyne precursor [J]. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry, 2015, 1061: 80-88. doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2015.03.006 [38] KHACHATRYAN L, LOMNICKI S, DELLINGER B. An expanded reaction kinetic model of the CuO surface-mediated formation of PCDD/F from pyrolysis of 2-chlorophenol [J]. Chemosphere, 2007, 68(9): 1741-1750. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.03.042 [39] SHIN K J, CHANG Y S. Characterization of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, dibenzofurans, biphenyls, and heavy metals in fly ash produced from Korean municipal solid waste incinerators [J]. Chemosphere, 1999, 38(11): 2655-2666. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(98)00473-1 [40] PANDELOVA M, STANEV I, HENKELMANN B, et al. Correlation of PCDD/F and PCB at combustion experiments using wood and hospital waste. Influence of (NH4)2SO4 as additive on PCDD/F and PCB emissions [J]. Chemosphere, 2009, 75(5): 685-691. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.12.043 [41] LEMIEUX P M, LEE C W, RYAN J V, et al. Bench-scale studies on the simultaneous formation of PCBs and PCDD/Fs from combustion systems [J]. Waste Management, 2001, 21(5): 419-425. doi: 10.1016/S0956-053X(00)00133-1 [42] LIU G R, YANG L L, ZHAN J Y, et al. Concentrations and patterns of polychlorinated biphenyls at different process stages of cement kilns co-processing waste incinerator fly ash [J]. Waste Management, 2016, 58: 280-286. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2016.09.010 [43] BAI S T, CHANG S H, DUH J M, et al. Characterization of PCDD/fs and dioxin-like PCBs emitted from two woodchip boilers in Taiwan [J]. Chemosphere, 2017, 189: 284-290. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.09.080 [44] WEBER R, IINO F, IMAGAWA T, et al. Formation of PCDF, PCDD, PCB, and PCN in de novo synthesis from PAH: Mechanistic aspects and correlation to fluidized bed incinerators [J]. Chemosphere, 2001, 44(6): 1429-1438. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00508-7 [45] SCHOONENBOOM M H, TROMP P C, OLIE K. The formation of coplanar PCBs, PCDDs and PCDFs in a fly ash model system [J]. Chemosphere, 1995, 30(7): 1341-1349. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(95)00038-A [46] PANDELOVA M, LENOIR D, SCHRAMM K W. Correlation between PCDD/F, PCB and PCBz in coal/waste combustion. Influence of various inhibitors [J]. Chemosphere, 2006, 62(7): 1196-1205. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.07.068 [47] HIROTA M, TAKASHITA H, KATO J, et al. Elementary reaction path on polychlorinated biphenyls formation from polychlorinated benzenes in heterogeneous phase using ab initio molecular orbital calculation [J]. Chemosphere, 2003, 50(4): 457-467. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00626-4 [48] MUGICA-ALVAREZ V, SANTIAGO-DE la ROSA N, FIGUEROA-LARA J, et al. Emissions of PAHs derived from sugarcane burning and processing in Chiapas and Morelos México [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2015, 527/528: 474-482. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.04.089 [49] RAVINDRA K, SOKHI R, van GRIEKEN R. Atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source attribution, emission factors and regulation [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2008, 42(13): 2895-2921. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.12.010 [50] 万云洋, 朱迎佳, 费佳佳, 等. 环境中的多环芳烃结构及其危害 [J]. 油气田环境保护, 2017, 27(6): 23-26,56. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-3158.2017.06.006 WAN Y Y, ZHU Y J, FEI J J, et al. The structure of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and its danger in the environment [J]. Environmental Protection of Oil & Gas Fields, 2017, 27(6): 23-26,56(in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-3158.2017.06.006

[51] 秦林波. 医疗垃圾焚烧过程多环芳烃生成与控制研究[D]. 武汉: 武汉科技大学, 2017. QIN L B. The formation and reduction mechanism of PAHs during medical waste incineration[D]. Wuhan: Wuhan University of Science and Technology, 2017(in Chinese).

[52] LIU H M, WANG Y C, ZHAO S L, et al. Review on the current status of the co-combustion technology of organic solid waste (OSW) and coal in China [J]. Energy & Fuels, 2020, 34(12): 15448-15487. [53] MAASIKMETS M, KUPRI H L, TEINEMAA E, et al. Emissions from burning municipal solid waste and wood in domestic heaters [J]. Atmospheric Pollution Research, 2016, 7(3): 438-446. doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2015.10.021 [54] HAN Y, CHEN Y J, FENG Y L, et al. Different formation mechanisms of PAH during wood and coal combustion under different temperatures [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2020, 222: 117084. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.117084 [55] 吕家扬, 林颖, 蔡凤珊, 等. 市政污泥与生活垃圾协同焚烧的二噁英排放特征及毒性当量平衡 [J]. 华南师范大学学报(自然科学版), 2020, 52(5): 31-40. LÜ J Y, LIN Y, CAI F S, et al. PCDD/fs emission and toxic equivalent balance of municipal sewage sludge cocombustion in a solid waste incinerator [J]. Journal of South China Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 2020, 52(5): 31-40(in Chinese).

[56] 陈兆林, 温俊明, 刘朝阳, 等. 市政污泥与生活垃圾混烧技术验证 [J]. 环境工程学报, 2014, 8(1): 324-328. CHEN Z L, WEN J M, LIU C Y, et al. Validity study on co-incineration of municipal sewage sludge and municipal solid waste [J]. Chinese Journal of Environmental Engineering, 2014, 8(1): 324-328(in Chinese).

[57] 余杰, 鱼红霞, 杜义鹏, 等. 城市垃圾焚烧厂直接掺烧城市污泥处置技术及其污染控制 [J]. 环境工程学报, 2020, 14(11): 3155-3161. doi: 10.12030/j.cjee.202001003 YU J, YU H X, DU Y P, et al. Disposal technology and pollution control of directly mixed incineration of municipal sludge in municipal solid waste incineration plant [J]. Chinese Journal of Environmental Engineering, 2020, 14(11): 3155-3161(in Chinese). doi: 10.12030/j.cjee.202001003

[58] 陈海军, 严骁, 许榕发, 等. 市政污泥掺烧对生活垃圾焚烧设施烟气中污染物排放的影响 [J]. 安全与环境学报, 2018, 18(2): 766-772. CHEN H J, YAN X, XU R F, et al. Gaseous pollutant emissions from the mixed combustion of the municipal solid waste incinerator with sewage sludge [J]. Journal of Safety and Environment, 2018, 18(2): 766-772(in Chinese).

[59] EDO M, ORTUÑO N, PERSSON P E, et al. Emissions of toxic pollutants from co-combustion of demolition and construction wood and household waste fuel blends [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 203: 506-513. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.203 [60] SVENSSON MYRIN E, PERSSON P E, JANSSON S. The influence of food waste on dioxin formation during incineration of refuse-derived fuels [J]. Fuel, 2014, 132: 165-169. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2014.04.083 [61] TOMSEJ T, HORAK J, TOMSEJOVA S, et al. The impact of co-combustion of polyethylene plastics and wood in a small residential boiler on emissions of gaseous pollutants, particulate matter, PAHs and 1, 3, 5- triphenylbenzene [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 196: 18-24. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.12.127 [62] CAI P, ZHAN M, MA H, et al. Pollutant emission during co-incineration of landfill material RDF in a lab-scale MSWI fluidized bed furnace [J]. Energy & Fuels, 2020, 34(2): 2346-2354. [63] 李洋洋, 金宜英, 聂永丰. 污泥与煤混烧动力学及常规污染物排放分析 [J]. 中国环境科学, 2014, 34(3): 604-609. LI Y Y, JIN Y Y, NIE Y F. Effects of sewage sludge on coal combustion using thermo-gravimetric kinetic analysis [J]. China Environmental Science, 2014, 34(3): 604-609(in Chinese).

[64] LIN H, MA X Q. Simulation of co-incineration of sewage sludge with municipal solid waste in a grate furnace incinerator [J]. Waste Management, 2012, 32(3): 561-567. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2011.10.032 [65] 严骁, 贾燕, 李淑圆, 等. 污泥掺烧对焚烧后固体废物污染物排放的影响 [J]. 安全与环境学报, 2018, 18(1): 285-291. YAN X, JIA Y, LI S Y, et al. Influence of the municipal solid residue on the municipal solid waste emission [J]. Journal of Safety and Environment, 2018, 18(1): 285-291(in Chinese).

[66] WIKSTRÖM E, RYAN S, TOUATI A, et al. Importance of chlorine speciation on de novo formation of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2003, 37(6): 1108-1113. [67] ALTWICKER E R, KONDURI R K N V, MILLIGAN M S. The role of precursors in formation of polychloro-dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychloro-dibenzofurans during heterogeneous combustion [J]. Chemosphere, 1990, 20(10/11/12): 1935-1944. [68] MORENO A I, FONT R, CONESA J A. Characterization of gaseous emissions and ashes from the combustion of furniture waste [J]. Waste Management, 2016, 58: 299-308. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2016.09.046 [69] CHEN Z L, LIN X Q, LU S Y, et al. Formation pathways of PCDD/Fs during the Co-combustion of municipal solid waste and coal [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 208: 862-870. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.06.044 [70] PRAWISUDHA P, NAMIOKA T, YOSHIKAWA K. Coal alternative fuel production from municipal solid wastes employing hydrothermal treatment [J]. Applied Energy, 2012, 90(1): 298-304. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.03.021 [71] LIN Y S, MA X Q, PENG X W, et al. Hydrothermal carbonization of typical components of municipal solid waste for deriving hydrochars and their combustion behavior [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 243: 539-547. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.117 [72] CHEN W H, KUO P C, LIU S H, et al. Thermal characterization of oil palm fiber and Eucalyptus in torrefaction [J]. Energy, 2014, 71: 40-48. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2014.03.117 [73] TCHAPDA A, PISUPATI S. A review of thermal co-conversion of coal and biomass/waste [J]. Energies, 2014, 7(3): 1098-1148. doi: 10.3390/en7031098 [74] SAEED L, TOHKA A, HAAPALA M, et al. Pyrolysis and combustion of PVC, PVC-wood and PVC-coal mixtures in a two-stage fluidized bed process [J]. Fuel Processing Technology, 2004, 85(14): 1565-1583. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2003.11.045 [75] PENG N N, LI Y, LIU Z G, et al. Emission, distribution and toxicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) during municipal solid waste (MSW) and coal co-combustion [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 565: 1201-1207. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.188 [76] RUOKOJÂRVI P, ASIKAINEN A, RUUSKANEN J, et al. Urea as a PCDD/F inhibitor in municipal waste incineration [J]. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 2001, 51(3): 422-431. [77] CHANG M B, CHENG Y C, CHI K H. Reducing PCDD/F formation by adding sulfur as inhibitor in waste incineration processes [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2006, 366(2/3): 456-465. [78] WU H L, LU S Y, LI X D, et al. Inhibition of PCDD/F by adding sulphur compounds to the feed of a hazardous waste incinerator [J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 86(4): 361-367. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.10.016 [79] SAMARAS P, BLUMENSTOCK M, LENOIR D, et al. PCDD/F prevention by novel inhibitors: addition of inorganic S- and N-compounds in the fuel before combustion [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2000, 34(24): 5092-5096. [80] 翁志华. 固体废物焚烧中二噁英控制措施探讨 [J]. 上海环境科学, 2011, 30(2): 82-84,89. WENG Z H. An approach to dioxin control measures in the process of solid waste incineration [J]. Shanghai Environmental Sciences, 2011, 30(2): 82-84,89(in Chinese).

[81] PANDELOVA M E, LENOIR D, KETTRUP A, et al. Primary measures for reduction of PCDD/F in co-combustion of lignite coal and waste: effect of various inhibitors [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2005, 39(9): 3345-3350. [82] LIU W B, ZHENG M H, ZHANG B, et al. Inhibition of PCDD/Fs formation from dioxin precursors by calcium oxide [J]. Chemosphere, 2005, 60(6): 785-790. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.04.020 [83] LI Q Q, LI L W, SU G J, et al. Synergetic inhibition of PCDD/F formation from pentachlorophenol by mixtures of urea and calcium oxide [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2016, 317: 394-402. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.05.090 [84] MA H T, DU N, LIN X Y, et al. Inhibition of element sulfur and calcium oxide on the formation of PCDD/Fs during co-combustion experiment of municipal solid waste [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 633: 1263-1271. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.282 [85] CHEN Z L, LIN X Q, LU S Y, et al. Suppressing formation pathway of PCDD/Fs by S-N-containing compound in full-scale municipal solid waste incinerators [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2019, 359: 1391-1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.11.039 [86] LUNDIN L, GOMEZ-RICO M F, FORSBERG C, et al. Reduction of PCDD, PCDF and PCB during co-combustion of biomass with waste products from pulp and paper industry [J]. Chemosphere, 2013, 91(6): 797-801. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.090 [87] SHI D Z, MA J Y, WANG H L, et al. Detoxification of PCBs in fly ash from MSW incineration by hydrothermal treatment with composite siliconaluminum additives and seed induction [J]. Fuel Processing Technology, 2019, 195: 106157. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2019.106157 [88] WILKEN M, BÖSKE J, JAGER J, et al. PCDD/F, PCB, chlorobenzene and chlorophenol emissions of a Municipal Solid Waste Incineration plant (MSWI)—variation within a five day routine performance and influence of Mg(OH)2-addition [J]. Chemosphere, 1994, 29(9/10/11): 2039-2050. [89] WEI Y L, LEE J H. Manganese sulfate effect on PAH formation from polystyrene pyrolysis [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 1999, 228(1): 59-66. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00023-6 [90] KAIVOSOJA T, VIRÉN A, TISSARI J, et al. Effects of a catalytic converter on PCDD/F, chlorophenol and PAH emissions in residential wood combustion [J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 88(3): 278-285. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.02.027 [91] CHANG F Y, CHEN J C, WEY M Y. The activity of Rh/Al2O3 and Rh-Na/Al2O3 catalysts for PAHs removal in the waste incineration processes: Effects of particulates, heavy metals, and acid gases [J]. Fuel, 2009, 88(9): 1563-1571. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2009.04.009 [92] 李素梅. 钢铁生产过程中UP-POPs的排放水平和特征研究[D]. 北京: 中国科学院大学, 2015. LI S M. Emission and Characterization of UP-POPs from Steelmaking Processes[D]. Beijing: University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2015(in Chinese).

[93] CHI K H, CHANG S H, HUANG C H, et al. Partitioning and removal of dioxin-like congeners in flue gases treated with activated carbon adsorption [J]. Chemosphere, 2006, 64(9): 1489-1498. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.12.072 [94] LIU W B, TIAN Z Y, LI H F, et al. Mono- to octa-chlorinated PCDD/fs in stack gas from typical waste incinerators and their implications on emission [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(17): 9774-9780. [95] RUEGG H, SIGG A. Dioxin removal in a wet scrubber and dry particulate remover [J]. Chemosphere, 1992, 25(1/2): 143-148. [96] 李元成. 我国典型生活垃圾焚烧烟气中UPOPs催化降解中试研究[D]. 北京: 清华大学, 2016. LI Y C. Pilot test on catalytic destruction of UPOPs in flue gas from typical municipal waste incineratorin China[D]. Beijing: Tsinghua University, 2016(in Chinese).

[97] EL ASSAL Z, OJALA S, PITKÄAHO S, et al. Comparative study on the support properties in the total oxidation of dichloromethane over Pt catalysts [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2017, 313: 1010-1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2016.10.139 [98] KAN J W, DENG L, LI B, et al. Performance of co-doped Mn-Ce catalysts supported on cordierite for low concentration chlorobenzene oxidation [J]. Applied Catalysis A:General, 2017, 530: 21-29. doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2016.11.013 [99] DAI Q G, BAI S X, WANG J W, et al. The effect of TiO2 doping on catalytic performances of Ru/CeO2 catalysts during catalytic combustion of chlorobenzene [J]. Applied Catalysis B:Environmental, 2013, 142/143: 222-233. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.05.026 [100] 蒋威宇. V2O5-WO3/TiO2催化剂协同净化NOx与氯代芳香化合物的反应特征与副产物研究[D]. 杭州: 浙江大学, 2020. JIANG W Y. Reaction characteristics and byproducts analyses over V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalyst in the synergistic elimination of NOx and chloroaromatics[D]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2020(in Chinese).

[101] LILJELIND P, UNSWORTH J, MAASKANT O, et al. Removal of dioxins and related aromatic hydrocarbons from flue gas streams by adsorption and catalytic destruction [J]. Chemosphere, 2001, 42(5/6/7): 615-623. [102] HE F, LUO J Q, LIU S T. Novel metal loaded KIT-6 catalysts and their applications in the catalytic combustion of chlorobenzene [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2016, 294: 362-370. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2016.02.068 [103] 杜翠翠. 球磨法制备钒基催化剂催化降解氯苯及二噁英的基础研究[D]. 杭州: 浙江大学, 2018. DU C C. Fundamental research of catalytic decomposition of chlorobenzenes and dioxins over ball milling synthesized vanadium-based catalysts[D]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2018(in Chinese).

[104] 罗邯予, 铈钛基催化剂上氯苯的催化燃烧性能研究[D]. 北京: 北京化工大学, 2019. . LUO H Y. Ctalytic combustion performance of chlorobenzene over ceria-titania-based complex metal oxides[D]. Beijing: Beijing University of Chemical Technology, 2019(in Chinese).

-

下载:

下载: